Two of the four general carbonyl-group reactions—carbonyl condensations and α substitutions—take place under basic conditions and involve enolate-ion intermediates. Because the experimental conditions for the two reactions are similar, how can we predict which will occur in a given case? When we generate an enolate ion with the intention of carrying out an α alkylation, how can we be sure that a carbonyl condensation reaction won’t occur instead?

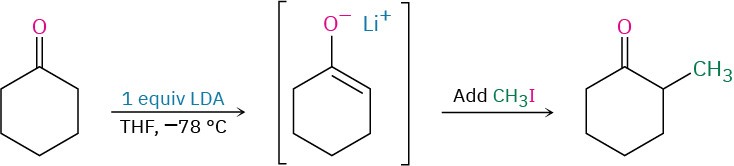

There is no simple answer to this question, but the exact experimental conditions usually have much to do with the result. Alpha-substitution reactions require a full equivalent of strong base and are normally carried out so that the carbonyl compound is rapidly and completely converted into its enolate ion at a low temperature. An electrophile is then added rapidly to ensure that the reactive enolate ion is quenched quickly. In a ketone alkylation reaction, for instance, we might use 1 equivalent of lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) in tetrahydrofuran solution at –78 °C. Rapid and complete generation of the ketone enolate ion would occur, and no unreacted ketone would remain, meaning that no condensation reaction could take place. We would then immediately add an alkyl halide to complete the alkylation reaction.

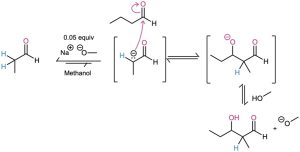

On the other hand, carbonyl condensation reactions require only a catalytic amount of a relatively weak base, rather than a full equivalent, so that a small amount of enolate ion is generated in the presence of unreacted carbonyl compound. Once a condensation occurs, the basic catalyst is regenerated. To carry out an aldol reaction on propanal, for instance, we might dissolve the aldehyde in methanol, add 0.05 equivalent of sodium methoxide, and then warm the mixture to give the aldol product.