Now that we know how SN2 reactions occur, we need to see how they can be used and what variables affect them. Some SN2 reactions are fast, and some are slow; some take place in high yield and others in low yield. Understanding the factors involved can be of tremendous value. Let’s begin by recalling a few things about reaction rates in general.

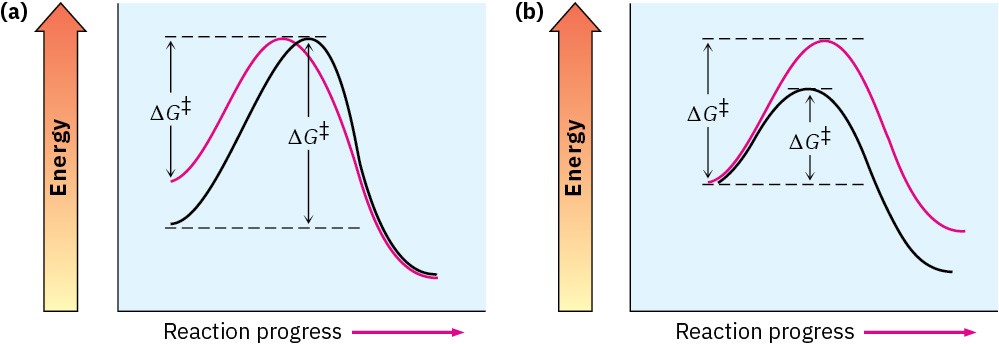

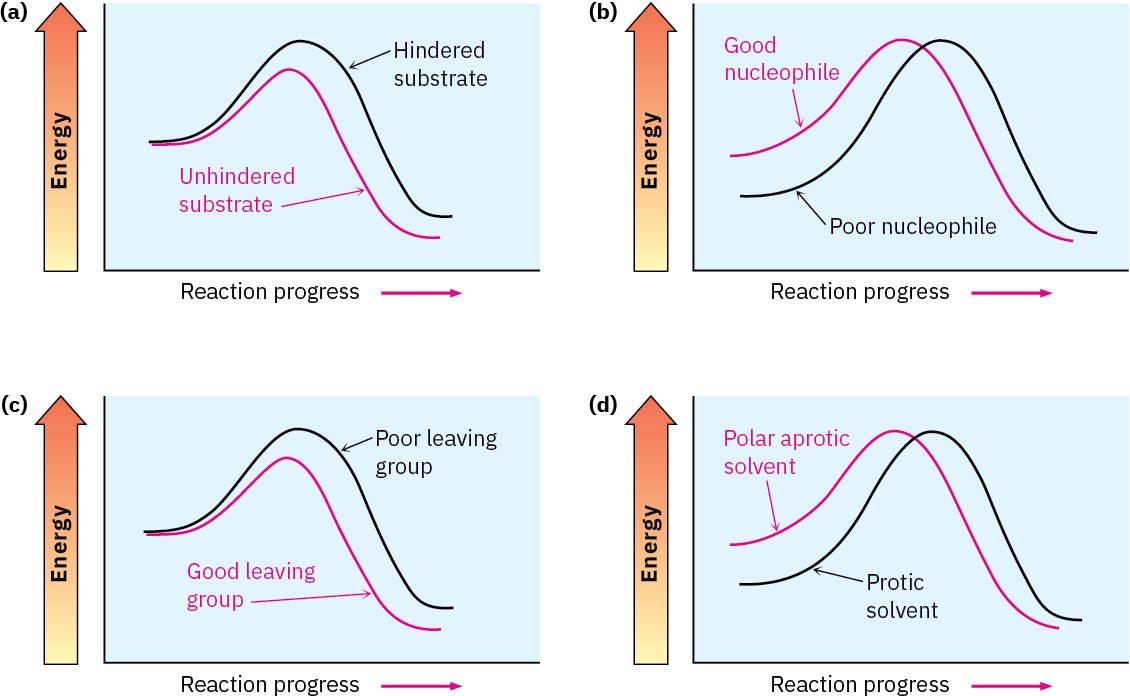

The rate of a chemical reaction is determined by the activation energy ∆G‡, the energy difference between reactant ground state and transition state. A change in reaction conditions can affect ∆G‡ either by changing the reactant energy level or by changing the transition-state energy level. Lowering the reactant energy or raising the transition-state energy increases ∆G‡ and decreases the reaction rate; raising the reactant energy or decreasing the transition-state energy decreases ∆G‡ and increases the reaction rate (Figure 11.6). We’ll see examples of all these effects as we look at SN2 reaction variables.

Figure 11.6 The effects of changes in reactant and transition-state energy levels on reaction rate. (a) A higher reactant energy level (red curve) corresponds to a faster reaction (smaller ∆G‡). (b) A higher transition-state energy level (red curve) corresponds to a slower reaction (larger ∆G‡).

Steric Effects in the SN2 Reaction

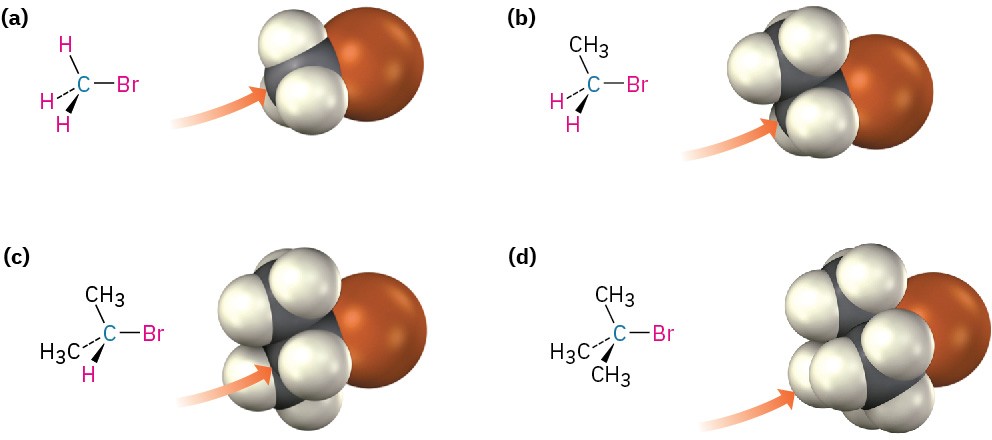

The first SN2 reaction variable to look at is the structure of the substrate. Because the SN2 transition state involves partial bond formation between the incoming nucleophile and the alkyl halide carbon atom, it seems reasonable that a hindered, bulky substrate should prevent easy approach of the nucleophile, making bond formation difficult. In other words, the transition state for reaction of a sterically hindered substrate, whose carbon atom is “shielded” from the approach of the incoming nucleophile, is higher in energy and forms more slowly than the corresponding transition state for a less hindered substrate (Figure 11.7).

Figure 11.7 Steric hindrance to the SN2 reaction. As the models indicate, the carbon atom in (a) bromomethane is readily accessible, resulting in a fast SN2 reaction. The carbon atoms in (b) bromoethane (primary), (c) 2-bromopropane (secondary), and (d) 2-bromo- 2-methylpropane (tertiary) are successively more hindered, resulting in successively slower SN2 reactions.

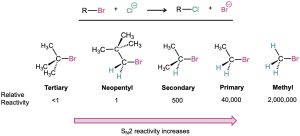

As Figure 11.7 shows, the difficulty of nucleophile approach increases as the three substituents bonded to the halo-substituted carbon atom increase in size. Methyl halides are by far the most reactive substrates in SN2 reactions, followed by primary alkyl halides such as ethyl and propyl. Alkyl branching at the reacting center, as in isopropyl halides (2°), slows the reaction greatly, and further branching, as in tert-butyl halides (3°), effectively halts the reaction. Even branching one carbon away from the reacting center, as in 2,2- dimethylpropyl (neopentyl) halides, greatly hinders nucleophilic displacement. As a result, SN2 reactions occur only at relatively unhindered sites and are normally useful only with methyl halides, primary halides, and a few simple secondary halides. Relative reactivities for some different substrates are as follows:

Vinylic halides (R2C═CRX) and aryl halides are not shown on this reactivity list because they are unreactive toward SN2 displacement. This lack of reactivity is due to steric factors: the incoming nucleophile would have to approach in the plane of the carbon–carbon double bond and burrow through part of the molecule to carry out a backside displacement.

The Nucleophile

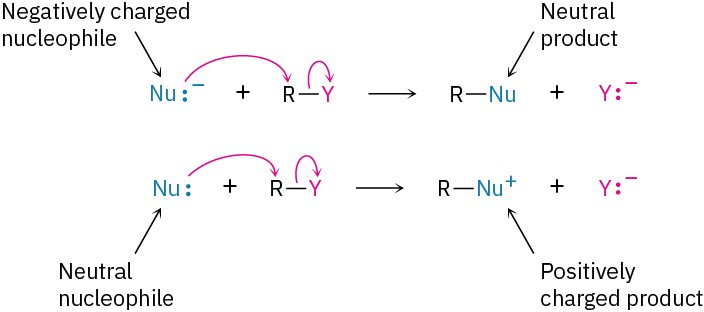

Another variable that has a major effect on the SN2 reaction is the nature of the nucleophile. Any species, either neutral or negatively charged, can act as a nucleophile as long as it has an unshared pair of electrons; that is, as long as it is a Lewis base. If the nucleophile is negatively charged, the product is neutral; if the nucleophile is neutral, the product is positively charged.

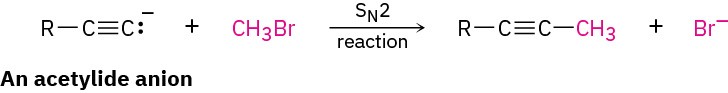

A wide array of substances can be prepared using nucleophilic substitution reactions. In fact, we’ve already seen examples in previous chapters. For instance, the reaction of an acetylide anion with an alkyl halide, discussed in Section 9.8, is an SN2 reaction in which the acetylide nucleophile displaces a halide leaving group.

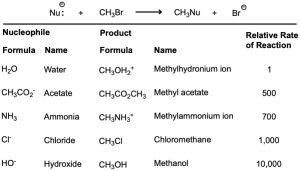

Table 11.1 lists some nucleophiles in the order of their reactivity, shows the products of their reactions with bromomethane, and gives the relative rates of their reactions. There are large differences in the rates at which various nucleophiles react.

Table 11.1 Some SN2 Reactions with Bromomethane

What are the reasons for the reactivity differences observed in Table 11.1? Why do some reactants appear to be much more “nucleophilic” than others? The answers to these questions aren’t straightforward. Part of the problem is that the term nucleophilicity is imprecise. The term is usually taken to be a measure of the affinity of a nucleophile for a carbon atom in the SN2 reaction, but the reactivity of a given nucleophile can change from one reaction to the next. The exact nucleophilicity of a species in a given reaction depends on the substrate, the solvent, and even the reactant concentrations. Detailed explanations for the observed nucleophilicities aren’t always simple, but some trends can be detected from the data of Table 11.1.

- Nucleophilicity roughly parallels basicity when comparing nucleophiles that have the same reacting atom. Thus, OH– is both more basic and more nucleophilic than acetate ion, CH3CO2–, which in turn is more basic and more nucleophilic than H2O. Since “nucleophilicity” is usually taken as the affinity of a Lewis base for a carbon atom in the SN2 reaction and “basicity” is the affinity of a base for a proton, it’s easy to see why there might be a correlation between the two kinds of behavior.

- Nucleophilicity usually increases going down a column of the periodic table. Thus, HS– is more nucleophilic than HO–, and the halide reactivity order is I– > Br– > Cl–. Going down the periodic table, elements have their valence electrons in successively larger shells where they are successively farther from the nucleus, less tightly held, and consequently more reactive. This matter is complex, though, and the nucleophilicity order can change depending on the solvent.

- Negatively charged nucleophiles are usually more reactive than neutral ones. As a result, SN2 reactions are often carried out under basic conditions rather than neutral or acidic conditions.

Problem 11-4

What product would you expect from SN2 reaction of 1-bromobutane with each of the following?

(a) NaI

(b) KOH

(c) H−C≡C−Li

(d) NH3

Problem 11-5

Which substance in each of the following pairs is more reactive as a nucleophile? Explain.

(a) (CH3)2N– or (CH3)2NH

(b) (CH3)3B or (CH3)3N

(c) H2O or H2S

The Leaving Group

Still another variable that can affect the SN2 reaction is the nature of the group displaced by the incoming nucleophile, the leaving group. Because the leaving group is expelled with a negative charge in most SN2 reactions, the best leaving groups are those that best stabilize the negative charge in the transition state. The greater the extent of charge stabilization by the leaving group, the lower the energy of the transition state and the more rapid the reaction. But as we saw in Section 2.8, the groups that best stabilize a negative charge are also the weakest bases. Thus, weak bases such as Cl–, Br–, and tosylate ion make good leaving groups, while strong bases such as OH– and NH2– make poor leaving groups.

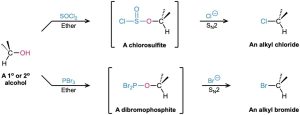

It’s just as important to know which are poor leaving groups as to know which are good, and the preceding data clearly indicate that F–, HO–, RO–, and H2N– are not displaced by nucleophiles. In other words, alkyl fluorides, alcohols, ethers, and amines do not typically undergo SN2 reactions. To carry out an SN2 reaction with an alcohol, it’s necessary to convert the alcohol into a better leaving group. This, in fact, is just what happens when a primary or secondary alcohol is converted into either an alkyl chloride by reaction with SOCl2 or an alkyl bromide by reaction with PBr3 (Section 10.5). Note that an inversion of stereochemical configuration takes place in these reactions.

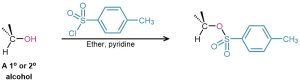

Alternatively, an alcohol can be made more reactive toward nucleophilic substitution by treating it with para-toluenesulfonyl chloride to form a tosylate. As noted previously, tosylates are even more reactive than halides in nucleophilic substitutions. Note that tosylate formation does not change the configuration of the oxygen-bearing carbon because the C–O bond is not broken.

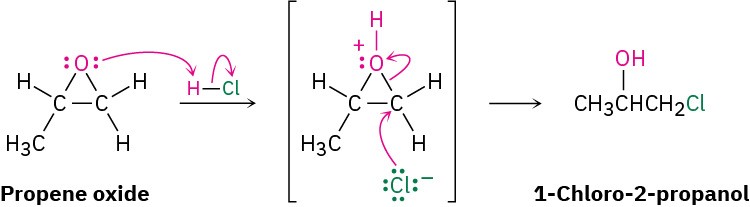

The one general exception to the rule that ethers don’t typically undergo SN2 reactions pertains to epoxides, the three-membered cyclic ethers that we saw in Section 8.7. Because of the angle strain in their three-membered ring, epoxides are much more reactive than other ethers. They react with aqueous acid to give 1,2-diols, as we saw in Section 8.7, and they react readily with many other nucleophiles as well. Propene oxide, for instance, reacts with HCl to give 1-chloro-2-propanol by an SN2 backside attack on the less hindered primary carbon atom. We’ll look at the process in more detail in Section 18.5.

Problem 11-6

Rank the following compounds in order of their expected reactivity toward SN2 reaction: CH3Br, CH3OTs, (CH3)3CCl, (CH3)2CHCl

The Solvent

The rates of SN2 reactions are strongly affected by the solvent. Protic solvents—those that contain an –OH or –NH group—are generally the worst for SN2 reactions, while polar aprotic solvents, which are polar but don’t have an –OH or –NH group, are the best.

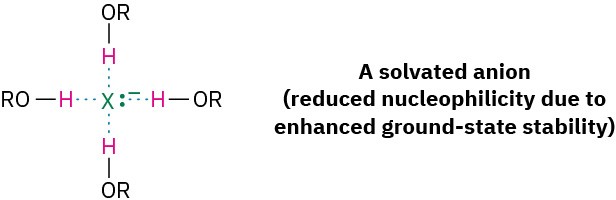

Protic solvents, such as methanol and ethanol, slow down SN2 reactions by solvation of the reactant nucleophile. The solvent molecules hydrogen-bond to the nucleophile and form a cage around it, thereby lowering its energy and reactivity.

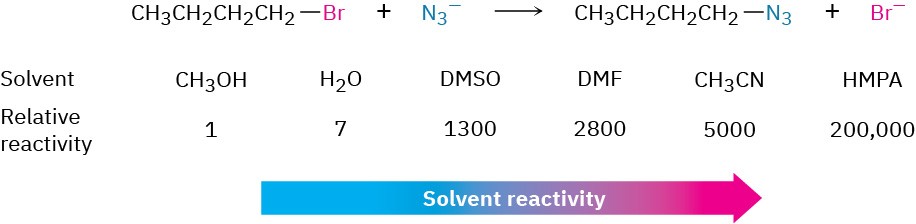

In contrast with protic solvents—which decrease the rates of SN2 reactions by lowering the ground-state energy of the nucleophile—polar aprotic solvents increase the rates of SN2 reactions by raising the ground-state energy of the nucleophile. Acetonitrile (CH3CN), dimethylformamide [(CH3)2NCHO, abbreviated DMF], and dimethyl sulfoxide [(CH3)2SO, abbreviated DMSO] are particularly useful. A solvent known as hexamethylphosphoramide [(CH3)2N]3PO, abbreviated HMPA] can also be useful but it should only be handled with great care and not be allowed to touch the eyes or skin. These solvents can dissolve many salts because of their high polarity, but they tend to solvate metal cations rather than nucleophilic anions. As a result, the bare, unsolvated anions have a greater nucleophilicity and SN2 reactions take place at correspondingly increased rates. For instance, a rate increase of 200,000 has been observed on changing from methanol to HMPA for the reaction of azide ion with 1-bromobutane.

Problem 11-7

Organic solvents like benzene, ether, and chloroform are neither protic nor strongly polar. What effect would you expect these solvents to have on the reactivity of a nucleophile in SN2 reactions?

A Summary of SN2 Reaction Characteristics

The effects on SN2 reactions of the four variables—substrate structure, nucleophile, leaving group, and solvent—are summarized in the following statements and in the energy diagrams of Figure 11.8:

Figure 11.8 Energy diagrams showing the effects of (a) substrate, (b) nucleophile, (c) leaving group, and (d) solvent on SN2 reaction rates. Substrate and leaving group effects are felt primarily in the transition state. Nucleophile and solvent effects are felt primarily in the reactant ground state.