11 Industrial Composting of Plastics and Polymers

Jess Rugeley

Introduction

Upon completion of this chapter, students will be able to:

- Define industrial composting and distinguish it from home composting.

- Explain the chemical and biological mechanisms by which polymers biodegrade under industrial composting conditions.

- Describe how composting conditions influence biodegradation, including temperature, aeration, humidity, pH, and microbial diversity.

- Interpret standardized test methods for assessing polymer compostability, including CO2 evolution and % biodegradability.

- Identify common misconceptions about compostable plastics and describe real world challenges with composting methods.

- Explain the environmental and economic motivations for compostable polymers within a circular economy framework.

An increase in plastic waste accumulation poses a major environmental crisis. The durability of plastics, such as polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET), resist degradation for decades to centuries. Current end of life management strategies, such as landfilling and incineration, often produce undesirable byproducts.1 These challenges have driven global interest in developing alternative polymers designed to break down more readily under controlled environmental conditions, such as industrial composting. Composting offers a more sustainable alternative for managing biodegradable plastic waste, supporting a transition towards a more circular economy. Composting is beneficial towards the environment through soil productivity and acting as a nutrient rich fertilizer. Economically, composting helps reduce the reliance on landfills and generate new job opportunities. Lastly, industrial composting serves as an important tool for research and development sectors to evaluate how their polymer innovations compare in sustainability to existing materials, working towards a more sustainable future.

Industrial composting is characterized by a highly regulated environment with elevated temperatures, continuous aeration, high moisture levels, and active microorganisms.1 These characteristics facilitate the biodegradation of organic materials into carbon dioxide, water, and biomass. Unlike home composting or natural soil environments, industrial composting typically uses thermophilic temperatures around 55 to 60°C and maintains optimized oxygen and humidity levels.2 These conditions work towards accelerating the degradation of certain polymers, especially those that readily biodegrade, such as biopolymers like polylactic acid (PLA) or polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs). These factors govern the kinetics of biodegradation. To standardize the evaluation of compostable plastics, international test methods (ISO, ASTM etc.) quantify biodegradation through CO2 evolution and assess physical degradation under controlled laboratory conditions.

Despite clear environmental and economic benefits, the industrial use of these materials face real world challenges and is subject to common misconceptions. Waste streams are frequently contaminated with non-compostable materials. Further, it is a common misconception that all bio-based materials are inherently biodegradable. However, biodegradability should not be assumed, and some polymers that are compostable in an industrial environment may fail to break down in home composting environments, leading to pollution issues.

Together, this chapter introduces the science and practice of industrial composting of polymers, exploring the fundamental mechanisms and the practical challenges associated with compostable plastics in real waste management systems.

Core Principles of Industrial Composting

Industrial composting is an aerobic biological oxidation process typically facilitated through methods of windrows or in-vessel systems.2 Microorganisms break down organic compounds, releasing carbon dioxide, water, biomass, and residue as byproducts, a schematic of a basic biodegradation process is shown in Figure 1. Unlike home composting, industrial composting maintains tightly controlled conditions, enabling rapid transformations that may not naturally occur in typical soil or landfill environments.

Figure 1. Schematic of a typical biodegradation reaction of a polymer with factors that can influence the biodegradation process and resulting products.

A defining characteristic of industrial composting is the use of thermophilic temperatures during the degradation process. Temperatures will typically reach 55 to 60°C, maintained by the system design including forced aeration, mechanical mixing, and moisture management. Thermophilic microorganisms will thrive at these higher temperatures, ultimately accelerating the breakdown of natural materials and engineered biopolymers. Many biodegradable polymers, such as PLA, degrade very slowly at room temperature but break down rapidly when exposed to the heat and moisture levels typical of industrial compost systems.3 Thus, the composting system functions as an accelerated environment for chemical and biological reactions that might otherwise take years.

In addition to temperature, there are other factors that can affect the biodegradation process. Such as, aeration and moisture where conditions must be aerobic and oxygen levels should not drop below 6% and moisture levels should be maintained at 50%.4 The rate of degradation is fundamentally limited by the chemical and physical characteristics of the polymer sample. For example, low molecular weight fragments and amorphous regions in semi-crystalline polymers are consumed faster since they are more accessible to water and enzymes.5 It is also influenced by the physical form of the polymer sample, whether it is a powder or film, and specific surface area of the test material.6 A video attached below establishes how industrial composting works on a broader scale rather than in a laboratory space.

Environmental Factors Controlling Biodegradation Rates

The rate at which a polymer biodegrades in an industrial composting environment depends on the interaction between polymer morphology and the environmental conditions. Understanding these factors is essential for interpreting biodegradation results, predicting real world performance, and designing polymers that are compatible with composting infrastructures.

As mentioned previously, temperature is the most influential factor. As temperature increases and reaches thermophilic conditions, it also increases hydrolysis rates, polymer chain mobility, and microbial enzymatic activity. For example, PLA often shows minimal biodegradation at 25 °C but degrades significantly within weeks at 58 °C, showcasing how industrial composting is a more effective waste management route for PLA than home composting.3

Since industrial composting is aerobic, the presence of oxygen supports oxidative metabolism. Forced aeration is often done through blowers or passive air diffusion through porous substrates to ensure aerobic conditions. Insufficient oxygen reduces carbon dioxide evolution and can compromise the quality of the compost being used.1,2

Lastly, the pH of compost can influence enzyme activity and hydrolysis rates. Acidic conditions may accelerate hydrolysis while later neutral conditions could support microbial growth. Polymers that release acidic degradation products, like PLA, could alter the pH of the compost. Furthermore, having a diverse microbial community can increase the existence of the organisms consuming a particular polymer fragment. Fungi often dominate initial decomposition, while bacteria accelerate decomposition during later phases.7

Standardization for Lab Scale Assessments

Standardization of testing is crucial for providing consistency and reliability in comparing materials. International test methods determine the ultimate biodegradability and the rate of degradation through laboratory conditions. There are many available standards, but to focus on a few, ASTM D5338 and ISO 14855-1 focuses on controlled composting while methods like ASTM D5988 and ISO 17556 is used for aerobic biodegradation in soil at lower, mesophilic temperatures.

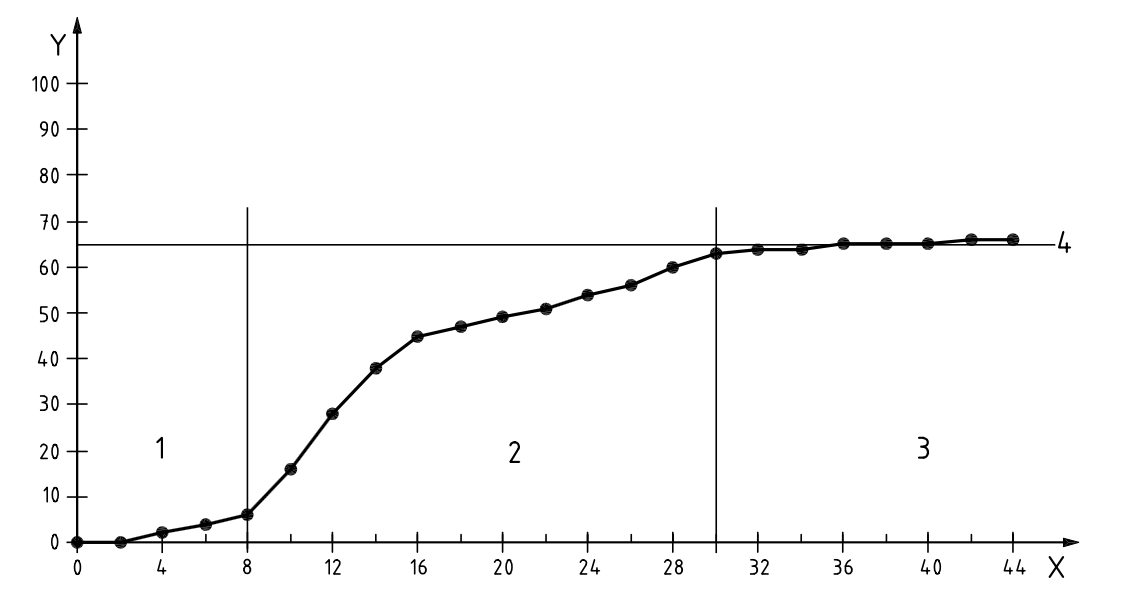

When completing laboratory scale experiments, standards such as ISO 14855-1 and ASTM D5338 focus on measuring carbon dioxide evolution as polymers biodegrade under controlled thermophilic composting conditions. These types of tests compare the measured evolved carbon dioxide from the test polymer to the theoretical maximum carbon dioxide determined by elemental carbon content. Carbon dioxide can be discontinuously measured through carbon dioxide traps in a basic solution such as KOH, NaOH, or Ba(OH)2, and quantified via acid-base titration.8 It can also be measured continuously through direct sensors. Depending on the standard, a material can be considered aerobically biodegradable if it reaches a certain % biodegradability after a given time period. An example of the data typically achieved through these methods is shown in Figure 2 below. To highlight, typical biodegradation curves have three distinct phases: the lag phase, degradation phase, and plateau phase. The lag phase is measured from the start of a test until biodegradation has increased to about 10% of the maximum level of biodegradation.4 The degradation phase starts from the end of the lag phase until about 90% of the maximum level of biodegradation. Lastly, the plateau phase starts from the end of the biodegradation phase to the end of the overall test. Further, complementary analytical techniques can be implemented to provide mechanistic insight by tracking material changes. Such as, size exclusion chromatography to monitor the reduction in molecular weight due to bond cleavage, FTIR to detect changes in chemical bonds and functional groups, or SEM for surface morphology detection.

Figure 2. Example of a biodegradation curve where the x-axis is time (days) and the y-axis is the degree of biodegradation (%). The lag phase is represented in section 1, degradation phase in section 2, and plateau phase in section 3. 4 is the mean degree of biodegradation at 65%. The graph was adapted from ISO-14855-1.4

Real World Challenges

Landfills act as reservoirs for microplastics, small particles, and fibers. These fragments originate from the deterioration of polymers and can be transported into the surrounding ecosystems by air and leachate.9 There is a persistence of microplastics in the environment that cause a public health threat. They accumulate contaminants and can be ingested by wildlife. Furthermore, landfills are reaching maximum capacity at a rapid rate, and often release toxic byproducts, contributing to environmental pollution. Therefore, understanding the biodegradation characteristics of plastics is important. On another hand, incineration and recycling have drawbacks as well. Incineration releases toxic airborne particulates, including volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that are carcinogenic and harmful to health.10 Recycling processes often suffer from contamination and result in plastics losing the needed mechanical properties required for reuse, leading to eventual disposal.11

Real world composting environments may experience temperature fluctuations, have lower moisture content than laboratory reactors, include feedstock contamination, lack the microbial community needed to fully degrade some polymers, and produce microplastic residues from partially degraded materials. However, the primary challenge for polymers being studied in lab spaces lies in high resource demands and inconsistencies.

Additionally, there is a major misconception that materials labeled as biodegradable or compostable automatically disappear in any environment. As mentioned previously, PLA is known to break down successfully in controlled industrial composting environments that use thermophilic temperatures.12 However, these same polymers may fail to degrade adequately or take years to decompose in natural environments that may have cooler temperatures. Thus, there is a clear limitation to their widespread use and environmental benefit.

Article Summary

Fogašová et al. investigated the development and performance of bioplastic blends designed to achieve full biodegradation across different composting environments.13 The primary objective of their study was to develop ready to use materials based on blends of PLA and PHB that possess suitable properties for wide application while ensuring complete biodegradation. PLA is a widely available biobased polymer, but it is known to not biodegrade under home composting conditions, needing temperatures above its glass transition temperature to degrade. However, PHB biodegrades easily, even under mild conditions, but lacks sufficient processing and mechanical properties for many applications on its own.

These researchers formed PLA/PHB blends, some including thermoplastic starch as a filler to reduce cost, along with citric acid ester based plasticizers. These blends were processed into various real world product forms such as cups, thermoforming sheets, and bags, and tested for compostability. They had three main testing environments to evaluate biodegradability. The first was laboratory tests using an adapted ISO 14855-1 method, measuring carbon dioxide production in mature municipal compost at both thermophilic and mesophilic temperatures. The second method was through an electric composter where samples were incubated with kitchen waste at higher operating temperatures, 65 to 75 °C, to assess weight loss. The last method was through a municipal composting plant where the tests were conducted under real world industrial composting conditions in two independent 12 week cycles. An example of the setup is shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. The compost pile and plastic net with cut samples from Fogašová et al.13

The researchers found that the PLA/PHB blends proved to fully biodegrade under industrial composting conditions, achieving 100% mineralization in approximately 90 days. Further tests were conducted with SEM for surface analysis, confirming strong surface erosion. GPC was also conducted where the researchers observed that disintegration and mineralization occurred in parallel. Thus, these PLA/PHB blended materials do not leave microplastics in the environment after industrial composting. Lastly, the results shown with the home composting test exhibited 100% mineralization after 180 days, even those with higher proportions of PLA and being under mild temperature conditions.

These results contradict the conventional understanding that PLA cannot biodegrade effectively below its glass transition temperature. The researchers propose that the success is due to the hot melt blending process, which induces a re-esterification reaction between the PLA and PHB. This process forms PLA/PHB co-polyesters where the easily biodegradable PHB segment promotes the scission of the polymer chains, ultimately leading to the complete biodegradation of the material under mild, mesophilic temperatures. This paper provides proof of concept for a blended polymer system that meets high standards of industrial composting while providing the necessary process robustness to succeed in real world municipal composting environments.

Test Your Knowledge

References

- Farhidi, F.; Madani, K.; Crichton, R. How the US Economy and Environment can Both Benefit From Composting Management. Sage Journals. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/11786302221128454.

- Team Compost Connect. What is Industrial Composting. Compost Connect (2024). https://www.compostconnect.org/what-is-industrial-composting/.

- paper

- ISO 14855-1:2012. ISO. https://www.iso.org/standard/57902.html.

- Chamas, A.; Moon, H.; Zheng, J.; Qiu, Y.; Tabassum, T.; Jang, J. H.; Abu-Omar, M.; Scott, S. L.; Suh, S. Degradation Rates of Plastics in the Environment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8 (9), 3494–3511.

- ISO 17556:2019. ISO. https://www.iso.org/standard/74993.html.

- Insam, H., de Bertoldi, M., 2007. Microbiology of the composting process. Compost. Sci. Technol. Waste Manage. Ser. 8, 25-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1478-7482(07)80006-6.

- D5338-15(2021) Standard Test Method for Determining Aerobic Biodegradation of Plastic Materials Under Controlled Composting Conditions, Incorporating Thermophilic Temperatures. https://store.astm.org/d5338-15r21.html.

- Wojnowska-Baryła, I.; Bernat, K.; Zaborowska, M. Plastic Waste Degradation in Landfill Conditions: The Problem with Microplastics, and Their Direct and Indirect Environmental Effects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19 (20), 13223. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013223.

- Verma, R.; Vinoda, K. S.; Papireddy, M.; Gowda, A. N. S. Toxic Pollutants from Plastic Waste- A Review. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 35, 701–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2016.07.069.

- Abdelmoez, W., Dahab, I., Ragab, E.M., Abdelsalam, O.A., Mustafa, A. Bio- and oxo-degradable plastics: Insights on facts and challenges . Polym. Adv. Technol., 32, 1981, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/pat.5253.

- Karamanlioglu, M., Robson, G. The influence of biotic and abiotic factors on the rate of degradation of poly(lactic) acid (PLA) coupons buried in compost and soil. Polymer Degradation and Stability, Volume 98, Issue 10, 2013, Pages 2063-2071, ISSN 0141-3910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2013.07.004.

- Fogašová M, Figalla S, Danišová L, Medlenová E, Hlaváčiková S, Vanovčanová Z, Omaníková L, Baco A, Horváth V, Mikolajová M, Feranc J, Bočkaj J, Plavec R, Alexy P, Repiská M, Přikryl R, Kontárová S, Báreková A, Sláviková M, Koutný M, Fayyazbakhsh A, Kadlečková M. PLA/PHB-Based Materials Fully Biodegradable under Both Industrial and Home-Composting Conditions. Polymers (Basel). 2022 Sep 30;14(19):4113. doi: 10.3390/polym14194113. PMID: 36236060; PMCID: PMC9572414.