37 Structure-Property Relationships in Design Principles and Applications of Polymeric Fluorescent Probes

Al Mojnun Shamim

1.Introduction:

Fascinating element Fluorescence, in which molecules take in light and then give it out at longer wavelengths, is now an important part of modern science and industry. Polymeric fluorescent probes represent the forefront of this field. They are complex macromolecular structures that combine the flexibility of polymers with the sensitivity of fluorescence detection. These probes have changed a lot of things, including biological imaging, environmental sensing, security measures, and optoelectronic devices [1].

Polymeric fluorescent probes are very interesting because they can turn molecular-level interactions into optical signals that can be seen. Polymeric probes outperform small molecule fluorophores in terms of sensitivity, photostability, and multifunctionality. The polymer backbone is more than just a passive support structure; it also plays an active role in how the probe works, affecting everything from how well it dissolves and how it aggregates to the type of fluorescence it emits [2].

A detailed grasp of the links between structure and property is at the basis of making good polymeric fluorescence probes. The probe’s fluorescence qualities, how sensitive it is to target analytes, and how well it works in different situations are all determined by the complex interactions between its chemical composition, molecular structure, and macroscopic features. Scientists may change the attributes of probes, like their emission wavelength, quantum yield, and how they react to environmental changes, by changing these structural elements [3].

By the end of this chapter, readers will gain not only a theoretical understanding of how molecular structure influences fluorescence properties in polymeric systems but also practical insights into designing and applying these probes. As we stand on the cusp of new discoveries and innovations in this dynamic field, the principles discussed here will serve as a foundation for future advancements, inspiring the next generation of scientists and engineers to push the boundaries of what’s possible with polymeric fluorescent probes.

Learning Objectives:

At the end of the chapter, readers will get an idea of the following:

1. Basic knowledge of polymeric fluorescent probes and why they are important in current science and technology.

2. Fundamental concepts of fluorescence and key polymer ideas relevant to the construction of fluorescent probes.

3. The important link between the chemical structure of polymers and their fluorescence characteristics.

4. How the structure of polymers affects how well fluorescence probes work.

Strategies for improving fluorescence performance and adjusting probe parameters for certain uses.

5. A summary of the most frequent ways to make polymeric fluorescent probes and the most important ways to test them.

Practical uses of polymeric fluorescent probes, especially for biological imaging, sensing, and keeping an eye on the surroundings.

2. Fundamentals

2.1. Basic Ideas About Fluorescence

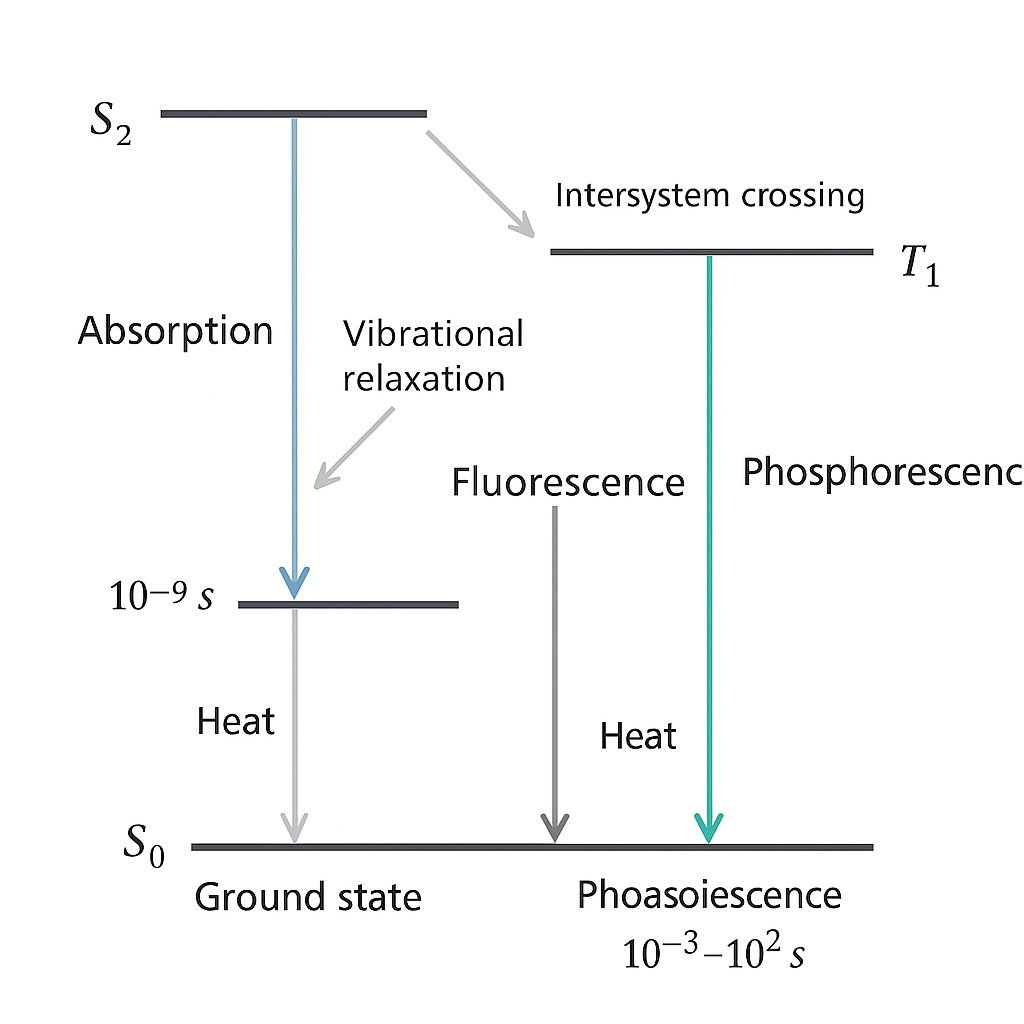

Fluorescence is a type of luminescence in which a substance takes in light at one wavelength and gives out light at a longer wavelength [4]. There are a few important ideas that go into this process:

Excitation: When an electron absorbs a photon, it moves from its ground state to an excited state.

Vibrational relaxation: The excited electron quickly loses energy through processes that don’t involve radiation, and it settles into the lowest vibrational level of the excited state.

Emission: The electron goes back to its ground state and gives off a photon with less energy (longer wavelength) than the photon that was absorbed.

The Stokes shift is the difference between the excitation and emission wavelengths, which is usually between 10 and 100 nm.

Quantum yield is the ratio of photons that are emitted to photons that are absorbed. It shows how well the fluorescence process works.

2.2 Main Concept of Polymers

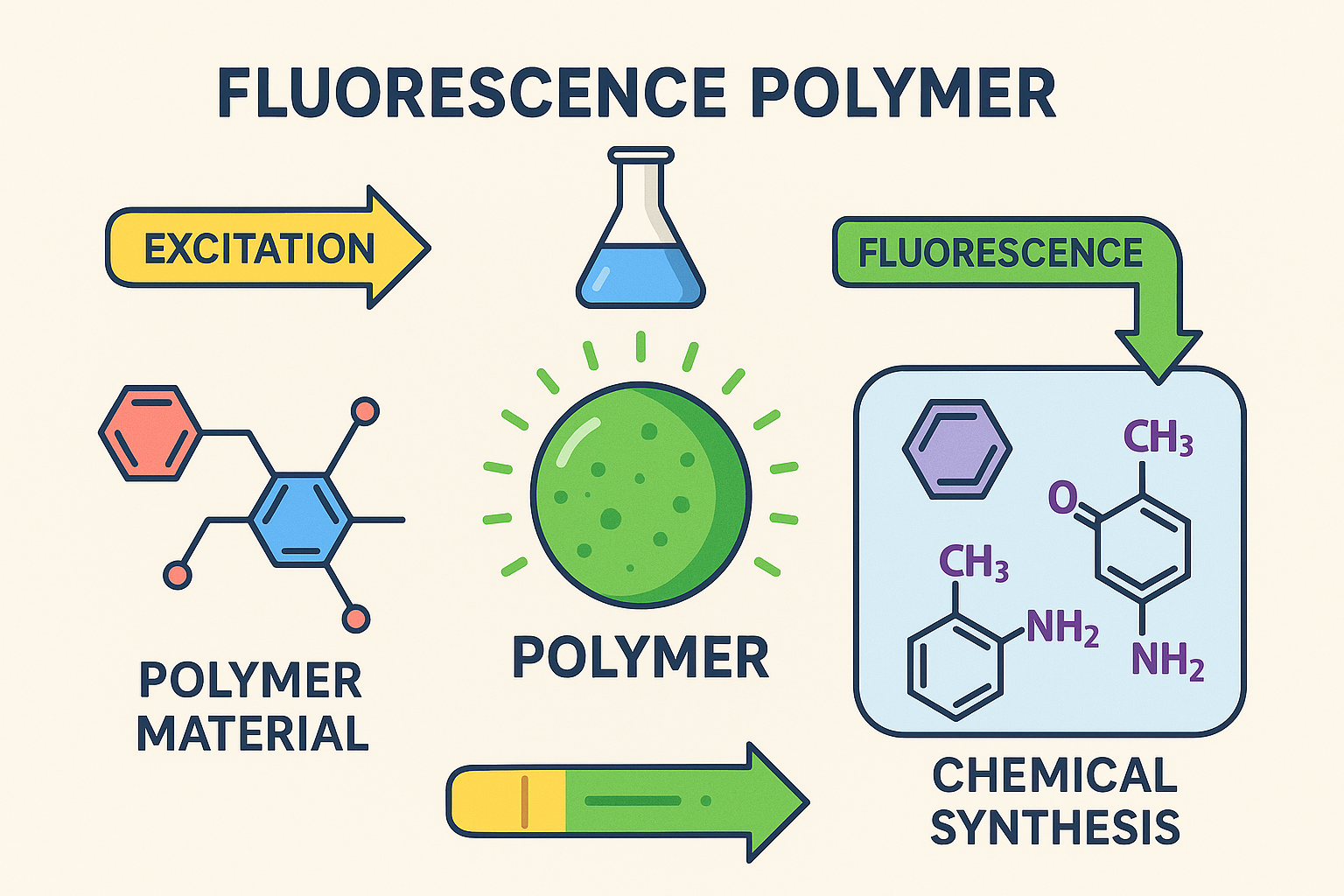

To properly understand how the structure and properties of polymeric fluorescence probes are related, you need to know some basic things about polymers (Figure 1):

Polymeric composition: The chemical makeup of the repeating units that make up the polymer chain. This can have a big effect on how the probe works.

Polymer structure: The way the monomers are arranged in the chain, such as in a linear, branching, or network structure, has an effect on the probe’s physical and optical properties.

The molecular weight: It is the sum of the molecular weights of all the repeating units. It affects things like how soluble, viscous, and dynamic the chain is.

The diversity of polymers: It has become the range of molecular weights in a polymer sample. These variations can change how uniform the probe’s properties are.

3. Relationships between structure and property

The chemical structure of polymeric fluorescent probes significantly influences their fluorescence properties.

Heteroatoms: Adding heteroatoms like N, O, or S can affect the electronic structure, which can change the fluorescence properties and make it possible for specific interactions with analytes.

Functional groups: Some functional groups can make a molecule respond to stimuli (like pH-sensitive groups) or provide it with places to be changed even further.

Rigidity: Rigid structures tend to have higher quantum yields since they have fewer avenues for energy to go without radiation.

Conjugated systems: When the polymer backbone or side chains have longer π-conjugation, the absorption and emission spectra usually shift to the red end of the spectrum, and the fluorescence intensity can also increase (Figure 2).

4. Synthesis

4.1. Common Synthesis Methods

Ring-Opening Polymerization (ROP): This method is useful for making luminous polymers that break down naturally, including those made from lactide or caprolactone monomers.

Condensation Polymerization: This process makes it possible to make conjugated polymers that naturally glow, like poly(p-phenylene vinylene) derivatives.

Post-polymerization modification: This one lets you connect fluorophores to polymers that have already been made. This gives you more freedom in how you construct your probes and lets you employ sensitive fluorophores that might not survive the polymerization conditions.

4.1 Characterization Techniques

Methods for Microscopy: Sending Electron Microscopy (TEM): Shows nanostructures in pictures. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) looks at the shape and mechanical properties of surfaces.

Fluorescence Spectroscopy: This method looks at emission spectra, quantum yields, and fluorescence lifetimes. Analyzes chiral structures and changes in shape using circular dichroism

X-ray Methods: X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Looks at the architecture of crystals. Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS) looks at structures on the nanoscale.

These methods give us a lot of information about the physical, chemical, and optical properties of polymeric fluorescent probes assist us in their creation and application.

5. Applications:

Cellular Imaging:

Polymeric probes can be made to target certain parts of cells, like membranes, organelles, or nucleic acids. This lets you see cellular activities in great detail. Because they can use more than one fluorophore, multiplexed imaging lets you see different targets at the same time.

Benefits in Biological Systems:

Polymeric probes typically demonstrate lower cytotoxicity relative to small-molecule dyes.

Their adjustable qualities make them more useful in complicated biological systems since they may be tailored to fit different biological conditions.

Chemical Process Control:

Polymeric fluorescence probes are used in factories to monitor chemical reactions and process parameters.

Because they are sensitive to changes in temperature, pH, or chemical makeup, they can be used to optimize processes very accurately.

Sensing the environment:

These probes can sense changes in the environment, including variations in pH or the presence of certain glasses. They are utilized in smart packaging technologies that show whether a product is still good or has gone stale.

6. Peer-reviewed paper

The paper “Aggregation-Induced Emission: Together We Shine, United We Soar” by Tang et al. (Accounts of Chemical Research, 2019) provides an authoritative summary of the principles, molecular design strategies, and applications of Aggregation-Induced Emission (AIE).

6.1 Brief Overview

The authors explain that AIE (Aggregation-Induced Emission) luminogens (AIEgens) exhibit minimal fluorescence in dilute solution but become highly emissive upon aggregation, a behavior fundamentally opposite to the traditional aggregation-caused quenching observed in many planar aromatics. The authors show that the Restriction of Intramolecular Motion (RIM) causes fluorescence amplification. The study emphasizes the substantial applications of AIE-active polymeric materials, including bioimaging, chemical and biological sensing, theranostics, optoelectronics, and environmental monitoring. The research collectively establishes AIE as a revolutionary concept in the development of next-generation luminous materials, particularly in the field of polymer science.

6.2 Connection with the Chapter

Connections between Changes in Structure to Performance:

One of the main ideas in this chapter is how structural engineering makes tunable fluorescence possible. The publication gives a lot of examples of how molecular twisting, polymer rigidity, conjugation length, and functional groups change the intensity and wavelength of emissions.

Improves the Practical Applications Part

The study offers direct case studies and examples demonstrating how AIE-active polymeric probes attain high sensitivity, improved signal amplification, and superior biocompatibility, which are described earlier in this chapter, like biological imaging, environmental sensing.

Paper Link: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00263

7. Conclusion:

The chapter thoroughly examines the complex relationships between polymer structure and fluorescence characteristics within sensing applications. It highlights the necessity of rational design in making polymeric fluorescent probes that work well, focusing on important elements including chemical composition, polymer architecture, and photophysical mechanisms. By looking at case studies like the AIE-active fluorescent porous polymers used to identify imidacloprid, it shows how structure-property correlations may be used in real life to build probes. In the conclusion, this chapter gives readers the basic knowledge and useful tips they need to create and improve polymeric fluorescent probes for a wide range of uses in analysis and environmental monitoring.

References:

[1] Geng, T.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, G.; Ma, L.; Ye, S.; Niu, Q. A Covalent Triazine-Based Framework from Tetraphenylthiophene and 2,4,6-Trichloro-1,3,5-Triazine Motifs for Sensing o-Nitrophenol and Effective 1-2 Uptake. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 777−784.

[2] Shen, R.; Liu, Y.; Yang, W. Y.; Hou, Y. Q.; Zhao, X. L.; Liu, H. Z. Triphenylamine-Functionalized Silsesquioxane-Based Hybrid Porous Polymers: Tunable Porosity and Luminescence for Multianalyte Detection. Chem. − Eur. J. 2017, 23, 13465−13472.

[3] Das, G.; Biswal, B. P.; Kandambeth, S.; Venkatesh, V.; Kaur, G.; Addicoat, M.; Heine, T.; Verma, S.; Banerjee, R. Chemical Sensing in Two Dimensional Porous Covalent Organic Nanosheets. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 3931−3939.

[4] Skorjanc, T.; Shetty, D.; Valant, M. Covalent Organic Polymers and Frameworks for Fluorescence-Based Sensors. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 1461−1481.

[5]B. Z. Tang, X. Mei, S. Chen, J. Wang, and J. W. Y. Lam, “Aggregation-Induced Emission: Together We Shine, United We Soar,” Accounts of Chemical Research, vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 88–97, 2019.