13 Navigating information overload

Let’s go back in time. You’re in a college journalism class, 1986. The professor asks, “Where do you get your news?” You look around at the teased hair and the parachute pants of your classmates. How will they answer? It’s not too difficult to puzzle out. Here are the options:

- National TV news: the ABC, CBS or NBC daily half-hour evening newscasts. Six-year-old CNN if you have cable. (Many dorms don’t.) “60 Minutes” Sundays on CBS. “20/20” Thursdays on ABC. “The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour” weeknights on PBS.

- One of the local daily newspapers: It’s 1986, so many larger cities have at least two. Smaller college towns are more likely to have just one.

- Local TV news: in larger cities, the ABC, CBS or NBC affiliates typically broadcast two half-hour newscasts in early and late evening. They air simultaneously, so only one can be watched at a time.

- National Public Radio news: In most college towns and big cities, you can listen to the morning and late afternoon news programs on local public stations.

- A few other options: The weekly news magazines Time, Newsweek and U.S. News. Subscriptions to bigger-city newspapers that would come in the mail several days after publication or could be found in the campus library. Some bigger-city commercial radio stations have an all-news format.

That’s not nothing.

But it’s a short list compared to the options today’s college students have. The same question this year illustrates the many, many options that didn’t exist in 1986 including expanded cable or TV news options Fox News, MSNBC and, for most Americans, BBC World News.

While the number of newspapers has declined and news magazines have lost their clout since 1986, the overall impact of newspapers and magazines has increased because almost every newspaper and magazine in the world is available in real-time online. Similarly, stories from every network news affiliate.

In addition to the increase in access to media outlets that were once only available locally, there’s the added dimension of online-only news sources, including blogs, podcasts and vlogs. There are news aggregators including Drudge Report, HuffPost and The Daily Beast. News also pops up in Web searches and on social media platforms. That’s why, when the question “Where do you get your news?” is asked today, some students invariably answer, “Google.”

Google, X and Instagram Are Not News Sources

Like in-house news sources, this is another point of confusion for some news consumers. News on Google and X is often detached from its original source. This makes determining the credibility of the source more difficult. And even if every news story a person reads on X is from a credible news source, getting news this way is far from comprehensive.

What’s posted to social media depends on who’s doing the posting. What shows up in a search depends on what they’re searching for. As a result, getting news from X, Instagram or Google leaves news consumers with huge information gaps, making it unlikely they have an accurate sense of what is going on nearby or in the larger world. On Instagram, when someone posts something newsworthy, it disappears after 24 hours.

The Valencia College library guide to “fake news” says, despite being a powerful search tool, Google is limited for those looking for information. Specifically, it can “deliver false and misleading sites in its search results.” The Valencia College guide cites three characteristics of Google that make it an unreliable information source.

- Its algorithms can be manipulated. This is especially problematic when disinformation games the algorithms.

- A phenomenon called “filter bubbles” causes an Internet user to encounter only information and opinions that comply with—and reinforce—his or her already-existing beliefs. Filter bubbles are created, again, by algorithms.

- Google has no editorial process. Unlike editors at your local newspaper, no one monitors the quality or accuracy of what you find there.

Disinformation Isn’t New

This is a kind of triple whammy for students in journalism class today as well as readers in general. Not only did audiences have less access to media in 1986, only a small percentage of what was accessible peddled in disinformation and biased news. Plus, there was no such thing as Google or X pushing that small percentage of misleading information out to the masses.

What we have now is a convergence of the best and worst of two worlds. We have access to more information than ever before. So much so, some call this the Communication Age of human history (the modern version of the Stone, Bronze and Iron ages). That’s the good news. The downside is, one person with a computer can misinform thousands.

Radio Priest

To be clear, this isn’t to say there were no disinformation before Google came along. In the 1930s, Father Charles Coughlin was known as “the radio priest,” preaching to an audience of 90 million. His weekly magazine, Social Justice, had a circulation of a million, according to the New York Times. His messages were frequently anti-Semitic and pro-facist.

Tabloids

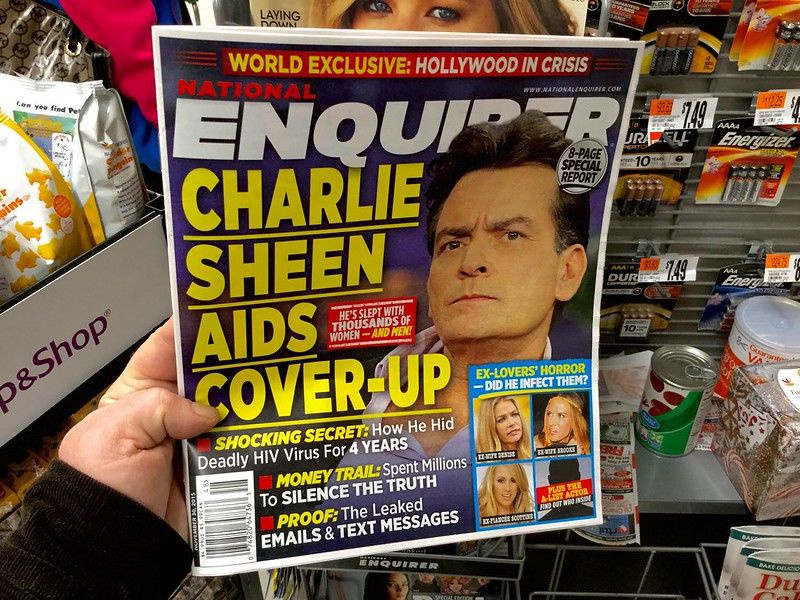

Before Google, everyone who went to a grocery store was confronted by disinformation and misleading news in the form of so-called “supermarket tabloids” like The National Enquirer and the Weekly World News. The Wikipedia entry on the Sun tabloid shows an edition with the headline “DaVinci Code is For Real!” The Weekly World News’ series of headlines about Bat Boy inspired an off-Broadway play, “Bat Boy: The Musical.” When The National Enquirer reported TV comedian Carol Burnett had a drunken confrontation with the U.S. secretary of state, she sued and won by proving the tabloid’s editors knew the story was untrue.

Political Talk Radio

After the repeal of the Federal Communication Commission’s Fairness Doctrine in 1987, politically oriented talk radio broadcasts proliferated. The Fairness Doctrine was also sometimes called the “equal-time law” because it stipulated, in part, that radio and TV stations had to provide equal air time to all candidates for public office. Additionally, if one side of an issue was presented on air, the other side had to be presented as well. Without that provision, commentators like Rush Limbaugh were free to present news as they saw it. Limbaugh had as many as 15 million weekly listeners at his peak.

But now these formerly isolated forces have gained strength through the net. Limbaugh’s success led to dozens of other political talk show commentators. Bill O’Reilly and Sean Hannity migrated from radio to television with the founding of Fox News in 1996. TMZ reporters follow celebrities all over the world with cameras in hand. TMZ has morphed from a celebrity-news website to now include livestreaming shows and a syndicated television program. Anyone in the world can post celebrity sightings to the Instagram account @Deuxmoi.

So, disinformation isn’t new. Neither is biased news, slanted news, unsubstantiated news and satire. What does it matter? It matters because it has gone from the grocery store checkout stands to possibly impacting the 2016 presidential election won by Donald Trump and later playing a role at the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

In the Journal of Economic Perspectives, economic researchers Hunt Allcott and Matthew Gentzkow show that voters’ exposure to “fake news” stories was high in 2016 and had the potential to sway the election. Among the disinformational stories, they cite as part of their research is the Denver Guardian story from Chapter 1 that falsely connects Hillary Clinton to a murder-suicide. That story is also on a list the business news channel CNBC published in 2016 of the biggest “fake news” stories of that year.

In addition to the “Denver Guardian” story, the list included:

“Pope Francis shocks world, endorses Donald Trump for president” from the “fake news” site WTOE 5 News.

The “pizzagate” conspiracy theory that connected Democrats to a child-sex ring operated from a Washington D.C pizza restaurant. It originated in online communities 4chan and Reddit, according to CNBC.

“ISIS leader calls for American Muslim voters to support Hillary Clinton” from “fake news” site WNDR.

“Donald Trump sent his own plane to transport 200 stranded marines,” was traced back to Sean Hannity’s website, Hannity.com. This story is a transitional one on the list because in it, disinformation and politically biased news merge. Hannity, of course, is the radio commentator who also hosts a nightly Fox News TV program. In cases like this, there is a thin line between “fake news” and biased news.

Print and Television News

When citizens of all political persuasions criticize fake and biased news (and understandably conflate the two), they often fail to differentiate between print and broadcast news. So, take note: There’s a big difference. In the United States, TV stations and newspapers that reports local, state and national news are uniformly responsible, reliable and without overt bias in their news reporting.

The 24-hour news channels are much less so. It’s the so-called cable news channels that report from political perspectives and often promote one party at the expense of another. So, if someone tells you “all media” do what Fox News or MSNBC do, it’s simply not true. Remember, the media are not a monolith.

Chapter 13: Questions to Consider

What role does advertising play in some TV news networks’ decisions to slant news in favor of one political party or another?

The BBC’s content is much more politically neutral than Fox News and MSNBC. Why?

@Deuxmoi’s bio says “statements made on this account have not been independently confirmed.” How does that impact the site’s trustworthiness?

Why are in-house sports websites less likely to cover social issues?

Media Attributions

- 22771236287_98e6f63eb8_c