29 Electrospinning of Polymer Nanofibers: Principles, Advances, and Emerging Applications

Haoyuan Bai

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, students will be able to:

- Explain the electrohydrodynamic mechanisms underlying electrospinning.

- Predict how solution and processing parameters influence fiber morphology and quality.

- Describe structure–property relationships specific to electrospun polymer nanofibers.

- Compare advanced electrospinning techniques and identify their advantages.

- Evaluate emerging applications of electrospun nanofibers in energy, biomedicine, and electronics.

- Interpret and critique a peer-reviewed electrospinning research paper using the PSP framework.

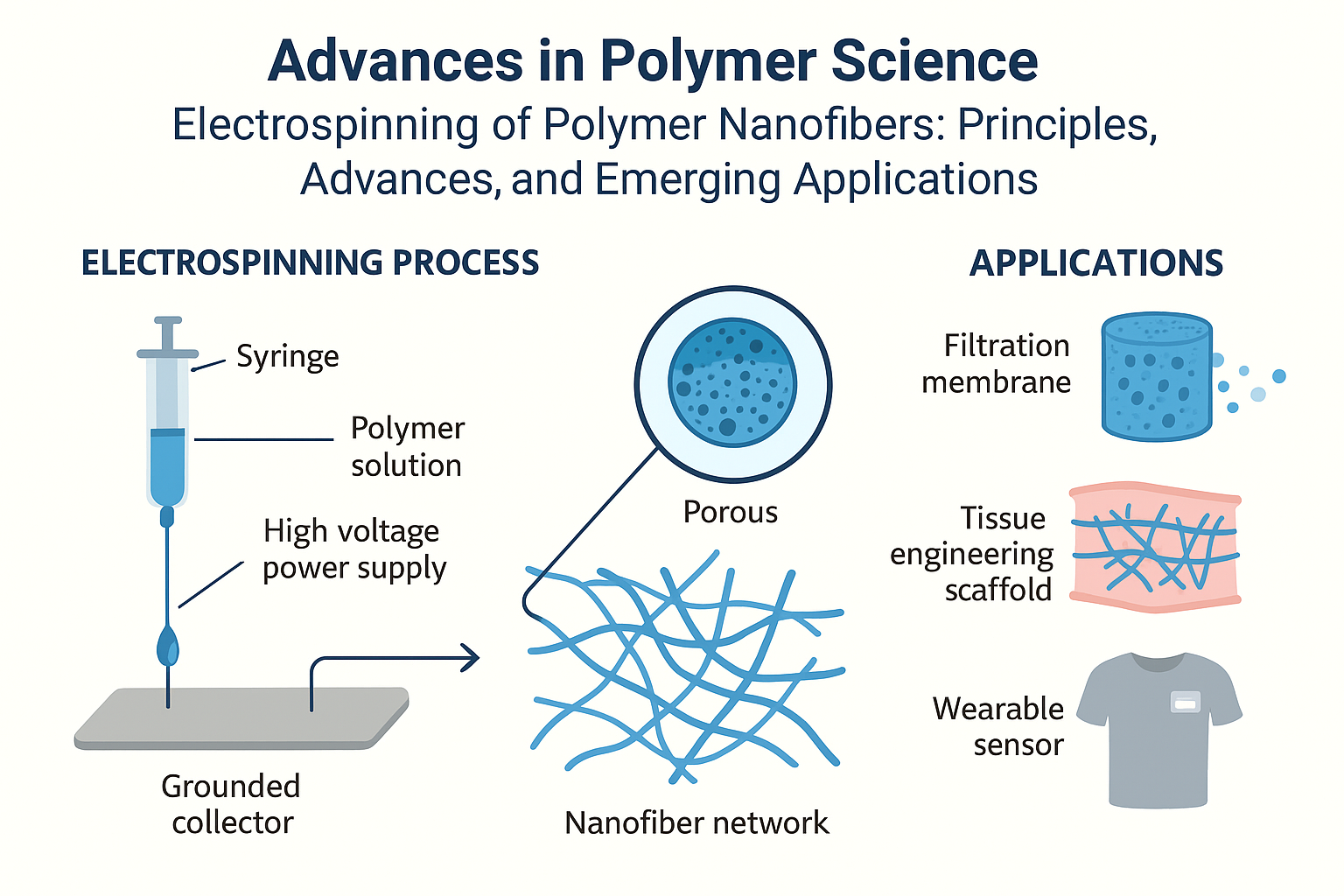

1. Introduction to the Topic

Electrospinning is a versatile and widely studied fiber‐forming technique capable of producing polymer nanofibers with diameters ranging from several micrometers down to below 50 nm. Unlike conventional melt or solution spinning methods that rely primarily on mechanical drawing, electrospinning uses a high-voltage electric field to initiate and elongate a polymer jet. The intrinsic coupling of electrohydrodynamic forces, polymer viscoelasticity, solvent evaporation, and environmental conditions leads to a unique processing pathway that is exceptionally sensitive to tunable parameters. As a result, electrospinning offers unparalleled control over fiber diameter, morphology, porosity, and alignment.

Over the past two decades, electrospinning has evolved from a laboratory curiosity into a powerful platform for advanced materials development. Electrospun nanofibers exhibit high specific surface area, interconnected porous networks, tunable mechanical anisotropy, and the ability to host multifunctional fillers, drugs, electrolytes, or biological molecules. These attributes enable a wide range of emerging applications in energy storage, tissue engineering, wound care, flexible electronics, environmental remediation, and wearable sensing technologies. At the same time, new variations of the classical setup—such as coaxial, triaxial, needleless, near-field, and melt electrospinning—have expanded the technique into scalable manufacturing and micro-structured patterning.

This chapter provides a comprehensive overview of the principles of electrospinning, the key processing parameters that govern fiber formation, and the underlying structure–property relationships that link processing with performance. It also surveys major technological advances in electrospinning and highlights rapidly developing application areas. A peer-reviewed research paper is incorporated to demonstrate how real-world studies apply the processing–structure–property (PSP) framework in the design of functional electrospun materials. This chapter aims to equip graduate students with a mechanistic understanding of electrospinning and provide a foundation for critically evaluating current and emerging research in polymer nanofiber fabrication.

2. Fundamentals of Electrospinning

Electrospinning is an electrohydrodynamic fiber‐forming technique capable of producing polymer fibers with diameters ranging from several micrometers down to tens of nanometers. The fundamental mechanism couples electrostatic forces, fluid dynamics, viscoelasticity, and solvent evaporation, making it distinct from traditional spinning processes such as melt spinning or solution wet spinning. This section provides a comprehensive overview of the principles governing electrospinning, emphasizing the relationships among solution properties, processing parameters, jet instability, and fiber morphology.

2.1 Electrohydrodynamic Theory: From Droplet to Nanofiber

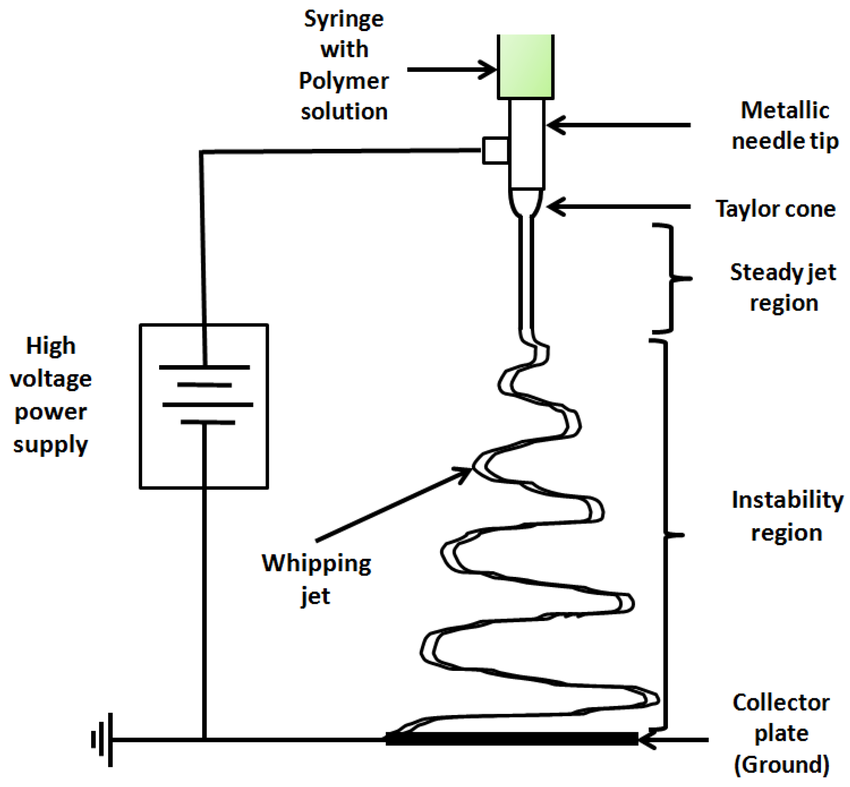

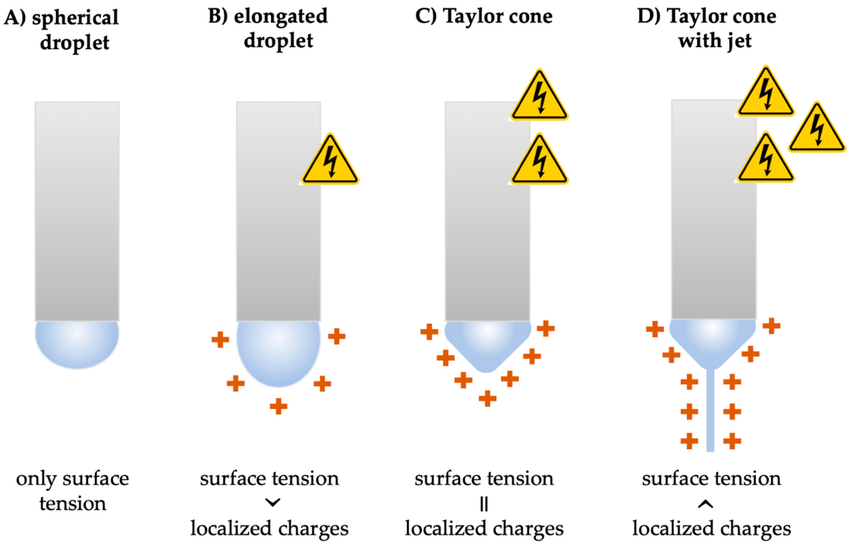

Electrospinning begins when a high voltage is applied to a polymer solution or melt at the needle tip. Charge accumulation at the droplet surface creates an electrostatic pulling force that competes with the liquid’s surface tension. When the electric force exceeds surface tension, the droplet elongates into a Taylor cone, from which a charged liquid jet is emitted.

During the initial stage, the jet travels linearly (the stable jet region). As the distance increases, charge repulsion destabilizes the jet, producing rapid bending and whipping motions. This instability dramatically increases the jet path length and elongational strain, resulting in the formation of ultrathin fibers. Solvent evaporation or melt solidification then “freezes” the polymer chains, producing solid nanofibers on the collector.

Figure 1: Typical electrospinning setup (syringe pump, needle, high-voltage supply, collector)

2.2 Solution Properties Governing Electrospinning Behavior

The formation of continuous nanofibers depends heavily on solution properties. Four parameters are particularly influential:

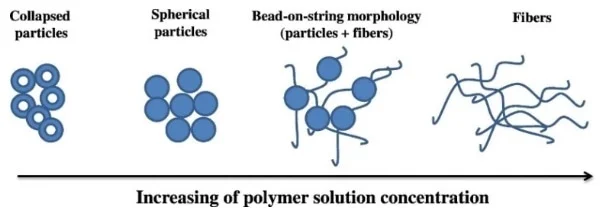

(1) Polymer Concentration & Chain Entanglement

A minimum level of chain entanglement is required to stabilize the jet.

Low concentration → electrospraying or beads-on-string morphology

Medium concentration → uniform fibers with controlled diameter

High concentration → excessively viscous and difficult to eject

(2) Viscosity and Viscoelasticity

Viscosity governs jet stability and resistance to capillary breakup.

Too low → bead formation

Optimal → smooth fibers

Too high → interrupted jet or needle clogging

(3) Conductivity

High conductivity enhances charge density, increasing stretching forces and typically reducing fiber diameter.

(4) Surface Tension

High surface tension resists jet formation and promotes bead defects. Surfactants or mixed solvents are often used to reduce surface tension and stabilize the jet.

Figure 2: Taylor cone formation under increasing electric field

Figure 3: Relationship between solution properties and fiber morphology (beads → uniform fibers)

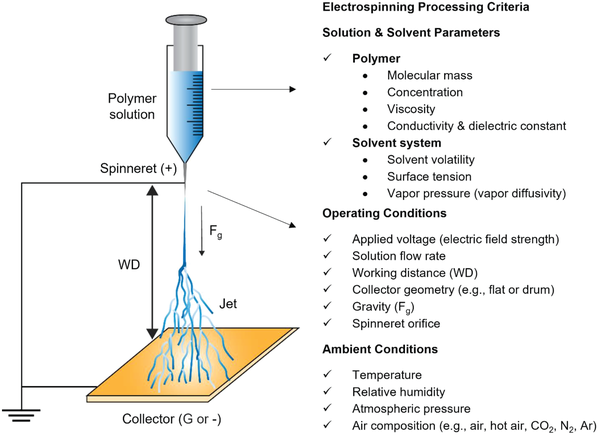

2.3 Processing Parameters in Electrospinning

Beyond solution chemistry, several operational parameters strongly influence fiber quality:

| Parameter | Effect on Jet / Fiber Morphology |

|---|---|

| Applied Voltage | Higher voltage increases electrostatic force; may reduce fiber diameter but too high causes instability. |

| Flow Rate | Low flow promotes full solvent evaporation; high flow leads to wet fibers, beading, or fiber merging. |

| Tip-to-Collector Distance (TCD) | Short distances cause incomplete drying; long distances cause whipping loss or poor deposition. |

| Environmental Conditions (Temperature, Humidity) | High humidity promotes surface porosity; temperature affects viscosity and solvent evaporation rate. |

Figure 4: Schematic representation of major electrospinning processing parameters

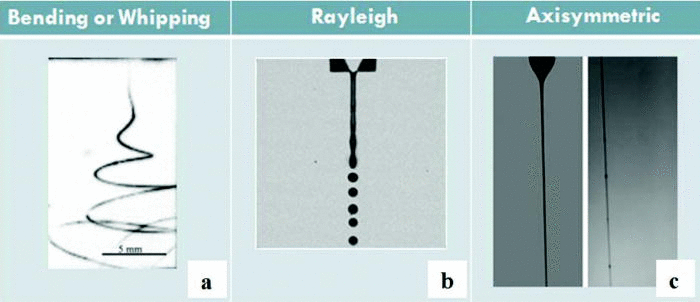

2.4 Jet Stability, Whipping Instability, and Solidification

Once the charged jet leaves the Taylor cone, it becomes susceptible to electrostatic repulsion and surrounding airflow. Small perturbations grow rapidly, leading to whipping instability, which is the primary mechanism enabling nanofiber formation.

Key behaviors in this stage include:

- Exponential growth of jet bending → dramatically increases stretching ratio

- Rapid decrease in jet diameter → transition from microscale to nanoscale

- Solvent evaporation occurring during flight → solidification before reaching the collector

Jets that lack sufficient viscoelasticity break apart and form droplets; thus, both solution elasticity and processing conditions together determine final morphology.

Figure 5: Jet instability modes during electrospinning (straight jet → bending → whipping)

2.5 Why Electrospinning Can Produce Nanofibers

Electrospinning enables nanofiber formation due to:

Non-mechanical elongation: Electrostatic forces, not rollers, drive stretching.

Extremely high extension ratios: Whipping path length can exceed 100× the straight-line distance.

Rapid solidification: Solvent evaporation during flight “freezes” nanoscale structures.

Versatility in material systems: Compatible with polymers, composites, blends, biomaterials, ceramics precursors, and conductive fillers.

This combination of high stretching force, fluid instability, and rapid solidification makes electrospinning uniquely capable of producing fibers far thinner than those produced via melt or solution spinning.

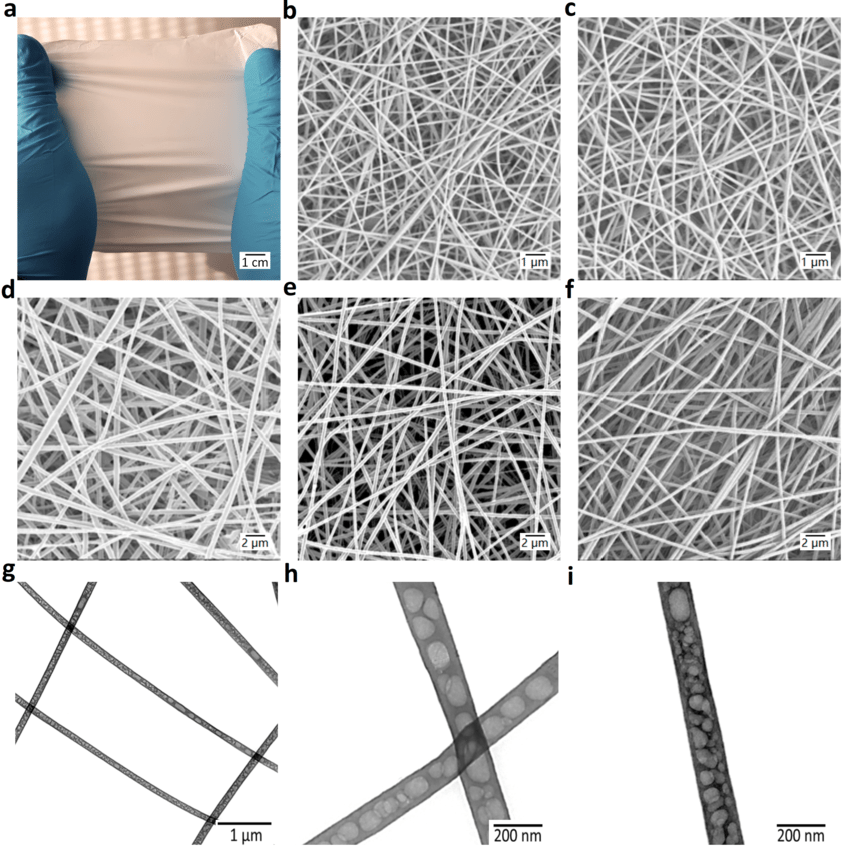

Figure 6: SEM images of electrospun nanofiber mats

2.6 Summary

Electrospinning is governed by the interplay of electrostatic forces, fluid dynamics, and polymer physics. Solution properties such as viscosity, concentration, conductivity, and surface tension determine whether fibers or beads form. Process parameters—including voltage, flow rate, tip-to-collector distance, and environmental humidity—further refine fiber diameter and morphology. The hallmark of electrospinning is the bending/whipping instability that dramatically stretches the jet to nanoscale diameters. Together, these fundamentals make electrospinning a uniquely powerful platform for fabricating polymer nanofibers with tunable structures and functionalities.

3. Discussion of a Peer-Reviewed Paper

3.1 Selected Paper

Quasi-Solid-State Polymer Electrolyte Based on Electrospun Polyacrylonitrile/Polysilsesquioxane Composite Nanofiber Membrane for High-Performance Lithium Batteries (Liu et al., Materials, 2022). Publicly available full text: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9658625/

3.2 Overview of the Paper

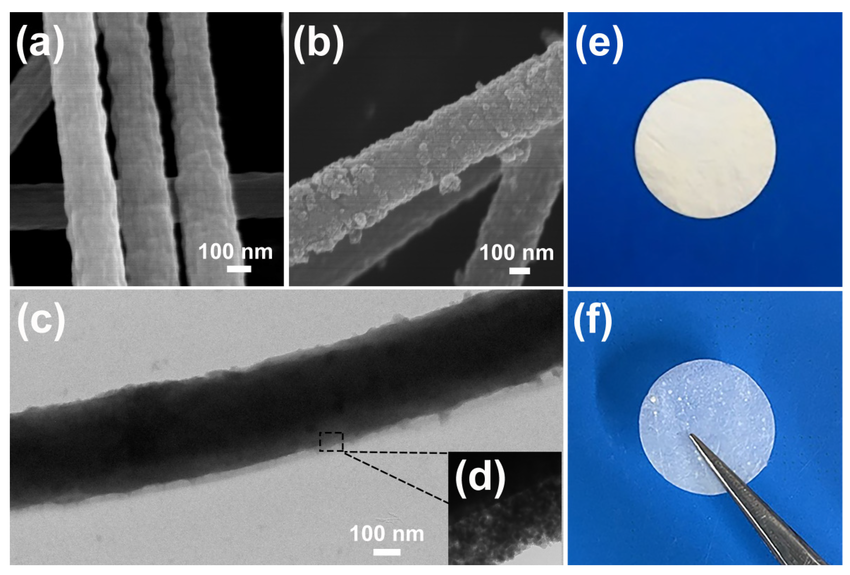

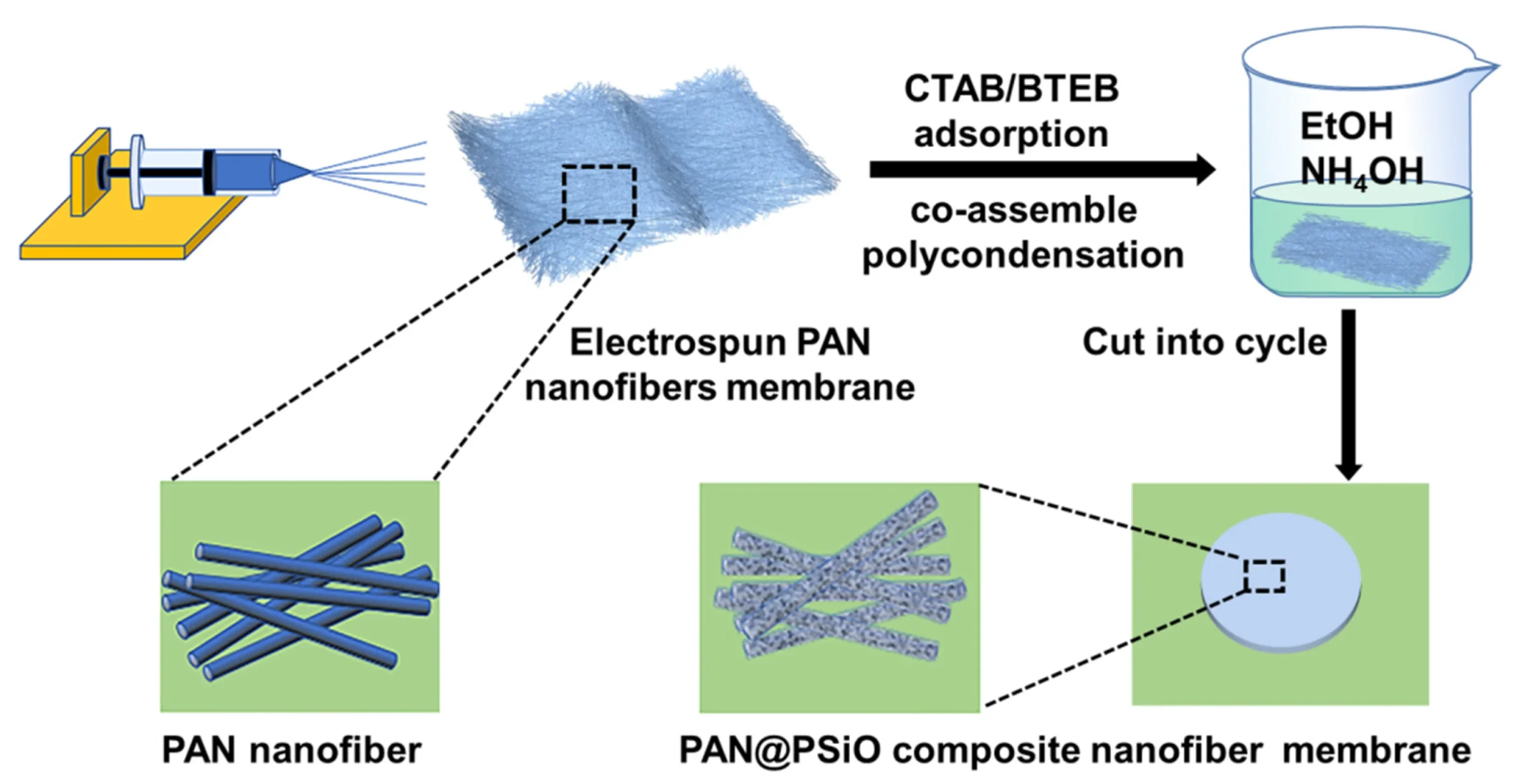

This study investigates an electrospun polyacrylonitrile (PAN) nanofiber membrane that is modified with a polysilsesquioxane (PSiO) coating via a sol–gel process, creating a composite nanofiber scaffold for quasi-solid-state lithium battery electrolytes. The authors first produce a highly porous, interconnected PAN nanofiber network using electrospinning, then uniformly deposit a thin PSiO layer on the fiber surfaces. The PSiO coating enhances mechanical stability, thermal resistance, electrolyte retention, and interfacial compatibility, enabling the composite membrane to function simultaneously as a separator and a polymer electrolyte scaffold. Electrochemical measurements demonstrate that the membrane achieves an ionic conductivity of 1.58 × 10⁻³ S·cm⁻¹ at room temperature, an electrochemical stability window up to 4.8 V, and stable cycling performance in Li/LiFePO₄ cells. The paper highlights how nanofiber architecture and nanoscale surface engineering improve ionic transport, electrolyte uptake, and mechanical robustness, making the composite suitable for high-performance lithium battery applications.

Figure 7 : SEM comparison of PAN nanofibers vs PAN@PSiO composite nanofibers

3.3 Connection Between This Paper and Chapter Concepts

This paper provides a direct and clear illustration of the processing–structure–property relationships emphasized throughout this chapter. From a processing standpoint, the authors use two advanced fabrication techniques—electrospinning and sol–gel surface coating—to introduce hierarchical multi-material features into a single membrane, reflecting the chapter’s discussion of “processing-derived microstructure control.” Structurally, the resulting composite membrane exhibits nanoscale porosity, interconnected channels, high surface-area-to-volume ratios, and a conformal inorganic–organic hybrid coating, all of which map directly onto the structural design principles described in Section 2. These structural features enable functional properties relevant to energy devices, including enhanced ionic conductivity, improved electrolyte uptake, higher mechanical strength, and a wider electrochemical stability window. Therefore, the paper strongly reinforces the chapter’s argument that electrospinning is a powerful platform for designing materials where nanoscale structure critically determines macroscopic performance, particularly for ion transport and device stability.

Figure 8: Process–structure–property schematic of composite nanofiber membranes

3.4 Why This Paper Is an Ideal Example for This Chapter

This paper is particularly suitable for inclusion in a chapter on electrospinning because it demonstrates the transition from fundamental nanofiber fabrication to functional device-level performance. Unlike studies focusing solely on morphological characterization, this work integrates processing, material design, and practical electrochemical evaluation. The composite PAN@PSiO membrane showcases how electrospinning can address real-world challenges in lithium batteries—such as poor mechanical stability, flammable liquid electrolytes, and inadequate ionic conductivity—by leveraging nanoscale porosity and hybrid material chemistry. The paper covers not only the materials science perspective but also the polymer engineering aspects, including electrolyte affinity, thermal stability, and separator functionality. For students, this paper exemplifies how electrospinning can evolve from a laboratory technique into a platform for advanced polymer-based energy devices.

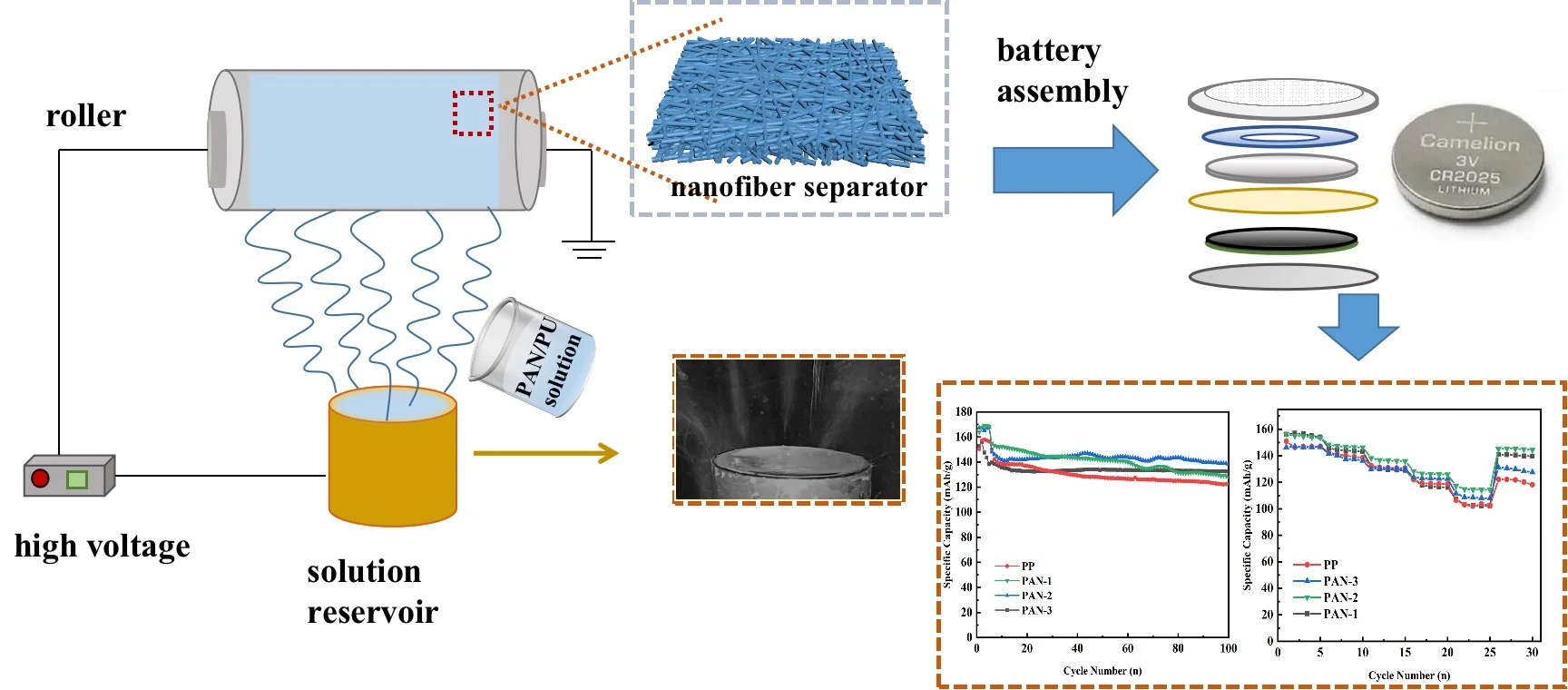

Figure 9: Battery application diagram for electrospun separators

3.5 Critical Evaluation and Limitations

Although the composite nanofiber membrane displays promising performance, several limitations remain. First, the ionic conductivity, while high for quasi-solid-state systems, is still significantly lower than that of liquid electrolytes, which may restrict rate performance in demanding applications. Second, although the PSiO coating improves mechanical strength, its long-term cycling durability, interfacial stability with metallic lithium, and resistance to large-volume changes are not fully demonstrated in the paper. Third, the study does not extensively address scalability; electrospinning and sol–gel coating can be challenging to adapt to industrial roll-to-roll manufacturing without optimizing throughput, fiber uniformity, and solvent recovery. Finally, the membrane’s compatibility with high-voltage cathodes and high-capacity anodes (beyond LiFePO₄) remains unclear and requires systematic evaluation. These gaps highlight opportunities for future research that builds upon the principles discussed in this chapter.

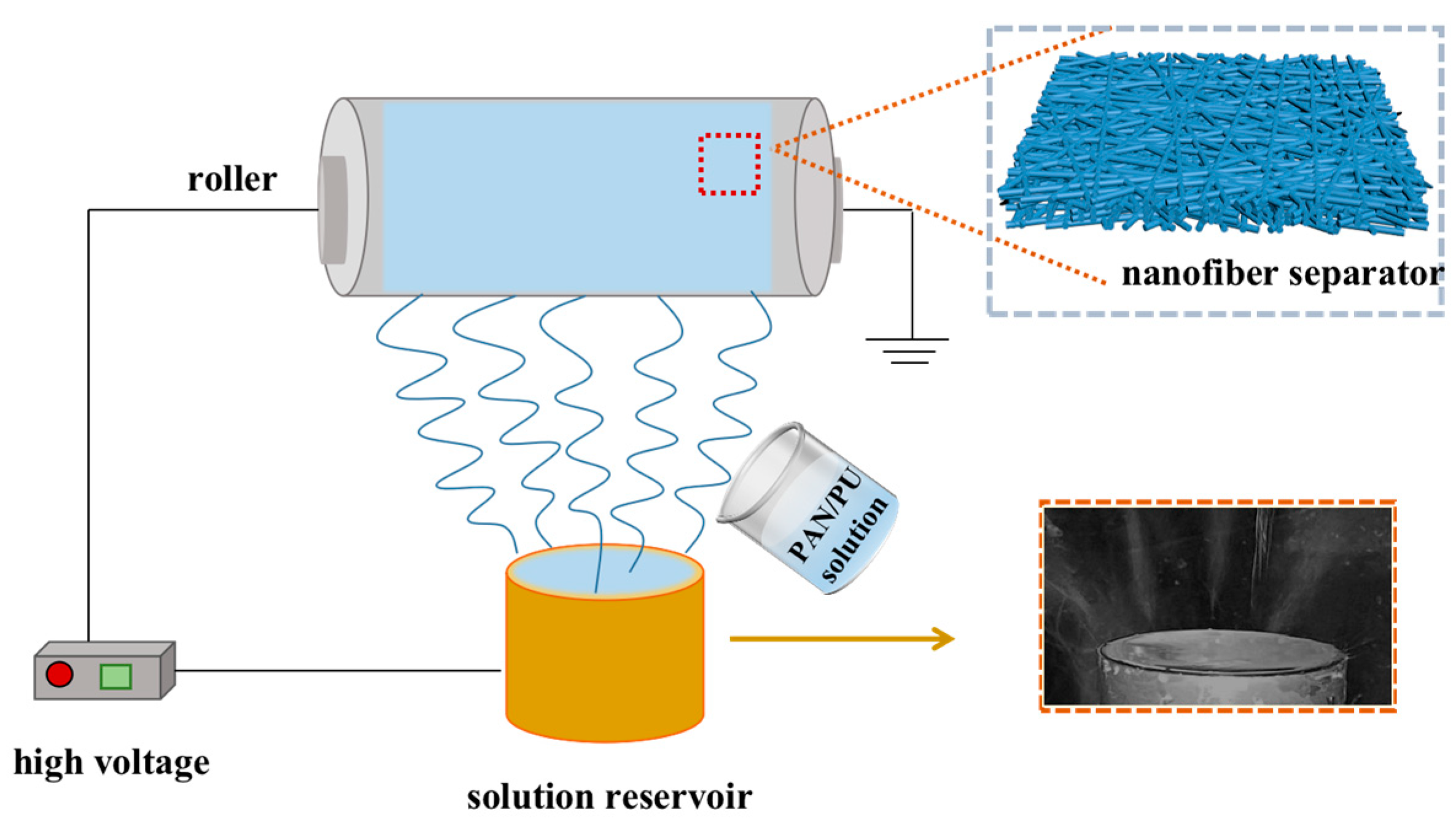

Figure 10: Electrospinning equipment and membrane preparation workflow

4. Interactive Elements

The following short quiz is designed to help reinforce key concepts from this chapter, including electrospinning fundamentals, polymer solution behavior, and structure–property relationships. These questions provide a quick self-check for readers to assess their understanding before moving on to the final sections of the chapter.

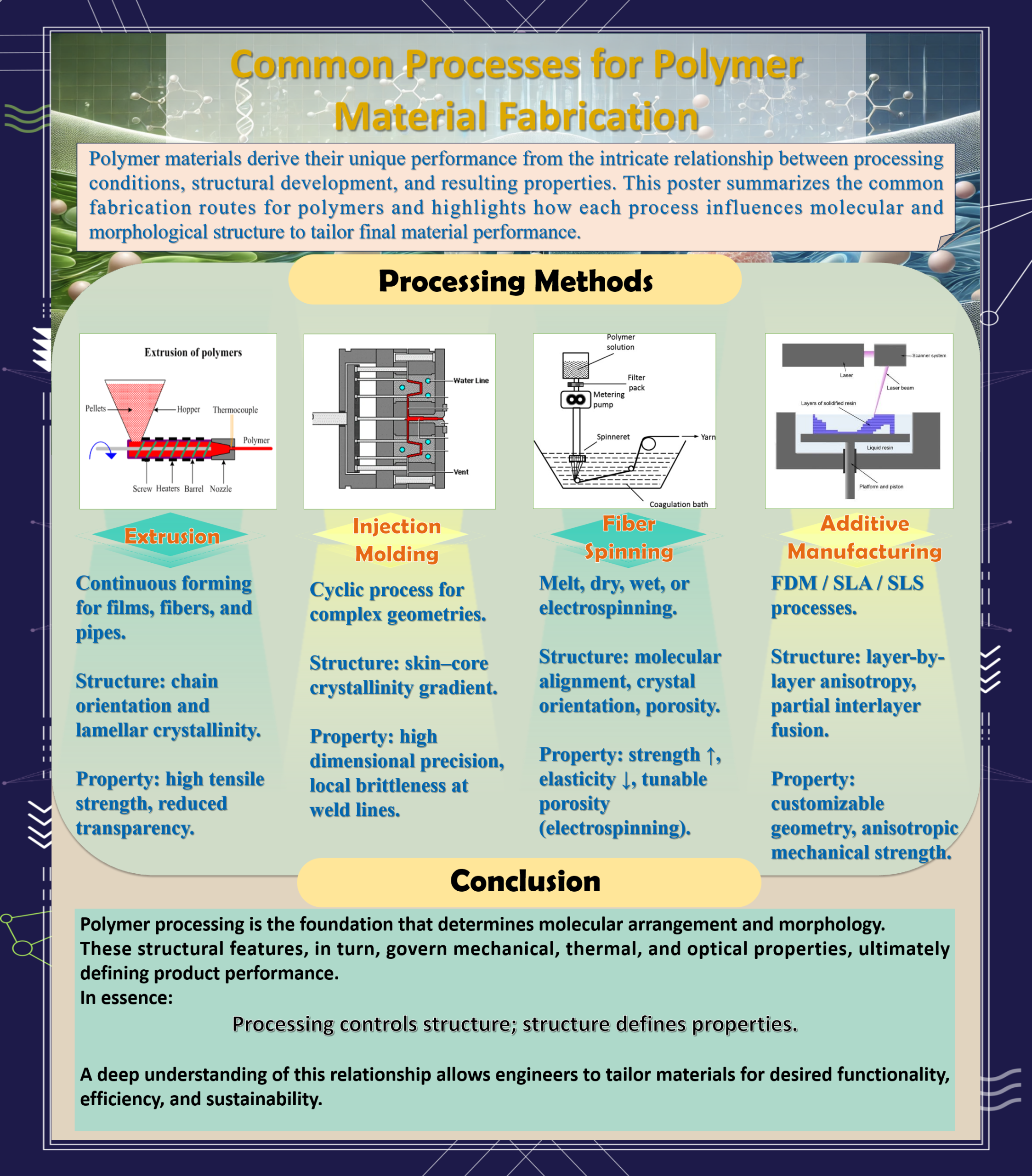

5. Graphical Abstract / Summary

6. References

- Li, D. & Xia, Y. Electrospinning of nanofibers: reinventing the wheel? Adv. Mater. 16, 1151–1170 (2004).

- Greiner, A. & Wendorff, J. H. Electrospinning: a fascinating method for the preparation of ultrathin fibers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 5670–5703 (2007).

- Ramakrishna, S. et al. Electrospun nanofibers: solving global issues. Mater. Today 9, 40–50 (2006).

- Persano, L., Camposeo, A., Tekmen, C. & Pisignano, D. Industrial upscaling of electrospinning and applications of polymer nanofibers: a review. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 298, 504–520 (2013).

- Huang, Z.-M. et al. A review on polymer nanofibers by electrospinning and their applications in nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 63, 2223–2253 (2003).

- Bhardwaj, N. & Kundu, S. C. Electrospinning: a fascinating fiber fabrication technique. Biotechnol. Adv. 28, 325–347 (2010).

- Reneker, D. H. & Yarin, A. L. Electrospinning jets and polymer nanofibers. Polymer 49, 2387–2425 (2008).

- Zhang, C., Yan, H., Liu, Y. & Xu, J. Recent advances in electrospun nanofibers for tissue engineering applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 9, 3049–3061 (2021).

- Zhu, M. et al. Electrospun nanofibers for energy applications. Chem. Rev. 117, 12702–12763 (2017).

- Xue, J., Wu, T., Dai, Y. & Xia, Y. Electrospinning and electrospun nanofibers: methods, materials, and applications. Chem. Rev. 119, 5298–5415 (2019).

- Li, X. et al. Nanofiber-based filters and triboelectric membranes for high-performance wearable sensors. Nano Energy 90, 106592 (2021).

- Lee, C. H., Shin, H. & Cho, I. S. Electrospun nanofibers for wearable electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2006900 (2021).

- Wang, Z. et al. High-performance nanofiber membranes for air filtration: electrospinning optimization and structure design. ACS Nano 14, 3273–3283 (2020).

- Ohkawa, K., Cha, D., Kim, H., Nishida, A. & Yamamoto, H. Electrospinning of chitosan. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 25, 1600–1605 (2004).

- Sill, T. J. & von Recum, H. A. Electrospinning: applications in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Biomaterials 29, 1989–2006 (2008).

- Agarwal, S., Wendorff, J. H. & Greiner, A. Use of electrospinning technique for biomedical applications. Polymer 49, 5603–5621 (2008).

- Matthews, J. A., Wnek, G. E., Simpson, D. G. & Bowlin, G. L. Electrospinning of collagen nanofibers. Biomacromolecules 3, 232–238 (2002).

- Pham, Q. P., Sharma, U. & Mikos, A. G. Electrospinning of polymeric nanofibers for tissue engineering applications: a review. Tissue Eng. 12, 1197–1211 (2006).

- Reneker, D. H. & Yarin, A. L. Electrospinning jets and polymer nanofibers. Polymer 49, 2387–2425 (2008).

- Deitzel, J. M., Kleinmeyer, J., Harris, D. & Beck Tan, N. C. The effect of processing variables on the morphology of electrospun nanofibers. Polymer 42, 261–272 (2001).

- He, J.-H., Wan, Y.-Q. & Xu, L. Nano‐microfiber electrospinning. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 460–461, 303–306 (2007).

- Kidoaki, S., Kwon, I. K. & Matsuda, T. Mesoscopic spatial designs of nano/microfibrous scaffolds created by electrospinning and their effects on in vitro cell responses. Biomaterials 27, 5681–5691 (2006).

- Li, W.-J., Laurencin, C. T., Caterson, E. J., Tuan, R. S. & Ko, F. K. Electrospun nanofibrous structure: a novel scaffold for tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 60, 613–621 (2002).

- Frenot, A. & Chronakis, I. S. Polymer nanofibers assembled by electrospinning. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 8, 64–75 (2003).

- Zussman, E., Burman, M., Yarin, A. L., Khalfin, R. & Cohen, Y. Tensile deformation of electrospun PAN nanofibers. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 44, 1482–1489 (2006).

- Zhang, C., Yuan, X., Wu, L., Han, Y. & Sheng, J. Study on the morphology of electrospun poly(vinyl alcohol) nanofibers. Eur. Polym. J. 41, 423–432 (2005).

- Zhang, Y. et al. Coaxial electrospinning of biodegradable polymer nanofibers for sustained drug delivery. Adv. Mater. 19, 721–725 (2007).

- Luo, C. J., Stride, E. & Edirisinghe, M. Mapping the influence of solubility and dielectric constant on electrospinning poly(vinyl alcohol) fibers. Macromolecules 45, 4669–4680 (2012).

- Townsend‐Nicholson, A. & Jayasinghe, S. N. Cell electrospinning: a unique biotechnique for encapsulating living organisms for 3D cell culture. Biomacromolecules 7, 3364–3369 (2006).

- Liu, Y., He, J.-H. & Yu, J.-Y. Bubble electrospinning for mass production of nanofibers. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 8, 393–396 (2007).

- Yarin, A. L. Fundamentals of spinning jets. Appl. Mech. Rev. 52, 311–362 (1999).

- Kenawy, E.-R. et al. Electrospun biodegradable nanofibers for the controlled release of tetracycline. J. Control. Release 81, 57–64 (2002).

- Casasola, R., Thomas, N. L. & Trybala, A. Electrospun poly(lactic acid) fibres for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Sci. 49, 7231–7246 (2014).