A scientific revolution is now under way in molecular biology, as scientists learn how to manipulate and harness the genetic machinery of organisms. None of the extraordinary advances of the past several decades would have been possible, however, were it not for the discovery in 1977 of methods for sequencing immense DNA chains.

The first step in DNA sequencing is to cleave the enormous chain at known points to produce smaller, more manageable pieces, a task accomplished by the use of restriction endonucleases, or restriction enzymes. Each different restriction enzyme, of which more than 4000 are known and approximately 600 are commercially available, cleaves a DNA molecule at a point in the chain where a specific base sequence occurs. For example, the restriction enzyme AluI cleaves between G and C in the four-base sequence AG-CT. Note that the sequence is a palindrome, meaning that the sequence (5′)-AGCT-(3′) is the same as its complement (3′)-TCGA-(5′) when both are read in the same 5′ → 3′ direction. The same is true for other restriction endonucleases.

If the original DNA molecule is cut with another restriction enzyme having a different specificity for cleavage, still other segments are produced whose sequences partially overlap those produced by the first enzyme. Sequencing all the segments, followed by identification of the overlapping regions, allows for complete DNA sequencing.

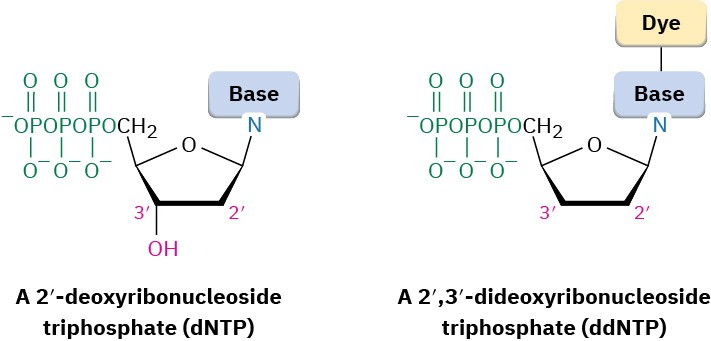

A dozen or so different methods of DNA sequencing are now available, and many others are under development. The Sanger dideoxy method is among the most frequently used and was the method responsible for first sequencing the entire human genome of 3.0 billion base pairs. In commercial sequencing instruments, the dideoxy method begins with a mixture of the following:

- The restriction fragment to be sequenced

- A small piece of DNA called a primer, whose sequence is complementary to that on the 3′ end of the restriction fragment

- The four 2′-deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs)

- Very small amounts of the four 2′,3′-dideoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (ddNTPs), each of which is labeled with a fluorescent dye of a different color (A 2′,3′-dideoxyribonucleoside triphosphate is one in which both 2′ and 3′ –OH groups are missing from ribose.)

DNA polymerase is added to the mixture, and a strand of DNA complementary to the restriction fragment begins to grow from the end of the primer. Most of the time, only normal deoxyribonucleotides are incorporated into the growing chain because of their much higher concentration in the mixture, but every so often, a dideoxyribonucleotide is incorporated. When that happens, DNA synthesis stops because the chain end no longer has a 3′-hydroxyl group for adding further nucleotides.

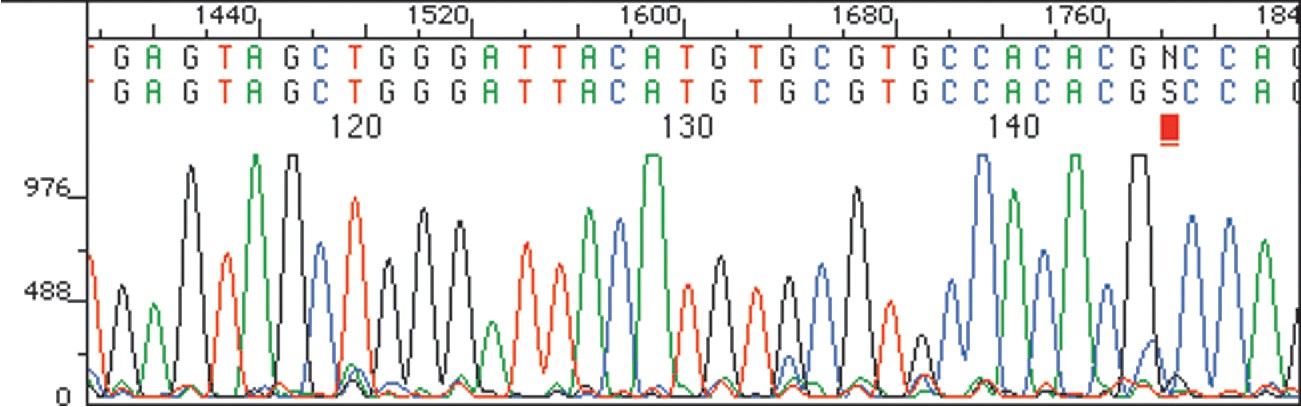

When reaction is complete, the product consists of a mixture of DNA fragments of all possible lengths, each terminated by one of the four dye-labeled dideoxyribonucleotides. This product mixture is then separated according to the size of the pieces by gel electrophoresis (Section 26.2), and the identity of the terminal dideoxyribonucleotide in each piece—and thus the sequence of the restriction fragment—is determined by noting the color with which the attached dye fluoresces. Figure 28.9 shows a typical result.

Figure 28.9The sequence of a restriction fragment determined by the Sanger dideoxy method can be read simply by noting the colors of the dye attached to each of the various terminal nucleotides.

So efficient is the automated dideoxy method that sequences up to 1100 nucleotides in length, with a throughput of up to 19,000 bases per hour, can be sequenced with 98% accuracy. After a decade of work and a cost of about $500 million, preliminary sequence information for the entire human genome of 3.0 billion base pairs was announced early in 2001 and complete information was released in 2003. More recently, the genome sequencing of individuals, including that of James Watson, one of the discoverers of the double helix, has been accomplished. The sequencing price per genome is dropping rapidly

and is currently less than $1,000, meaning that the routine sequencing of individuals is within reach.

Remarkably, our genome appears to contain only about 21,000 genes, less than one-fourth the previously predicted number and only about twice the number found in the common roundworm. It’s also interesting to note that the number of genes in a human (21,000) is much smaller than the number of kinds of proteins (perhaps 500,000). This discrepancy arises because most proteins are modified in various ways after translation (posttranslational modifications), so a single gene can ultimately give many different proteins.