4 Recycling of Polymer

Susmita Saha

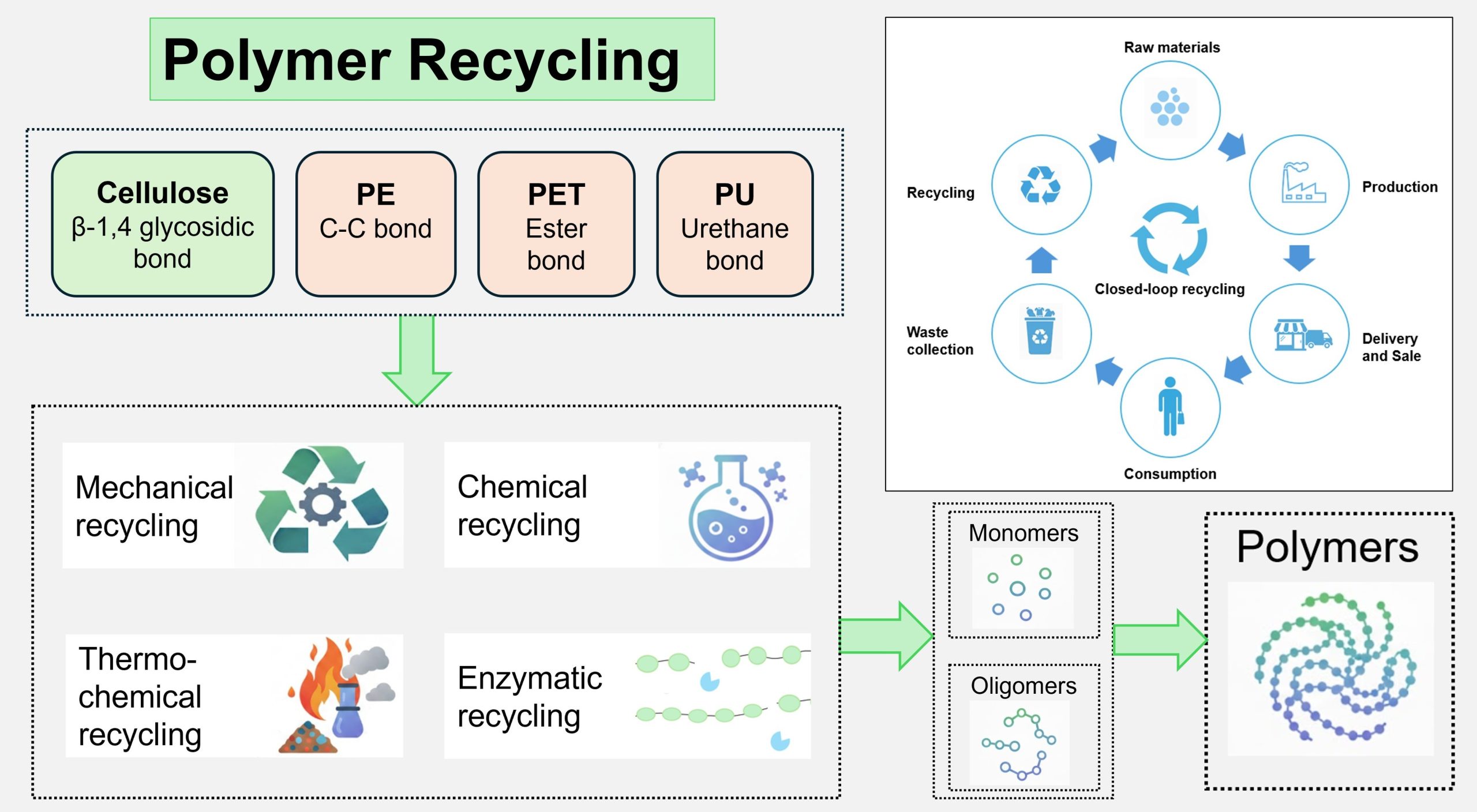

Graphical Abstract

1 Introduction

We inhabit a polymer world! These materials are ubiquitous, influencing our daily lives through the production of textiles, packaging, lifesaving medical devices, and advanced electronics. However, their longevity often extends beyond their intended purpose, accumulating in landfills and ecosystems, and resulting in environmental pollution. This raises difficult questions: Will the materials we create continue to accumulate faster than we can manage them responsibly? More importantly, what steps can we take to address this? One compelling solution is circularity: make the polymers, use them, and recycle them to make the next set of desired products. If you are ready to explore this approach, this chapter will guide you through the scientific principles and practical technologies of polymer recycling.

In 2022, we produced roughly 400 million tons of synthetic polymers/plastics (Houssini et al., 2025). From the production quantities of polymers, we can infer how much we rely on these materials in our lives. Mismanaged plastic waste contributes to microplastic pollution, greenhouse gas emissions from incineration. The advancement of effective recycling technologies is crucial for preserving the advantages of polymeric materials while minimizing their environmental impact. For graduate students and researchers, this chapter connects chemistry, materials science, and sustainability. Different polymers exhibit different chemistries, such as glycosidic bonds in cellulose, ester bonds in polyesters, and inert C-C backbones in polyolefins. As a result, mechanical, chemical, thermochemical, and biological recycling do not apply equally to all polymers. Therefore, understanding how polymer structure controls feasible recycling routes is essential.

This chapter, titled “Recycling of Polymer”, provides a structured, polymer-specific overview of major recycling strategies and the associated challenges. The chapter begins with a brief overview of polymer structures and applications, focusing on widely used polymers such as cellulose, polyethylene, polyethylene terephthalate, and polyurethanes, and their uses in products such as textiles, packaging, coatings, foams, and engineering components. The chapter then describes existing recycling routes in detail, including mechanical, chemical, thermochemical, and biochemical recycling approaches. Overall, this chapter serves as a roadmap for understanding how polymer structure and bonding determine recycling options, and how those options can be engineered to support more sustainable waste management for polymeric materials.

Learning objectives:

- Explain the concept of polymer recycling and distinguish it from other end-of-life options, such as landfill and incineration.

- Describe why polymer recycling is necessary, considering both environmental impacts and economic benefits.

- Compare different polymer recycling methods and evaluate the merits and demerits of each process for different polymer classes.

- Discuss the different recovered products, such as monomers, oligomers, and regenerated polymers, from various recycling approaches, and evaluate their performance in manufacturing new products.

2 Polymer Recycling Principles and Techniques

Polymer recycling is fundamentally controlled by chemical structure; there is no “one size fits all” approach. The types of bonds and functional groups in a polymer determine how (or whether) it can be depolymerized, dissolved, or reprocessed. In this chapter, these principles are explored using four widely used polymers: cellulose, which contains β-1,4-glycosidic linkages; polyethylene (PE), whose backbone consists only of C–C and C–H bonds; polyethylene terephthalate (PET), with ester linkages; and polyurethane (PU), with urethane linkages. For each of these polymers, the corresponding recycling technologies are discussed to show how polymer structure directly shapes feasible recycling routes and the types of products that can be recovered.

2.1 Cellulose

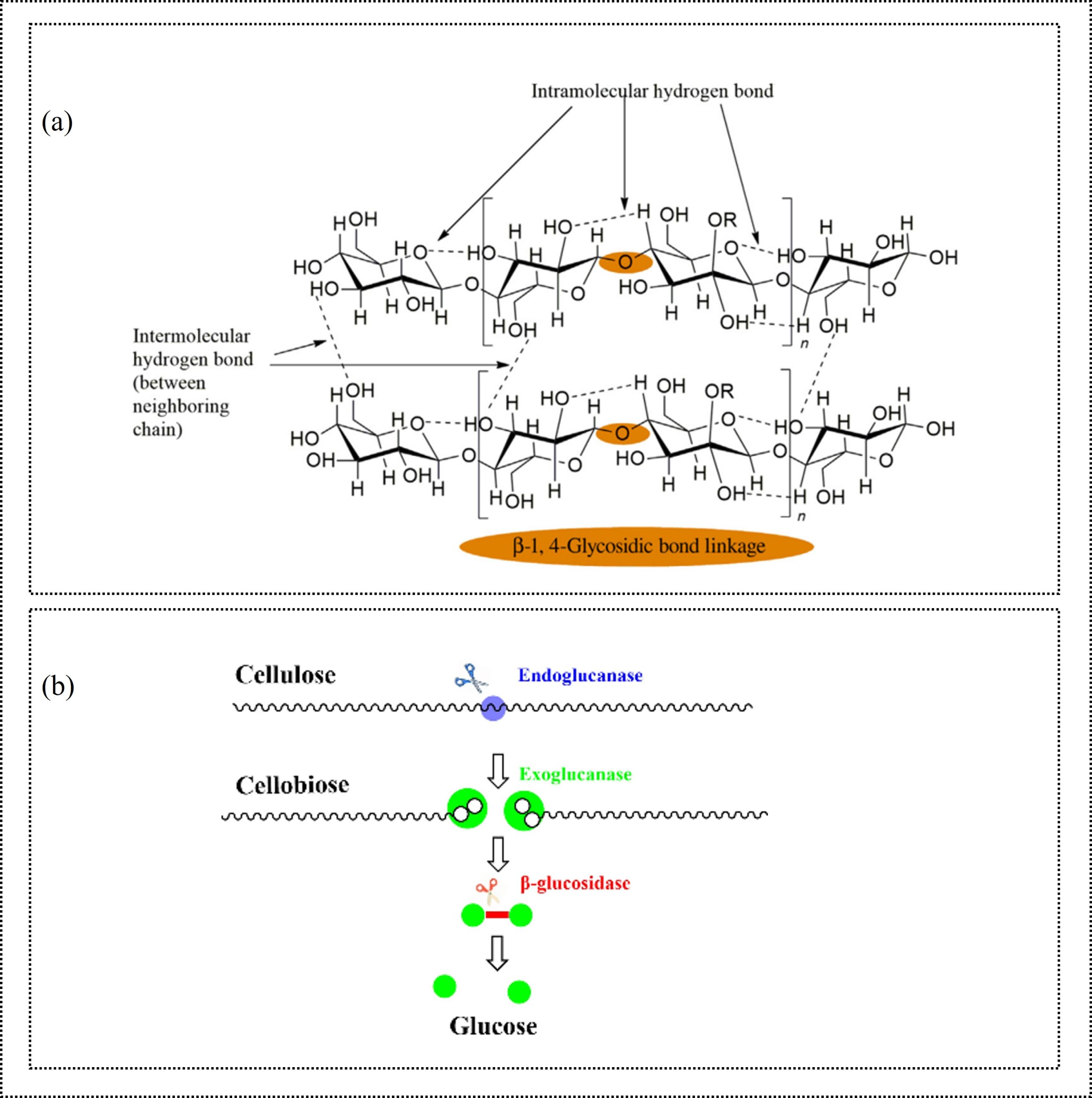

Cellulose is the most abundant biopolymer on Earth, primarily obtained from wood and cotton fibers. It is a linear polysaccharide composed of D-glucose monomers linked by β-1,4-glycosidic linkages (Erdal & Hakkarainen, 2022). Figure 1(a) shows the intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonds of cellulose chains, which contribute to its higher crystallinity, making the polymer mechanically strong but insoluble in most organic solvents. Cellulose is inherently biodegradable because cellulase enzymes can cleave its glycosidic bonds, as shown in Figure 1(b) (Erdal & Hakkarainen, 2022). Enzymes convert the polymer into glucose monomers or oligomers that can be further utilized in biochemical or industrial processes. Although native cellulose is environmentally benign, chemical modifications used to produce various materials, such as cellulose acetate, rayon, and other functional coatings, can disrupt biodegradation. In these cases, chemical recycling can be more promising. For example, chemical recycling can involve deacetylation of cellulose esters to recover cellulose and alkaline pretreatment to remove dyes and finishes from textile fabrics (El Seoud et al., 2020). Recovered cellulose can be dissolved in ionic liquids or in N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide (NMMO). NMMO is used in the Lyocell process that converts wood pulp or other cellulosic materials into regenerated fibers (Klemm et al., 2005). In this way, recycling of cellulosic products provides recovered cellulose or glucose, which can be used to produce regenerated cellulose fibers, cellulose films, hydrogels, paper products, or biobased chemicals and fuels.

The following YouTube video on “Biochemical enzymatic hydrolysis” describes how enzymatic hydrolysis is used to convert biomass containing cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin into renewable energy sources such as biodiesel. This process provides an insight into the conversion of discarded cellulosic products into renewable energy sources.

2.2 Polyethylene

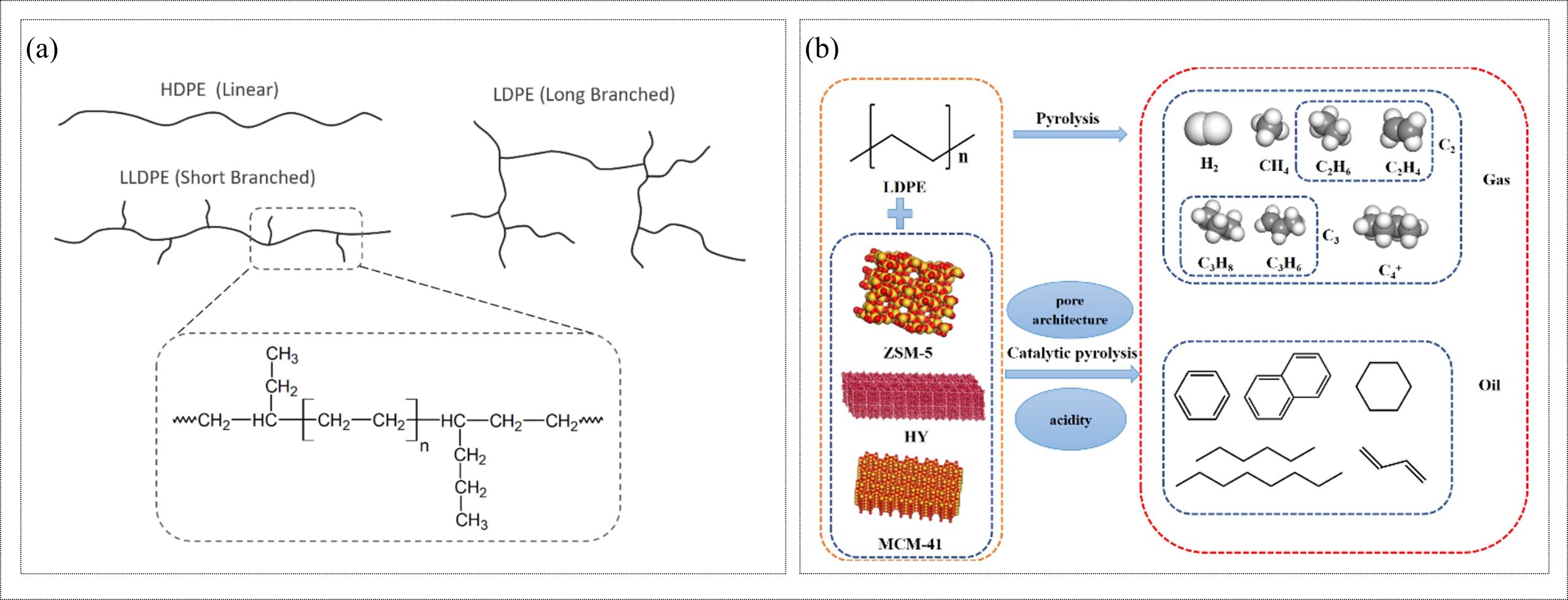

Polyethylene (PE) holds the largest production share among all synthetic polymers. It is produced by chain-growth polymerization of ethylene using free-radical initiators for low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and coordination catalysts such as Ziegler–Natta, chromium, or metallocene systems for high-density (HDPE) and linear low-density polyethylene (LLDPE) (Schwab et al., 2024; Shamiri et al., 2014). Differences in catalyst type and polymerization conditions cause variations in chain branching, as shown in Figure 2(a). Therefore, the mechanical properties of different kinds of PE polymers are also varied. PE is extensively used in packaging films and bags, containers, geomembranes, and a wide range of household and industrial products. The PE backbone consists only of C–C and C–H bonds and lacks hydrolysable functional groups; therefore, it is not biodegradable and can persist in the environment for decades, responsible for environmental pollution. Mechanical recycling of PE is widely practiced, but repeated processing, contamination, and oxidation often degrade material quality. As a result, thermochemical and catalytic routes, such as pyrolysis, gasification, and catalytic cracking, are used as chemical recycling options for PE (Liu et al., 2023; Lobodin et al., 2025). In these processes, PE is thermally or catalytically depolymerized into mixtures of hydrocarbons, ranging from gases to liquid oils and waxes, as shown in Figure 2(b). Although true monomer (ethylene) recovery from PE products remains challenging at the commercial scale, these catalytic routes provide a pathway to convert PE waste into useful chemical intermediates.

2.3 Polyethylene terephthalate

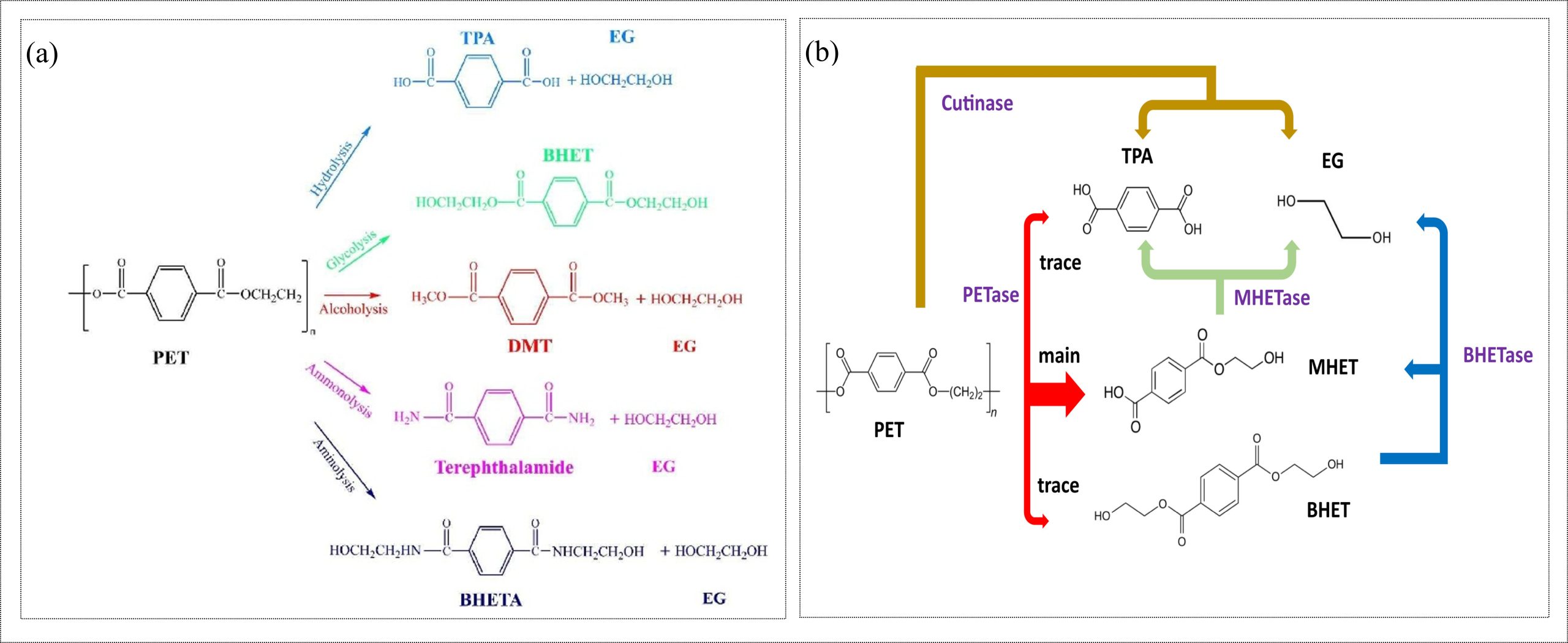

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is a synthetic polyester produced by the step-growth polymerization of terephthalic acid (TPA) and ethylene glycol (EG) (Abedsoltan, 2023). PET is widely used in textiles, drinking water bottles, food packaging, and films. Since PET is not biodegradable, discarded PET waste can fragment into microplastics and cause environmental pollution. Mechanical recycling of PET often results in downcycling, whereas chemical recycling can recover monomers or other valuable chemicals (Payne & Jones, 2021). The major chemical recycling methods include glycolysis, alcoholysis (methanolysis), hydrolysis, aminolysis, and ammonolysis (Abedsoltan, 2023; Umdagas et al., 2025). Among these, glycolysis is the most widely commercialized, where PET is reacted with ethylene glycol (EG) to recover bis(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate (BHET). Hydrolysis can be carried out under alkaline, neutral, or acidic conditions to recover TPA and EG. Alcoholysis converts PET into dimethyl terephthalate (DMT) and EG using alcohols, while aminolysis produces bis(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalamide (BHETA) using amine. Ammonolysis, performed with ammonia, generally produces terephthalamide and EG. Besides this, pyrolysis is also used to recycle PET materials, particularly when they contain more impurities (Abedsoltan, 2023). Figure 3(a) represents the different chemical recycling techniques of PET along with the respective recovered chemicals. Enzymatic hydrolysis of PET is also possible because the polymer backbone contains hydrolysable ester bonds. PET-hydrolyzing enzymes such as PETase and cutinases can depolymerize PET into TPA and EG under mild conditions (García, 2022), as shown in Figure 3(b). The recovered monomers and intermediates from these chemical and enzymatic processes can be reintroduced into PET manufacturing or used as feedstocks for other polymer and chemical systems.

2.4 Polyurethane

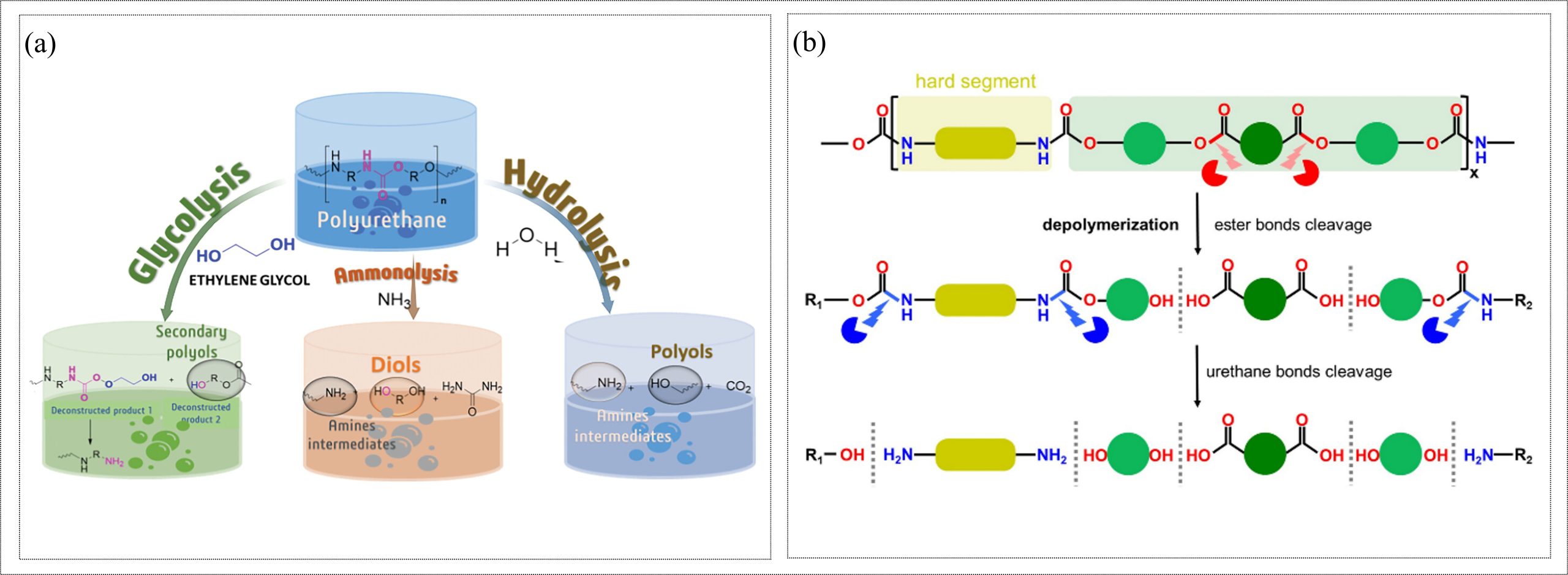

Polyurethanes (PUs) are a group of synthetic polymers (thermoplastic or thermosetting) produced from diisocyanates and diols/polyols through step-growth polymerization, often with chain extenders and crosslinkers (Rossignolo et al., 2024). By varying the hard segment (isocyanate + chain extender) and the soft segment (polyol), PUs can be used to produce flexible foams and elastomers, as well as rigid coatings, adhesives, and sealants (Kemona & Piotrowska, 2020). Chemical recycling of PUs primarily includes glycolysis, hydrolysis, and ammonolysis, which cleave the ester and/or urethane (carbamate) linkages to recover polymeric precursors, as shown in Figure 4(a). Glycolysis is a transesterification reaction in which hydroxyl groups of glycols attack the carbonyl carbons of the urethane bonds, resulting in the formation of polyols (Chavez-Linares et al., 2025). Hydrolysis of PUs is carried out using water in liquid or steam form, which produces polyols, amines intermediates, and carbon dioxide (Kemona & Piotrowska, 2020). Ammonolysis also attacks the urethane bond of PUs using amines and produces polyols, substituted ureas, and amines intermediates. Enzymatic recycling of PUs involves enzymes such as lipases, amidases, esterases, and recently identified urethanases, which can cleave specific bonds present in PUs (Raczyńska et al., 2024). In general, esterases preferentially hydrolyze ester bonds in polyester-based PUs, whereas urethanases target urethane linkages in the PU backbone, as depicted in Figure 4(b).

3. Discussion of a Peer-Reviewed Paper

Paper Title: Polyester/Cotton-Blended Textile Waste Fiber Separation and Regeneration via a Green Chemistry Approach

3.1 Brief Overview of the Paper

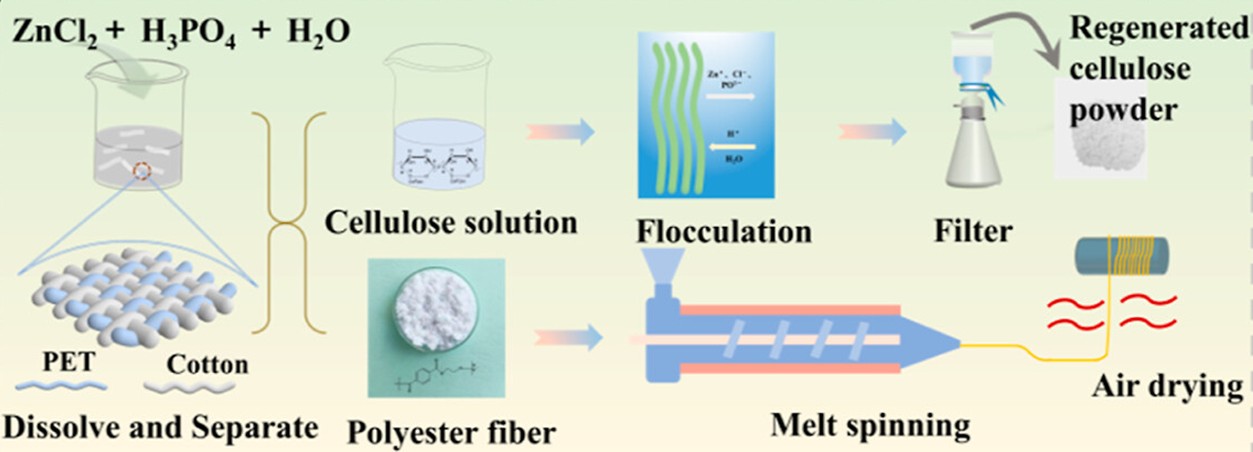

In this article, Yang et al. proposed a green chemical recycling approach for two polymers in a blended state (Yang et al., 2024). These two polymers are widely used in the textile industry, and these are cellulose and polyester. The authors demonstrated how to separate and regenerate polyester and cellulose from (PET/cotton) blended fabrics in a way that is efficient, gentle, and scalable. The authors noted that blended textiles end up in landfills or incinerators, resulting in greenhouse gas emissions and solid-waste burdens. Mechanical recycling can shred fabrics into fibers, but it shortens fibers and degrades quality. Traditional chemical methods either rely on very strong acids that severely degrade cellulose or on harsh organic solvents that are expensive, toxic, and hard to recover. In contrast, the authors proposed a green, metal-salt-hydrate deep eutectic solvent (DES) based on ZnCl2, H3PO4, and H2O as a room-temperature medium that selectively dissolved cotton cellulose while leaving polyester almost intact. The process started by immersing chopped PET/cotton fabric in this DES; cotton rapidly dissolved to form a viscous cellulose solution, whereas PET remained as undissolved fibers, as illustrated schematically in Figure 5.

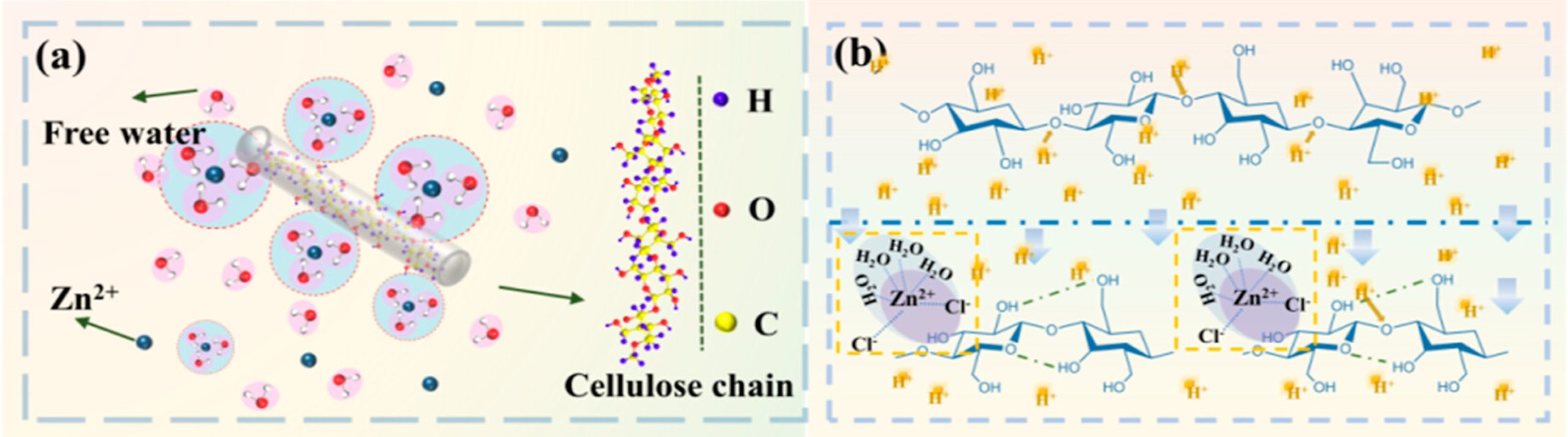

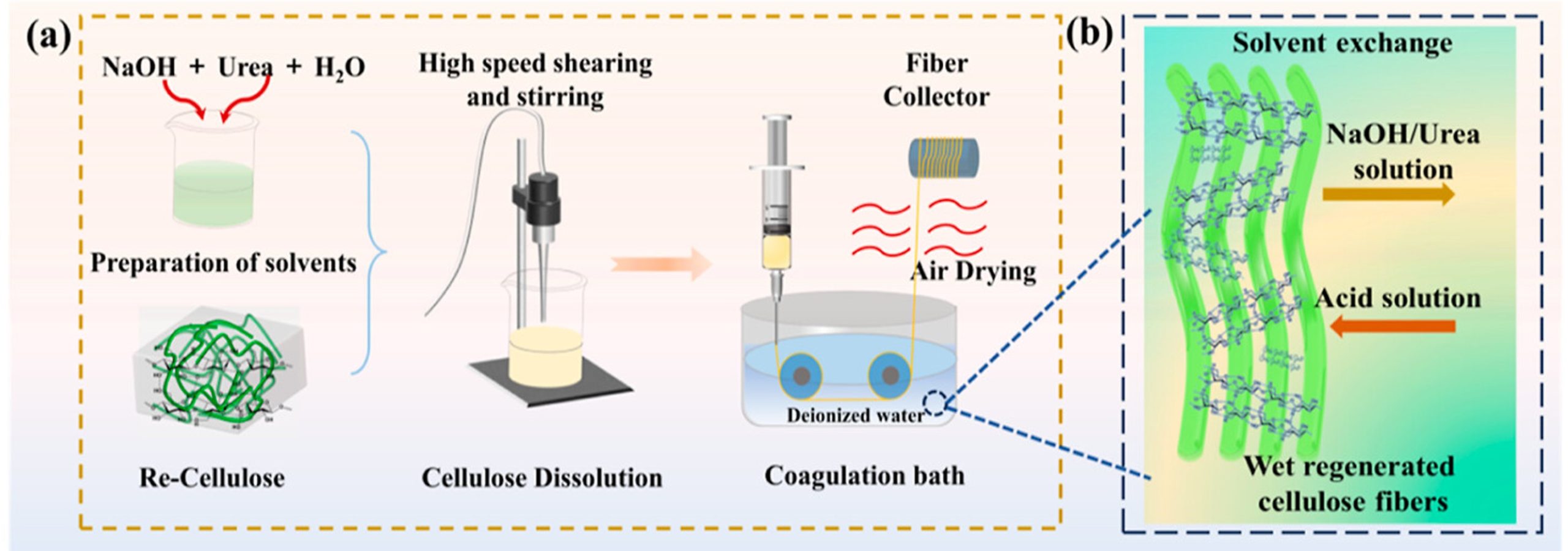

Mechanistically, the DES behaves as a “hydrogen-bond scissor”: Zn²⁺, coordinated with water, and protons from phosphoric acid compete for hydrogen bonds within the cellulose structure, disrupt intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonding, and thereby dissolve cellulose without extensively hydrolyzing the glycosidic backbone, as shown in Figure 6. On the other hand, due to a lack of accessible hydroxyl networks, PET is not attacked under these conditions and can be physically recovered. After dissolution, cellulose was coagulated in water, dried to a powder, then redissolved in a NaOH/urea/H2O system and wet-spun into regenerated cellulose fibers; the separated PET fibers were washed, dried, and melt-spun into regenerated polyester fibers, as shown in Figure 7.

Structural and thermal analyses using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray Diffraction (XRD), Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA), and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) showed that the regenerated cellulose converts from cellulose I to cellulose II with reduced crystallinity. In contrast, PET retains its characteristic ester and aromatic bands and exhibits nearly identical melting behavior, confirming that the deep eutectic solvent (DES) does not chemically damage the polyester component. Mechanical testing demonstrated that regenerated cellulose fibers exhibited slightly reduced tensile strength and elongation, and that recycled PET fibers showed greater strength loss due to repeated melt processing rather than the separation step itself. Overall, the study demonstrated a fiber-to-fiber circular recycling route for PET/cotton blends under relatively mild, potentially scalable conditions.

3.2 Relevance of the Article to This Chapter

This paper closely aligns with this chapter in several ways. First, it provides a concrete example of the chemical recycling concepts of cellulose: selective dissolution based on hydrogen-bond competition, regeneration into new fibers, and the transformation of cellulose I to cellulose II. Second, the work mentions the PET recycling option: although polyester is not depolymerized via glycolysis or hydrolysis, it is separated from blends and reprocessed into PET fibers. Third, the paper shows the difficulty of recycling blended materials. Finally, by demonstrating that both separated polymer fractions can be re-spun into fibers, the paper strengthens the idea that advanced recycling technologies are moving beyond simple downcycling toward true material circularity.

4 Conclusion

The recyclability of a polymer is fundamentally controlled by its chemical structure, and this chapter illustrated that principle using four widely used polymers. In summary, cellulose with β-1,4-glycosidic bonds can be dissolved, regenerated, or enzymatically hydrolyzed; PE with an inert C–C backbone is mainly suited to thermochemical routes such as pyrolysis and catalytic cracking, while PET with ester linkages and PU with urethane linkages can undergo solvolysis and, in some cases, enzymatic depolymerization. Recovered materials from different recycling methods, such as mechanical, chemical, thermochemical, and biological, were also evaluated for their suitability to produce new materials. Together, these examples show that understanding the relationship between polymer structure and recycling technology is essential for designing more sustainable and closed-loop recycling pathways.

Break it Down! Polymer Recycling Quiz

References

Abedsoltan, H. (2023). A focused review on recycling and hydrolysis techniques of polyethylene terephthalate. Polymer Engineering and Science, 63(9), 2651–2674. https://doi.org/10.1002/pen.26406

Chavez-Linares, P., Hoppe, S., & Chevalot, I. (2025). Recycling and Degradation Pathways of Synthetic Textile Fibers such as Polyamide and Elastane. In Global Challenges (Vol. 9, Issue 4). John Wiley and Sons Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/gch2.202400163

Daywey, C. (2013, August 13). The three main families of PE films. KYMC. https://www.kymc.com/webls-tran-c/msg/msg123.html

Deshavath, N. N., Veeranki, V. D., & Goud, V. V. (2019). Lignocellulosic feedstocks for the production of bioethanol: Availability, structure, and composition. In Sustainable Bioenergy: Advances and Impacts (pp. 1–19). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817654-2.00001-0

El Seoud, O. A., Kostag, M., Jedvert, K., & Malek, N. I. (2020). Cellulose Regeneration and Chemical Recycling: Closing the “Cellulose Gap” Using Environmentally Benign Solvents. In Macromolecular Materials and Engineering (Vol. 305, Issue 4). Wiley-VCH Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1002/mame.201900832

Erdal, N. B., & Hakkarainen, M. (2022). Degradation of Cellulose Derivatives in Laboratory, Man-Made, and Natural Environments. Biomacromolecules, 23(7), 2713–2729. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.2c00336

García, J. L. (2022). Enzymatic recycling of polyethylene terephthalate through the lens of proprietary processes. Microbial Biotechnology, 15(11), 2699–2704. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.14114

Houssini, K., Li, J., & Tan, Q. (2025). Complexities of the global plastics supply chain revealed in a trade-linked material flow analysis. Communications Earth & Environment, 6, Article 2169. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02169-5

Kemona, A., & Piotrowska, M. (2020). Polyurethane recycling and disposal: Methods and prospects. Polymers, 12(8), 1752. https://doi.org/10.3390/POLYM12081752

Klemm, D., Heublein, B., Fink, H. P., & Bohn, A. (2005). Cellulose: Fascinating biopolymer and sustainable raw material. Angewandte Chemie – International Edition, 44(22), 3358–3393. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200460587

Li, C., Wu, J., Shi, H., Xia, Z., Sahoo, J. K., Yeo, J., & Kaplan, D. L. (2022). Fiber-Based Biopolymer Processing as a Route toward Sustainability. Advanced Materials, 34(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202105196

Liu, T., Li, Y., Zhou, Y., Deng, S., & Zhang, H. (2023). Efficient Pyrolysis of Low-Density Polyethylene for Regulatable Oil and Gas Products by ZSM-5, HY and MCM-41 Catalysts. Catalysts, 13(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/catal13020382

Lobodin, V. V., Parks, J. E., Finney, C. E. A., Daemen, L., Anovitz, L. M., Ryder, M. R., Purdy, S. C., & Tsouris, C. (2025). Hydrogen Production from Polyethylene Pyrolysis. ACS Omega. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.5c09609

Payne, J., & Jones, M. D. (2021). The Chemical Recycling of Polyesters for a Circular Plastics Economy: Challenges and Emerging Opportunities. ChemSusChem, 14(19), 4041–4070. https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.202100400

Raczyńska, A., Góra, A., & André, I. (2024). An overview on polyurethane-degrading enzymes. Biotechnology Advances, 77, 108439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2024.108439

Rossignolo, G., Malucelli, G., & Lorenzetti, A. (2024). Recycling of polyurethanes: where we are and where we are going. Green Chemistry, 26(3), 1132–1152. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3gc02091f

Schwab, S. T., Baur, M., Nelson, T. F., & Mecking, S. (2024). Synthesis and Deconstruction of Polyethylene-type Materials. Chemical Reviews, 124(5), 2327–2351. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.3c00587

Shamiri, A., Chakrabarti, M. H., Jahan, S., Hussain, M. A., Kaminsky, W., Aravind, P. V., & Yehye, W. A. (2014). The influence of Ziegler-Natta and metallocene catalysts on polyolefin structure, properties, and processing ability. Materials, 7(7), 5069–5108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma7075069

Umdagas, L., Orozco, R., Heeley, K., Thom, W., & Al-Duri, B. (2025). Advances in chemical recycling of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) via hydrolysis: A comprehensive review. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2025.111246

Yang, K., Wang, M., Wang, X., Shan, J., Zhang, J., Tian, G., Yang, D., & Ma, J. (2024). Polyester/cotton-blended textile waste fiber separation and regeneration via a green chemistry approach. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 12(11), 4530–4538. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c07707