39 Polymers For Biomedical Applications

mboosal and Anna AD

1. Introduction

Polymers play a foundational role in modern biomedical engineering, enabling the design of materials that interact safely and effectively with biological systems. Arising from tunable chemical structures, mechanical properties, degradation rates, and processing methods, their versatility allows them to be engineered for a wide range of clinical applications, from wound closure and tissue regeneration to drug delivery, implants, and diagnostic devices.

Biomedically relevant polymers fall into several broad categories, including synthetic degradable polymers (e.g., PLA, PGA, PCL, PDO), synthetic non-degradable polymers (e.g., polyethylene, polyurethane, PTFE), and natural polymers (e.g., collagen, hyaluronic acid, chitosan). Each class offers distinct advantages: synthetic polymers provide predictable mechanical and degradation profiles, whereas natural polymers offer inherent bioactivity and cell-interaction capabilities. The selection of a polymer for a given application requires balancing performance factors such as mechanical strength, elasticity, hydrophilicity, surface chemistry, and biocompatibility.

Smart polymers capable of responding to stimuli (pH, temperature, or enzymes) are now used in targeted drug release and adaptive implants. Hydrogels with tissue-like water content support controlled healing and cell growth, while nanofibrous scaffolds fabricated by electrospining emulate the extracellular matrix for regenerative medicine.

This chapter concludes by guiding readers toward a practical understanding of how polymer properties translate into real-world biomedical performance. By connecting fundamental concepts with emerging innovations, it provides a framework for thoughtful material selection and design that supports safe, effective, and application-specific clinical use.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the learner will be able to:

- Define major classes of biomedical polymers (synthetic degradable, synthetic non-degradable, and natural) and differentiate their key properties.

- Identify common biomedical applications that rely on polymeric materials and match appropriate polymers to each use-case.

- Compare emerging polymer technologies—such as hydrogels, smart polymers, nanofibers, and drug-eluting constructs—based on their functional advantages.

- Recognize essential polymer fabrication and processing methods.

2. Biomedical Polymer Classification

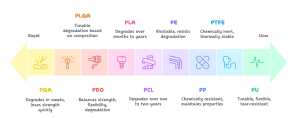

Biomedical polymers are generally categorized according to their ability to degrade within the body and their source of origin (Figure 1). In this framework, they fall into two categories of non-degradable and degradable polymers. Both degradable and non-degradable polymers can be derived from natural or synthetic sources. Degradable polymers, such as collagen or PLA, are designed to break down at controlled rates in the body, making them suitable for temporary implants, tissue engineering, or drug delivery. Non-degradable polymers, including materials like PTFE or processed silk, maintain their structural stability over time and are commonly used for long-term implants and durable biomedical devices.

Figure 1. A classification based on degradability and origin for different medical applications. The infographic is generated with NotebookLM.

2.1. Synthetic Degradable Polymers

Synthetic degradable polymers are designed to break down within the physiological environment through hydrolysis or enzymatic action, making them ideal for temporary biomedical devices. These polymers offer a range of mechanical and degradation profiles that can be tailored to match specific tissue-healing timelines.

2.1.1 Polylactic Acid (PLA)

Polylactic acid (PLA) is a widely used aliphatic polyester derived from lactic acid. It degrades slowly, often over many months or even years, due to its relatively hydrophobic backbone and semicrystalline structure. PLA exhibits high stiffness and brittleness, which makes it suitable for applications requiring prolonged mechanical support. Because of its slow degradation rate and mechanical stability, PLA is commonly used in long-lasting resorbable implants such as fixation screws, orthopedic devices, and load-bearing scaffolds in tissue engineering.

2.1.2 Polyglycolic Acid (PGA)

Polyglycolic acid (PGA), another foundational biodegradable polymer, degrades significantly faster than PLA, typically within 4 to 6 weeks. Its hydrophilic nature leads to rapid water uptake, accelerating hydrolysis and resulting in a quick decline in mechanical integrity. Although PGA provides high initial tensile strength, it loses this strength rapidly as degradation progresses. This behavior made PGA suitable for the earliest generations of absorbable sutures, although its rapid degradation limits its use in applications requiring prolonged support.

2.1.3 Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)

PLGA is a copolymer composed of lactic acid and glycolic acid units. It offers a highly tunable degradation profile because the ratio of lactic to glycolic components directly influences its mechanical properties, hydrophilicity, and hydrolysis rate. Higher glycolic content leads to faster degradation, while higher lactic content slows the process. This flexibility has made PLGA a standard biomaterial for controlled drug-delivery systems, injectable microspheres, and various tissue-engineering scaffolds where predictable degradation is critical.

2.1.4 Polycaprolactone (PCL)

Polycaprolactone (PCL) is a flexible, semicrystalline polyester characterized by slow degradation, often taking one to two years or longer. Its low glass transition temperature results in high elasticity and ductility, making it useful in situations where flexibility is required. PCL is biocompatible and highly processable, which enables fabrication through techniques such as electrospinning and melt extrusion. These characteristics make PCL valuable for reinforcing sutures, creating soft tissue scaffolds, and developing resorbable meshes.

2.1.5 Polydioxanone (PDO)

Polydioxanone (PDO) provides a balanced combination of mechanical strength, flexibility, and moderate degradation time, typically around six months. PDO maintains tensile stability significantly longer than PGA and is more flexible than PLA, giving it an ideal balance for soft-tissue approximation. Its degradation proceeds through bulk hydrolysis, producing biocompatible byproducts. Because of these favorable mechanical and degradation characteristics, PDO is widely used in absorbable monofilament sutures and barbed sutures, particularly in cosmetic, soft-tissue, and minimally invasive surgical applications.

UNIFY Barbed PDO Surgical Sutures

2.2. Synthetic Non-Degradable Polymers

Synthetic non-degradable polymers are intended to remain stable for extended periods inside the body, providing long-term durability for permanent implants and biomedical devices. These polymers resist hydrolysis, oxidation, and enzymatic degradation, making them essential in clinical applications where mechanical reliability and structural stability are required over years or even decades.

2.2.1. Polyethylene (PE)

Polyethylene (PE) is a chemically stable and highly wear-resistant polymer widely used in orthopedic and medical applications. Its ultra-high-molecular-weight form (UHMWPE) exhibits exceptional toughness, low friction, and outstanding resistance to abrasion and fatigue, which makes it the gold standard for articulating surfaces in joint replacements such as hip and knee prostheses. PE’s biostability ensures that it does not degrade under physiological conditions, while its mechanical properties support repeated loading without failure. These characteristics have established PE as a cornerstone material in long-term load-bearing implants.

2.2.2. Polypropylene (PP)

Polypropylene (PP) is another widely utilized non-degradable polymer valued for its combination of strength, low density, and resistance to chemical and environmental degradation. Its hydrophobic nature and high tensile strength make PP a preferred material for permanent sutures such as Prolene™, as well as for hernia meshes and other soft-tissue reinforcement devices. PP maintains its mechanical properties over time, does not undergo significant creep under physiological loads, and exhibits excellent fatigue resistance. These qualities allow polypropylene-based implants to remain functional and stable over the patient’s lifetime.

2.2.3. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) is renowned for its extreme chemical inertness, thermal stability, and exceptionally low coefficient of friction. These properties make PTFE suitable for vascular grafts, expanded PTFE (ePTFE) membranes, and various implantable medical devices requiring long-term biostability. PTFE does not provoke significant inflammatory reactions due to its low surface energy and non-reactive chemical structure. It resists nearly all solvents, enzymes, and physiological chemicals, allowing it to remain intact and functional for decades within the body. Because of this unmatched durability, PTFE is commonly selected for cardiovascular and reconstructive applications.

2.2.4. Polyurethane (PU)

Polyurethane (PU) represents a diverse class of elastomeric polymers with highly tunable mechanical properties, ranging from soft and flexible to tough and abrasion-resistant. This versatility enables PU to meet the mechanical demands of dynamic biomedical applications. PUs are commonly used in pacemaker leads, catheters, wound dressings, and artificial heart components because they combine flexibility, tear resistance, and biostability under continuous cyclic loading. Their microphase-separated structure contributes to excellent elasticity and long-term durability, allowing polyurethane devices to maintain performance over prolonged implantation periods.

2.2.5. Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA)

Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) is a rigid, transparent polymer widely used in orthopedic, ophthalmic, and dental applications. In bone cement, PMMA provides bulk mechanical support by anchoring prosthetic components to bone. In intraocular lenses, its optical clarity and dimensional stability are critical for long-term visual performance. PMMA also resists environmental stress cracking and maintains its properties over time, making it a reliable material for load-bearing and optical biomedical devices. Its mechanical rigidity, excellent biocompatibility, and long-term stability contribute to its widespread use in permanent implants.

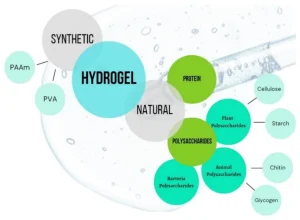

Figure 2. Polymer degradation rates range from rapid to extremely slow.(It is generated with Napkin AI)

2.3. Natural Degradable Polymers

Most natural polymers used in biomedical applications are readily degradable within the physiological environment due to the presence of specific enzymes capable of breaking down their molecular structures. These polymers typically resemble components of the native extracellular matrix, allowing them not only to support cell adhesion and signaling but also to undergo controlled biodegradation that facilitates tissue remodeling. Their breakdown products are generally non-toxic and easily metabolized, making them highly suitable for applications in wound healing, drug delivery, and regenerative medicine. The degradability of these materials enables implanted scaffolds or hydrogels to gradually transfer mechanical load to regenerating tissue while being resorbed naturally, eliminating the need for surgical removal. Although their mechanical strength is often lower than that of synthetic polymers, their ability to provide bioactive environments, promote cell infiltration, and integrate seamlessly with host tissues makes degradable natural polymers indispensable in biomedical engineering.

2.3.1. Collagen

Collagen is the predominant structural protein in the extracellular matrix, providing mechanical strength and biological cues that guide cell attachment, migration, and differentiation. Because of its native presence in connective tissues, collagen is exceptionally biocompatible and supports integration with surrounding tissues when used in medical applications. It degrades enzymatically into non-toxic byproducts and forms porous structures that facilitate nutrient transport and cell infiltration. Collagen is widely used in wound dressings, hemostatic agents, scaffolds for regenerative medicine, and surface coatings, such as collagen-modified sutures, to enhance fibroblast adhesion and promote tissue healing.

2.3.2. Gelatin

Gelatin is a denatured derivative of collagen that retains many of collagen’s bioactive sequences but offers greater ease of processing. It dissolves in aqueous solutions at mild temperatures and forms hydrogels through thermal or chemical crosslinking, making it suitable for encapsulating cells, drugs, or growth factors. Gelatin’s enzymatic degradability and tunable gelation behavior allow precise control over scaffold softness, porosity, and degradation rate. It is used in microcarriers, drug delivery matrices, injectable hydrogels, and tissue engineering constructs where mild fabrication conditions and biological compatibility are essential.

2.3.3. Hyaluronic Acid (HA)

Hyaluronic acid is a highly hydrophilic polysaccharide found naturally in connective tissues, skin, and the vitreous humor of the eye. Its exceptional ability to bind and retain water gives it a gel-like character that supports tissue lubrication, hydration, and cell migration. HA participates in wound healing, inflammation modulation, and extracellular matrix remodeling. These properties make it widely used in dermal fillers, viscosupplements for osteoarthritis treatment, wound dressings, and hydrogel coatings. In hydrogel mantle systems, such as HA–PVP coatings for sutures, HA helps maintain moisture around the wound and may reduce tissue irritation.

2.3.4. Chitosan

Chitosan is a partially deacetylated derivative of chitin, which is found in the exoskeletons of crustaceans. It has intrinsic antibacterial properties, biodegrades into non-toxic sugars, and exhibits strong mucoadhesive behavior. Chitosan’s positive charge at physiological pH allows electrostatic interactions with negatively charged biomolecules and cell membranes, contributing to hemostatic activity and enhanced wound healing. It can form films, fibers, or hydrogels, making it useful in wound dressings, drug delivery vehicles, and tissue regeneration scaffolds, particularly in environments where antimicrobial action or bioadhesion is important.

2.3.5. Fibrin

Fibrin is a natural fibrous protein formed during the blood clotting cascade. It polymerizes into a porous network that supports early stages of wound healing by guiding cell infiltration, angiogenesis, and tissue regeneration. Because fibrin is inherently bioactive and degrades through natural enzymatic pathways, it is widely used in tissue adhesives, sealants, and regenerative scaffolds. Fibrin-based matrices provide an environment that closely mimics early extracellular matrix formation, supporting rapid tissue integration and repair. Its biological activity makes it especially valuable in applications requiring enhanced healing responses.

2.4. Non-Degradable or Slowly Degradable Natural Polymers

While most natural polymers used in biomedical applications are enzymatically degradable, a subset of natural materials either degrade extremely slowly or require specialized enzymes that are not present in significant amounts in the human body. These polymers therefore behave as semi-permanent biomaterials, maintaining their structure and stability for extended periods. Their durability and mechanical robustness make them suitable for long-term implants, biomedical textiles, and device components where sustained performance is essential. However, their limited degradability means they do not remodel as quickly as other natural polymers and often require surface modification to improve cell interactions.

2.4.1. Cellulose

Cellulose is one of the most abundant natural polymers, composed of β(1→4)-linked glucose units that form highly crystalline microfibrils through extensive hydrogen bonding. Humans lack cellulase enzymes, meaning cellulose cannot be efficiently broken down within the body, which gives it exceptional long-term stability. Because of its mechanical strength, hydrophilicity, and chemical versatility, cellulose and its derivatives (such as carboxymethyl cellulose or hydroxyethyl cellulose) are widely used in wound dressings, drug-delivery films, and capsule coatings. Although inherently non-degradable in vivo, cellulose supports fluid absorption and can be chemically modified to improve bioactivity, making it a valuable material in external and implantable biomedical applications.

2.4.2. Silk Fibroin

Silk fibroin, derived from silkworm cocoons, is a protein-based natural polymer known for its remarkable tensile strength, biocompatibility, and slow biodegradation rate. The high degree of β-sheet crystallinity in silk fibroin contributes to its resistance to enzymatic breakdown, allowing it to persist in tissues for months or even years depending on processing methods. Silk has been used historically as a non-absorbable suture material and continues to serve as a scaffold material for tissue engineering, nerve regeneration, and ocular applications. Although silk is technically degradable under specific enzymatic conditions, its degradation is sufficiently slow that it behaves functionally as a long-term biomaterial.

2.4.3. Keratin

Keratin is a structural protein found in hair, nails, and wool. It contains a high content of cysteine residues, forming extensive disulfide crosslinks that contribute to its mechanical rigidity and slow biodegradation. Keratin-based biomaterials have gained attention for their intrinsic bioactivity, ability to promote cell adhesion, and potential for forming films, sponges, and hydrogels. However, degradation of keratin requires specific proteases that are not abundant in human tissues, resulting in prolonged stability when used in biomedical applications. Keratin’s combination of strength and biological affinity makes it useful in wound dressings, nerve conduits, and controlled-release systems.

2.4.4. Elastin

Elastin is a key protein in elastic tissues such as skin, lungs, and blood vessels. It provides long-term resilience and passive recoil due to its highly crosslinked structure and hydrophobic domains. In the body, elastin is exceptionally stable and degrades only through specialized enzymes such as elastases, which are present at low levels under normal physiological conditions. As a result, elastin persists for decades within tissues. In biomedical engineering, elastin and elastin-derived materials are used to create vascular grafts, skin substitutes, and elastic scaffolds. Although it does not degrade quickly, elastin offers excellent biocompatibility and mechanical properties that support long-term tissue integration.

3. Emerging Polymer Technologies Based on Functional Advantages

3.1. Hydrogels

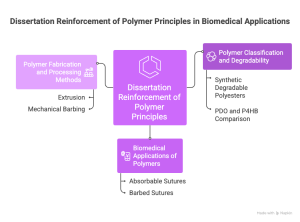

Hydrogels represent one of the most advanced classes of biomedical polymers due to their exceptionally high water content and tissue-like mechanical properties. Their ability to absorb and retain large amounts of water allows them to closely mimic the extracellular matrix, creating highly biocompatible environments conducive to cell adhesion, proliferation, and migration. Hydrogels can be engineered from both synthetic and natural polymers (Figure 3), and their crosslinking density can be tuned to control stiffness, permeability, and degradation rate. These characteristics make hydrogels ideal for wound dressings, cartilage repair, soft-tissue scaffolds, and drug-delivery depots. In situ-forming hydrogels, which polymerize directly at the target site, offer additional advantages such as minimally invasive administration and patient-specific conformability. Hydrogels can also be functionalized with bioactive molecules, peptides, or growth factors, enabling localized therapeutic effects and enhancing regenerative outcomes. Overall, their ability to create hydrated, cell-friendly microenvironments distinguishes hydrogels from other polymer technologies.

Figure 3. Type of materials used for synthesis of hydrogel based on their origin.

3.2. Smart Polymers

Smart polymers, also known as stimuli-responsive polymers, are engineered to undergo reversible changes in their structure or properties in response to environmental cues such as temperature, pH, ionic strength, light, enzymes, or electric fields. This responsiveness allows smart polymers to provide dynamic and on-demand functionality that static materials cannot achieve. For instance, thermoresponsive polymers like poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) can transition from liquid to gel at body temperature, enabling injectable scaffolds and controlled drug release triggered by physiological conditions. pH-responsive polymers are useful in tumor-targeted therapy or oral drug delivery, where acidic environments can activate release. Enzyme-responsive systems offer precise control in wound healing or tissue regeneration by degrading only in the presence of specific biological signals. The major functional advantage of smart polymers lies in their ability to interact with the biological environment in real time, adjusting their behavior to enhance therapeutic specificity, reduce side effects, and improve clinical effectiveness.

3.3. Nanofibers

Nanofibers, typically produced through electrospinning, provide unique structural advantages due to their extremely high surface-area-to-volume ratio and nanoscale architecture. Their fibrous morphology closely resembles the native extracellular matrix, allowing them to guide cellular organization, improve adhesion, and direct tissue regeneration. Nanofiber scaffolds offer exceptional control over fiber alignment, porosity, and mechanical properties, enabling applications in neural tissue engineering, wound healing, vascular grafts, and controlled drug delivery. Because individual fibers can incorporate multiple polymers or bioactive agents, nanofibrous systems can be engineered to release therapeutic compounds gradually while maintaining structural integrity. Their ability to replicate natural tissue architecture more effectively than bulk polymers or films gives nanofibers a distinct advantage in regenerative medicine, particularly when fine control over cell morphology and microenvironment is required.

3.4. Drug-Eluting Polymeric Constructs

Drug-eluting polymeric constructs integrate therapeutic agents directly within a polymer matrix to provide sustained, localized release at the site of implantation or treatment. These systems can be designed using biodegradable polymers such as PLGA, PCL, or PDO, which gradually erode to release encapsulated drugs, antibiotics, growth factors, or anti-inflammatory agents. By delivering medication directly to the targeted tissue, drug-eluting constructs reduce systemic exposure, enhance treatment efficacy, and lower the risk of adverse side effects. Their functional advantage lies in their ability to combine mechanical support with pharmacological action, making them particularly valuable in cardiovascular stents, antimicrobial sutures, orthopedic implants, and postoperative wound dressings. The controlled release kinetics can be tailored through polymer composition, molecular weight, and microstructural design, enabling precise therapeutic profiles ranging from rapid initial dosing to long-term release over months.

4. Essential Polymer Fabrication and Processing Methods

4.1. Extrusion

Extrusion is one of the most widely used polymer processing methods in biomedical engineering, particularly for creating fibers, films, and tubing. During extrusion, polymer pellets or powder are melted and forced through a die, producing continuous profiles with controlled dimensions. This method is essential for manufacturing monofilament and multifilament sutures, catheter tubing, and biodegradable scaffolds. The mechanical properties of the final construct, such as tensile strength, flexibility, and crystallinity, can be precisely tuned by adjusting process parameters like temperature, screw speed, and cooling rate. Extrusion is especially valuable for medical-grade polymers such as PDO, PLA, PCL, and polyethylene because it ensures uniformity, scalability, and reproducibility.

4.2. Injection Molding

Injection molding enables the fabrication of complex three-dimensional polymer components with high precision and excellent surface finish. In this process, molten polymer is injected into a mold cavity where it cools and solidifies into the final shape. This technique is widely used to produce orthopedic implants, dental components, medical device housings, and various single-use medical products. One of the advantages of injection molding is its ability to generate detailed geometries including threads, porous structures, and locking mechanisms that would be difficult to achieve through other methods. For biomedical applications, injection molding provides excellent dimensional control and is ideal for high-volume manufacturing of components requiring consistent mechanical performance.

4.3. Electrospinning

Electrospinning is a highly versatile technique for producing ultrafine polymer fibers with diameters ranging from nanometers to micrometers. A high-voltage electric field draws a polymer solution or melt into a continuous fiber that deposits as a nonwoven mat. Because electrospun fibers closely resemble the fibrous architecture of the extracellular matrix, they provide superior environments for cell adhesion, proliferation, and tissue remodeling. Electrospinning is widely used in regenerative medicine, wound dressings, drug delivery systems, and vascular grafts. The alignment, diameter, porosity, and mechanical properties of electrospun constructs can be controlled by modifying the electric field, collector geometry, and solution properties, making it one of the most tunable fabrication methods for biomedical polymers.

Electrospining of Polyvinylpyrrolidone

4.4. 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing

3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, allows precise fabrication of patient-specific and complex polymer structures that cannot be produced by traditional subtractive methods. Techniques such as fused deposition modeling (FDM), stereolithography (SLA), and selective laser sintering (SLS) are commonly used for biomedical applications. These methods can process a variety of polymers, including PLA, PCL, PEG-based resins, and photocurable hydrogels, enabling the creation of customized implants, anatomical models, porous scaffolds, and drug-delivery devices. The key advantage of 3D printing is its ability to integrate intricate internal architectures, gradient structures, and controlled porosity, which enhances cell infiltration, vascularization, and mechanical performance in tissue engineering.

4.5. Solvent Casting and Particulate Leaching

Solvent casting combined with particulate leaching is a widely used technique for producing porous polymer scaffolds. A polymer solution is mixed with a porogen—typically salt particles—and cast into a mold. After solvent evaporation, the porogen is dissolved, leaving behind a network of interconnected pores. This method allows precise control of pore size and porosity by selecting appropriate particle dimensions. Because porous structures are essential for nutrient transport, cell migration, and vascularization, this method is frequently used for tissue engineering scaffolds made from PLGA, PCL, and other biodegradable polymers. It can also be adapted for drug-loaded constructs by incorporating therapeutic agents into the matrix before casting.

4.6. Freeze-Drying (Lyophilization)

Freeze-drying is used to create lightweight, highly porous, sponge-like structures from polymer solutions or hydrogels. During this process, the polymer solution is frozen, and the ice crystals are removed through sublimation under vacuum, leaving a porous matrix. This technique is particularly valuable for collagen, gelatin, chitosan, and other natural polymers because it preserves their biological activity while generating interconnected pores suitable for tissue regeneration. Freeze-dried scaffolds support cell infiltration and rapid hydration, making them useful in wound dressings, nerve conduits, and soft-tissue engineering applications.

4.7. Photopolymerization

Photopolymerization uses light, typically ultraviolet or visible wavelengths, to trigger polymer crosslinking or solidification. This method is central to fabricating photocurable hydrogels, dental resins, microfluidic components, and cell-laden constructs. Photopolymerization offers spatial and temporal control over gelation, enabling precise patterning and rapid fabrication of complex geometries. Polymers such as PEG-diacrylate, gelatin-methacryloyl (GelMA), and various acrylate-based resins are commonly processed using this technique. Because photopolymerization can occur under mild conditions, it is particularly advantageous for encapsulating living cells, growth factors, or temperature-sensitive drugs.

4.8. Melt-Spinning and Fiber Drawing

Melt-spinning and fiber drawing are essential techniques for producing polymer fibers with highly controlled diameters and molecular alignment. In melt-spinning, molten polymer is extruded through a spinneret and rapidly cooled to form a filament, which may be further drawn to improve crystallinity and tensile strength. This method is fundamental to producing sutures, meshes, and high-performance biomedical textiles. Materials such as PP, PET, PLA, and PDO are frequently processed using melt-spinning due to their thermoplastic nature and ability to produce strong, consistent fibers.

5. Discussion of a Peer-Reviewed Paper

Cong, H. (2018). Studies of Barbed Surgical Sutures Associated with Materials, Anchoring Performance and Histology (Doctoral dissertation, North Carolina State University).

Available at: Proquest

5.1 Overview of the Paper

The paper Studies of Barbed Surgical Sutures Associated with Materials, Anchoring Performance and Histology investigates how polymer selection and polymer-dependent structural design influence the performance of barbed sutures in surgical wound closure. The work focuses primarily on two biodegradable synthetic polymers widely used in biomedical applications: polydioxanone (PDO) and poly-4-hydroxybutyrate (P4HB). Both materials belong to the class of synthetic degradable polyesters, yet they exhibit distinct physicochemical properties, degradation profiles, and mechanical behaviors that make them suitable for different surgical contexts. By examining how these polymers behave as monofilament barbed sutures, the study provides a detailed understanding of the relationship between polymer chemistry, device geometry, and biological performance.

The research presents a comprehensive evaluation of polymer-based suture constructs through mechanical testing, thermal and microstructural characterization, degradation studies, and in vivo assessments. Tensile testing and anchoring performance measurements reveal how the intrinsic properties of PDO and P4HB govern barb strength, tissue retention, and resistance to pull-out forces. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses describe the crystallinity and thermal transitions of each polymer, demonstrating how crystalline structure contributes to stiffness, elasticity, and long-term strength retention. Scanning electron microscopy further illustrates how polymer morphology evolves with degradation, showing changes in barb integrity and surface texture as hydrolysis proceeds. In vivo studies conducted using rodent models examine tissue response, inflammatory reaction, and the long-term integration of the suture material as it degrades.

A key finding of the study is that polymer selection is essential in determining mechanical performance and biological behavior. PDO, a moderately stiff polyester with a well-characterized six-month degradation profile, maintains barb geometry effectively during the critical healing period but gradually loses mass and strength through bulk hydrolysis. In contrast, P4HB, a more elastic and slower-degrading polymer, shows improved flexibility and higher elongation to break, enabling it to accommodate tissue motion more readily. These material-dependent characteristics strongly influence anchoring stability, degradation kinetics, and tissue reaction, demonstrating that even when two devices share the same geometry, their performance varies significantly based on polymer chemistry.

5.2 How This Paper Relates to My Chapter

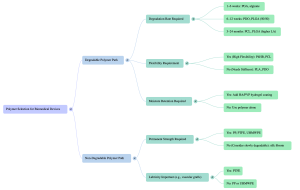

This paper directly reinforces the core themes of my chapter, which examines polymer classes, structure–property relationships, degradation behavior, biomedical applications, and emerging technologies. The study serves as a practical case example of how principles introduced in the chapter translate into a real biomedical device (Figure 5).

5.2.1. Polymer Classification and Degradability

My chapter outlines the major groups of biomedical polymers, including synthetic degradable polyesters such as PLA, PGA, PLGA, PCL, and PDO. The dissertation provides a detailed evaluation of PDO and P4HB, both members of this category, showing exactly how and why degradable polymers are used in absorbable sutures. The real-world comparison between a semi-crystalline polymer with moderate stiffness (PDO) and a more elastic slow-degrading polymer (P4HB) illustrates how chemical structure, crystallinity, and hydrophobicity determine degradation timelines and mechanical strength retention.

5.2.2. Biomedical Applications of Polymers

Absorbable sutures are a key biomedical application described in my chapter under degradable polymer use-cases. The paper expands this application by evaluating barbed sutures, an advanced polymer device designed to eliminate knot tying and improve tissue approximation. The study shows how P4HB and PDO meet the clinical requirements outlined in the chapter, such as temporary mechanical support, predictable degradation, safe byproducts, and acceptable biocompatibility. The work also highlights how design and polymer selection must be integrated, as altering barb geometry without considering polymer elasticity or brittleness may lead to failure.

5.2.3. Polymer Fabrication and Processing Methods

My chapter discusses extrusion, thermal processing, and post-fabrication modifications as essential polymer processing techniques. The paper provides an applied example: both PDO and P4HB sutures are extruded monofilaments subjected to mechanical barbing, a process that introduces localized stress concentrations influenced by polymer strength and flexibility. This connection shows how fabrication techniques determine device performance and must be matched to polymer properties.

Figure 4. Dissertation Reinforcement of Polymer Principles in Biomedical Applications (It is generated by Napkin AI)

5.3. How My Chapter Contributes Back to Understanding the Paper

While the paper focuses on a specialized application, barbed sutures, it does not elaborate extensively on the broader theoretical polymer science underpinning its findings. My chapter provides this necessary conceptual framework. By reviewing polymer classifications, degradation pathways, and processing methods, the chapter equips the reader to understand why PDO and P4HB behave differently and how their molecular structures contribute to performance differences. Additionally, the chapter’s coverage of emerging polymer technologies offers context for how barbed sutures may evolve, such as by incorporating hydrogels, bioactive coatings, or drug-eluting features. Thus, the chapter situates the dissertation within the larger field of polymer-based biomedical innovation.

6.1 Interactive Decision-Tree: Choose the Right Polymer

6.2. Case Study: Selecting a Polymer for a Next-Generation Suture

Problem: You must design a suture for cosmetic facial surgery that requires: Flexibility, Moderate strength retention for 8–10 weeks, Minimal scarring, Low inflammation, Smooth handling, Option for moisture-retentive coating. Which polymer system do you choose? Why?

Correct/Ideal Answer:

A PCL–PDO blended core, coated with HA–PVP hydrogel.

Reasoning:

- PDO → provides early strength

- PCL → adds long-term flexibility and slow degradation

- HA–PVP → improves tissue hydration and reduces irritation

- The combination balances stiffness, elasticity, and biocompatibility

Reference:

- Shastri, V. Prasad. “Non-degradable biocompatible polymers in medicine: past, present and future.” Current pharmaceutical biotechnology 4 5 (2003): 331-7 .

- Damodaran, Vinod B. et al. “Biomedical Polymers: An Overview.” (2016).

- Satchanska, Galina, Slavena Davidova, and Petar D. Petrov. “Natural and synthetic polymers for biomedical and environmental applications.” Polymers 16.8 (2024): 1159.

- Chelu, Mariana, and Adina Magdalena Musuc. “Polymer gels: Classification and recent developments in biomedical applications.” Gels 9.2 (2023): 161.

- Anderson, J. M., and D. F. Gibbons. “The new generation of biomedical polymers.” Biomaterials, Medical Devices, and Artificial Organs 2.3 (1974): 235-248.

- Malinova, Violeta, and Wolfgang Meier. “Polymer materials for biomedical applications.” (2010).

- Barar J, Aghanejad A, Fathi M, Omidi Y. Advanced drug delivery and targeting technologies for the ocular diseases. BioImpacts BI. 2016;6(1):49-67. doi:10.15171/bi.2016.07

- Patel, Vinay Kumar, et al., eds. Trends in fabrication of polymers and polymer composites. Melville, New York: AIP Publishing, 2022.

- Subramanian, Muralisrinivasan. Basics of polymers: fabrication and processing technology. Momentum Press, 2015.

- Samal, Sangram Keshari, et al. “Smart polymer hydrogels: properties, synthesis and applications.” Smart polymers and their applications. Woodhead Publishing, 2014. 237-270.

- Wang, Kaojin, et al. “Advanced functional polymer materials.” Materials Chemistry Frontiers 4.7 (2020): 1803-1915.