36 Why Polystyrene Is Brittle, but PMMA Is Tougher: Structure–Property Relationships

How Molecular Structure Controls Mobility, Crazing, and Toughness in Glassy Polymers

Merin Jahan Sabiha

- Introduction

Polystyrene and poly (methyl methacrylate) are two of the most common amorphous polymers. Both are transparent, both are processed as thermoplastics, and both sit above room temperature in their glassy state. Yet their mechanical behavior could not be more different. Polystyrene (PS) snaps with almost no warning, while PMMA deforms in a controlled way, resists crack growth, and absorbs more energy before failure.

This contrast is not a processing artifact. It comes directly from molecular structure: how side groups restrict mobility, how free volume evolves near the glass transition, how chains entangle, and which microscopic processes like crazing or shear yielding activate when the material is stressed.

This chapter introduces the molecular principles that control brittleness and toughness in glassy polymers and uses the PS–PMMA pair as a teaching example. Students will link chemical structure to mobility, mobility to deformation mechanisms, and deformation mechanisms to macroscopic performance. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the classic Donald & Kramer (1982) paper, which showed how crazing and shear compete in glassy polymers and why PS fails earlier than PMMA.

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, students will be able to:

- Explain the molecular basis of the glass transition and segmental mobility.

- Describe how side-group structure and chain stiffness affect polymer toughness.

- Distinguish between crazing and shear yielding as deformation mechanisms.

- Compare PS and PMMA using entanglement density, mobility, and failure modes.

- Interpret the microscopy evidence of craze initiation and tip blunting from Donald & Kramer (1982).

- Key Concepts

2.1 The Glass Transition and Segmental Mobility

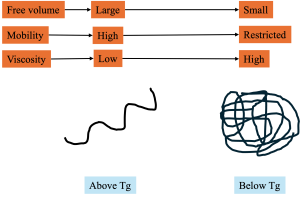

The glass transition marks the temperature range where polymer chains lose the ability to undergo coordinated segmental motion. Below Tg, segments are effectively trapped within their local free-volume cages, and the polymer behaves as a brittle glass. Above Tg, segments gain enough thermal energy to overcome rotational barriers, resulting in rubbery or leathery behavior. Although Tg is easy to measure experimentally, its molecular basis is complex.

The loss of segmental mobility is tied to the collapse of excess free volume, the portion that enables cooperative rearrangements during cooling(White & Lipson, 2016). Polymers with bulky or rigid side groups require more thermal energy to activate these modes, leading to higher Tg values and lower mobility (Xie et al., 2020). Thin-film studies further demonstrate that interfacial constraints can suppress mobility, producing Tg shifts that arise from mobility gradients across the film thickness (Fryer et al., 2001). This relationship is summarized in Figure 1, which illustrates how free-volume contraction near Tg restricts segmental mobility and transforms the polymer from a rubbery to a glassy state.

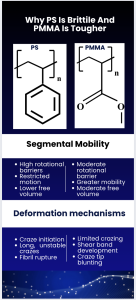

2.2 Chain Flexibility and Side-Group Structure

Side groups determine how freely a backbone can rotate. PS contains a large aromatic phenyl ring on every repeat unit. This rigid, bulky group restricts rotation and creates a stiff local environment. PMMA also contains a sizeable side group (the COOCH₃ ester), but it is less rigid and more polar, allowing somewhat greater mobility.

Polystyrene (PS):

- Contains a bulky phenyl ring directly attached to the backbone

- The phenyl ring introduces steric hindrance

- Backbone rotations require more energy → restricted segmental motion

- Consequence: higher stiffness, limited energy dissipation, brittle fracture

PMMA:

- Contains a polar ester group that is smaller than phenyl

- Allows slightly more rotational freedom

- The ester group interacts through dipole forces, which stabilize crazes

- Consequence: higher work of fracture, controlled deformation

2.3 Free Volume: Total vs Excess

Free volume is not a single quantity. It has multiple physically meaningful components (White & Lipson, 2016):

- Hard-core volume (Vhc): volume occupied by the chain segments themselves

- Vibrational free volume (Vfree:vib): small, T-dependent space associated with vibrational motion

- Excess free volume (Vfree:exs): the additional volume that allows segmental rearrangement

Only excess free volume directly correlates with mobility and Tg. When excess free volume collapses, the polymer behaves like a glass.

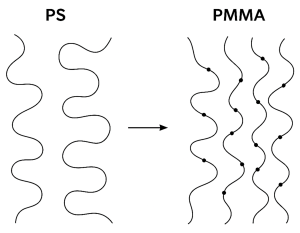

2.4 Entanglement Density and Chain Topology

Regardless of Tg, the ability of a polymer to deform without fracturing depends heavily on entanglements. That means the physical topological constraints between chains. Entanglement density strongly influences whether deformation localizes into crazes or redistributes by shear yielding (Narayan & Anand, 2021).

PS:

- Lower entanglement density due to a rigid backbone

- Crazes form readily, grow unstably, and lead to brittle failure

PMMA:

- Moderately higher entanglement density

- Supports stable craze formation and transition to shear deformation

- Allows absorption of more energy before fracture

Figure 2 visualizes how differences in entanglement spacing between PS and PMMA influence whether a polymer crazes or shear-yields under stress.

2.5 Crazing vs Shear Yielding

Crazing and shear yielding are the two dominant deformation pathways in glassy polymers.

Crazing:

- Appears as a network of fibrils and voids

- Occurs in glassy polymers with limited segmental mobility

- PS → large craze zones → sudden catastrophic failure

Shear yielding:

- Occurs through localized plastic flow

- Requires moderate mobility and sufficient entanglement

- PMMA → yields gradually → greater toughness

TEM studies show that many craze tips are blunted by localized shear, preventing runaway growth (Donald & Kramer, 1982). PS lacks sufficient mobility to activate this stabilizing mechanism. PMMA can activate limited shear, improving toughness. Modern nanoscale toughening studies confirm that enhancing local mobility can convert unstable crazing into more ductile flow (Razavi et al., 2020).

- Why PS Is Brittle, and PMMA Is Tough

Despite similar vinyl backbones and glass-transition temperatures (PS ~100 °C; PMMA ~105 °C), their side groups create very different mobility and fracture profiles. Structural differences in side groups control mobility below Tg. This modest mobility difference determines whether deformation localizes catastrophically (PS) or redistributes through shear (PMMA).

Entanglement density amplifies the contrast. PS’s rigid backbone yields sparse entanglements, so crazes grow unstably and lead directly to brittle fracture with very low elongation at break (~3–4%) (Narayan & Anand, 2021). PMMA, with slightly higher entanglement density and moderate mobility, forms crazes that remain stable long enough for shear bands to develop. This mixed craze–shear mechanism increases toughness, reflected in its higher elongation at break (~5–10%) and greater work of fracture.

| Property | Polystyrene (PS) | PMMA |

| Side group | Rigid phenyl | Less bulky ester |

| Tg | ~100 °C | ~105 °C |

| Mobility below Tg | Very low | Moderate |

| Entanglement density | Low | Moderate |

| Deformation mode | Crazing → brittle fracture | Crazing + shear yielding |

| Elongation at break | ~3–4% | ~5–10% |

| Modulus | High | Slightly lower |

| Toughness | Low | Higher |

Structure → Mobility → Deformation → Toughness pathway:

PS: bulky phenyl → restricted mobility → sparse entanglements → unstable crazes → brittle.

PMMA: ester group → moderate mobility → higher entanglements → stable crazes + shear → tougher.

This compact structure–property chain explains why two polymers with similar Tg values behave so differently in real mechanical loading.

- Discussion of Peer-Reviewed Study: (Donald & Kramer, 1982)

The Donald & Kramer study does not examine PMMA directly, but it establishes the mechanistic framework needed to interpret why different glassy polymers-such as PS and PMMA-show contrasting toughness. Their thin-film TEM experiments reveal how crazing and shear compete during deformation, and how this competition depends on chain mobility and entanglement spacing.

4.1 Experimental Insight

Using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Donald & Kramer examined strained films of polymers that span the range between PS-like and PC-like behavior. Two central observations emerged:

- Craze tips often become blunted by shear deformation.

As stress concentrates at a craze tip, a localized shear zone may form and relax the stress field. This blunting prevents further craze advance, producing short, “cigar-shaped” crazes instead of long, unstable ones.

- The balance between shear and crazing is structure-dependent.

Polymers with higher mobility or greater entanglement density show more shear near craze tips, which stabilizes deformation. Polymers with rigid side groups or low mobility-such as PS-show little shear relaxation and therefore develop longer, unstable crazes.

Although PMMA was not part of their dataset, these mechanisms help explain why PMMA, which can support limited shear yielding, exhibits a tougher response than PS.

4.2 Physical Aging Connection

Donald & Kramer also demonstrated that annealing below Tg suppresses shear and produces cleaner, simpler craze structures. Aging reduces excess free volume and restricts segmental mobility, which lowers the ability of the polymer to activate shear relaxation-consistent with modern free-volume interpretations.

4.3 How This Paper Supports the Chapter

The micrographs and analysis from Donald & Kramer connect molecular arguments to observable deformation:

- Mobility at the chain-segment level controls whether shear can form at a craze tip,

- Entanglement density determines craze stability,

- Free volume and aging modify the available deformation pathways.

Together, these principles help rationalize the brittle-tough contrast between PS and PMMA: the difference originates in mobility and entanglement constraints long before it appears as a mechanical property.

- Summary

Polystyrene and PMMA show how subtle changes in chemical structure led to major differences in mechanical behavior. Restricted segmental mobility lowers effective entanglement density, so deformation localizes into unstable crazes that fracture quickly. PMMA, with a less rigid ester side group and slightly higher entanglement density, maintains enough mobility to stabilize craze fibrils and eventually transition into shear yielding, absorbing more energy before failure.

This comparison illustrates the core structure–property logic of glassy polymers: chain mobility governs available deformation mechanisms, and those mechanisms determine toughness. By connecting molecular features to free volume, entanglement spacing, and craze stability, students can predict why two polymers with similar Tg values behave so differently in practice and apply the same reasoning to evaluate or design other amorphous materials.

References

Donald, A. M., & Kramer, E. (1982). The competition between shear deformation and crazing in glassy polymers. In JOURNAL OF MATERIALS SCIENCE (Vol. 17).

Fryer, D. S., Peters, R. D., Kim, E. J., Tomaszewski, J. E., De Pablo, J. J., Nealey, P. F., White, C. C., & Wu, W. L. (2001). Dependence of the glass transition temperature of polymer films on interfacial energy and thickness. Macromolecules, 34(16), 5627–5634. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma001932q

Narayan, S., & Anand, L. (2021). Fracture of amorphous polymers: A gradient-damage theory. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmps.2020.104164

Razavi, M., Huang, D., Liu, S., Guo, H., & Wang, S. Q. (2020). Examining an Alternative Molecular Mechanism to Toughen Glassy Polymers. Macromolecules, 53(1), 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.macromol.9b01987

White, R. P., & Lipson, J. E. G. (2016). Polymer Free Volume and Its Connection to the Glass Transition. In Macromolecules (Vol. 49, Issue 11, pp. 3987–4007). American Chemical Society. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.macromol.6b00215

Xie, R., Weisen, A. R., Lee, Y., Aplan, M. A., Fenton, A. M., Masucci, A. E., Kempe, F., Sommer, M., Pester, C. W., Colby, R. H., & Gomez, E. D. (2020). Glass transition temperature from the chemical structure of conjugated polymers. Nature Communications, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14656-8