41 Influence and Regulation of Polymer Multilevel Architecture on Mechanical Properties

sliu72

Learning Objectives

By learning this chapter, the readers will have the ability to:

- Describe the hierarchical structural architecture of polymers, spanning from chemical to texture structures.

- Explain the specific mechanisms by which chemical structure, condensed-state structure, and texture structure influence mechanical properties.

- Understand the fundamental strategies for regulating polymer hierarchical structures through molecular design, processing techniques, and post-processing.

- Apply the principle of synergistic multi-level structural effects to explain the macroscopic mechanical behavior of specific polymers.

Introduction

The diverse mechanical behaviors of polymeric materials, ranging from everyday plastics to high-performance fibers, originate from their complex yet ordered hierarchical structures. The properties of polymers are not determined directly by their chemical composition alone but are transmitted and expressed through a series of structural levels spanning from the microscopic to the macroscopic scale. This layered architecture is termed the hierarchical structure of polymers. Understanding the intrinsic relationship between structure and properties forms the core scientific foundation for designing and synthesizing novel high-performance polymers, optimizing processing techniques for existing materials, and expanding the application domains of polymers.

The primary level of polymer structure is its chemical structure, referring to the chemical constitution of the individual macromolecular chains themselves. This includes the type of monomer, linkage patterns, stereochemical configuration, as well as molecular weight and its distribution. The chemical structure is the origin of all material properties, as it dictates chain flexibility, polarity, and the nature and magnitude of intermolecular interactions. For instance, polyethylene chains consisting solely of carbon-carbon single bonds in the backbone are highly flexible, whereas chains containing aromatic rings in the backbone, such as poly(p-phenylene terephthalamide) known as Kevlar fiber, exhibit rigid, rod-like characteristics.

When numerous such polymer chains assemble, they form higher-order structures. Through secondary bonding forces, the chain structures spontaneously arrange and pack into condensed-state structures with certain degrees of order. The two most prevalent condensed-state structures are the crystalline and amorphous states. Within crystalline regions, molecular chains are densely and regularly packed, providing the material with strength and modulus. In contrast, chain segments are disordered in amorphous regions, imparting flexibility and impact resistance to the material. Semi-crystalline polymers contain both regions, where crystallinity, lamellar thickness, and crystal polymorphs decisively influence mechanical performance. On a larger scale, the spatial organization of crystalline and amorphous domains, and the formation of morphologies like spherulites and lamellae, constitute the texture or suprastructure. Furthermore, molecular chain orientation induced by external force fields during processing represents another critical aspect of texture, which can dramatically enhance material strength and modulus along the orientation direction.

Therefore, the mechanical properties of polymers represent the integrated response of their hierarchical structures under external load. From flexible elastomers to rigid engineering plastics, from brittle polystyrene to high-impact ABS resin, this vast diversity in performance stems from the precise, full-chain regulation of hierarchical structures, from chemical design to physical assembly. This chapter will systematically dissect these structural levels, reveal the intrinsic mechanisms by which they influence mechanical properties, and explore scientific pathways for tailoring performance through the control of structure via synthesis and processing means.

Key Concepts

Chemical Structure (Chain Structure): The Molecular Basis of Properties

The chemical structure, or chain structure, of a polymer serves as the foundational building block for all its higher-order architectures. This level concerns the chemical construction of individual macromolecular chains. The chemical nature of the monomer determines the types of chemical bonds in the backbone. A backbone composed entirely of carbon-carbon single bonds, as in polyethylene, has a low barrier to internal rotation, resulting in highly flexible chains that allow the material to be easily deformed at room temperature, exhibiting toughness. Conversely, incorporating rigid units like aromatic rings into the backbone, as in poly(ethylene terephthalate) or polyimides, significantly increases chain rigidity, typically leading to materials with higher modulus and heat resistance, though potentially increased brittleness. The size and polarity of side groups are equally crucial. Bulky side groups, such as the phenyl ring in polystyrene, increase steric hindrance, restrict chain segment motion, and raise the glass transition temperature and modulus, but may induce brittleness. Polar side groups or strong hydrogen-bonding interactions, like the amide linkages in polyamides, can markedly enhance intermolecular forces between chains, thereby improving material strength, modulus, and thermal resistance. Molecular weight and its distribution are another determining factor. Mechanical properties are generally poor at low molecular weights. As molecular weight increases, the number of chain entanglements rises, enhancing the material’s strength, toughness, and melt viscosity. Once the molecular weight exceeds a critical entanglement molecular weight, further improvements in mechanical properties plateau. Therefore, through copolymerization, altering stereoregularity, or precisely controlling molecular weight, the potential range of a polymer’s properties can be pre-defined at the molecular level.

Condensed-State Structure: The Interplay of Order and Disorder

Countless polymer chains aggregate through secondary bonding interactions to form structures with long-range or short-range order, known as condensed-state structures. These primarily include the crystalline, amorphous, and liquid crystalline states. The crystalline state is characterized by the three-dimensional, long-range ordered arrangement of molecular chains. Polymers with regular chain structures and strong intermolecular forces tend to crystallize. Crystalline regions act like “physical cross-links” or reinforcing points within the material, effectively bearing external loads. Consequently, polymers with high crystallinity usually possess greater strength, modulus, hardness, and solvent resistance. However, excessively high crystallinity can also lead to embrittlement. Lamellar thickness within crystals significantly affects properties; thicker lamellae confer higher melting points and better mechanical performance. The amorphous state consists of randomly packed chains with greater freedom for segmental motion. The glass transition temperature is the most important characteristic parameter for amorphous polymers. Below this temperature, segmental motion is frozen, and the material is in a hard, brittle glassy state; above it, segments begin to move, and the material enters a rubbery or viscous flow state. Amorphous regions impart flexibility and impact toughness to polymers. Most common and engineering plastics are semi-crystalline polymers, containing both crystalline and amorphous regions. The ratio, size distribution, and interconnection of these two phases collectively determine the balance between the material’s modulus and toughness.

Texture Structure and Orientation: Micro-Morphology and Macroscopic Anisotropy

On a scale larger than the condensed-state structure, crystalline and amorphous domains further assemble into specific morphologies, known as texture or supramolecular structures. For example, during crystallization from solution or melt, polymers often form spherulites, which are polycrystalline aggregates growing radially from a central point. The size and perfection of spherulites influence material transparency and mechanical properties; typically, a structure of small, dense spherulites is more favorable for achieving balanced performance. Processing operations, especially those involving stretching or flow such as fiber spinning, extrusion, and film blowing, cause molecular chains to orient along the direction of the applied force. This orientation structure is an extremely important type of texture. Prior to orientation, chains exist as random coils, and strength is provided by relatively weak intermolecular forces. After orientation, chains extend and align along the stress direction, allowing the strong covalent bonds in the backbone to directly bear the load. This results in an order-of-magnitude increase in strength and modulus along the orientation direction. The high strength of fibers originates precisely from this highly oriented structure. Conversely, properties may be weaker in directions perpendicular to the orientation. This phenomenon, where performance varies with direction due to orientation, is called anisotropy. Understanding and controlling texture structure and orientation is key to manufacturing high-performance films, fibers, and plastic articles.

Polymer Structure and Assembly

Synergy of Hierarchical Structures and Strategies for Performance Control

The final mechanical properties of a polymer are the manifestation of the synergistic effects of all its structural hierarchies. For instance, the high impact resistance of a polymer may stem from the molecular design of a dispersed rubber phase, which forms a specific texture within an amorphous matrix and effectively initiates and terminates cracks upon impact. Therefore, the essence of performance control lies in the precise manipulation of these hierarchical structures. At the molecular design stage, flexible or rigid segments can be introduced via copolymerization or grafting to modulate chain flexibility and intermolecular interactions. During the processing stage, parameters such as cooling rate, application of tensile or shear fields, and use of nucleating agents can be controlled to regulate crystallinity, crystal form, spherulite size, and the degree of molecular chain orientation. Post-processing techniques like thermal annealing can perfect crystal structure and relieve internal stress, while stretching can further induce orientation. For example, ultra-drawing of polyethylene can produce ultra-high modulus fibers; rapidly quenching poly(ethylene terephthalate) yields films with low crystallinity suitable for packaging, whereas slow crystallization produces high-crystallinity material for engineering applications. This philosophy of stepwise construction and control from the molecule to the macro-scale is central to polymer materials science.

Peer-reviewed Paper Discussion

https://doi.org/10.1002/masy.19991470106

Research Overview

The selected peer-reviewed paper is the 1999 review article by Eric Baer, Anne Hiltner, and David Jarus, titled Relationship of Hierarchical Structure to Mechanical Properties. The core argument of the paper is that the mechanical properties of complex material systems originate from their hierarchically organized structure spanning from the nanoscale to the macroscopic level. The authors begin by systematically analyzing the intrinsic relationship between the outstanding performance of natural biological materials and their hierarchical structures. For instance, the six-level ordered structure of tendons provides excellent uniaxial tensile strength and toughness. Wood exhibits pronounced anisotropy due to the layered, orderly arrangement of cellulose from molecular chains to annual rings. Nacre achieves fracture toughness far exceeding that of its ceramic component through an alternating brick-and-mortar structure composed of inorganic platelets and an organic matrix. The article emphasizes that understanding the properties of these materials hinges on grasping three key elements: the scale of the structures, the interactions between different hierarchical levels, and the overall spatial architecture.

Subsequently, the paper successfully applies this analytical framework to synthetic polymer systems, demonstrating the feasibility of actively constructing hierarchical structures through processing and composite technologies. Several classic case studies are presented: the solid-state drawing of polypropylene induces spherulite deformation, lamellar rotation, and molecular chain orientation, enabling cooperative reorganization across multiple scales that substantially enhances both strength and toughness. Microlayer coextrusion technology is used to fabricate composites of polycarbonate and styrene-acrylonitrile copolymer, where precise control over the layer thickness of the brittle and ductile phases induces cooperative crazing and shear banding, transforming the material from brittle to tough overall. In impact-modified polycarbonate, the interparticle distance scale determines whether cavitation occurs randomly or in a coordinated array, significantly influencing the impact strength of the material. Collectively, these cases demonstrate that rationally constructing hierarchical structures in synthetic polymers by emulating natural design principles is an effective pathway for performance tailoring.

Connection to the chapter

This paper aligns closely with the theme of this chapter, providing solid theoretical support and rich illustrative examples. This chapter aims to explain how the hierarchical structural system of polymers, from chemical structure to condensed states, determines and influences their mechanical properties. The article by Baer et al. represents an in-depth elaboration and extension of this very principle.

Specifically, the paper strongly supports several learning objectives set forth in this chapter. In terms of expounding the hierarchical structural system, the detailed case studies of both biological and synthetic materials enable students to intuitively grasp the concrete manifestations of structural hierarchies extending from the molecular to the macroscopic scale. Regarding explaining how different structural levels affect properties, the article’s analysis of the mechanism by which different hierarchical levels in tendons fail successively under tension to absorb energy, along with its explanation of how layer thickness controls the failure mode in microlayer composites, vividly reveals the causal relationship between microscopic structural mechanisms and macroscopic mechanical responses. Most importantly, in understanding performance modulation strategies, the processes detailed in the paper, such as biaxial orientation and microlayer coextrusion, are prime examples of modifying the texture structure and, consequently, the macroscopic properties through processing methods, as emphasized in this chapter.

This review serves not only as authoritative substantiation of the core concepts in this chapter but also as an intellectual bridge connecting fundamental theory to advanced material design. It assists us in moving beyond an understanding of single, homogeneous polymers and helps establish a systematic conceptual framework for customizing material properties through multi-scale structural design.

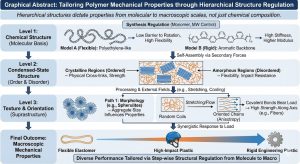

Graphical Abstract

References

- Meijer, H. E., & Govaert, L. E. (2005). Mechanical performance of polymer systems: The relation between structure and properties. Progress in polymer science, 30(8-9), 915-938.

- Meijer, H. E., & Govaert, L. E. (2003). Multi‐Scale Analysis of Mechanical Properties of Amorphous Polymer Systems. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics, 204(2), 274-288.

- Bermejo, R., Daniel, R., Schuecker, C., Paris, O., Danzer, R., & Mitterer, C. (2017). Hierarchical architectures to enhance structural and functional properties of brittle materials. Advanced engineering materials, 19(4), 1600683.

Interactive Quiz