38 How do chemical structures affect polymers’ properties: from polarity, flexibility and secondary bonds

xguo29

Learning objectives

- Identify the three primary structural drivers of polymer properties: chain polarity, backbone flexibility, and secondary bonding.

- Relate these structural drivers to changes in thermal transitions (Tm and Tg)

- Deduce the physical characteristics of a material (stiff vs. flexible, hydrophobic vs. hydrophilic) based on its chemical formula.

- Formulate explanations for the performance of everyday polymer products using molecular-level reasoning.

Introduction

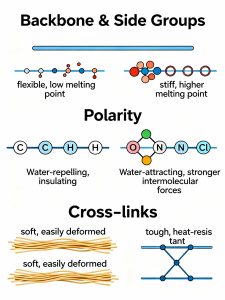

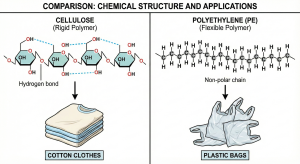

Polymers constitute a cornerstone of modern material science, pervading nearly every aspect of daily life and industrial application. Distinct from traditional metals and inorganic non-metals, polymeric materials offer unique physicochemical advantages, including versatility in synthesis and processing. This class of materials spans from naturally occurring biopolymers—such as the carbohydrates and proteins found in cotton and wool—to synthetic macromolecules derived from petroleum byproducts, such as polyethylene and polypropylene. Unlike the energy-intensive processing required for metals, polymers can often be synthesized and shaped under relatively mild conditions. However, the physical variance within this material class is immense: cellulose forms rigid, high-strength fibers, whereas polyethylene manifests as flexible, ductile films. This dichotomy raises a fundamental question: what governs these divergent material behaviors? The answer lies in the intrinsic chemical structure. The macroscopic properties of a polymer are strictly dictated by molecular-level factors, specifically backbone flexibility, polarity, and the presence of secondary intermolecular forces.

Polarity

The Impact of Side-Group Polarity on Polymer Properties

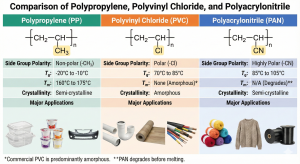

While backbone structure is fundamental to polymer classification, the specific chemical nature of pendant side groups acts as the primary determinant of macroscopic properties. A comparative analysis of polypropylene (PP), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polyacrylonitrile (PAN) illustrates this principle effectively. Despite all three sharing the linear C-C backbone, their applications diverge significantly due to differences in polarity and intermolecular forces.

- Polypropylene (PP): Non-Polar and Semi-Crystalline

PP features a non-polar methyl group attached to the backbone. With interactions governed solely by weak Van der Waals (London dispersion) forces, the polymer chains remain flexible and pack efficiently, resulting in a semi-crystalline structure. While its melting temperature (Tm) and glass transition temperature (Tg) are relatively low compared to polar polymers, PP retains sufficient thermal stability for use in microwaveable food containers. It is widely utilized in packaging and disposable items.

- Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC): Moderate Polarity and Amorphous

In PVC, a chlorine atom replaces the methyl group. Since chlorine (electronegativity 3.0) is significantly more electronegative than carbon (2.5), it creates a permanent dipole, introducing dipole-dipole interactions between chains. These interactions restrict chain mobility, raising the Tg and mechanical strength. Commercial PVC is typically amorphous; therefore, it exhibits a softening point rather than a sharp Tm. Due to its inherent rigidity and toxicity concerns, PVC is predominantly used in non-food structural applications like piping, often requiring plasticizers to optimize flexibility.

- Polyacrylonitrile (PAN): High Polarity and Fiber Formation

PAN possesses highly polar nitrile groups. The resulting strong dipole-dipole interactions create a rigid molecular network with a high Tg. Notably, PAN degrades before reaching a theoretical melting point due to its thermal instability (cyclization of nitrile groups will occur). However, these strong intermolecular forces allow PAN to form high-quality fibers that mimic the texture of wool (“acrylic”). Consequently, PAN is essential in the textile industry and serves as the primary precursor for high-strength carbon fibers due to its ability to form stable aromatic structures upon controlled heating.

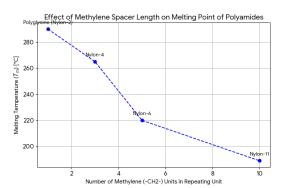

Flexibility

While functional groups primarily dictate chemical reactivity, the flexibility of the polymer backbone plays a critical role in determining thermal and mechanical behavior. This structure-property relationship is clearly exemplified in polyamides (nylons), a class of polymers defined by amide linkages separated by methylene spacers. A comparison of Polyglycine (Nylon-2), Nylon-6, and Nylon-11 illustrates how increasing the number of methylene units—and thus the distance between hydrogen-bonding amide groups—alters material performance.

Major applications of nylon

- Polyglycine (Nylon-2): As the simplest polyamide with the shortest repeating unit, polyglycine possesses a high density of intermolecular hydrogen bonds. This rigid structure results in an extremely high theoretical Tm that often exceeds its degradation temperature, rendering melt-processing nearly impossible. Furthermore, its high hydrophilicity and exposure of amide bonds lead to poor chemical resistance, limiting its practical utility.

- Nylon-6: With five methylene units separating the amide groups, Nylon-6 strikes an optimal balance between chain flexibility and intermolecular hydrogen bonding. Its melting point (~220oC) is high enough for structural applications but low enough for efficient melt-processing. This balance makes it a versatile material for textiles, ropes, and engineering plastics.

- Nylon-11: Containing ten methylene units per repeating unit, Nylon-11 is significantly more flexible than its counterparts. As noted in a recent study by Jariyavidyanont et al., increasing the methylene spacer length in polyamides linearly decreases Tm and Tg due to reduced hydrogen bond density and increased chain mobility. Consequently, Nylon-11 exhibits superior flexibility, impact resistance, and lower moisture absorption, making it ideal for tubing and flexible electronics where Nylon-6 might be too brittle or hygroscopic.

Secondary bonds

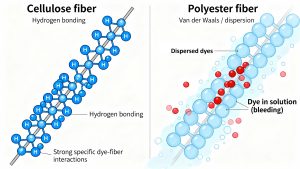

Why Chemistry Matters in Laundry: Hydrogen Bonding vs. Weak Interactions The common household problem of “color bleeding”—where dark dyes transfer to lighter clothes during washing—is a macroscopic demonstration of molecular-level bonding. While the phenomenon appears unpredictable, it is strictly dictated by the polymer composition of the fabric. For instance, cotton fibers are co

mposed of cellulose, a polymer featuring a high density of hydroxyl groups. When exposed to dyes containing polar groups like sulfonates or diazo arenes, these hydroxyl groups form strong hydrogen bonds. This specific type of secondary bonding creates a robust attraction that resists the solvating power of water. Conversely, polyester fibers lack these hydrogen-bonding sites. Without the ability to form strong secondary bonds, the interaction between the polyester backbone and polar dye molecules is limited to weaker physical forces. As a result, the dye is less securely anchored and is more prone to leaching out into the wash water and staining adjacent fabrics.

References

Du, M., Jariyavidyanont, K., Schick, C., & Androsch, R. (2025). Physical Aging and Young’s Modulus of Polyamide 11 Containing Different Crystal Polymorphs. Macromolecular Materials and Engineering, e00242.

Quiz

Interactive video