30 Polymer Melt Spinning for Spunbond and Meltblown Nonwoven Processes: Principles and Fiber Formation Mechanisms

Nampil Cho

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the student will be able to:

-

Understand polymer melt spinning as the basis of spunbond and meltblown nonwoven processes

-

Distinguish key fiber formation mechanisms for each process

-

Interpret the role of processing parameters in controlling polymer rheology and fiber dimensions

-

Connect fiber morphology with resulting nonwoven performance properties

-

Recognize application-driven material requirements in nonwoven product design

Introduction

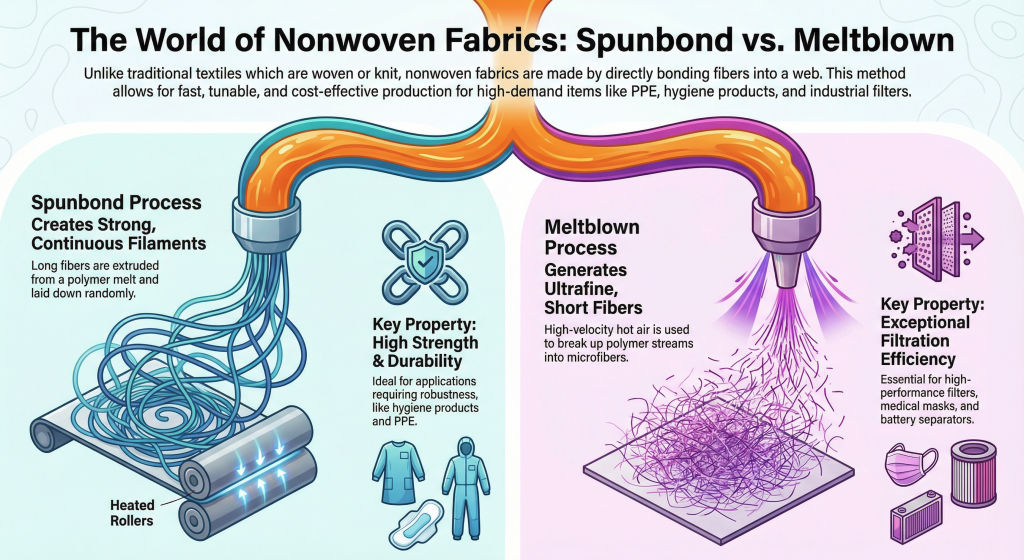

Nonwovens have become one of the most essential material platforms in modern industries, ranging from PPE(personal protective equipment) to hygiene products, filter media, and battery membrane. Unlike woven or knitted textiles that depend on the interlacing of continuous yarns, nonwovens are formed by directly and randomly bonding fibers together into a web. This manufacturing approach enables extremely high production rates, tunable structural design, and cost-effective processing.

Among the various nonwoven manufacturing technologies, spunbond and meltblown processes are the most widely used as they are both based on polymer melt spinning, a versatile technique to form thermoplastic fibers. In both processes, polymer pellets are melted, extruded through a spinneret, and then drawn into fine filaments followed by web formation. But, the mechanisms governing fiber formation differ significantly between the two techniques, resulting in different fiber sizes, web structures, and functional properties. Spunbond processes produce continuous filaments with relatively high mechanical strength, while meltblown processes generate ultrafine fibers that provide exceptional filtration performance.

This chapter introduces the fundamental principles of polymer melt spinning and explains how they translate into the operating mechanisms of spunbond and meltblown nonwoven manufacturing. By examining the relationships between processing parameters, polymer rheology, fiber morphology, and resulting performance, students can better understand how engineering decisions directly influence material functionality in nonwoven product design.

Polymer Melt spinning Fundamentals

Before introducing to specific nonwoven technologies, it is important to understand the underlying physics of polymer melt spinning. This process transforms solid polymer chips into fluid melt and finally into solid fibers through a series of thermal and mechanical operations.

The Extrusion and Spinning Mechanism

The process begins in the extruder, where polymer pellets or chips are subjected to heat and shear forces. A rotating screw melts and conveys the polymer, ensuring a homogeneous melt temperature and viscosity. The molten polymer is then forced by a metering pump through a spinneret(A metal die containing hundreds to thousands of microscopic holes).

Rheology and Fiber Formation

As the polymer exits the spinneret capillaries, it undergoes a phenomenon known as die swell (Barus effect), where the stream diameter briefly expands due to the relaxation of viscoelastic stresses built up in the capillaries. Immediately after, the extruder enters the quenching zone. Here, cool air solidifies the polymer streams while an external force with high-velocity air or mechanical rollers applies tension. This tension leads to draw-down, significantly reducing the fiber diameter compared to the spinneret hole size and aligning the polymer chains along the fiber axis to enhance mechanical properties.

Spunbond Process

Spunbond processing converts the melt spun filaments into a mechanically robust nonwoven web. After exiting the spinneret, the continuous filaments are guided downward by air flow and randomly laid onto a moving conveyor. This random laydown produces an entangled network of long fibers that ensures coverage and dimensional stability.

The key defining feature of spunbond is the continuity of the filaments. Because the fibers are not broken during attenuation, their length contributes strongly to tensile strength, tear resistance, and durability. To turn the loose fiber web into a functional fabric, the structure must be stabilized through bonding. The most common method is thermal (calender) bonding, where heated rollers partially melt the contact points between fibers to fuse them together. The resulting pattern of bonded points determines stiffness, flexibility, and drape.

Meltblown Process

The meltblown process uses the same melt-spinning origin as spunbond, but the fiber formation mechanism is different. Instead of maintaining continuous filaments, meltblown depends on high-velocity hot air to draw and attenuate the polymer melt immediately as it exits the spinneret.

As the molten polymer streams are extruded through micro sized orifices, a pair of hot air jets rapidly stretches and breaks up the streams into extremely fine fibers, often in the range of 1–5 μm or even sub micron. Because the fibers solidify during this intense attenuation, they lose continuity and deposit as short, highly entangled microfibers on the collector.

Unlike spunbond, no separate bonding step is required. The fibers are still tacky upon deposition, allowing self-bonding at contact points. This makes a dense, porous web structure with extremely high surface area (A critical factor for filtration applications).

Figure 1. Infographics on a Comparative Overview of Spunbond and Meltblown Processes Based on Polymer Melt Spinning Principles.

Processing – Structure – Property Relationships in Nonwoven

Nonwoven performance is directly governed by the structural cherateristic generated during fiber and web formation. Because spunbond and meltblown processes create fibers in different size and length ranges and bonding conditions, their final material properties diverge significantly.

Fiber Diameter and Orientation

Spunbond nonwovens are typically 15–40 μm in diameter and retain high molecular orientation due to controlled drawing. This results in strong, durable fabrics suitable for load-bearing applications such as hygiene back sheets and agricultural covers. In contrast, meltblown nonwovens are several times finer (1–5 μm or even <1 μm), producing much higher surface area and smaller pore sizes.

Bonding and Web Architecture

Thermal-bonded spunbond nonwovens exhibit discrete bonding points, where the surrounding fiber segments remain free to move. The resulting web offers high tensile strength yet maintains flexibility and drape. Meltblown webs, on the other hand, bond through fiber self-adhesion, generating a uniformly connected but more weak network. The lack of long fiber continuity reduces mechanical strength but enhances porosity.

Application-Driven Structure Tailoring

Manufacturers often combine spunbond and meltblown layers to balance properties (e.g., SMS: Spunbond–Meltblown–Spunbond). In PPE masks, the meltblown middle layer captures aerosols while the spunbond outer layers provide reinforcing strength and abrasion resistance.

Connection to Peer-Reviewed Research: Nanoval Technology as a Hybrid Melt-Spinning Approach

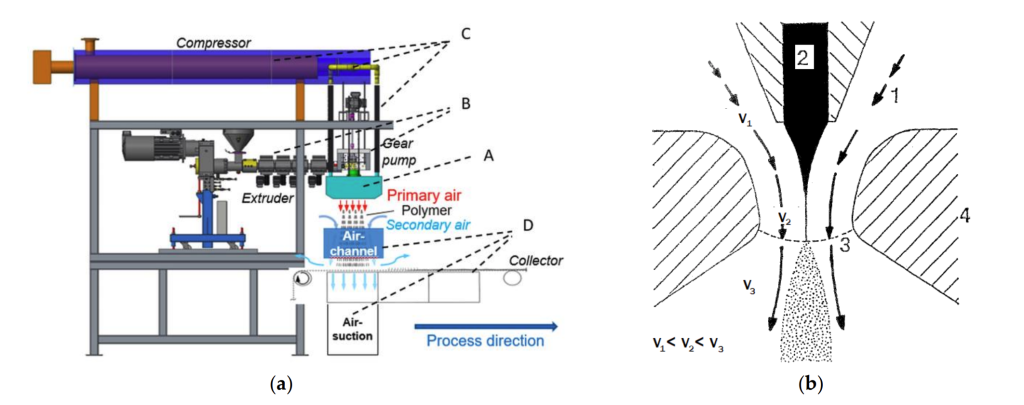

Figure 2. Nanoval process: (a) equipment layout and (b) airflow mechanism.

A recent study on Nanoval Technology (Figure. 2) introduces a manufacturing method that bridges the gap between conventional spunbond and meltblown processes. Like meltblown, Nanoval uses high-velocity air to attenuate the polymer melt. However, it utilizes a unique Laval nozzle design. This mechanism accelerates the air to supersonic speeds, causing the polymer filaments to split into finer strands. This allows the creation of fibers that are finer than spunbond (8–15 μm) but stronger and more continuous than typical meltblown microfibers.

The paper highlights three key advantages:

Improved Fiber Continuity: Unlike meltblown fibers that often break into short microfibers due to turbulence, Nanoval fibers generated via the Laval nozzle effect retain partial filament continuity, significantly enhancing mechanical strength.

Tunable Fiber Diameter: By adjusting the air-drawing geometry and attenuation pressure inside the nozzle, fiber sizes can be precisely tuned from fine (~10 μm) to sub-micron scales, enabling flexible structure design.

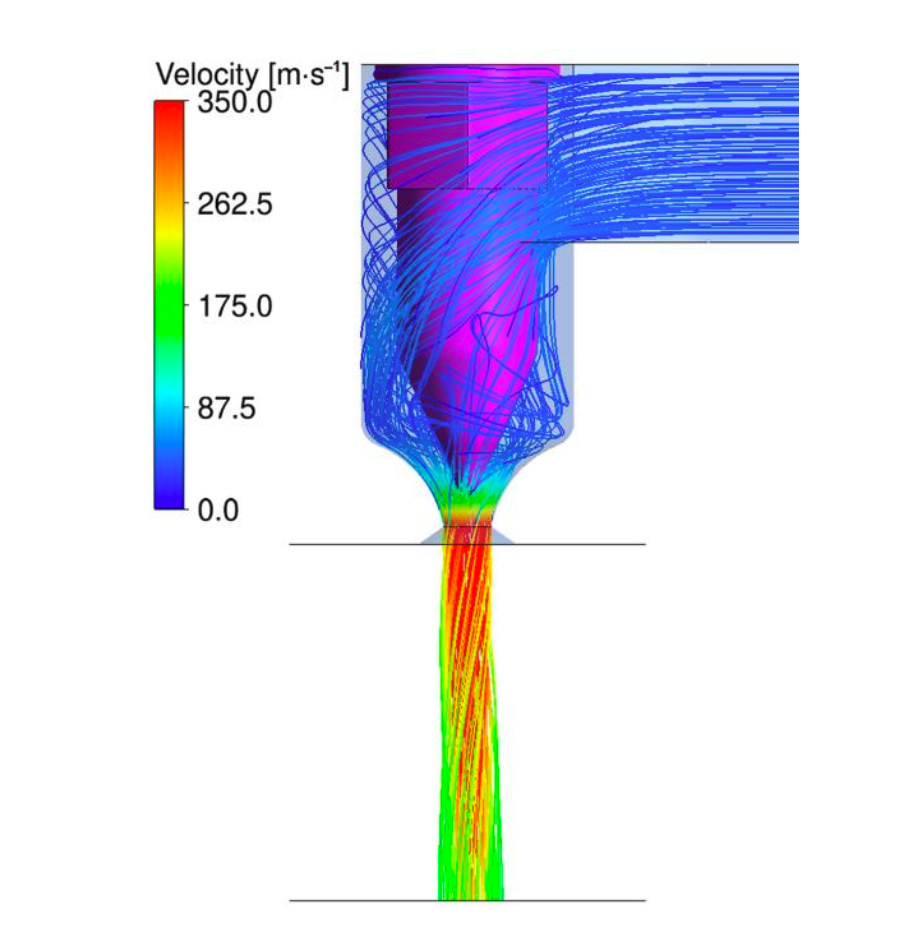

Figure 3. Simulation of air flow: streamlines for the center nozzlles.

Enhanced Web Strength vs. Filtration Trade-off: The resulting nonwoven web offers a balanced performance—higher tensile strength than meltblown and better filtration efficiency than spunbond.

Relevance to Chapter Concepts

These findings directly support the structure–property principles. Optimizing the melt spinning and attenuation conditions allows engineers to design nonwovens.

Spunbond vs Meltblown:

Test Your Understanding

Reference

- Wente, V. A. (1956). Superfine thermoplastic fibers. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry, 48(8), 1342–1346. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie50560a034

- Lasenko, I., Sanchaniya, J. V., Kanukuntla, S. P., Viluma-Gudmona, A., Vasilevska, S., & Vejanand, S. R. (2024). Assessment of Physical and Mechanical Parameters of Spun-Bond Nonwoven Fabric. Polymers, 16(20), 2920. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16202920

- Zhang, H., Liu, N., Zeng, Q., Liu, J., Zhang, X., Ge, M., … & Zhang, Y. (2020). Design of polypropylene electret melt blown nonwovens with superior filtration efficiency stability through thermally stimulated charging. Polymers, 12(10), 2341. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym1210234

- Höhnemann, T., Schnebele, J., Arne, W., & Windschiegl, I. (2023). Nanoval Technology—An Intermediate Process between Meltblown and Spunbond. Materials, 16(7), 2932. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16072932