23 Principles, Techniques, and Applications

cong meng

Abstract

The advancement of polymer science relies fundamentally on the precise elucidation of structure-property relationships. As polymeric materials evolve from simple commodities to complex, multi-functional systems used in aerospace, biomedical, and electronic applications, the analytical techniques required to understand them must also become increasingly sophisticated. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the essential characterization methodologies necessary for a holistic understanding of polymeric materials, spanning from the atomic scale to macroscopic industrial processing. We begin by examining the foundation of polymer identity: Structure and Molecular Weight Characterization. The review details the critical roles of Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC/SEC) in determining molecular weight distributions, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy for resolving chemical sequences and tacticity, and Mass Spectrometry (MS) for precise ionization and end-group analysis. Moving from the molecular to the supramolecular level, the abstract highlights Morphology and Microstructure Characterization. We discuss how the visualization of phase separation, crystallinity, and surface topography is achieved through the complementary use of Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), providing insights into how processing history dictates internal structure. Furthermore, the thermodynamic and mechanical durability of materials is explored through Thermal and Mechanical Property Characterization. Techniques such as Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA), and Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) are synthesized to explain transitions like the glass transition temperature and viscoelastic behavior under load. The review also addresses the critical interaction of materials with their environment via Optical and Interface Property Characterization, utilizing UV-Vis, FTIR, Ellipsometry, and Contact Angle measurements to quantify surface energy, wettability, and chemical functionality at interfaces. Finally, we bridge the gap between laboratory synthesis and industrial utility through Processing and Application-Related Characterization. This section emphasizes the importance of Melt Flow Index (MFI), Rheology, and destructive testing (Tensile/Flexural, Fatigue) in predicting material behavior under real-world manufacturing and service conditions. Collectively, this multifaceted analytical approach provides the roadmap for designing next-generation polymeric materials with tailored properties.

Introduction

Polymers have become ubiquitous in modern society, serving as the backbone for materials ranging from everyday packaging to sophisticated drug delivery systems and high-performance composites. The versatility of polymers stems from the infinite possibilities in their chemical structure, molecular weight distribution, and processing history. However, this versatility introduces a significant challenge: the inherent complexity of polymer systems. Unlike small molecules with defined structures, polymers are statistical mixtures that exhibit hierarchical structures across multiple length scales. Therefore, the successful development and deployment of new polymeric materials demand a rigorous, multi-dimensional approach to characterization. This paper aims to provide a structured overview of the primary analytical techniques used to interrogate polymers, categorized by the specific material attributes they reveal.

The first and most fundamental level of analysis concerns Structure and Molecular Weight. The physical properties of a polymer—such as toughness, melt viscosity, and solubility—are inextricably linked to the size of its chains and their chemical architecture. Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), also known as Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), serves as the workhorse for determining molecular weight averages and polydispersity indices. Understanding the distribution of chain lengths is critical, as it dictates processing windows and mechanical failure modes. Complementing this, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides atomic-level resolution of the polymer backbone, allowing researchers to determine copolymer composition, stereoregularity (tacticity), and branching structures. Furthermore, advances in Mass Spectrometry (MS), particularly with soft ionization techniques like MALDI-TOF, have enabled the precise analysis of oligomers and end-group functionalization, bridging the gap between synthetic chemistry and materials science.

Beyond the single chain, polymers organize into complex supramolecular structures. Morphology and Microstructure Characterization is essential for visualizing how polymer chains pack, crystallize, or phase-separate in the solid state. Techniques such as Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) allow scientists to observe domain sizes in block copolymers, dispersion quality in nanocomposites, and fracture surfaces in failed parts. While electron microscopy provides 2D projections or surface topologies, Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) offers 3D topographical mapping and phase imaging, capable of distinguishing between hard and soft domains on a surface without the need for extensive sample staining.

However, a polymer’s structure is only relevant if it can withstand the thermal and mechanical stresses of its intended application. Thermal and Mechanical Property Characterization provides the quantitative data needed for engineering design. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) is indispensable for identifying critical thermal transitions, including the glass transition and melting point , which define the service temperature range of the material. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) assesses thermal stability and decomposition profiles, ensuring the material can survive processing temperatures. To understand viscoelastic behavior—how a polymer acts as both a solid and a liquid—Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) is employed to measure storage and loss moduli as a function of temperature and frequency.

In many applications, particularly in coatings, electronics, and biomaterials, the surface properties are just as critical as the bulk. Optical and Interface Property Characterization techniques focus on these interactions. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and UV-Vis spectroscopy are standard tools for identifying chemical functional groups and optical transparency. For thin films and coatings, Ellipsometry measures thickness and refractive index with angstrom-level precision. Furthermore, the interaction between a polymer surface and liquids is characterized through Contact Angle measurements and Surface Energy calculations, which are vital for predicting adhesion, wettability, and biocompatibility.

Finally, the translation of a polymer from a laboratory curiosity to a commercial product requires Processing and Application-Related Characterization. This category focuses on how the material behaves under flow and load. The Melt Flow Index (MFI) provides a quick quality control metric for thermoplastics, while detailed Rheology studies elucidate complex flow behaviors like shear thinning, which are crucial for injection molding and extrusion. Mechanical testing, including Tensile, Flexural, and Fatigue/Fracture testing, defines the ultimate limits of the material, providing the stress-strain data necessary for structural integrity simulations.

In summary, no single technique can provide a complete picture of a polymeric material. By integrating data from structural, morphological, thermal, interfacial, and mechanical analyses, researchers can construct a comprehensive understanding of the material’s behavior, paving the way for targeted innovation and robust application.

Learning Objective

Understand the overall framework of polymer characterization, and distinguish the goals and applicable scenarios of structural characterization, physical property characterization, and chemical property characterization. Master the basic principles of common polymer characterization techniques, and the key points of experimental design and data interpretation through several different characterization methods. Introduce the key considerations in experimental design, sample preparation, selection of characterization conditions, sources of error, repeatability and reproducibility, data processing and statistical analysis. Through case studies, demonstrate how to select appropriate characterization combinations based on different application goals, and convert characterization results into conclusions about material performance, processability and potential applications.

Method

Structural and Molecular Weight Characterization

Gel permeation chromatography (GPC/SEC) is an important characterization method for the molecular weight distribution and the width of the molecular weight distribution of polymers. By separation in porous fillers (columns), sample molecules are separated by equivalent volume (the extent to which they enter the pore size), and usually a volumetric exclusion chromatogram is obtained. Consolidation distribution parameters such as number-average molecular weight Mn, approximate weight-average molecular weight Mw, molecular weight distribution index ß = Mw/Mn, and polydispersancy index d= Mw/Mn are calculated. Relying on calibration standards (ideally with polystyrene, polymer scales or absolute molecular weight detectors such as multi-angle light scattering, viscosity detectors, differential refraction, etc.) and the selection of solvent systems, GPC can provide reliable results over a wide molecular weight range. For polymer synthesis and modified materials, understanding molecular weight and molecular weight distribution is of decisive significance for predicting melt viscosity, mechanical properties, processing behavior and thermal stability. By combining multi-mode detection (such as ALS- light scattering, VDI- viscosity, RI- differential refraction), absolute molecular weight and molecular weight distribution information can be obtained, avoiding deviations from comparison scales.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) provides complementary information in molecular weight and structural characterization. The chemical shifts, peak areas and coupling modes of 1H, 13C and other nuclei can quantitatively evaluate the monomer composition, branching degree, end group content of polymers and the block structure of copolymers. The degree of polymerization and molecular weight of polymers can be estimated by means of the free ratio, end group labeling or internal standard method. However, compared with GPC, NMR usually pays more attention to structural features rather than precise molecular weight in polymer systems.

The role of mass spectrometry (MS) in polymer analysis is increasingly prominent. Polymer ionization techniques (such as ESI, MALDI-TOF-MS, rigid ionization/matrix-assisted ionization) can provide information on the molecular weight distribution of polymer series, end group types, repeat unit structures, etc. For linear, branched, block or cyclic polymers, MS can reveal the differences in terminal groups and microstructure, although high-molecular-weight polymers may encounter the problem of decreased ionization efficiency in conventional MS analysis. In recent years, by combining MALDI-TOF-MS and GPC data, full mutual evidence of molecular weight distribution can be achieved. In addition, the combination of polymer analysis-related technologies (such as polymerization kinetics, end-group reactions, and optimization of ionization strategies) can assist in predicting processing performance during the material design stage.

Morphology and Microstructure Characterization

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) together form the fundamental observation methods for material morphology. TEM can observe grains, phase separation, aggregation states, interfaces of polymer nanoparticles, etc. at the nanoscale, providing lattice information and particle size distribution. Sample preparation usually requires ultrathin sectioning, negative staining, or metal deposition to enhance contrast. SEM mainly focuses on surface morphology and is suitable for observing thin films, coatings, micro roughness, pore structures, and surface topography of phase separation. For polymer materials, field emission SEM (FE-SEM), environmental SEM, or low vacuum SEM can be used to reduce sample preparation damage to organic materials.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) provides three-dimensional surface topography and has mechanical imaging modes (tip-sample interaction force) to obtain intrinsic elastic modulus, adhesion force, and other information. AFM is very useful in the fields of polymer films, colloidal aggregation states, and nanofibers. Combined with phase imaging and force spectroscopy curves, it can resolve phase separation, crystallization, and plasticity distinctions at the nanoscale.

Thermal Properties and Mechanical Performance Characterization

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) is the core method for evaluating the thermal transition of polymers, capable of determining the glass transition temperature (Tg), melting temperature (Tc), potential crystallization temperature, and changes in specific heat capacity. Through different cooling/heating rates, the crystallization kinetics and thermal behavior of copolymers can be analyzed. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) reveals the mass loss pattern of the material as the temperature increases, providing information on thermal stability, decomposition temperature, water/solvent residue, etc. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) provides the storage modulus and loss modulus of the material under different temperatures, frequencies, and strain conditions, directly reflecting the elastic/viscous behavior and glass transition of the material. Coupled analysis of DSC and DMA can obtain the coupling information of thermal events and mechanical responses in the same material system, such as viscoelastic changes near Tg and potential phase separation behavior.

Melt Index (MFI/MI) and rheological tests in processing and application-related characterization are crucial for determining processing properties and selecting processing equipment. Rheological analysis (such as creep, viscoelastic response under shear conditions) reveals the flow resistance and shear viscosity reduction behavior of the material during processing. Mechanical characterization tests such as tensile, bending, fatigue, and fracture tests directly provide key performance indicators of the material, such as Young’s modulus, tensile strength, fracture toughness, and fatigue life.

Optical and Interface Property Characterization

Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (UV-Vis) is used to analyze the optical band gap, changes in absorption peak positions, and intermolecular conjugated structures of materials. For polymer films or composite materials, UV-Vis can assess the effects of dopants and additives on optical properties. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) provides information on the vibration of molecular characteristic groups, enabling the identification of functional groups, formation/rupture of chemical bonds, and tracking of chemical transformations during polymer modification. Ellipsometry/polarized light correlation techniques (such as ELLIPSOMETRY, polarized light microscopy) are used to determine the optical constants of films, thickness, and optical heterogeneity of interface layers. Contact angle measurement and surface energy/interfacial tension measurement reveal wettability, hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity, and the effectiveness of surfactants or modified layers.

In terms of processing and application, surface energy and interfacial tension are highly correlated with coating adhesion, phase separation behavior, and interfacial wettability. In experiments, methods such as XPS and AFM are often combined to obtain a comprehensive understanding of chemical composition and surface energy.

Processing and Application-related Characterizations

Melt Flow Index (MFI/MI) is a standard parameter for measuring the processing fluidity of polymers, and is often used to evaluate the volume flow capacity of the melt under specific temperatures and shear rates. A high MFI typically indicates good processing performance and low melt viscosity, but it may also come with a trade-off in mechanical properties. Rheological tests (such as rotational viscoelasticity tests on rheometers) provide data on shear dependence, time dependence, and temperature dependence, and are important tools for measuring the processing process (extrusion, injection molding, blow molding).

In terms of mechanical tests, tensile and bending tests provide indicators such as strength, fracture toughness, and elongation. Fatigue and fracture tests reveal the fatigue life, crack propagation rate, and failure mode of the material under repeated loads. For polymer composites, it is also necessary to combine the bonding strength of the interface and the characterization of the dispersion state of the fillers to comprehensively evaluate the reliability of the material in practical applications.

Discussion of a Peer-Reviewed Paper

Overview

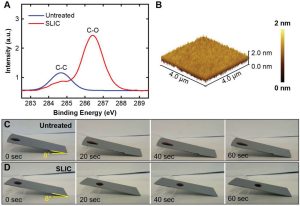

This study focuses on the performance of the texture-free, smooth hydrophilic (SLIC) surface in the interaction between blood and bacteria.1 Slippery surfaces (i.e., surfaces that display high liquid droplet mobility) have received significant attention for their advantages in multiple thermofluidic and biofluidic applications like condensation heat transfer, drag reduction, biofouling, miniaturized lab-on-a-chip platforms, etc. Slippery surfaces can be broadly classified as: i) super-repellent surfaces, ii) lubricant-infused surfaces, and iii) non-textured, all-solid surfaces (with covalently attached brushes) based on their underlying mechanism for slipperiness. Typically, super-repellent surfaces and lubricant-infused surfaces utilize textured substrates with lubricant (air or an immiscible liquid) trapped within the texture, inducing slip at the droplet-substrate interface, resulting in high droplet mobility on the surface. Despite the appeal of super-repellent surfaces and lubricant-infused surfaces, they are prone to loss in slipperiness due to texture damage, loss of trapped air due to dissolution over time, depletion of liquid lubricant due to evaporation overtime, etc. On the other hand, slippery non-textured, all-solid surfaces consist of smooth solid substrates with covalently attached oligomeric or polymeric brushes. Slippery non-textured, all-solid surfaces have been receiving increasing attention because they mitigate the common texture-related concerns prevalent in super-repellent surfaces and lubricant-infused surfaces. Among non-textured, all-solid, slippery surfaces, almost all are hydrophobic. In this work, elucidated the design of non-textured, all-solid, slippery hydrophilic surfaces; such SLIC surfaces are counter-intuitive because water droplets spread (rather than bead up) on SLIC surfaces suggesting higher adhesion, and yet water droplets easily slide past SLIC surfaces implying slipperiness. SLIC surfaces constitute an emerging class of surfaces, and their potential biomedical applications are yet to be investigated. By covalently grafting polyethylene glycol (PEG) brushes onto the smooth substrate, the SLIC surface achieves both hydrophilicity and slipperiness, and significantly reduces the adhesion and proliferation of platelets, white blood cells, and bacteria (Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus). Compared with the untreated silicon substrate, the adhesion of blood components decreased by approximately two orders of magnitude, and the adhesion of bacteria also decreased by nearly two orders of magnitude. Moreover, it has no significant toxicity to blood cells. These results suggest that the SLIC surface has potential applications in blood-contacting biomedical devices, possibly by inhibiting protein adsorption and biofilm formation through an ordered hydration layer, thereby enhancing anti-fouling performance and biocompatibility.

In polymer coursework, we learn about hydrophilic polymers such as poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), poly(methyl methacrylate) derivatives, zwitterionic polymers, and hydrogel-forming polymers. These materials resist protein adsorption and cell adhesion by creating a highly hydrated layer that presents a low interfacial energy to approaching biomolecules.

Figure illustrate how the slippery, hydrated polymer layer reduces nonspecific binding of blood proteins, platelets, and bacteria, thereby minimizing fouling. The connection to polymers lies in understanding how polymer composition, chain density, and hydration shell translate into anti-fouling performance.

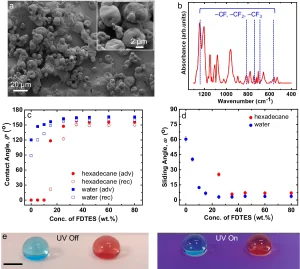

Color morphing refers to color change in response to an environmental stimulus. Photochromic materials allow color morphing in response to light, but almost all photochromic materials suffer from degradation when exposed to moist/humid environments or harsh chemical environments. One way of overcoming this challenge is by imparting chemical shielding to the color morphing materials via superomniphobicity. However, simultaneously imparting color morphing and superomniphobicity, both surface properties, requires a rational design. In this work2, they systematically design color morphing surfaces with superomniphobicity through an appropriate combination of a photochromic dye, a low surface energy material, and a polymer in a suitable solvent (for one-pot synthesis), applied through spray coating (for the desired texture). They also investigate the influence of polymer polarity and material composition on color morphing kinetics and superomniphobicity. The color morphing surfaces with effective chemical shielding can be designed with a wide variety of photochromic and thermochromic pigments and applied on a wide variety of substrates envision that such surfaces will have a wide range of applications including camouflage soldier fabrics/apparel for chem-bio warfare, color morphing soft robots, rewritable color patterns, optical data storage, and ophthalmic sun screening.

Polymer coatings as functional surfacesis that how polymer chemistry (fluorination, functional groups) and processing (coating method, drying) control interface properties. Structure–property relationships: how morphology (SEM), chemistry (FTIR), and mechanical or interfacial behaviors (contact and sliding angles) tie together to yield desired surface outcomes (e.g., low adhesion, easy shedding of liquids).

They use characterization method is FTIR, SEM, contact-angle goniometry, and UV-vis or fluorescence imaging are standard techniques taught in courses;these figures provide real-world contexts for interpreting data.

Stimuli-responsive and adaptive surfaces: photo-responsive behavior expands the discussion to smart polymers and dynamic surfaces, a growing area in polymer science with applications in antifouling, microfluidics, and biosensing.

Interactive Element

Grouped “Molecular Design – Performance Prediction Workshop” (Polymer Design-to-Property Sprint) Objective

Let students collaborate within groups to predict the thermal, mechanical, processing and interfacial properties of materials through molecular design hypotheses, fostering cross-scale thinking and data interpretation skills. Strengthen the ability to deduce from molecular structures (monomers, branching, copolymerization, end groups) to macroscopic properties (Tg, melting behavior, strength and toughness, film-forming ability).

Preparation stage (10–15 minutes)

Divide the class into groups of 4 to 6 students.Provide each group with 3 to 4 “Material Blueprint Cards”, each card describing the core characteristics of a polymer system (such as main chain rigidity, branching degree, end group orientation, crystallization tendency, compatibility, etc.) and a target application (for example, high-temperature resistant coating, transparent packaging, stretchable film, etc.).

Offer a “Design Parameter Table”: monomer selection, branching path, molecular weight range, functional group modification, potential impact of additives/fillers, etc.

Design stage (25 to 30 minutes)

Group members take turns to play the roles of “synthesis designer, characterization engineer, processing engineer, and application reviewer” to ensure coverage of perspectives. Task: Under given constraints, propose an initial polymer design and predict key performance in the target application (such as Tg, tensile strength, elongation at break, film stiffness, viscoelastic range) using 1-2 graphs or brief equations (e.g., the influence of Mw/Mn, ΔHf, Tg trends, viscoelastic indicators). Determine which characterization methods are needed to verify the predictions (such as GPC/SEC, DSC, DMA, AFM, TEM/SEM, etc.). Design output: A 2-page “design brief” including design concepts, predicted performance indicators, selected characterization methods, possible sources of experimental deviation, and a brief risk assessment.

Presentation and comparison stage (15-20 minutes)

Each group presents their design and predictions to the class in 5-7 minutes, explaining why they chose specific molecular features to achieve the target performance. Other group members act as “peer reviewers”, raising operational questions, potential side effects, and alternative designs, and offering a 1-2 sentence improvement suggestion. The teacher provides a brief comment after each group’s presentation, focusing on the “coherence of cross-scale logic, verifiability, and sensitivity analysis to actual processing conditions”.

Evaluation points

Cross-scale connections: Is the derivation from structural features to performance indicators clear and reasonable?

Matching degree of characterization strategies: Does the selected characterization method cover the key assumptions in the design?

Data-driven reasoning: Can qualitative or quantitative trends (such as Tg, Vicat, E’, MFI) and their boundary conditions be proposed?

Cooperation and communication: The effectiveness of the group collaboration process, role rotation, and clear expression in the report.

Reference

[1] P. Kantam, V. K. Manivasagam, T. K. Jammu, R. M. Sabino, S. Vallabhuneni, Y. J. Kim, A. K. Kota, K. C. Popat, Interaction of Blood and Bacteria with Slippery Hydrophilic Surfaces. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 11, 2300564. https://doi.org/10.1002/admi.202300564