8 Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (ATRP): Principles and Practice

Introduction

The late twentieth century witnessed a transformative effort in polymer science: the quest to synthesize complex macromolecules with predefined dimensions and specialized functions using the versatility of free radical chemistry. While conventional Free Radical Polymerization (FRP) is highly efficient and widely applicable to diverse monomers, solvents, and reaction conditions, it critically lacks the precision required for advanced materials. The realization of controlled polymer growth—specifically, the ability to pre-determine molecular weight, composition, and architecture—is essential for developing the next generation of polymeric materials. Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (ATRP), developed in the mid-1990s, successfully answered this challenge, emerging as a cornerstone technique within controlled radical polymerization (CRP) by providing unprecedented control over polymer synthesis.

Prior to the introduction of CRP methods like ATRP, conventional FRP suffered from critical drawbacks, offering little control over the rate of reaction, stereochemistry, polydispersity (PDI) of the resulting polymer, branching, or end-group functionality. Synthesizing polymers with narrow polydispersity and specific architectures using free radical chemistry alone was incredibly difficult. ATRP overcomes these fundamental limitations through a unique mechanism that relies on the principles of Atom Transfer Radical Addition (ATRA). This system employs a transition metal complex to mediate the reversible activation and deactivation of growing free radicals. The process involves a redox reaction between an alkyl halide (the initiator/dormant chain end) and a metal catalyst, which cleaves the carbon-halogen (R-X) bond to generate a reactive free radical species. This radical then reacts with monomer units, initiating propagation. Crucially, the system maintains the concentration of active radicals approximately six orders of magnitude lower than the concentration of dormant chains. This mechanism effectively discourages uncontrolled bimolecular termination reactions, thereby facilitating controlled polymer growth. By adjusting the concentration of the metal catalyst and the reaction temperature, the polymerization reaction can be temporarily stopped or held dormant. This high degree of control allows for flexibility in the choice of end groups and enables the creation of complicated covalently bound polymer architectures, such as block copolymers. Furthermore, ATRP demonstrates unique applicability to a wide range of monomers, including polar monomers like acrylates and methacrylates. Despite its versatility and precision, a primary constraint of ATRP is the utilization of a metal catalyst system, such as those based on copper(I)/(II), ruthenium(II)/(III), or iron(II)/(III). These remaining metal ions must be removed after polymerization, which restricts certain end-use applications, particularly in biomedicine. Consequently, significant research is focused on developing “greener” ATRP methods, including reducing catalyst loading to parts per million (ppm) levels and exploring more biocompatible iron systems or metal-free options.

This section will provide a detailed understanding of Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization, establishing its role as an indispensable tool in modern polymer synthesis. We will begin by elucidating the fundamental mechanism of ATRP, focusing on the reversible deactivation, initiation, and propagation steps driven by the transition metal redox cycle. We will then analyze the critical components of the ATRP system, including the requirements for a suitable transition metal catalyst—specifically, accessible consecutive oxidation states (e.g., 2+/3+)—the role of various ligands (such as SaBOX, Me6TREN, and PMDETA) in modifying equilibrium and lowering reaction temperature, and the selection of an effective labile halogen source (e.g., bromine versus chlorine). Following this, the section will explore the applicability of ATRP to diverse monomer families, examining the polymerization of styrenes and substituted styrenes (including challenges related to cationic propagation at low temperatures) and the effective synthesis of protected acrylates and methacrylates for block copolymer formation. We will also examine the essential characterization methods for ATRP polymers, including the use of Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to determine molecular weight (Mn) and molar mass distribution, H1 NMR to verify end-group functionality and chain structure, and FTIR for functional group analysis. Finally, we will conclude by reviewing advanced applications in material science, such as polymer bioconjugates and functionalized nanogels, alongside a discussion of current challenges and the ongoing development of greener ATRP methods.

Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization Mechanism

The main principle of ATRP comes from an extension of Atom transfer radical addition (ATRA). Which uses a redox reaction between an alkyl halide and a metal complex as a catalyst to cleave the carbon to halogen (R-X) bond generating a free radical species. This reactive species is then free to react with other functionality to mediate the stepwise addition of another molecule. This principle can be applied to free radical polymerization where the generated radical reacts with the alkene functionality of a monomer and initiates a growing monomer chain. By adjusting the concentration of the catalyst and the reaction temperature the reaction can be temporarily stopped, or held dormant. By using a catalyst system, this allowed for unprecedented control over the polymerization reaction and paved the way for more specificity and advancements within controlled radical polymerization.

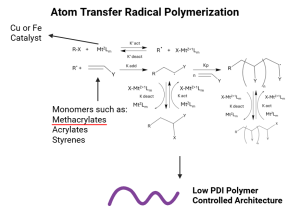

Figure 1. Mechanism of ATRP synthesis showcasing the reversible deactivation, initiation, propagation, and termination.1,6

As with any radical polymerization, Atom transfer radical polymerization follows three basic mechanistic steps: initiation, propagation and termination. The initiation step begins with the metal complex cleaving the carbon halogen, forming the radical species that forms the end of the growing chain. The metal changes oxidation state, and forms a new complex with the halogen. The formed radical reacts with a monomer to form the propagating chain. From here reversible termination can occur, where the radical reacts with the metal complex again to replace the halogen on the growing chain and deactivate the chain. The ratio of propagation rate (kₚ) to termination rate (kₜ) determines the control over polymerization. A higher kₚ/kₜ ratio favors controlled polymer growth. Generally the concentration of active radicals is about 6 orders of magnitude lower than concentration of dormant chains, this discourages bimolecular radical reactions.1,2 Activation towards propagation is dependent on the equilibrium values of the transition metal complex, solvent and temperature. Termination is reversible in the majority of cases due to the high control.

ATRP Conditions and Monomers

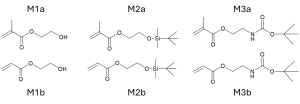

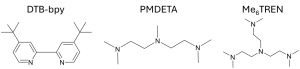

The transition metal catalyst system is the backbone of the ATRP process. In choosing a catalyst several factors must be considered. The process of ATRP relies on the redox exchange between the metal catalyst and a halogen to generate a free radical. This process must happen efficiently and be able to be controlled through changes in temperature or other factors. A suitable metal catalyst for ATRP must have accessible consecutive oxidation states (e.g. 2+/3+) to allow for switching between dormant and active states of the radical with the exchange of the halogen atom. For this state availability copper(Cu(I)/(II)) is favored as well as Ruthenium(Ru(II)/(III)) and Iron (Fe(II)/(III)), as well as nickel and rhodium based systems.6 Although Ni and Rh catalyst systems tend to have less controlled redox activity and tend to produce polymer with higher polydispersity.5 Compatibility with a variety of ligands for solubility in solutions is another important consideration, Iron and Ruthenium based catalysts tend to require more specific nitrogen containing ligands and reaction conditions, copper based catalysts readily coordinate to a variety of amine functionality which makes them more versatile and tolerant to different reaction conditions and systems. Ligands can also be used in modification of the equilibrium of the dormant and active species. Use of SaBOX ligands and a copper catalyst system was shown to dramatically reduce the temperature of polymerization of styrene by ATRP. by using a suitable ligand polystyrene with high stereoregularity and low polydispersity was formed at 30°-40° C. typical ATRP processes with a copper catalyst and PMDETA ligand proceeds at around 90° C and up to 110°-130°.4,6 This highlights the impact that ligand selection can have in the polymerization process.

The mechanism for initiation of ATRP relies on a labile halogen source, usually a substituted alkyl halide. While both bromine and chlorine have been shown to be effective halogen sources bromine tends to be preferred due to its increased reactivity. Chlorides, although effective, tend to have lower initiating efficiency and produce polymer with a larger polydispersity.3 A higher degree of alkyl substitution on the halogen carbon tends to increase initiator efficiency due to increased stabilization of the formed radical.

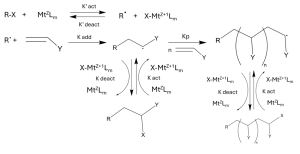

Styrene, one of the most versatile polymers in terms of polymerization techniques, undergoes ATRP effectively. Styrene commercially utilizes free radical polymerization, but ATRP allows for better control over the polymer. However, the best conditions to control this polymerization are always attempted to be improved upon. One of the required parameters for polystyrene is that it is typically done at higher temperatures (above 80°C) to get a satisfactory level of propagation.4 While 80-90°C conditions can be maintained by using a catalyst such as CuBr/PMDETA, this only works for styrene and its monomers that have electron withdrawing groups, styrene monomers with electron donating groups are left in need of a better method.4 For example, one styrene monomer, 4-MeOSt, has difficulty undergoing traditional ATRP conditions and exhibits low controllability, low molecular weight (produced oligomers), and often experiences cationic propagation of the dormant species through the C-Br or the oxidation of Cu(II) in the catalyst.4 Looking at other monomers, such as acrylates and methacrylates, lower temperature ATRP polymerization has been achieved with an additional benefit of greater control over the stereospecificity.4 A lower temperature for polymerization is beneficial in that it helps reduces the efficiency of chain transfer, thermal crosslinking, and side chain reactions of the monomers.4 Lower temperature ATRP polymerization is achievable through active SaBOX ligands (notably contains two oxazoline rings) and it was reported that higher syndiotacticity and molecular weight also occurred in the 4-MeOSt polymer (Figure 2).4 The results were promising, with a high conversion of 72% of the 4-MeOSt monomer utilizing EBPA as the initiator with L5b at only 60°C, however using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and 1H NMR, it was found that this polymerization occurred through cationic polymerization by examining the absence of peaks that should correlate to bromo-terminated polymer chains.4 The experiment looked at varying temperatures, and as the temperature of the reaction lowered to around 0°C, cationic polymerization basically completely stopped and the polymer chains formed occurred through ATRP. While the monomer conversion percent lowered as the temperature lowered, it was still concluded that ATRP of styrene could be effectively done at up -30°C with improved syndiotacticity (rr value up to 62%).4

Figure 2. 4-MeOSt and L5b (an SaBOX ligand) used in the study on low temperature polymerization of styrene and styrene monomers.4

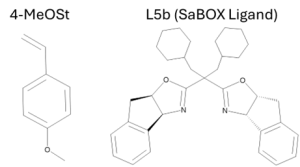

Acrylates and methacrylates are not viable for block copolymerization through anionic methods due to their polar nature. However, free radical polymerization does not have this same issue, and after the development of controlled free radical polymerization methods such as ATRP, block polymerization could occur in acrylates and methacrylates.9 However, due to the poor solubility of the monomers 2-hydroxyethyl acrylate (HEA) and 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) in non-polar solvents, the monomers are often polymerized in a protected form.9 In this case, tert-butyldimethylsilyl(TBDMS) was used to protect the hydroxy functional group present in the acrylate and methacrylate monomers (Figure 3).9 As an example of the ATRP process, M2b was polymerized in bulk under concentration ratios of [M]:[I]:[CuBr]:[L]=100:1:1:2, with EBrP and CuBr as the initiator and catalyst respectively.9 The various ligands used in testing are listed in Figure 4. Both Me6TREN and PMDETA allowed the polymerization of M2b and M3a to occur rapidly and create polymers with a narrow polydispersity index, only taking 10 mins for Me6TREN but 1-3 hours for PMDETA.9 Timing is crucial when discussing free radical polymerization, and while 10 minutes seems ideal, this is rather fast to be controllable, thus PMDETA was determined to be the chosen ligand for the continued experiments of M2b.9 Following the polymerization in each of these experiments, the polymer must be deprotected and modified post polymerization. Another experiment however, used a halogen terminated polystyrene as a macroinitiator and created block copolymers with M2b, M3b, M2a, and M3a.9 Overall, the ATRP of acrylates was proven to be effective using the two protected acrylates and two protected methacrylates (M2b, M3b, M2a, M3b) and allowed for high control of molecular weight and its distribution.9

Figure 3. Monomers (M1) used in ATRP for methacrylates (a) and acrylates (b) with their respective hydroxyl group protected shown in M2a, M2b, M3a, and M3b. These delineations change from M to P when macroinitiated by Pst.9

Figure 4. Example ligands used in the ATRP of methacrylates and acrylates.9

ATRP Characterization

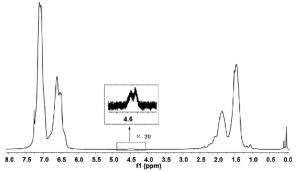

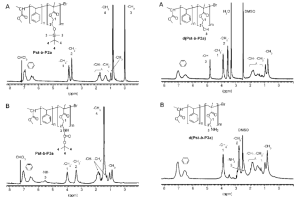

Most commonly 1H NMR is used for characterizing polymers by determining the functional groups present in a polymer chain and 1H NMR can give clues on how the reaction proceeds.5,10 This is crucial for block copolymers or figuring out if ATRP was the polymerization method. In the polymerization of styrene and styrene monomers, 1H NMR was used to check for bromo-terminated chains, as in ATRP a halogen terminated chain is characteristic.5 This was noted at the indicated range of around 4.6ppm in Figure 5. Further, 1H NMR (Figure 6) was used in the preparation of a block copolymer using polystyrene as a macroinitiator with methacrylates and acrylates depicted in Figure 3. These spectra confirmed the block polymerization in both their protected and deprotected forms.

Figure 5. 1H NMR spectrum (CDCl3, 25°C) for polystyrene with a low polymerization degree.4

Figure 6. 1H NMR spectra for protected (left) and deprotected (right) methacrylates (Pst-b-P2a and Pst-b-P3a) in CDCl3 and DMSO respectively, that have been macroinitiated by polystyrene.9

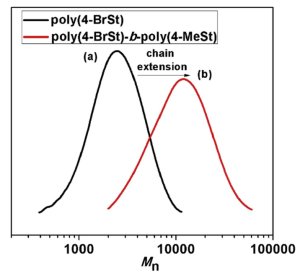

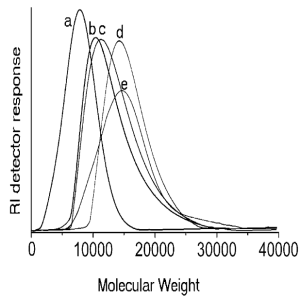

GPC or gel permeation chromatography can also be used in characterization of polymers but used to determine number average molecular weight (Mn) as shown in Figure 7 which depicts styrene monomers after polymerization. This is achieved by essentially filtering the polymer through a column which contains pores inside of beads. While the polymer travels through the column, the smaller chains get stuck and travel inside of the pores, while the larger chains are able to pass through as they are too large to get stuck in the pores. This allows for large chains to pass through faster than smaller chains and measurement of this separation determines the Mn of the chains. GPC was used, as mentioned, in determining the Mn of substituted polystyrene but also in determining the molar mass distribution of polystyrene macro-initiated block copolymers with methacrylates and acrylates (Figure 8).9

Figure 7. GPC of (a) poly(4-BrSt) homopolymer and (b) block copolymer poly(4-BrSt)-b-poly(4-MeSt).4

Figure 7. GPC of (a) poly(4-BrSt) homopolymer and (b) block copolymer poly(4-BrSt)-b-poly(4-MeSt).4

Figure 8. Molar mass distribution of macroinitiator and the block copolymers determined by GPC; (a) Pst; (b) Pst-b-P2a; (c) Pst-b-P2b; (d) Pst-b-P3a; (e) Pst-b-P3b.9

Figure 8. Molar mass distribution of macroinitiator and the block copolymers determined by GPC; (a) Pst; (b) Pst-b-P2a; (c) Pst-b-P2b; (d) Pst-b-P3a; (e) Pst-b-P3b.9

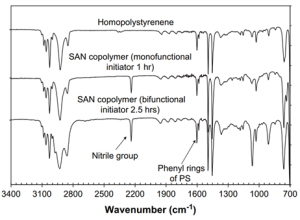

FTIR is also another characterization method for evaluating polymerization and can be advantageous in ATRP that create or destroy functional groups. As shown in Figure 9, the nitrile group appears in the spectra of the copolymer groups that contain acrylonitrile, but not in the homopolystyrene spectrum.10 While this can be beneficial, it is not the most common form of characterization as some monomers may not experience a change in functional groups after polymerization.

Figure 9. FTIR spectra of homopolystyrene and two SAN copolymers that have different ratios of acrylonitrile.10

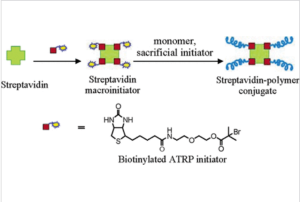

ATRP can produce incredibly uniform polymers of incredibly narrow polydispersity. There is also the potential to use ATRP to construct complicated and specific polymer architectures, which can be carefully tailored to a variety of applications. For its high level of precision and specificity ATRP is uniquely suited to biomedical applications. One example is protein grafting with ATRP to make polymer bioconjugates. Polymer bioconjugates are used in biomedical applications for drug delivery, or to extend the life of certain protein complexes which are unstable inside the body. In this study the protein Streptividin was successfully grafted with polymer to create a temperature sensitive bioconjugated complex.

Figure 10. Diagram of mechanism of grafting on to streptavidin protein to create bioconjugated complex.12

Due to ATRP’s tolerance of many functional groups the study anticipates that this process can be done with a variety of proteins and pharmaceuticals. This is a one step process that has the potential to be scaled up for industrial production.11 In grafting from processes like these there is the additional possibility of adding functionality to the other end of the grafted chain, in order to attach to a specified receptor or cell membrane before release which could make ATRP a simple method to encase drugs for targeted therapy.12

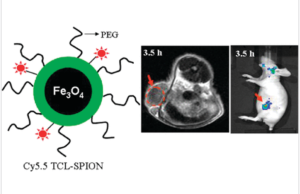

ATRP can be used in the formation and functionalization of polymer nanogels. Currently nanocrystals are being investigated for use in in-vivo diagnostic medicine and cell imaging applications. Many of these nanocrystals and nanogel materials are not water soluble or have low affinity for protic solvents. ATRP made polymers have been used to solubilize these nanomaterials as well as impart additional functionality to nanoparticles. In study ATRP was used to make coatings for magnetite, and iron oxide nanoparticles for the purpose of tumor detection in vivo. The nanoparticles were found effectively accumulating at the tumor site in mice, without the use of any additional targeting ligands.13

Figure 11. Diagram of the iron oxide nanoparticles, and MRI imaging of accumulation of nanoparticles at tumor site in mice.13

While ATRP has many promising applications in the biomedical field, the process presents one large drawback. The use of transition metal catalysts in the formation of polymer bioconjugates limits their potential applications unless these metals can be effectively removed from the formed polymer after polymerization. To mitigate this risk, greener methods of ATRP are under development. Successful polymerization of styrene at very low catalyst loading, ligands with scaffolds of highly electron donating groups were used to increase the functionality of the copper catalysts so effective polymerization could occur at concentrations as low as 10 ppm of catalyst.14 Additionally, iron catalysts have been explored as a more biocompatible option, and newer metal free catalyst options are in development although they currently have not shown enough redox activity to be a suitable replacement for metal catalysts.14

Since its development Atom Transfer radical polymerization has emerged as one of the more versatile and powerful techniques for controlled radical polymerization. Due to its precise use of a transition metal redox couple to activate and deactivate growing chains It provides unprecedented control over polymer molecular weight, composition, and covalent architecture of polymers. It is an invaluable technique to aid in new developments in material science and biotechnology. This chapter highlighted the critical factors in the mechanism and characterization of polymers formed through ATRP, as well as technological advances and applications of this technique. Despite its many advantages, challenges still remain in terms of efficiency, scalability, and the larger environmental impact of this system. Ongoing research is focused on minimizing the use of toxic reagents, improving the stability of catalysts in milder conditions, and expanding the scope of ATRP to new applications. Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization is a cornerstone of controlled radical polymerization techniques, and remains essential to developing the next generation of polymeric materials.

Overview of Oxygen-Driven Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization16

Oxygen-Driven Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (ATRP) is a contemporary controlled radical polymerization (CRP) technique that addresses a major operational challenge of conventional ATRP by intentionally incorporating oxygen as a required co-factor to promote the reaction. Conventional ATRP, developed in the mid-1990s, fundamentally transformed polymer science by successfully achieving the goal of synthesizing complex macromolecules with predefined characteristics, something traditional Free Radical Polymerization (FRP) could not accomplish.

The Oxygen Constraint in Conventional ATRP

The mechanism of ATRP, detailed in this chapter, relies on a transition metal complex (such as copper(I)/(II)) mediating the reversible activation and deactivation of growing free radicals. This reversible process maintains the concentration of active radicals significantly lower than dormant chains, which minimizes uncontrolled termination and ensures high control over molecular weight, composition, and architecture.

However, the precision outlined traditionally comes with a severe practical constraint: the absolute necessity of excluding oxygen. Oxygen molecules present a significant challenge in conventional radical polymerization because they quickly quench active radical species, halting the polymerization process. Furthermore, oxygen rapidly oxidizes the lower-valent transition metal catalyst (e.g., Cu(I)) to its higher-valent state (Cu(II)), thereby compromising the catalyst’s ability to activate alkyl halides and propagate polymerization. Consequently, traditional ATRP requires labor-intensive methods such as freeze-pump-thaw cycles or nitrogen bubbling to eliminate oxygen, procedures that pose operational challenges and restrict applications.

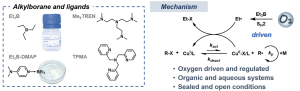

Scheme 1. Scheme of Oxygen-Driven ATRP.16

The Oxygen-Driven Mechanism and System Components

The oxygen-driven approach is designed to circumvent the need for stringent oxygen removal by utilizing specific alkylborane compounds, such as triethylborane (Et3B) or the air-stable triethylborane-amine complex (Et3B-DMAP).

The proposed mechanism leverages the autoxidation properties of alkylborane compounds. The autoxidation of Et3B and oxygen generates ethyl radicals (Et⋅), which serve a dual purpose: they initiate ATRP and, more critically, drive the reducing/reactivating cycle. This process is analogous to Initiators for Continuous Activator Regeneration (ICAR)-ATRP. The generated ethyl radicals continuously reduce the deactivated higher-valent copper catalyst (CuBr2) back to the active Cu(I) species. This constant regeneration replenishes any Cu(I) lost due to radical termination or oxidation by the ambient oxygen, ensuring sustained polymerization control. Due to this crucial mediation role, the system is accurately termed “oxygen-driven,” as oxygen initiates the process and mediates the entire reaction.

Operational Versatility and Performance

This oxygen-driven ATRP is highly robust, demonstrating compatibility across a broad range of monomers, including various (meth)acrylates, in both organic and aqueous solvents. It has been successfully conducted in both sealed systems containing ambient air and in unsealed, open-to-air conditions.

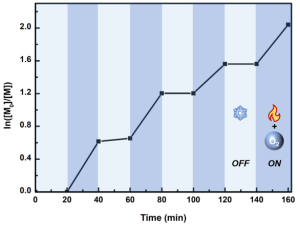

To maximize safety and simplify open-air use, the air-stable Et3B-DMAP complex was introduced. This complex can be safely stored in ambient air; when heated (typically to around 60°C), the coordination bond breaks, continuously releasing Et3B to enable open-to-air controlled radical polymerization. Using this technique, researchers achieved well-defined polymers with narrow molecular weight distributions (PDI as low as 1.11) and number-average molecular weights (Mn) consistent with theoretical values, confirming that the controlled polymerization mechanism described in this chapter is fully operational under aerobic conditions. Furthermore, precise control over polymerization can be demonstrated through “on/off” heating cycles, providing temporal control over chain growth.

Figure 12. Temporal control of polymerization with on/off heating switching.16

Relationship to This Chapter: Addressing Practical Constraints and Advancing Applications

The oxygen-driven ATRP technique relates directly to the foundational principles and future goals outlined in this chapter by providing a critical advancement that makes controlled polymerization more practical and widely applicable.

The foundation of ATRP, as detailed in this chapter, is its ability to produce polymers with predetermined molecular weight and narrow dispersity using the transition metal redox cycle. The oxygen-driven method retains this precision while eliminating, oxygen sensitivity as a hurdle, making the technology simpler and more scalable.

The oxygen-driven approach aligns with the “greener” ATRP methods by enabling controlled polymerization in aqueous media, which is essential for synthesizing complex structures like protein–polymer conjugates under aerobic conditions.

Test your knowledge on ATRP!

Works Cited

(1)

Hasirci, V.; Yilgor, P.; Endogan, T.; Eke, G.; Hasirci, N. 1.121 – Polymer Fundamentals: Polymer Synthesis. In Comprehensive Biomaterials; Ducheyne, P., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2011; pp 349–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-055294-1.00034-9.

(2)

University, C. M. Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization – Matyjaszewski Polymer Group – Carnegie Mellon University. http://www.cmu.edu/maty/chem/fundamentals-atrp/atrp.html (accessed 2024-11-10).

(3)

Wang, J.-S.; Matyjaszewski, K. Controlled/”Living” Radical Polymerization. Halogen Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization Promoted by a Cu(I)/Cu(II) Redox Process. Macromolecules 1995, 28 (23), 7901–7910. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma00127a042.

(4)

Wang, X.-Y.; Chen, Z.-H.; Sun, X.-L.; Tang, Y. Low Temperature Effect on ATRP of Styrene and Substituted Styrenes Enabled by SaBOX Ligand. Polymer 2019, 178, 121630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2019.121630.

(5)

Gibson, V. C.; Marshall, E. L. Metal Complexes as Catalysts for Polymerization Reactions. In Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II; Elsevier, 2003; pp 1–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043748-6/09010-1.

(6)

Metal Complexes as Catalysts for Polymerization Reactions – ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B0080437486090101 (accessed 2024-11-10).

(7)

Duque Sánchez, L.; Brack, N.; Postma, A.; Pigram, P. J.; Meagher, L. Surface Modification of Electrospun Fibres for Biomedical Applications: A Focus on Radical Polymerization Methods. Biomaterials 2016, 106, 24–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.08.011.

(8)

Chen, G.; Zhu, X.; Cheng, Z.; Lu, J. Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(Vinyl Chloride-Co-Vinyl Acetate)-Graft-Poly[(Meth)Acrylates] by Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2005, 96 (1), 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.21394.

(9)

Yin, M.; Habicher, W. D.; Voit, B. Preparation of Functional Poly(Acrylates and Methacrylates) and Block Copolymers Formation Based on Polystyrene Macroinitiator by ATRP. Polymer 2005, 46 (10), 3215–3222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2005.03.005.

(10)

Al-Harthi, M.; Sardashti, A.; Soares, J. B. P.; Simon, L. C. Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (ATRP) of Styrene and Acrylonitrile with Monofunctional and Bifunctional Initiators. Polymer 2007, 48 (7), 1954–1961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2007.01.052.

(11)

Siegwart, D. J.; Oh, J. K.; Matyjaszewski, K. ATRP in the Design of Functional Materials for Biomedical Applications. Progress in Polymer Science 2012, 37 (1), 18–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.08.001.

(12)

Bontempo, D.; Maynard, H. D. Streptavidin as a Macroinitiator for Polymerization: In Situ Protein−Polymer Conjugate Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127 (18), 6508–6509. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja042230+.

(13)

Lee, H.; Yu, M. K.; Park, S.; Moon, S.; Min, J. J.; Jeong, Y. Y.; Kang, H.-W.; Jon, S. Thermally Cross-Linked Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Application as a Dual Imaging Probe for Cancer in Vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129 (42), 12739–12745. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja072210i.

(14)

Dworakowska, S.; Lorandi, F.; Gorczyński, A.; Matyjaszewski, K. Toward Green Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization: Current Status and Future Challenges. Advanced Science 2022, 9 (19), 2106076. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202106076.

(15)

Odian, G. Principles of Polymerization; Wiley, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1002/047147875X.

(16)

Du, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xie, Z.; Yi, S.; Matyjaszewski, K.; Pan, X. Oxygen-Driven Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147 (4), 3662–3669. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c15952.