22 XRD for Polymer Characterization

scdas

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, students will be able to

- Explain the fundamental principles of X-ray diffraction.

- They can differentiate between WAXD, SAXS, and fiber diffraction techniques and identify key features in an XRD pattern.

- If someone wants a deep understanding, they will be able to calculate structural parameters from XRD data and evaluate polymer orientation and molecular packing.

- Moreover, students will also be able to correlate the property relationship with the polymer processing condition for real-world polymer systems.

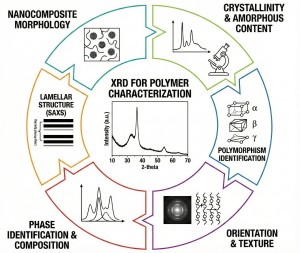

Graphical Abstract:

Figure 1: A visual summary of the applications of X-ray Diffraction (XRD) in Polymer Characterization.

1 Introduction

Understanding the structure of polymers is mandatory for the prediction and optimization of their mechanical, thermal, optical, and barrier properties. Unlike small-molecule crystals, polymers are usually a complex mixture of ordered and disordered regions, which makes their structural characterization uniquely challenging. Among the various analytical techniques available, X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) is considered one of the most powerful and widely used methods for providing insights into the crystalline structure, molecular packing, and orientation of polymer chains. XRD provides direct information on how polymer chains organize into unit cells, how processing influences crystallinity, and how morphology governs material performance1.

In polymer science, XRD helps students and researchers to bridge the gap between molecular arrangement and related behavior. Techniques such as wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD), small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), and fiber diffraction are commonly used to quantify crystallinity, crystallite size, lamellar spacing, and chain alignment. These are common parameters to understand materials ranging from daily usable polyethylene packaging to high-performance fibers, advanced composites, and nanostructured polymer films2.

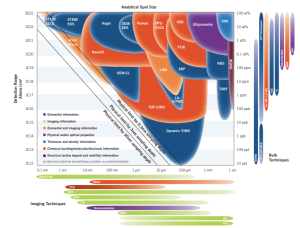

Figure 2: Comparison of XRD with other analytical techniques mapped by detection sensitivity and spatial resolution across materials characterization[Reproduced from3].

Moreover, besides distinguishing crystalline and amorphous regions, XRD also allows researchers to follow how these structural domains change under different processing conditions. Stretching, Heating, cooling, and solvent exposure can significantly change the polymer chain packing, and XRD provides both qualitative and quantitative data for tracking these transformations. For example, changes in peak intensity and width indicate variations in crystallinity and crystallite size, while shifts in peak position indicate modifications in lattice spacing due to thermal expansion, mechanical deformation, or other reasons. As a result, XRD is not only a fundamental structural characterization tool but also a bridge connecting processing strategies to the resulting morphology and functional properties4.

This chapter is focused on guiding students through the fundamental concepts, instrumentation, and practical applications of XRD for polymer characterization. It introduces the basic concept of X-ray interaction with matter, also explains how diffraction patterns are generated, and demonstrates how structural parameters are extracted from real experimental data. At the end, a peer-reviewed research article is included to illustrate how XRD is applied in modern polymer research.

2. Fundamental Principles of XRD

The fundamental principle of XRD is the interaction between X-rays and the periodic arrangement of atomic layers within a material. Because X-rays have wavelengths comparable to interatomic distances, they are scattered (can also say reflected) by electrons in predictable ways. When these scattered waves interact constructively in crystalline regions of a polymer, they generate measurable diffraction peaks. On the other hand, amorphous regions scatter X-rays diffusely and form broad halos. Since most polymers are semi-crystalline, XRD provides a direct method to examine the coexistence of ordered (crystalline) and disordered (amorphous) phases.

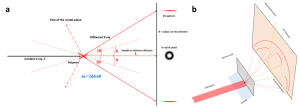

The key relationship for XRD is Bragg’s Law: nλ=2dsinθ

This equation says that diffraction occurs when the path difference between X-rays reflected from parallel lattice planes equals an integer multiple of the wavelength. By analyzing the angles at which diffraction peaks appear, one can calculate the interplanar spacing d. Here, d can help us determine lattice geometry and identify structural changes caused by processing, additives, or thermal history. Overall, the fundamental principles of XRD allow scientists to interpret diffraction patterns and relate them to polymer microstructure, crystallinity, packing, and orientation5.

Figure 3: Schematic illustration of Bragg diffraction geometry and X-ray detection in a typical XRD experiment. (Left figure, basic mechanism of XRD, and right figure, SAXD)

3. Instrumentation and Experimental Setup

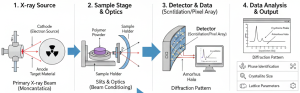

X-ray diffraction (XRD) instrumentation is made to generate X-rays to direct them toward a sample and measure the resulting diffraction pattern with very high precision. The basic components of an XRD machine are an X-ray source, monochromator or filter, goniometer, sample holder, and detector. Let’s discuss the individual components broadly.

Figure 4: Overview of the X-ray diffraction (XRD) workflow for polymer characterization [Photo collected from web].

3.1 X-Ray Source and Beam Conditioning

The X-ray source is usually a sealed tube with a metal target such as copper. Here, copper is widely used for polymer characterization due to its suitable wavelength and strong intensity. Moreover, different filters or monochromators are used to isolate a single wavelength and reduce background noise. It helps in increasing accuracy.

3.2 Goniometer and Diffraction Geometry

It is a machine that controls the angles of the X-ray beam, sample, and detector. The most common configuration is the θ–2θ geometry. In this configuration, the detector moves at twice the angle of the incident beam, and it is ideal for powders, pellets, and bulk polymers. However, for thin films or surface layers, grazing incidence XRD (GIXRD) is used to increase surface sensitivity, which can detect more precisely.

3.3 Sample Preparation for Polymer XRD

Sample preparation effectively influences the data quality of XRD analyses. Polymer materials should be finely ground and evenly spread to reduce preferred orientation. In the case of polymer film, it must be smooth, flat, and free from warping or excessive thickness that could absorb X-rays.

3.4 Detectors and Data Collection

There are several types of detectors used in XRD based on the desired output. Such as: point detectors, 1D silicon strip detectors, or 2D area detectors. The 2D detectors are especially valuable for polymers because they capture anisotropic scattering patterns from oriented samples. The combined 1D and 2d detector signals give a broad idea of the crystal lattice.

4. Data Interpretation and Analysis Techniques

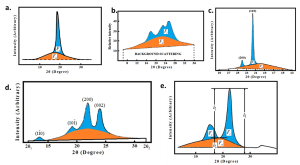

Data interpretation in XRD is essential for transforming diffraction patterns into meaningful structural information of polymers. Most polymers contain both crystalline and amorphous regions; thus, their XRD patterns consist of both sharp Bragg peaks superimposed on a broad amorphous halo. There are dozens of methods that have been developed throughout the year to analyze XRD data2. To analyze the peaks, we need to follow some steps.

The first step in analysis is identifying peak positions (2θ), from which we can get the specific lattice plane spacing. By calculating interplanar spacing d, we can determine changes in chain packing caused by processing, temperature, or chemical modification. Moreover, the Peak intensity provides knowledge into the degree of order and relative abundance of specific crystal planes.

Figure 5: Sharp crystalline peak and amorphous halo. [Photo reproduced and merged from: a. The XRD pattern of the PTFE (Teflon®) resin was analyzed using with method of 6; b. The XRD pattern of the PET sample was analyzed using with method of 7; c. The XRD pattern of a linear PE sample (M =7×106 g/mol, ρ=0.9309 g/cm3) at room temperature was analyzed using with method of 8; d. The XRD pattern of a highly tempered, maximally crystallized polyurethane sample was analyzed using with method of 9; e. The XRD pattern of a cellulose I sample was analyzed using with method of 10;]

Figure 5: Sharp crystalline peak and amorphous halo. [Photo reproduced and merged from: a. The XRD pattern of the PTFE (Teflon®) resin was analyzed using with method of 6; b. The XRD pattern of the PET sample was analyzed using with method of 7; c. The XRD pattern of a linear PE sample (M =7×106 g/mol, ρ=0.9309 g/cm3) at room temperature was analyzed using with method of 8; d. The XRD pattern of a highly tempered, maximally crystallized polyurethane sample was analyzed using with method of 9; e. The XRD pattern of a cellulose I sample was analyzed using with method of 10;]

The amorphous halo suggests the presence of disordered chain segments. By separating the crystalline peaks from the amorphous background, we can get the degree of crystallinity. This value is critical because it correlates strongly with mechanical properties, thermal stability, and barrier performance. Moreover, peak broadening is another important feature where the narrow peaks indicate well-ordered and larger crystallites, while broader peaks mean smaller crystallite domains or increased structural disorder. We can use the Scherrer equation to estimate crystallite size:

D=Kλ/βcosθ

where D is crystallite size, β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM), λ is the X-ray wavelength, and K is a shape factor.

Furthermore, the intensity distribution around the diffraction ring (also called azimuth angle) contains information about molecular orientation. Azimuthal integration and tools like Herman’s Orientation Function quantify the degree of chain alignment, which is essential in understanding the performance of high-strength or highly processed materials. In these ways, we can get a comprehensive assessment of polymer microstructure, linking diffraction features to crystallinity, orientation, and morphological changes4.

5. Quantifying Polymer Structural Parameters in XRD

To quantify the structural parameters in semi-crystalline polymers, the researchers analyze the diffraction pattern of the XRD peaks. From the pattern, they can obtain key information such as crystallinity, crystallite size, lattice spacing, molecular orientation, and lamellar structure. These parameters are directly related to the mechanical, thermal, and processing behavior of polymeric materials.

5.1 Degree of Crystallinity

The degree of crystallinity gives an idea of the ordered regions within a polymer. Here, the ratio of crystalline peak area to the total scattering area provides an estimate of percent crystallinity. This value is crucial because crystallinity affects stiffness, melting temperature, barrier properties, and dimensional stability.

5.2 Crystallite Size

Crystallite size is another important parameter that reflects the average dimensions of ordered polymer domains. By using the Scherrer equation, which relates the full width at half maximum (FWHM) to the size of the crystalline domains, we can determine the crystallite size. Here, the narrow peaks indicate larger, well-ordered crystallites, while broader peaks suggest smaller or less perfect domains.

5.3 Lattice Spacing and Unit Cell Parameters

The positions of diffraction peaks provide information about lattice spacing (d-spacing) according to Bragg’s Law. From these values, researchers can determine the polymer’s unit cell type and calculate lattice constants. Shifts in peak position reveal changes in chain packing that may result from copolymerization, thermal expansion, or molecular alignment.

5.4 Molecular Orientation

The anisotropic diffraction patterns in XRD reflect the alignment of polymer chains. By examining the azimuthal distribution of scattered intensity, XRD quantifies molecular orientation and provides values such as Herman’s Orientation Function.

6. Applications of XRD in Polymer Science

X-ray diffraction is widely used in polymer science to characterize different intrinsic properties of polymers. Because polymers vary greatly in morphology, XRD offers versatile applications across fibers, films, composites, blends, and recycled materials. Some of the common application areas are: determining the crystallinity in polymers, which helps correlate crystallinity with mechanical strength, melting behavior, stiffness, and barrier properties. It is used to study polymer blends, composites, and nanocomposites. Moreover, it can be used to analyze structural changes during thermal processing, allowing in situ observation of crystallization, melting, and annealing by tracking peak intensity, width, and position changes with temperature. Researchers also use XRD to compare virgin and recycled polymers, revealing differences that arise due to thermal degradation, multiple processing cycles, or contamination in recycled materials. Furthermore, they also use it for filler dispersion and phase morphology in composite systems, detecting crystalline reinforcement phases (e.g., talc, clay, graphene), their alignment under processing, and the effect of fillers on polymer crystallinity12.

If we want to classify the application area, then we can classify it as:

- Pharmaceutical Industry;

- Microelectronics Industry;

- Energy Applications;

- Corrosion Analysis;

- Glass Industry;

- Forensic Science;

- Geological Applications;

- Construction Applications;

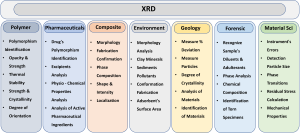

Figure 6: Applications of X-ray diffraction (XRD) across major scientific and industrial fields.

7. Case Study: Discussion of Selected Peer-Reviewed Paper

The review paper entitled: Small-Angle X-ray Scattering of Polymers by Chu and Hsiao provides a comprehensive and basic description of how SAXS and other similar X-ray scattering techniques are used to study polymer morphology over large length scales. The WAXD, which examines atomic-scale ordering, is different from SAXS, which gives an idea of the hierarchical structures. This review is especially relevant to this chapter because it demonstrates how XRD-based scattering methods complement the techniques discussed in this chapter, offering both nanoscale crystallographic information (WAXD) and mesoscale structural insight (SAXS)10.

7.1 Overview of the Study

The authors described that SAXS measures scattering at very small angles to get an idea of structures from ~1 to 1000 nm. The introduction of the paper clearly supports that SAXS captures scattering from large lattice spacings, amorphous regions, and mesomorphic structures. The review also discusses the evolution of SAXS technology, which highlights the improvements in X-ray sources, synchrotron radiation, and detector systems. The development now allows time-resolved and in situ analysis of polymer crystallization, deformation, fiber spinning, and flow behavior10.

7.2 X-ray Methods Used in the Review

The paper gives detailed descriptions of instrumentation, including synchrotron SAXS beamlines, Bonse–Hart optics, pinhole collimation, Kratky cameras, and advanced CCD area detectors.

The paper also describes different environmental control systems, such as temperature chambers, pressure cells, shear stages, and fiber-spinning setups, for time-resolved and in-situ structural measurements. Moreover, the review emphasizes a combined SAXS/WAXD instrumentation, where simultaneous measurements allow researchers to follow phase transitions (crystallization, melting), deformation, and morphological evolution across multiple length scales.

7.3 Key Findings and Structural Insights

A central idea of the paper is how SAXS patterns arise and how they can be expressed through the scattering vector, intensity distribution, and real-space correlation functions. The authors clearly state that the differences in electron density between domains control the scattering intensity, which gives SAXS sensitivity to lamellar stacking in semicrystalline polymers. This method is particularly important in materials such as polyethylene or PET. The paper also illustrates how lamellar periodicity can be precisely quantified directly from the position of SAXS maxima, and how the Fourier transformation of the scattering curve indicates layer thicknesses and interfacial widths.

In my opinion, what makes this paper particularly valuable is the authors’ attention to realistic samples where peaks are broad or overlapping; they demonstrate how the correlation-function approach provides reliable structural information even when idealized scattering patterns are not present.

Another strength of the article is its consideration of SAXS as a dynamic tool. The authors describe time-resolved experiments, especially those conducted during polymer crystallization, drawing, or thermal treatment. This strongly superimposes with current theoretical frameworks, such as Avrami crystallization kinetics. As crystallites grow or reorganize the crystal lattice, SAXS patterns change accordingly, revealing not only the rate of crystallization but also how lamellae thicken, thin, or reorient. The paper also emphasizes the significance of two-dimensional SAXS for studying oriented polymers, such as fibers, films, and drawn specimens. This dimension of the paper points out that SAXS is not only a tool for static morphology but also for understanding how processing pathways shape microstructure.

7.4 Connection to This Chapter

This article has substantial relevance to this chapter because it extends the principles of X-ray diffraction introduced earlier and demonstrates how SAXS complements WAXD in characterizing polymer structure. Although this chapter focuses on how WAXD reveals atomic-level ordering, crystallinity, lattice spacing, and molecular orientation, the paper shows that SAXS provides access to much larger structural features such as lamellar spacing, electron-density fluctuations, and hierarchical morphology. The article also reinforces the chapter’s emphasis on structure processing relationships. Earlier sections describe how XRD tracks changes during crystallization, melting, or mechanical deformation; the paper extends this idea by illustrating time-resolved SAXS measurements that follow the evolution of lamellar stacks and structural rearrangements during processing. In this way, the review combines the theoretical understanding and practical research applications, helping students and researchers appreciate how combined WAXD–SAXS techniques provide a comprehensive picture of polymer morphology and its development.

8. Conclusion

X-ray diffraction is still one of the most powerful and versatile techniques for understanding the structural complexity of polymeric materials. Throughout this chapter, the principles of X-ray interaction with polymer crystal, the interpretation of diffraction patterns, and the quantification of key structural parameters have been connected. By examining both crystalline and amorphous domains, XRD enables researchers to show how polymer chains pack, orient, and reorganize under different processing conditions. Different modern developments of XRD, such as SAXS, WAXD, fiber diffraction, and grazing-incidence methods, provide complementary sample-specific data. Ultimately, XRD not only reveals how polymers are organized but also how they evolve during fabrication, processing, and use. A strong foundation in XRD, therefore, equips students and researchers with essential tools for advancing polymer science and for designing materials with tailored structural and functional properties.

9. References

- Widjonarko, N. E. Introduction to Advanced X-ray Diffraction Techniques for Polymeric Thin Films. 1–17 (2016) doi:10.3390/coatings6040054.

- Uzun, İ. Methods of determining the degree of crystallinity of polymers with X ‑ ray diffraction : a review. (2023). doi:10.1007/s10965-023-03744-0.

- EAG Laboratories. Analytical and Materials Characterization Techniques. EAG Laboratories Technical Resource, 2024. Accessed at: https://www.eag.com/techniques/

- Omori, N. E. et al. Recent developments in X-ray diffraction / scattering computed tomography for materials science Subject Areas : Authors for correspondence : (2025) doi:10.1098/rsta.2022.0350/249912/rsta.2022.0350.pdf.

- Can J Chem Eng – 2020 – Khan – Experimental methods in chemical engineering X‐ray diffraction spectroscopy XRD.pdf.

- Ryland, A. D. A. L. No Title.

- Johnson, E. X-Ray Diffraction Studies of the Crystallinity in Polyethylene Terephthalate. 11, 205–209 (1959).

- Polyethylene, L. & Diffraction, F. W. X. DEGREE O F CRYSTALLINITY O F LINEAR POLYETHYLENE. 5, 925–929 (1967).

- Kettenl, B. & Prof, H. Ich mSchte noch die Bemerkungen der Herren Prof. 25–31.

- Tanaka, F. & Koshijima, T. Science and Technology Degree of Polymerization Wood meal was delignified according to Klauditz ( 1957 ). It was nitrated by the method. 265–273 (1981).

- Bunaciu, A. A. et al. Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry X-Ray Diffraction : Instrumentation and Applications X-Ray Diffraction : Instrumentation and Applications. 8347, (2015).

- Murthy, N. S. Recent developments in polymer characterization using X-ray diffraction RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN POLYMER CHARACTERIZATION USING X-RAY DIFFRACTION. (2014).