13 Glass Transition, Free Volume, and Plasticization

ysun63

1. Introduction

The glass transition temperature (Tg) is one of the most fundamental thermal parameters governing polymer behavior in both processing and end-use environments. Unlike melting, which corresponds to first-order phase transitions in crystalline domains, the glass transition is a kinetic phenomenon that reflects a dramatic change in segmental mobility as amorphous polymer chains transition from a rigid, glassy state to a flexible, rubbery state. As the temperature approaches Tg, cooperative long-range motions become activated, enabling energy dissipation, increased ductility, and viscoelastic relaxation. Below the glass transition temperature (Tg), mobility is highly restricted, resulting in stiff, brittle behavior characteristic of amorphous glasses.

A key theoretical framework for understanding Tg is free-volume theory, which describes how chain mobility depends on the microscopic unoccupied volume available for molecular rearrangement. Free volume increases with temperature, enabling faster relaxation and viscous flow above Tg. Factors such as polymer architecture, side-chain geometry, crosslink density, penetrant concentration, and environmental exposure all influence free volume and therefore shift Tg. Small molecules such as water, alcohols, and organic solvents often act as plasticizers, weakening intermolecular interactions and increasing free volume, thereby lowering the glass transition temperature (Tg) and reducing modulus.

In engineering applications—including packaging, coatings, adhesives, medical devices, 3D-printed materials, and membranes—plasticization can be either intentionally engineered or unintentionally introduced via solvent absorption or exposure to humidity. Understanding glass transition behavior, free-volume mechanisms, and plasticization effects is essential for designing polymer systems with adequate thermal resistance, dimensional stability, and mechanical performance.

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, students should be able to:

- Define the glass transition temperature and explain how segmental mobility varies across the glass transition.

- Describe free-volume theory and its role in controlling polymer relaxation and viscoelastic behavior.

- Apply the WLF equation to model temperature-dependent relaxation near Tg.

- Distinguish between external, internal, and environmental plasticization mechanisms.

- Analyze experimental data (DSC, DMA) to identify Tg shifts caused by penetrants or plasticizers.

- Explain how plasticization modifies modulus, toughness, and dimensional stability in engineering polymers.

2. Explanation of Key Concepts2.1 Glass Transition and Segmental Mobility

The glass transition represents a temperature range over which polymer segmental mobility changes by many orders of magnitude. Below the glass transition temperature (Tg), the polymer is in a glassy state in which cooperative motion is frozen and relaxation times may exceed years. Above Tg, chain segments can move collectively, reducing modulus by two to three orders of magnitude.

Fox and Flory demonstrated that Tg correlates with molecular weight because chain ends contribute extra free volume that facilitates motion [1]. As a result, low-molecular-weight polymers have significantly lower Tg due to their higher concentration of chain ends. In semi-crystalline polymers, Tg pertains only to amorphous regions, which serve as tie-chains between crystalline lamellae.

Temperature-dependent relaxation near Tg is often described using the Williams–Landel–Ferry (WLF) equation, which relates the shift factor aT to the temperature difference (T-Tg) [2]. This equation underpins time–temperature superposition (TTS) for constructing viscoelastic master curves.

2.2 Free-Volume Theory

Free-volume theory provides a molecular model for the changes in mobility that occur at Tg. The free volume is defined as the unoccupied volume within the polymer that permits segmental rearrangements. As temperature increases above Tg, the free-volume fraction grows approximately linearly, enabling cooperative rearranging regions (CRRs) to activate more quickly.

The total free volume can be expressed as:

- f(T) = f₀ + α(T − Tg)

where α is the thermal expansion coefficient of free volume.

Below the glass transition temperature (Tg), free volume decreases over time as the polymer undergoes physical aging, progressively stiffening as density increases and mobility decreases. Struik’s seminal work showed that physical aging leads to increases in modulus and decreases in creep compliance as the polymer structure relaxes toward equilibrium [3]. Aging is especially critical in amorphous thermoplastics used in optical lenses, medical components, and barrier films.

2.3 Plasticization Mechanisms

Plasticizers are small molecules that reduce the glass transition temperature (Tg) and soften the polymer by increasing free volume or decreasing intermolecular attractions. There are three principal modes:

-

External plasticization: Introduced intentionally, such as phthalates or citrate plasticizers in PVC and cellulose derivatives. These molecules insert between chains, reduce cohesive energy, and increase segmental mobility. Sears and Darby provided extensive data showing that classical plasticizers significantly lower Tg, often by 20–80 °C, depending on loading [4].

-

Internal plasticization: Achieved through copolymerization with flexible monomers, incorporation of long soft segments, or addition of flexible side chains. Internal plasticizers become part of the polymer backbone or side groups, offering permanent and homogeneous mobility enhancement.

-

Environmental plasticization (Solvent-Induced Plasticization, SIP): A critical category for engineering applications. Water, ethanol, acetone, and other small molecules diffuse into polymers, temporarily increasing free volume. This type of plasticization is responsible for humidity-dependent modulus changes in epoxies, solvent-softening in PMMA, and swelling in packaging materials. Kavda et al. demonstrated that exposure to alcohols and water induces significant softening and changes in molecular mobility in PMMA [5].

2.4 Thermal and Mechanical Consequences

Plasticization has several measurable effects:

- Decrease in Tg, observed by DSC as a shift in the heat-capacity step.

- Lower modulus, especially near Tg, due to increased mobility.

- Increased damping, shown by higher tan δ peaks in DMA.

- Greater ductility and impact resistance are sometimes beneficial for toughness.

- Dimensional instability, particularly when the penetrant distribution is nonuniform.

- Reduced long-term stiffness, potentially compromising structural integrity.

Chen et al. demonstrated that confinement and substrate interactions alter free-volume distribution and effective Tg in thin PMMA films, illustrating how morphology and interfaces modify transition behavior [6].

3. Discussion of a Peer-Reviewed Paper

To deepen the understanding of how glass transition, free volume, and plasticization operate in real polymer systems, this section examines the study by Kavda, Golfomitsou, and Richardson (2023) [5], which investigated the response of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) to prolonged exposure to various solvents. While PMMA is widely considered a rigid, transparent thermoplastic with a glass transition temperature (Tg) near 105 °C, its susceptibility to environmental plasticization makes it an ideal model system for elucidating how small-molecule penetrants modify free-volume structure, chain mobility, and mechanical integrity.

3.1 Summary of Experimental Approach

Kavda et al. conducted a systematic examination of PMMA specimens immersed for extended periods in four solvents: water, ethanol, isopropanol, and petroleum ether. These solvents vary dramatically in polarity and hydrogen-bonding capacity, enabling the authors to probe how solvent–polymer interactions influence the severity of plasticization. Their analysis employed multiple complementary characterization techniques, including:

- Unilateral NMR measurements are used to quantify solvent uptake profiles and monitor mobility changes within the polymer matrix.

- ATR-FTIR spectroscopy detected alterations in PMMA’s carbonyl and ester functional groups, revealing changes in the local chemical environment.

- Mass change tracking is used to determine solvent absorption levels and swelling behavior.

- Optical examination of surface features, including microcracks, whitening, and surface roughness.

This multimodal approach enabled the authors not only to quantify solvent penetration kinetics but also to characterize the resulting changes in microstructure and mobility—two core phenomena that are directly linked to Tg and plasticization theory.

3.2 Solvent Uptake and Penetration Behavior

One of the most striking findings of the study is the profound difference between polar and nonpolar solvents in their ability to penetrate PMMA. Polar solvents such as ethanol and water permeated deeply and rapidly, whereas petroleum ether exhibited negligible uptake. These results are consistent with expectations from free-volume theory and Flory–Huggins-type interaction parameters.

Polar solvents possess a strong affinity for the carbonyl groups in PMMA. Their ability to form hydrogen bonds enables them to insert between polymer chains, increasing local free volume. As solvent molecules accumulate, they create “plasticized domains” in which molecular mobility is substantially higher. These domains grow with time and may eventually overlap, leading to macroscopic softening.

Kavda et al. observed that the solvent concentration profiles were nonuniform, with higher penetrant concentration near the surface. This finding is consistent with classical diffusion-controlled plasticization, in which the local Tg decreases as solvent concentration increases. The presence of Tg gradients through the thickness has considerable implications for dimensional stability, warpage, and crack initiation during drying.

3.3 Chemical and Microstructural Changes

ATR-FTIR spectra revealed noticeable changes in the intensity and shape of PMMA absorption bands after prolonged solvent exposure. In particular:

- Shifts in the C=O stretching region indicated perturbation of the ester environment due to hydrogen bonding or dipole interactions.

- Changes in the CH₂ and CH₃ stretching regions suggested subtle increases in backbone mobility.

- Appearance of new bands in alcohol-exposed samples reflected residual solvent retained within the matrix.

These spectroscopic signatures underscore how penetrants disrupt PMMA’s intermolecular interactions. According to free-volume theory, weakening of intermolecular constraints lowers the activation energy required for segmental motion, thereby depressing Tg and increasing α-relaxation rates. Thus, the chemical evidence from the study strongly supports the theoretical framework described earlier in this chapter.

Optical examinations revealed whitening, microcracks, and surface roughness in heavily plasticized samples. Such features emerge when solvent-induced swelling generates internal stresses that exceed local yield strength. These phenomena reflect the interplay among swelling gradients, Tg depression, and viscoelastic softening, highlighting the mechanical consequences of plasticization.

3.4 Evidence of Plasticization and Tg Depression

Although the study did not directly measure Tg using DSC or DMA, the combination of their swelling, NMR, and FTIR results clearly points to strong plasticization effects. Increases in molecular mobility inferred from NMR relaxation times correspond to an effective Tg depression, consistent with the qualitative predictions of the Fox–Flory equation [1] and WLF scaling [2].

The authors observed:

- Higher solvent uptake → increased mobility → stronger plasticization

- Polar solvent exposure → most dramatic free-volume expansion

- Residual solvent after drying → persistent Tg reduction

These findings mirror the behaviors predicted by classical plasticizer models described by Sears and Darby [4], where additive molecules increase free volume and reduce cohesive energy density. In the case of PMMA, even low concentrations of ethanol or water act analogously to traditional plasticizers.

The paper’s observations are consistent with the notion that environmental plasticization can be as significant as formulated plasticization. This demonstrates that polymer design must account for real-world exposure conditions, particularly for PMMA optical components, adhesives, and protective coatings.

3.5 Connection to Free-Volume Theory and Physical Aging

The study provides valuable insights into the dynamic relationship between free volume and physical aging. Freshly exposed PMMA exhibits rapid solvent uptake and increased mobility, but upon drying, only partial recovery occurs. This suggests physical aging is interrupted or altered by solvent exposure, leaving behind microvoids or reorganized free-volume distributions.

These observations echo Struik’s description of aging disruptions in amorphous polymers [3], in which plasticization temporarily increases molecular mobility, erases the aging history, and then allows the polymer to re-age along a new path once penetrants leave. Thus, solvent exposure not only modifies Tg but also permanently alters relaxation behavior.

3.6 Implications for Engineering Applications

Kavda et al.’s work highlights numerous implications for practical polymer use:

- Optical devices (e.g., PMMA lenses)

Solvent-induced whitening or microcracking can compromise transparency and durability. - Adhesives and coatings

Exposure to solvents during cleaning or service can reduce Tg and stiffness, leading to premature failure. - 3D-printed PMMA components

Residual solvent from post-processing can act as an unintended plasticizer, altering mechanical properties. - Cultural heritage and conservation

PMMA-based objects exposed to humid or polluted environments may degrade through plasticization.

Overall, this study provides a compelling real-world demonstration of how environmental plasticization alters glass transition behavior, molecular mobility, and mechanical integrity. Its results reinforce the importance of understanding free-volume mechanisms, solvent interactions, and the glass transition temperature (Tg) in polymer design and application.

4. Interactive Elements

4.1 Quiz

Test the understanding of polymer–solvent compatibility using Hansen Solubility Parameters with this quick interactive question.

4.2 YouTube VideoResources

Designgekz. (n.d.). Glass transition temperature (Tg) in plastics or polymers | Jagadish Atole | Designgekz [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tlebmw8JrLI

Explains molecular origins of Tg and factors affecting mobility, reinforcing concepts in this chapter.

4.3 Chapter Slides

Glass_Transition_Free_Volume_Plasticization

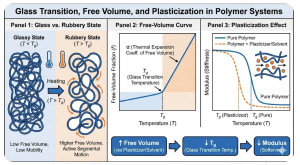

This slide provides a visual summary of how polymer mobility, free volume, and plasticization mechanisms change across the glass transition, supporting the key concepts discussed in this chapter.

5. Graphical Abstract

6. References

[1] Fox, T. G., & Flory, P. J. (1950). Second-order transition temperatures and related properties of polystyrene. I. Influence of molecular weight. Journal of Applied Physics, 21(6), 581–591. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1699711

[2] Williams, M. L., Landel, R. F., & Ferry, J. D. (1955). The temperature dependence of relaxation mechanisms in amorphous polymers and other glass-forming liquids. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 77(14), 3701–3707. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01619a008

[3] Struik, L. C. E. (1978). Physical aging in amorphous polymers and other materials. Elsevier.

[4] Sears, J. K., & Darby, J. R. (1982). The technology of plasticizers. Wiley.

[5] Kavda, S., Golfomitsou, S., & Richardson, E. (2023). Effects of selected solvents on PMMA after prolonged exposure: Unilateral NMR and ATR-FTIR investigations. Heritage Science, 11, 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-00881-z

[6] Chen, J., Li, J., Xu, L., Hong, W., Yang, Y., & Chen, X. (2019). The glass-transition temperature of supported PMMA thin films with hydrogen bond/plasmonic interface. Polymers, 11(4), 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11040601