6 Connecting community

North Carolina lost four daily newspapers between 2004 and 2019, and 44 newspapers total, according to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media. Go to the site and see how many papers your state or region has lost.

You’ve read about how community ties are facilitated by local newspapers, TV and radio stations. So, what happens in a community when there is an absence of news of any kind?

Not surprisingly, it creates problems. We know because even thriving news organizations have sometimes ignored segments of the communities they cover. Black communities in the United States are among those long ignored by the mainstream press. While the problem goes back much further, early events in the Civil Rights movement provide examples of the lack of media attention and what is lost as a result.

Most people familiar with 20th century American history know Rosa Parks ignited change in Montgomery, Alabama, and the nation, by refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger on a segregated city bus.

That action in 1955 sparked a bus boycott that was publicized in the Black community through leaflets, then gained the attention of the local paper, the Montgomery Advertiser, and national news media. Parks’ actions not only changed public transportation in Montgomery, they lead to the 1964 federal Civil Rights Act that banned racial discrimination in public accommodations.

Martin Luther King Jr. later said, “(Editor) Joe (Azbell) and the Advertiser printing that on the front page on Sunday morning was a greater impetus for the success of the boycott than anything before.” Advertiser reporter Bob Ingram recalled King’s statement in a story commemorating the boycott’s 50th anniversary in 2005.

The reason King said that, Ingram learned, was a problem spreading the word within Montgomery’s Black community about a protest that eventually would take on a life of its own and become not only a national story, but the start of the modern civil rights movement.

Less known is a bus boycott about 90 miles away in Birmingham, Alabama, that overlapped with Montgomery’s. Birmingham civil rights activists protested bus segregation there with boycotts in 1956. But national and local news media ignored the Birmingham events, according to Howell Raines in his oral Civil Rights history, “My Soul is Rested.”

Instead of great social change, as was prompted in Montgomery, 500 Black Birmingham citizens were jailed, and reprisals including evictions, firings and bombings were the result of the boycotts there.

In Montgomery, community ties—supported by local newspaper and TV coverage—resulted in a world-renowned and very successful boycott. In Birmingham, where efforts of protesters were not covered by community (or national) media, the boycott was unsuccessful and bombings continued well into the 1960s.

A sense of community, a feeling of self-worth and a way to escape oppression are crucial to the successful functioning of communities. When minority issues, events and people are not served by mainstream (or any other) media, those communities are not afforded this facilitator of community ties. And, as King observed in Montgomery, leaflets alone won’t get the message out.

With local media reporting on them, communities are better able to maintain, improve and support themselves by allowing members to see their issues depicted and discussed. This extends those personal and social contacts. It builds consensus on issues. This is especially true for minority communities. And, as illustrated in Birmingham, it is especially damaging when these issues are ignored.

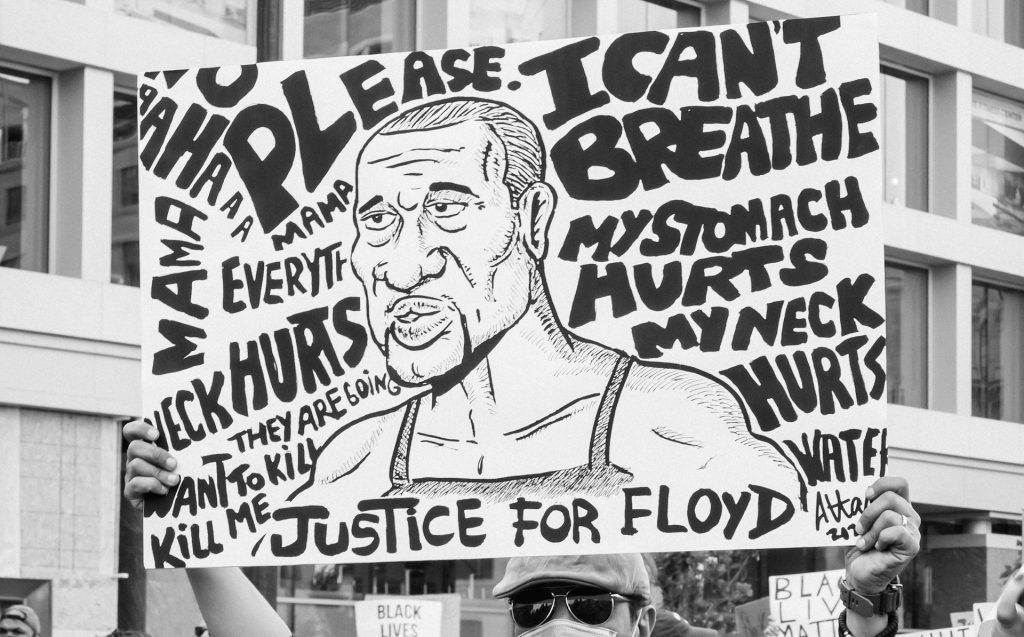

Local news media, both TV and print, can function as an agent of community welfare and progress not only as a whole, but for groups within the larger community. Especially marginalized ones. This is just as true during the Black Lives Matter era as it was during the early years of the Civil Rights Era.

Coverage of the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, Breonna Taylor in Kentucky, and most prominently, George Floyd in Minnesota, have been opportunities for news media to shine a spotlight on deaths of Black Americans at the hands of police and others. The results have included a national reckoning on the issue of police brutality and belated attention to the ways Black citizens are treated by law enforcement and the courts. Citizens created the Black Lives Matter movement, and media coverage stoked it.

But here, disinformation played a role as well. The intense media attention to Floyd’s death was accompanied by misinformation and the spread of conspiracy theories.

A rumor that Floyd hadn’t been killed was circulated on a YouTube conspiracy channel. The video was later removed. The phrase “George Floyd is not dead” gained traction on Twitter. Fox News, among other conservatively biased television media, defended the police officer involved in Floyd’s death and blamed Floyd himself for having drugs in his system. This makes it even more important that legitimate news outlets cover the events fairly, factually and fully. The truthful reporting of Floyd’s death, as well as the deaths of others in similar situations, helps thwart the impact of those seeking to misrepresent or twist the facts.

Diverse Viewpoints On and Around Campus

Despite the false and misleading information, 72 percent of black adults called the mainstream news media’s coverage of the Floyd protests good or excellent, according to the Pew Research Center. This is a reminder that accurate coverage of issues that impact minority communities can be helpful in the ways mentioned above.

College campuses are no exception. A 2019 Auburn Plainsman story by Eduardo Medina looked at how new student housing built near Auburn University’s campus was gentrifying historically Black neighborhoods and forcing older Black residents out.

The story began to develop when Medina, as assistant community editor for The Auburn Plainsman, first noticed new construction and found it odd that student housing was being built in lower-income neighborhoods. He later told student journalists at North Carolina State University he was motivated to explore how the local residents felt about this happening in their neighborhoods.

Medina’s Auburn Plainsman story won first place for best in-depth news story from the Associated Collegiate Press for illustrating the difficult position development and gentrification put long-time Auburn residents. Medina’s reporting revealed city decision-makers more focused on profit than the lives and needs of those who had lived in the area for years. More broadly, the story fulfilled the mission of the journalist to hold the powerful accountable and give voice to the voiceless.

The powerful may not appreciate it, but Black and Hispanic citizens said in one survey it is extremely important for journalists to offer solutions to community problems. How can reporters and editors do this? There are several ways to report on communities other than your own and respond effectively to the issues members face by doing exactly what Medina did in Auburn. His story shows how well they can work.

- Invest the time to learn more about various communities and the individuals who inhabit them.

- Spend time in those communities.

- Connect to members of communities other than your own through social media.

- Question your own worldview.

Doing these things takes work and time. Medina told student journalist Amber Doyle he first thought the story would focus on one source, Veira Collins. But as he made more trips to the neighborhood, other people approached him, willing to talk about the issues. He called it “building trust” with the sources.

Chapter 6: Questions to Consider

How can stories be more engaging and relevant to all demographic groups in society? Why?

Are all groups represented in news you have read, watched or heard? If not, who is missing?

What’s the connection between journalists holding the powerful accountable and being called “enemies of the people”?

Media Attributions

- 960px-Rosa_parks_human_rights_museum_memphis_2

- gayatri-malhotra-oPzSBTqbKFU-unsplash