28 Processing Methods for Thermoset Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites

Ruichen Huang

Learning Objectives

By learning this chapter, the readers will have the ability to:

- Describe the fundamental characteristics of thermoset polymers, including viscosity behavior, curing mechanisms, and network formation during composite processing.

- Explain why thermoset polymers are commonly used as matrices in fiber-reinforced composites.

- Describe the main steps involved in common thermoset composite fabrication methods, including hand layup, vacuum bagging, resin infusion, and prepreg/autoclave curing.

- Compare the advantages and limitations of different thermoset polymer composites processing methods.

- Recognize common defects that can occur during processing and understand simple ways to reduce them.

I. Introduction

Fiber-reinforced polymer composites have become indispensable materials in aerospace, automotive, sports equipment, ship structures, and many consumer goods fields. Among various polymer matrices, thermosetting polymers (such as epoxy resins, polyesters, and vinyl esters) are the most commonly used materials in high-performance structural composites. They are so popular because they combine multiple excellent properties: low initial viscosity, good wetting and permeability to fiber-reinforced materials, strong adhesion to fibers, and the ability to form a cross-linked network after curing, providing high strength and dimensional stability.

Thermosetting resins are in a low viscosity liquid state before curing, making them easy to spread, impregnate, and penetrate into fiber fabrics. This is precisely the main reason why they are widely used in composite material manufacturing. After the resin completely wets the reinforcing material, heating or catalysis will trigger a chemical reaction, gradually transforming the liquid resin into a solid three-dimensional network structure. This transformation, namely curing, is the core of all thermosetting composite material processes, and the quality of the final component largely depends on the flowability and curing uniformity of the resin.

In order to fully utilize these characteristics, various manufacturing methods have been developed. Some methods, such as hand lay-up molding and vacuum bag molding, are easy to operate and use, so they are commonly used in teaching and small-scale production. Other methods, such as resin injection molding (vacuum-assisted resin transfer molding/resin transfer molding) and prepreg/autoclave curing, can achieve higher fiber volume fractions, superior mechanical properties, and more stable quality, and are therefore applied in advanced engineering fields. Each method has its own advantages, limitations, equipment requirements, and typical applications, and understanding these differences is crucial for selecting the appropriate composite component manufacturing process.

This chapter will explore the preparation methods of thermosetting composite materials, starting from the basic characteristics of thermosetting polymers and gradually introducing the most commonly used manufacturing methods. This chapter will focus on key concepts such as resin flow, fiber wetting, curing behavior, and common processing defects. After completing this chapter, readers will have a clear understanding of the processing of thermosetting composite materials and be able to choose appropriate manufacturing methods for simple composite components.

II. Key Concepts

1. Basic knowledge of thermoset polymers

Thermosetting polymers are one of the most important matrix materials in fiber-reinforced composites. Unlike thermoplastic materials that soften and flow after heating, thermosetting plastics are initially liquids with relatively low viscosity and are permanently cured through a chemical reaction called solidification. This characteristic makes thermosetting plastics very suitable for processes that require resin to flow into fiber-reinforced materials before curing.

Several common thermosetting resin systems can explain the properties of these materials and the reasons why they are widely used.

Epoxy resin has become the most commonly used material in high-performance composite materials due to its excellent mechanical properties, strong adhesion to fibers, low shrinkage rate during curing, and good environmental resistance. Epoxy resin is usually composed of resin components (such as bisphenol A epoxy resin) and curing agents (amines, anhydrides, etc.), which react to form a dense cross-linked network. Due to its high controllability and predictability, epoxy resin networks are widely used in fields such as aerospace laminates, sports equipment, wind turbine blades, and automotive structural components.[1]

Figure 1: Chemical Structure of Epoxy Resin

Another important type of resin is unsaturated polyester resin, which is commonly used in ship structures, automotive body panels, and consumer goods. Polyester resin is cured through free radical polymerization reaction, usually initiated by styrene monomer. Although polyester resins typically have lower strength and toughness than epoxy resins, they have advantages such as low cost, fast curing speed, and ease of processing. This makes them very suitable for large components or applications that do not require high mechanical performance.

Figure 2: Chemical Structure of Unsaturated Polyester Resin

Vinyl ester resin is between epoxy resin and polyester resin. It is made by reacting epoxy resin molecules with acrylic acid or methacrylic acid to form a mixed chemical structure. Compared with polyester resin, vinyl ester resin has higher toughness and corrosion resistance, while being cheaper and easier to process than epoxy resin. Its balanced performance makes it widely used in fields such as ships, chemical corrosion-resistant equipment, and infrastructure.

Figure 3: Chemical Structure of Vinyl Ester Resin

2. Resin Flow and Fiber Wetting

One of the most important aspects in the processing of thermosetting composite materials is whether the liquid resin can flow smoothly through the fiber-reinforced material before curing. The fluidity of the resin determines the uniformity of the matrix material filling the fiber structure, which directly affects the porosity, stiffness, strength, and reliability of the final composite material. Understanding the flow behavior of resins helps manufacturers choose appropriate processing conditions and avoid common defects.

Before curing begins, thermosetting resins appear as viscous liquids. Viscosity is a key characteristic that determines the ease of resin flow around and within fiber bundles. Low viscosity resins are more popular because they are easier to penetrate into dense fabrics and reduce the likelihood of dry spots. However, viscosity is not constant: it depends on temperature and steadily increases as the curing reaction progresses. If the viscosity rises too fast, gel may occur before the resin completely wets the fiber, resulting in insufficient matrix content in some areas.

Fiber wetting is another key concept. Wetting refers to the ability of liquid resin to spread and adhere to the surface of fibers. Good wettability ensures efficient transfer of load between fibers and matrix, which is crucial for achieving excellent mechanical properties. The wetting quality depends on various factors, including the surface energy of the fibers, the cleanliness of the reinforcing material, and the chemical compatibility of the resin. The pressure applied during processes such as vacuum bag pressing or high-pressure vessel curing can also enhance wettability by pressing resin into small gaps and expelling trapped air.

The interaction between resin fluidity and fiber structure must also be taken into account. Different textiles, such as unidirectional tapes, woven fabrics, and stitched multi-axis reinforcement materials, have varying levels of permeability. Highly dense or tightly woven fabrics may require lower viscosity or longer flow time to achieve full impregnation. Therefore, successful processing of composite materials requires matching the resin properties with the fiber structure and selecting appropriate process parameters.

Figure 4: Wetting Schematic

3. Curing and Network Formation

Curing refers to the chemical process of converting liquid thermosetting resin into a solid cross-linked polymer network. This process is typically activated by heat, catalysts, or initiators and plays a crucial role in determining the performance of the final composite component. Understanding the curing process helps technicians and engineers optimize processing plans, ensuring complete resin impregnation, minimizing residual stress, and achieving expected mechanical properties.

The curing process can be divided into several key stages. In the initial stage, the resin remains liquid and can flow and fully penetrate into the fiber-reinforced material. As the chemical reaction proceeds, the molecular weight increases, leading to a gradual increase in viscosity. This process continues until the resin reaches the gel point, when the resin changes from a viscous liquid to a soft rubber-like solid. After gel, the resin loses its fluidity, which means that any defects or voids in the parts can no longer be repaired.

After gel, the curing process continues with the deepening of network crosslinking. Finally, the system reaches a glassy or fully cured state, at which point the resin has formed most of its mechanical and thermal properties. Curing degree – the proportion of formed chemical bonds – is an important indicator for measuring processing progress. Incomplete curing can lead to a decrease in stiffness, a decrease in glass transition temperature (Tg), and may result in structural failure. On the contrary, curing too quickly can lead to uneven resin distribution, fabric pattern imprints, or excessive internal stress.

Temperature control is crucial throughout the entire curing process. Higher temperatures can reduce early viscosity and promote fluidity, but if not controlled properly, it may also lead to reactions that are too fast. Many processes adopt a staged curing cycle, first performing flowability and wetting treatment at lower temperatures, and then increasing the temperature to complete crosslinking. Understanding curing kinetics, reaction rates, and heat generation can help practitioners design safe and effective process conditions to produce high-quality composite components.

4. Overview of Common Thermoset Composite Processing Methods

Multiple manufacturing methods can be used to make structural composite components from thermosetting resins and fiber-reinforced materials. Each method utilizes the fluidity and curing characteristics of liquid resins in different ways, and each has its own advantages, limitations, equipment requirements, and typical applications.

A widely used method is manual layering combined with vacuum bag molding, which involves manually coating resin onto fabric layers. This method is simple and versatile, suitable for prototyping or small-scale production. The addition of vacuum bags can remove residual air and provide compaction pressure, thereby improving the quality of laminated boards. Although manual layering technology is easy to operate, it is more difficult to operate, and compared to more advanced methods, the fiber volume fraction is usually lower.[2]

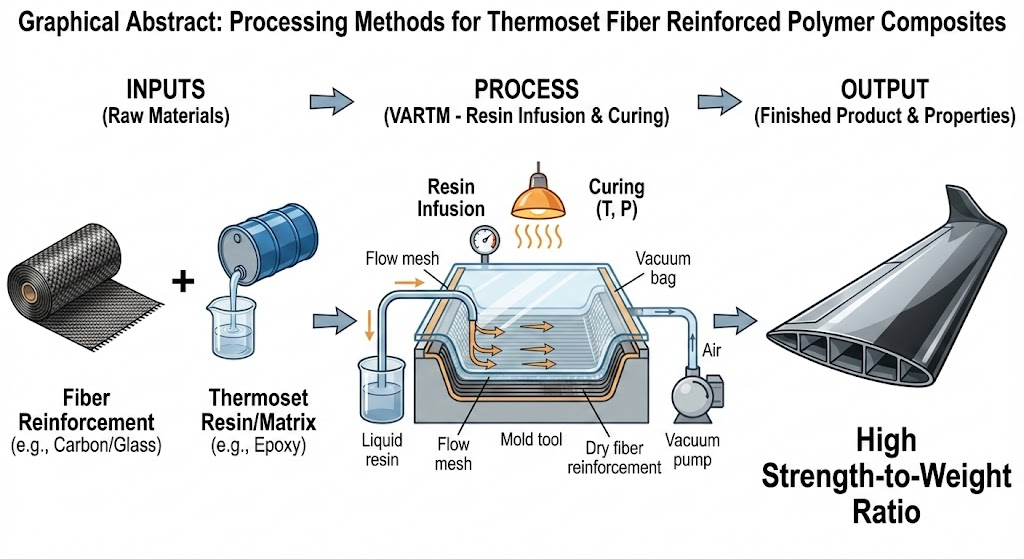

Resin infusion processes, such as vacuum-assisted resin transfer molding (VARTM) and resin transfer molding (RTM), involve placing dry fiber-reinforced materials into a mold and then injecting resin through fiber pulling or injection. These methods can better control resin flow and laminate thickness, making them suitable for manufacturing large components such as ship hulls or wind turbine blades. In addition, a closed mold environment can reduce workers’ exposure to harmful gases and ensure a more stable quality of parts.

Figure 5: Vacuum bag lay-up Schematic

For high-performance applications, prepreg and high-pressure vessel[3] forming processes are commonly used methods. Pre-impregnated fabric is a fabric

pre-impregnated with partially cured resin, which allows for precise control of fiber content and uniform resin distribution. During the processing, multiple layers of prepreg are stacked, vacuum packaged, and then cured in an autoclave. The high temperature and pressure in the autoclave ensure an excellent curing effect and extremely low porosity of the material.[4] The lightweight and high-strength materials produced by this method are widely used in the fields of aerospace structures and sports equipment.

Each processing method requires a balance between cost, equipment availability, material requirements, and required performance. Understanding how resin flow, wetting, and curing affect each method can help select appropriate processing strategies for different composite material designs.

III. Related Paper Discussion

Article:

Coppola, A. M., Huelskamp, S. R., Tanner, C., Rapking, D., & Ricchi, R. D. (2023). Application of tailored fiber placement to fabricate automotive composite components with complex geometries. Composite Structures, 313, 116855. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPSTRUCT.2023.116855

1. Research Overview

This article investigates the application of Custom Fiber Placement (TFP) technology, a robot traction and stitching technique, in the manufacturing of automotive component linkages with extremely high structural requirements. Traditionally, connecting rods are metal components that bear enormous cyclic loads during engine operation. Replacing metal components with composite materials requires high strength, low weight, excellent fatigue resistance, and the ability to process complex curved geometries. The author chose TFP technology because it can accurately guide fiber bundles along the optimal load path, which traditional unidirectional or woven fabrics cannot achieve.

This study involves multiple stages: modeling the load environment of the connecting rod, designing fiber trajectories based on the direction of principal stress, preparing multi-layer TFP preforms, using a high-temperature bismaleimide thermosetting resin system for resin transfer molding (RTM), subsequent mechanical processing, and tensile, compressive, and fatigue mechanical testing. This article aims to evaluate the structural performance and verify whether the TFP preform is compatible with the RTM processing method, as well as whether the quality of the resulting laminated board is sufficient to meet the high fatigue performance requirements of automotive applications.

This study has significant value for education as it integrates pre-molding, resin infusion, thermosetting resin curing, laminate consolidation, and mechanical properties into a coherent experimental process. It provides students with a real-life case that demonstrates how decisions made during the preform design and process selection process affect the final performance of composite structures.

From a processing perspective, the paper demonstrates how the characteristics of thermoset matrices—particularly flow behavior, curing kinetics, and network formation—interact with complex textile preforms to produce the final structural laminate. In this study, the selected resin was Cycom 5240-4 bismaleimide, chosen for its ability to withstand high service temperatures and deliver excellent compression performance. Bismaleimide resins are relatively brittle compared to epoxy resins, but their superior hot-wet stability and heat resistance make them attractive for aerospace-grade or engine-adjacent components. These features strongly influence the mechanical results reported in the study, especially in fatigue.

This article also focuses on the role of resin transfer molding (RTM) as a processing method for thermosetting materials. RTM requires the resin to flow uniformly through the dried fiber preform, which means that the permeability, stitching porosity, and fiber bundle compaction of the preform directly affect the distribution of the resin. After injection, the resin will go through a multi-stage curing cycle, including flow, gel, crosslinking and post curing. The author describes mold preheating, resin preheating and staged curing, emphasizing the importance of controlling viscosity and curing kinetics to avoid premature gelation or uneven flow.

Importantly, this study reinforces an important educational message: thermosetting resin processing cannot solve upstream design problems. If the structure of the preform has weak interfaces or insufficient reinforcement in the thickness direction, voids or delamination may form during the flow or solidification process. Even after complete curing, these defects can still seriously affect the mechanical properties of the material.

2. Key Results Analysis

One striking finding is the connecting rod’s exceptional tensile performance, achieving 90.2 kN, more than seven times the design requirement. This is attributed to the high fiber volume fraction and the ability of TFP to align fibers directly along the tensile load path, improving load transfer efficiency. The thermoset matrix provided good fiber bonding, enabling the laminate to fully utilize the strength of the carbon fibers.

In compression, the part achieved 74.8 kN, exceeding the target value by 45%. Compression failures tended to occur in regions where fiber curvature induced local instability or where stitching patterns produced resin-rich pockets. While still strong, compression performance revealed how local variations in fiber steering and laminate consolidation can influence buckling and local crushing behavior.

Figure 6: Visible damage in connecting rods following monotonic testing for a) compression sample 1, b) compression sample 2, c) tension sample 1, and d) tension sample[5]

Fatigue performance, however, was significantly limited. At the required automotive cyclic load of 64.5 kN, the connecting rods failed at 417 and 172 cycles, far below the long-life design target. The authors systematically lowered the load until specimens survived over one million cycles, which occurred only at 26 kN, a much lower stress range.

Micrographs and CT scans revealed that delaminations consistently originated at the interfaces between sub-preforms, where there was reduced through-thickness reinforcement and weaker resin bonding. These interfaces provided easy pathways for crack initiation and propagation. Furthermore, regions around the small-end hole experienced multi-axial stresses that led to fiber breakage and crushing.

This result is a powerful illustration of how processing-induced features, such as discontinuous stitching or insufficient z-support, compromise fatigue performance even when monotonic strengths are high.

Graphical Abstract

References

- Kausar, A. (2017). Role of Thermosetting Polymer in Structural Composite. Role of Thermosetting Polymer in Structural Composite.

- Shen R, Liu T, Liu H, Zou X, Gong Y, Guo H. An Enhanced Vacuum-Assisted Resin Transfer Molding Process and Its Pressure Effect on Resin Infusion Behavior and Composite Material Performance. Polymers (Basel). 2024 May 13;16(10):1386.

- Falzon, B.G., Pierce, R.S. (2020). Thermosetting Composite Materials in Aerostructures. In: Pantelakis, S., Tserpes, K. (eds) Revolutionizing Aircraft Materials and Processes. Springer, Cham.

-

Struzziero, G., Teuwen, J. J. E., & Skordos, A. A. (2019). Numerical optimisation of thermoset composites manufacturing processes: A review. In Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing (Vol. 124). Elsevier Ltd.

-

Coppola, A. M., Huelskamp, S. R., Tanner, C., Rapking, D., & Ricchi, R. D. (2023). Application of tailored fiber placement to fabricate automotive composite components with complex geometries. Composite Structures, 313, 116855.