12 From Solution Thermodynamics to Solid-State Mechanics

murier Lyu

1. Introduction

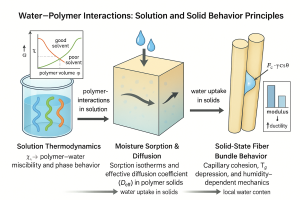

Water is one of the most important “secondary components” in polymer systems. Even when present only as ambient humidity, water can alter processing, structure development, and in-service performance of polymer materials. Depending on chemistry and morphology, water may behave as a true solvent, a swelling agent in crosslinked networks, or a powerful plasticizer for glassy matrices.¹⁻³

At the molecular level, polar groups (e.g., hydroxyl, ether, amide) form hydrogen bonds with water, giving rise to bound water with restricted mobility and free or loosely bound water residing in microvoids.² Bound water strongly affects local dynamics and glass transition temperature Tg, while free water controls swelling and transport. In engineering polymers used for coatings, adhesives, electronic encapsulants, textiles, and 3D-printing filaments, these moisture-induced changes can manifest as shifts in modulus and strength, dimensional instability, interfacial debonding, and even catastrophic failure.²,³

Understanding water–polymer interactions therefore requires a multi-scale viewpoint:

-

solution thermodynamics (polymer–water miscibility, interaction parameter χ);

-

sorption and diffusion in the solid state;

-

coupled moisture–mechanical behavior, including capillary effects in fiber bundles and granular assemblies.

This chapter provides an integrated overview of these aspects with emphasis on concepts that are broadly useful for polymer solution and solid behavior principles.

Suggested Video Resource

To complement this chapter, you are encouraged to watch the YouTube video “How Does Moisture Affect Polymer Composites?” . This short popular-science style video explains how water enters polymer composites and changes their mechanical properties, reinforcing the concepts of moisture sorption, plasticization, and degradation discussed later in the chapter.

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, students should be able to:

-

Describe the roles of water as solvent, plasticizer, and swelling agent in polymer systems, and distinguish bound from free water in polymer matrices.

-

Apply basic solution thermodynamics (Flory–Huggins interaction parameter χ, solubility concepts) to interpret polymer–water miscibility and phase behavior.

-

Interpret moisture sorption isotherms and analyze diffusion-controlled uptake using Fickian and non-Fickian descriptions.

-

Explain how water uptake modifies Tg, modulus, strength, and dimensional stability in polymers, and relate these changes to molecular interactions and morphology.

-

Discuss the role of capillary bridges and liquid-mediated cohesion in wet granular and fiber-bundle systems, and connect these concepts to the mechanical response of wet fibers and yarns.

2. Solution Thermodynamics of Polymer–Water Systems

Polymer–water miscibility and the Flory–Huggins parameter.

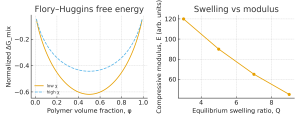

In the liquid state, miscibility of a polymer with water is often analyzed using Flory–Huggins solution theory. The free energy of mixing combines combinatorial entropy with an enthalpic term governed by the interaction parameter χ. For small χ, the free-energy curve ΔGₘᵢₓ(φ) has a single minimum and polymer and water are miscible over a wide composition range. As χ increases, the curve develops two minima separated by a maximum, signaling a tendency toward liquid–liquid phase separation and polymer-rich/water-rich domains.¹,²

From a design point of view, χ encapsulates how “comfortable” the polymer segments are in water. A low χ promotes homogeneous solutions or highly swollen gels; a high χ promotes precipitation, opalescence, or sharp cloud points. For many systems, χ is temperature- and composition-dependent, which explains why polymer–water mixtures can exhibit upper or lower critical solution temperatures (UCST/LCST). Thermoresponsive hydrogels such as poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) in water are classical LCST examples: soluble at low temperature, but phase-separating upon heating as effective χ increases.²

Determining χ\chiχ from swelling and mechanics.

Direct calorimetric determination of χ is possible but demanding. A practically useful strategy is to infer χ from equilibrium swelling and mechanical response of hydrogels. Akalp et al. combined swelling ratios, compressive moduli, and a self-learning inverse algorithm to obtain χ(T) for PEG hydrogels in water, showing that χ\chiχ depends on cross-link density, degradation, and processing.¹ This approach explicitly links solution thermodynamics to solid-state elasticity and provides a blueprint for characterizing other polymer–water systems.

3. Moisture Sorption and Diffusion in Polymers

Sorption isotherms.

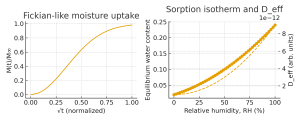

Once the polymer is in the solid state, water uptake is described by sorption isotherms relating activity (or relative humidity, RH) to equilibrium water content. At low water contents, a Henry-type linear regime is often observed, corresponding to dissolution of water in free volume. As RH increases, Langmuir-type site saturation at specific polar sites and eventual water clustering lead to non-linear isotherms. Widely used dual-mode sorption models combine Henry and Langmuir terms to describe glassy polymers, barrier films, and hydrogels.²

For practical materials (e.g., epoxy encapsulants, polyamides, high-performance composites), sorption isotherms are rarely perfectly reversible. Hysteresis between sorption and desorption reflects microstructural rearrangements, physical aging, or microcracking induced by repeated swelling/drying.² These features complicate lifetime predictions because the “effective” moisture state depends on history, not just the current environment.

Diffusion kinetics: Fickian and non-Fickian behavior.

The time dependence of water uptake is commonly analyzed with Fick’s laws. For simple Fickian diffusion in a slab, a plot of normalized mass gain vs √t yields an initial linear region whose slope is related to the effective diffusion coefficient Deff²,³ Many engineering handbooks still assume a constant Deff and purely Fickian behavior for simplicity.

However, experiments reveal a wide range of non-Fickian (anomalous) behaviors:

-

two-stage uptake with a fast initial regime followed by slow relaxation;

-

apparent overshoot where mass gain exceeds the final equilibrium value before relaxing back;

-

thickness- or temperature-dependent exponents in empirical M(t) ∝ tⁿ fits.²

Yang et al. systematically reviewed such behaviors, emphasizing that coupling between molecular diffusion and polymer relaxation is key to understanding non-Fickian transport.² For example, in glassy polymers near Tg, chain segments relax on similar time scales as water penetrates, leading to complex kinetics that cannot be captured by a single constant Deff .

Mechanics-of-moisture perspective.

Fan highlighted that for engineering applications (e.g., electronics encapsulation) it is not enough to know just a single Deff .³ Moisture transport is often concentration-dependent, can involve surface resistance, and must be coupled with swelling and mechanical deformation. His mechanics-of-moisture framework extends Fick’s law with concentration-dependent diffusivity and viscoelastic constitutive equations, enabling realistic simulations of package warpage and cracking under humid conditions.³

4. Coupled Moisture–Mechanical and Capillary Effects in Fiber Bundles

Plasticization and swelling of the polymer phase.

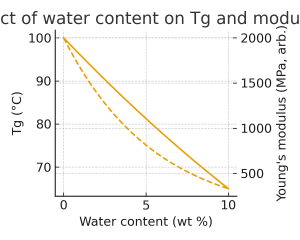

Moisture affects solid-state behavior primarily via plasticization and swelling. Water molecules weaken intermolecular interactions and increase free volume, leading to a reduction in Tg and modulus and often an increase in ductility and toughness.¹⁻³ Non-uniform moisture profiles generate swelling gradients and internal stresses, which can cause warpage, microcracking, or interfacial debonding, especially in multilayer systems.³ In fiber-based materials (paper, textiles, cellulosic composites), swelling may be anisotropic, with larger expansion transverse to the fiber axis than along it, further complicating dimensional stability.

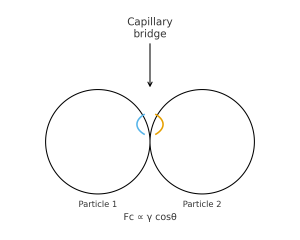

Capillary bridges and additional cohesion.

Beyond dissolved water in the polymer bulk, condensed liquid at contact points can form capillary bridges between particles or fibers. Kohonen et al. studied model wet granular materials consisting of glass beads and showed that even very small liquid contents result in a network of microscopic bridges whose geometry (bridge volume, curvature radii, contact angle) determines the capillary force Fc.⁴ This attractive force, scaling with surface tension γ\gammaγ and contact angle θ, significantly increases the apparent cohesion and yield stress of the material.

Kovalcinova et al. extended this concept by simulating sheared dry and wet granular assemblies under confining pressure.⁵ They found that in wet systems, energy dissipation arises not only from frictional sliding but also from stretching and rupture of capillary bridges. At low confining pressures, the wet assembly exhibits higher apparent stiffness and yield stress than the dry one because capillary forces dominate over normal loads.

By analogy, in wet fiber bundles (e.g., cellulosic yarns, glass rovings with a small amount of water), capillary bridges between neighboring filaments can dominate the interfiber cohesion:

-

at low to moderate water contents, bridges enhance contact area and normal load, increasing bundle stiffness and strength;

-

at higher water contents, strong plasticization and swelling of the fibers and interphases may reduce overall modulus and promote creep, despite stronger cohesion.

The net mechanical response is thus a balance between capillary cohesion and moisture-induced softening of the polymer phase.

5. Summary

Water–polymer interactions span multiple scales, from molecular solution thermodynamics to macroscopic mechanical response in fiber assemblies. In solution, the Flory–Huggins parameter χ provides a compact way to describe polymer–water miscibility and phase behavior, and can be inferred from swelling and mechanical data of gels. In the solid state, moisture sorption isotherms and diffusion kinetics govern how quickly and how much water is taken up, while plasticization and swelling control changes in Tg, modulus, and dimensional stability.

In heterogeneous systems such as fiber bundles and granular assemblies, liquid water also forms capillary bridges that dramatically alter cohesion and energy dissipation. The overall behavior of wet materials therefore reflects a combination of bulk plasticization, swelling stresses, and capillary forces. A quantitative understanding of these coupled processes is essential for designing polymer systems and textile structures that operate reliably in humid or aqueous environments.

References

-

Akalp, U.; Chu, S.; Skaalure, S. C.; Bryant, S. J.; Doostan, A.; Vernerey, F. J. Determination of the Polymer–Solvent Interaction Parameter for PEG Hydrogels in Water: Application of a Self Learning Algorithm. Polymer 2015, 66, 135–147.

-

Yang, C.; Xing, X.; Li, Z. A Comprehensive Review on Water Diffusion in Polymers Focusing on the Polymer–Metal Interface Combination. Polymers 2020, 12 (1), 138.

-

Fan, X. Mechanics of Moisture for Polymers: Fundamental Concepts and Model Study. In EuroSimE 2008 – International Conference on Thermal, Mechanical and Multi-Physics Simulation and Experiments in Micro-Electronics and Micro-Systems; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, 2008; pp 1–10.

-

Kohonen, M. M.; Geromichalos, D.; Scheel, M.; Herminghaus, S. On Capillary Bridges in Wet Granular Materials. Physica A 2004, 339 (1–2), 7–15.

-

Kovalcinova, L.; Karmakar, S.; Schaber, M.; Schuhmacher, A.-L.; Scheel, M.; Di Michiel, M.; Brinkmann, M.; Seemann, R.; Kondic, L. Energy Dissipation in Sheared Wet Granular Assemblies. Phys. Rev. E 2018, 98 (3), 032905.