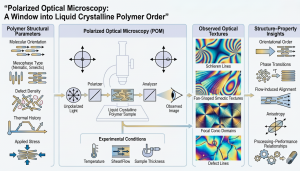

26 Polarized Optical Microscopy (POM) for the Characterization of Liquid Crystalline Polymers

Learning Objectives

-

Derive how birefringence and optical retardation generate contrast in crossed-polarizer microscopy, and predict intensity changes as a function of director orientation, thickness, and wavelength

-

Identify nematic and smectic mesophases in liquid-crystalline polymers using diagnostic polarized-light textures and classify topological defects from Schlieren brush patterns

-

Interpret focal conic, fan, and mosaic textures as geometric consequences of layered order and elastic constraints, and relate texture evolution to phase symmetry and boundary conditions

-

Quantify phase-transition sequences and mesophase stability windows using hot-stage POM and correlate optical signatures with thermodynamic transitions

1. Introduction

Liquid crystalline polymers (LCPs) are a distinct class of polymeric materials in which long-range orientational order emerges from molecular anisotropy while translational mobility is partially retained [1]. This coexistence places LCPs between crystalline solids and isotropic polymer melts, giving rise to mesophases (most commonly nematic and smectic) that are governed by symmetry breaking rather than lattice periodicity [2].

In contrast to conventional polymers, whose properties are dominated by crystallinity, entanglement density, and glass transition behavior, the macroscopic performance of LCPs is controlled by orientational order, defect topology, and elastic distortions of the director field [3]. Mechanical anisotropy, reduced melt viscosity, self-reinforcing alignment during processing, and unusual viscoelastic responses all originate from liquid crystalline ordering [4]. Consequently, characterization techniques that average over molecular or atomic length scales alone are insufficient to describe LCP behavior.

Polarized Optical Microscopy (POM) occupies a unique and foundational role in LCP characterization because it provides direct, real-space, symmetry-sensitive visualization of orientational order and its spatial variation [5]. Unlike scattering or spectroscopic methods that infer order indirectly, POM reveals mesophase symmetry, defect structures, and dynamic evolution under thermal or mechanical perturbation (Figure 2). For liquid crystalline polymers, POM is therefore not a preliminary or qualitative tool, but the primary experimental window into mesoscopic order and its physics [1,6].

2. Physical Origin of Optical Contrast in Liquid Crystalline Polymers

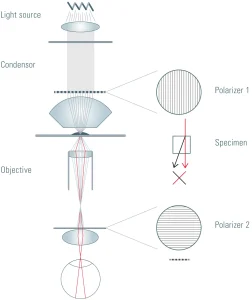

The contrast observed in POM arises from optical anisotropy (birefringence), which occurs when the refractive index of a material depends on the polarization direction of light [7]. In LCPs, birefringence originates from the anisotropic polarizability of mesogenic units and their collective alignment along a preferred direction known as the director [1].

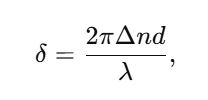

When linearly polarized light enters an anisotropic polymer domain, it splits into ordinary and extraordinary components that propagate with different refractive indices. The accumulated phase difference, or optical retardation, is given by:

where Δn is the birefringence, d is the sample thickness, and λ is the wavelength of light [7]. In a crossed-polarizer configuration, this phase retardation rotates the polarization state, allowing light transmission only in regions of nonzero orientational order [5].

Importantly, birefringence in liquid crystalline polymers is proportional to the scalar orientational order parameter, which measures the degree of alignment of mesogenic segments [2]. As a result, POM intensity variations reflect not only director orientation but also local variations in thermodynamic order, making the technique sensitive to gradients, distortions, and defects that are invisible to bulk-averaging methods such as DSC or GPC [6].

3. Continuum Description of Order: Director Fields and Elasticity

At mesoscopic length scales, liquid crystalline order is described using a continuum framework in which the local orientation is represented by a director field n(r) [1]. Spatial variations in this field incur elastic free-energy penalties associated with splay, twist, and bend deformations, quantified by the Frank elastic constants [8].

In liquid crystalline polymers, this continuum description must be augmented to account for polymer connectivity and chain stiffness, which modify elastic responses relative to low-molecular-weight liquid crystals [3]. Polymer backbones constrain director reorientation, leading to slower relaxation dynamics and enhanced metastability of distorted configurations [4].

POM provides a direct experimental manifestation of these elastic distortions. Variations in brightness and color correspond to spatial gradients in the director field, allowing elastic deformation modes to be inferred visually when interpreted within liquid crystal elasticity theory [6].

4. Topological Defects and Schlieren Textures in Nematic Polymers

A defining feature of nematic order is the inevitable presence of topological defects, which arise because the director field cannot remain continuous everywhere under symmetry and boundary constraints [8]. In nematic phases, these defects take the form of disclinations whose topological charge is quantized in half-integer units due to head–tail symmetry [9].

Under polarized light, nematic LCPs typically exhibit Schlieren textures, characterized by dark brushes radiating from defect cores. The number of brushes corresponds directly to the strength of the defect, providing immediate information about defect topology [10]. The density, mobility, and annihilation of these defects observed by POM reflect elastic constants, anchoring conditions, and relaxation mechanisms [6].

In polymeric nematics, defect dynamics differ fundamentally from those in small-molecule systems because chain connectivity restricts molecular reorientation [3]. POM thus serves as a powerful probe of polymer-specific constraint effects through observation of defect persistence and slow annihilation kinetics.

As illustrated in Figure 3, rapid cooling traps liquid crystalline polymers in highly defective, non-equilibrium states, whereas slow cooling promotes defect annihilation and the development of long-range orientational order detectable by POM.

5. Smectic Ordering, Layer Geometry, and Focal Conic Textures

Smectic liquid crystalline polymers exhibit one-dimensional positional order in addition to orientational order, resulting in layered structures with a well-defined spacing [1]. The geometric incompatibility between layered ordering and macroscopic boundaries gives rise to characteristic focal conic domains, which appear under POM as fan-shaped or elliptical textures [11].

These textures encode information about layer compression modulus, curvature elasticity, and defect energetics [8]. In polymeric smectics, chain folding, backbone rigidity, and side-chain architecture strongly influence layer stability, leading to textures that evolve over extended timescales [4]. POM is uniquely suited to capture these slow dynamics, which are often inaccessible to scattering techniques alone.

6. Thermal Phase Behavior and Hot-Stage Polarized Microscopy

Using POM with precise temperature control transforms it into a powerful method for mapping phase sequences and transition pathways in LCPs [12]. Transitions such as crystalline → smectic → nematic → isotropic are accompanied by abrupt changes in texture and birefringence that can be directly observed [2].

Compared with differential scanning calorimetry, POM is often more sensitive to weak or continuous transitions that involve small enthalpy changes [13]. Moreover, POM reveals spatial heterogeneity, phase coexistence, and nucleation fronts during transitions, providing insight into kinetic effects and metastability [4].

7. Flow-Induced Alignment and Rheo-Optical Polarized Microscopy

A hallmark of liquid crystalline polymers is their extreme sensitivity to flow during processing [14]. Under shear or extensional deformation, LCPs undergo rapid alignment of mesogenic units along the flow direction, leading to dramatic reductions in viscosity and highly anisotropic final properties [3].

Rheo-optical POM, which combines mechanical deformation with polarized light imaging, enables direct visualization of flow-induced ordering, defect suppression, and nonequilibrium alignment states [15]. Experiments have demonstrated shear-induced isotropic–nematic transitions and persistent flow-aligned textures in thermotropic LCP melts [14]. These observations underpin the industrial exploitation of LCPs in high-strength fibers and molded components.

8. Interpretation, Strengths, and Limitations of POM

The power of POM lies in its symmetry sensitivity, real-time capability, and direct visualization of mesoscopic order [5]. However, optical textures are not unique fingerprints; multiple director configurations can generate similar images [10]. Rigorous interpretation therefore requires grounding in liquid crystal elasticity, topology, and polymer physics [8].

For this reason, POM is most effective when used in conjunction with complementary techniques such as X-ray scattering or rheology, which constrain structural interpretation and provide quantitative length-scale information [13].

9. Conclusion

Polarized Optical Microscopy is the most fundamental and indispensable technique for characterizing liquid crystalline polymers. By directly visualizing orientational order, defect topology, and phase evolution, POM provides insight into the physical mechanisms that govern processing behavior and macroscopic performance. When interpreted rigorously within the framework of liquid crystal theory and polymer physics, POM is not a qualitative imaging tool but a theory-rich, mechanistic characterization method central to advanced polymer science.

References

-

de Gennes, P. G., & Prost, J. (1993). The physics of liquid crystals (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

-

Collings, P. J., & Hird, M. (1997). Introduction to liquid crystals: Chemistry and physics. Taylor & Francis.

-

Donald, A. M., Windle, A. H., & Hanna, S. (2006). Liquid crystalline polymers. Cambridge University Press.

-

Warner, M., & Terentjev, E. M. (2007). Liquid crystal elastomers. Oxford University Press.

-

Miller, D. S., Wang, X., & Abbott, N. L. (2013). An introduction to optical methods for characterizing liquid crystals. Langmuir, 29(10), 3159–3185.

https://doi.org/10.1021/la303649q -

Dierking, I. (2003). Textures of liquid crystals. Wiley-VCH.

-

Born, M., & Wolf, E. (1999). Principles of optics (7th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

-

Kleman, M., & Lavrentovich, O. D. (2003). Soft matter physics: An introduction. Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-21637-1 -

Oswald, P., & Pieranski, P. (2005). Nematic and cholesteric liquid crystals. Taylor & Francis.

-

Chandrasekhar, S. (1992). Liquid crystals (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

-

Gray, G. W., & Goodby, J. W. (1984). Smectic liquid crystals. Leonard Hill.

-

Driscoll, P. (1988). Phase transitions in thermotropic liquid crystalline polymers. Polymer, 29(7), 1155–1162.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0032-3861(88)90010-7 -

Wunderlich, B. (2005). Thermal analysis of polymeric materials. Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-23629-2 -

Mather, P. T., Romo-Uribe, A., & Han, C. D. (1997). Flow-induced ordering in thermotropic liquid crystalline polymers. Macromolecules, 30(26), 7977–7986.

https://doi.org/10.1021/ma970676y -

Laiho, A., Hietala, S., Paajanen, V., & Seppälä, J. (2007). Rheo-optical methods for polymer melts. Review of Scientific Instruments, 78(1), 015109.

https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2434742 - Li, L., Salamonczyk, M., Shadpour, S., Zhu, C., et al. (2018). An unusual type of polymorphism in a liquid crystal. Nature Communications, 9(1), Article 3160.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03160-9