As each functional group is discussed in future chapters, mass-spectral fragmentations characteristic of that group will be described. As a preview, though, we’ll point out some distinguishing features of several common functional groups.

Alcohols

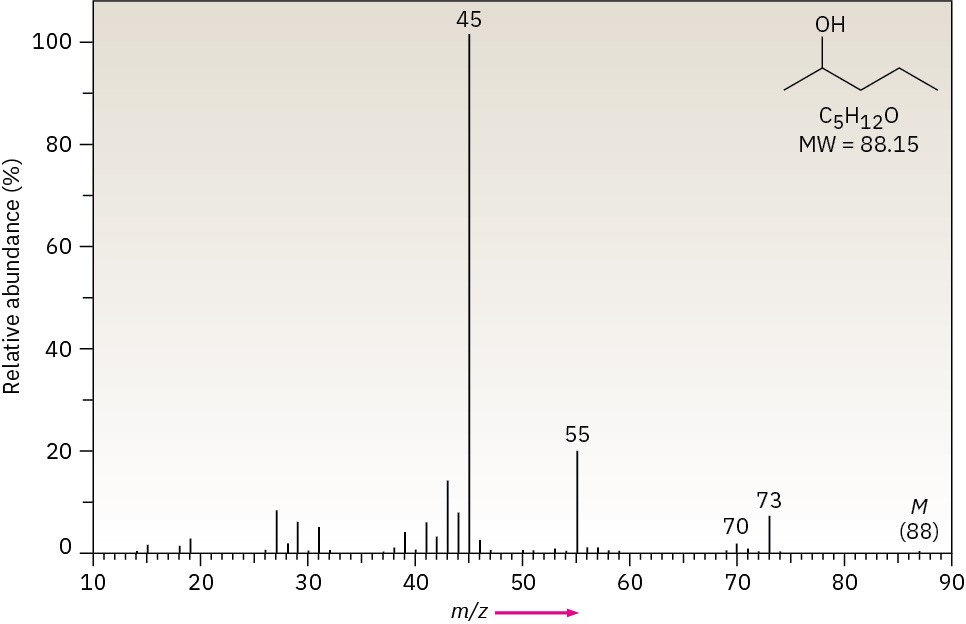

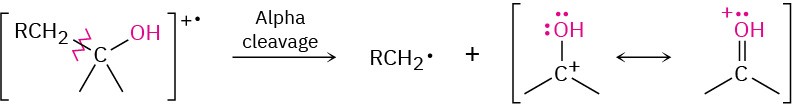

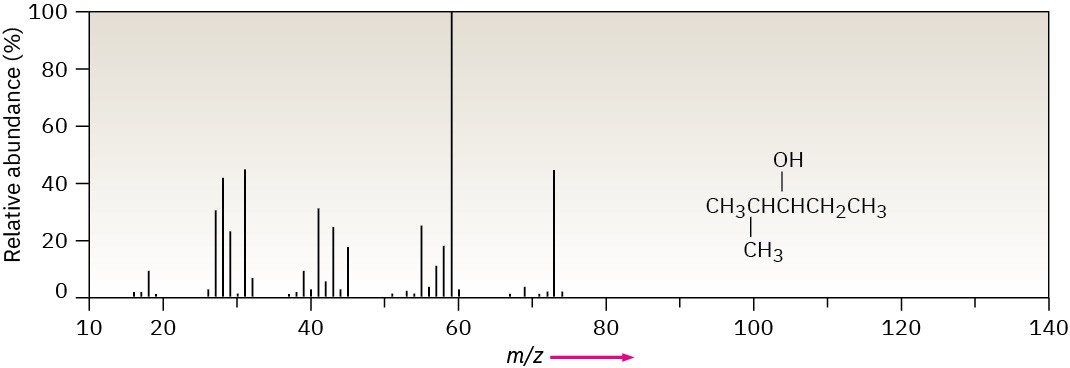

Alcohols undergo fragmentation in a mass spectrometer by two pathways: alpha cleavage and dehydration. In the α-cleavage pathway, a C–C bond nearest the hydroxyl group is broken, yielding a neutral radical plus a resonance-stabilized, oxygen-containing cation. This type of fragmentation is seen in the spectrum of 2-pentanol in Figure 12.10.

Figure 12.10Mass spectrum of 2-pentanol.

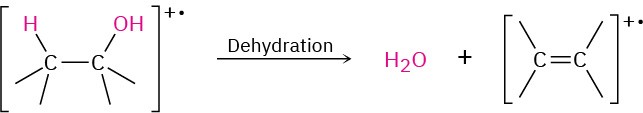

In the dehydration pathway, water is eliminated, yielding an alkene radical cation with a mass 18 amu less than M+. For simplicity, we have drawn the dehydration below as an E2- type process. Often the hydrogen that is lost is not beta to the hydroxyl. Only a small peak from dehydration is observed in the spectrum of 2-pentanol (Figure 12.10).

Amines

The nitrogen rule of mass spectrometry says that a compound with an odd number of nitrogen atoms has an odd-numbered molecular weight. The logic behind the rule comes from the fact that nitrogen is trivalent, thus requiring an odd number of hydrogen atoms. The presence of nitrogen in a molecule is often detected simply by observing its mass spectrum. An odd-numbered molecular ion usually means that the unknown compound has one or three nitrogen atoms, and an even-numbered molecular ion usually means that a compound has either zero or two nitrogen atoms.

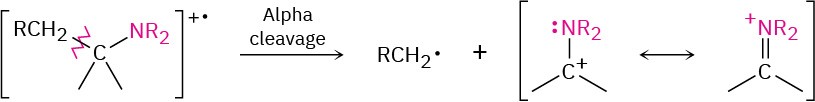

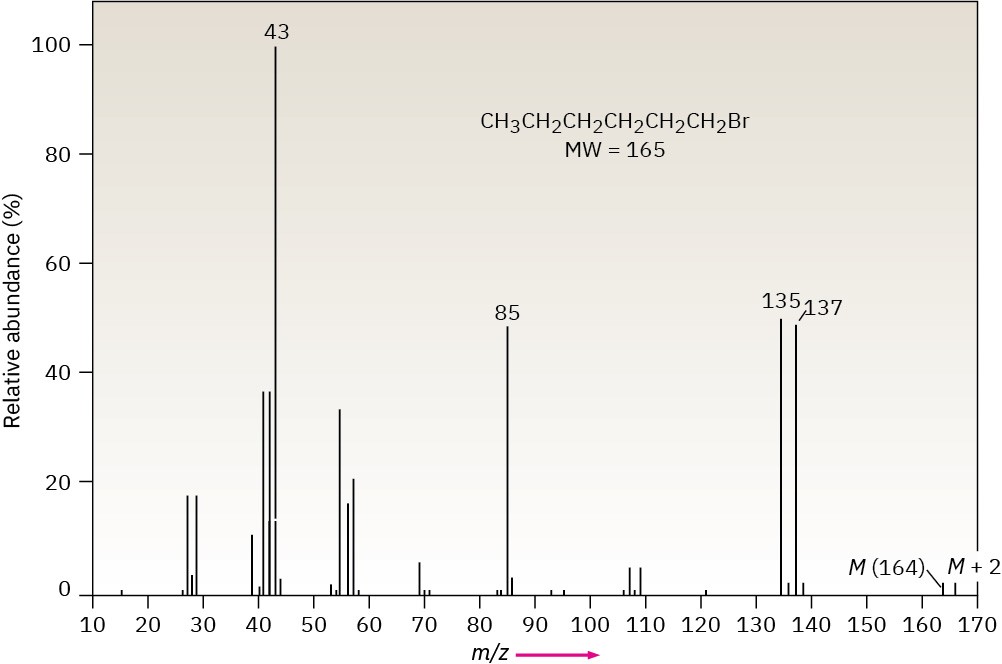

Aliphatic amines undergo a characteristic α cleavage in a mass spectrometer, similar to that observed for alcohols. A C–C bond nearest the nitrogen atom is broken, yielding an alkyl radical and a resonance-stabilized, nitrogen-containing cation.

The mass spectrum of triethylamine has a base peak at m/z = 86, which arises from an alpha cleavage resulting in the loss of a methyl group (Figure 12.11).

Figure 12.11Mass spectrum of triethylamine.

Halides

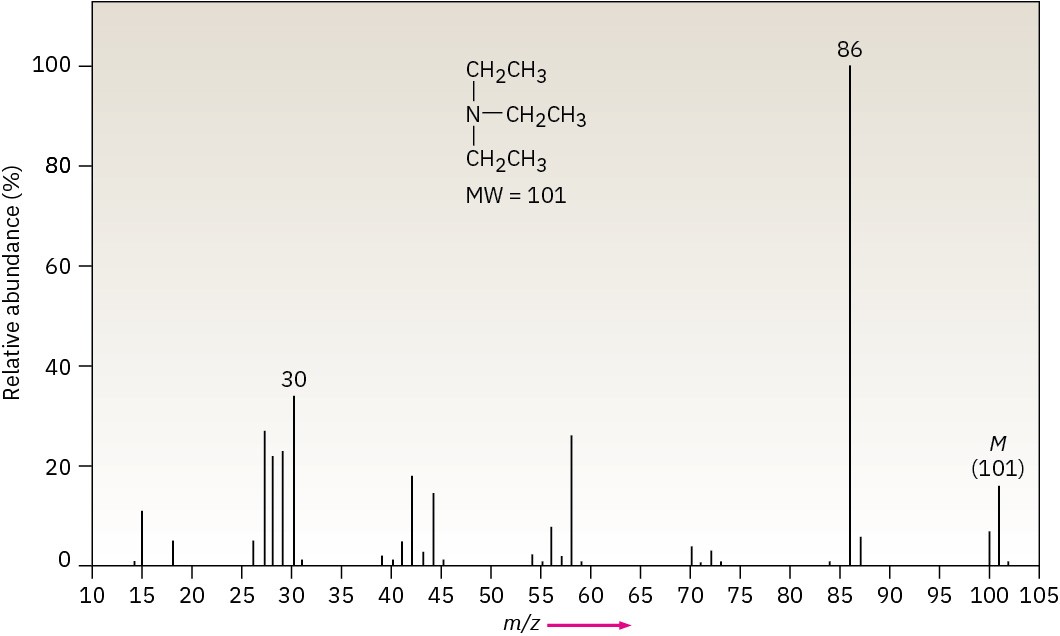

The fact that some elements have two common isotopes gives their mass spectra a distinctive appearance. Chlorine, for example, exists as two isotopes, 35Cl and 37Cl, in roughly a 3:1 ratio. In a sample of chloroethane, three out of four molecules contain a 35Cl atom and one out of four has a 37Cl atom. In the mass spectrum of chloroethane (Figure 12.12 we see the molecular ion (M) at m/z = 64 for ions that contain a 35Cl and another peak at m/z = 66, called the M + 2 peak, for ions containing a 37Cl. The ratio of the relative abundance of M : M + 2 is about 3:1, a reflection of the isotopic abundances of chlorine.

Figure 12.12 Mass spectrum of chloroethane.

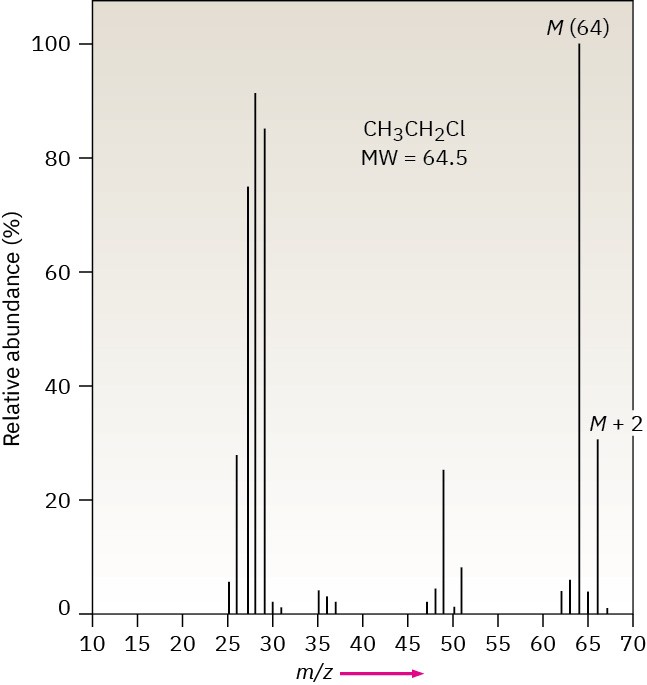

In the case of bromine, the isotopic distribution is 50.7% 79Br and 49.3% 81Br. In the mass spectrum of 1-bromohexane (Figure 12.13) the molecular ion appears at m/z = 164 for 79Br-containing ions and the M + 2 peak is at m/z = 166 for 81Br-containing ions. The ions at m/z = 135 and 137 are informative as well. The two nearly equally large peaks tell us that the ions at those m/z values still contain the bromine atom. The peak at m/z = 85, on the other hand, does not contain bromine because there is not a large peak at m/z = 87.

Figure 12.13 Mass spectrum of 1-bromohexane.

Carbonyl Compounds

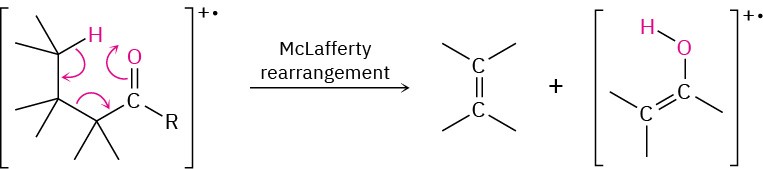

Ketones and aldehydes that have a hydrogen on a carbon three atoms away from the carbonyl group undergo a characteristic mass-spectral cleavage called the McLafferty rearrangement. The hydrogen atom is transferred to the carbonyl oxygen, a C–C bond between the alpha and beta carbons is broken, and a neutral alkene fragment is produced. The charge remains with the oxygen-containing fragment.

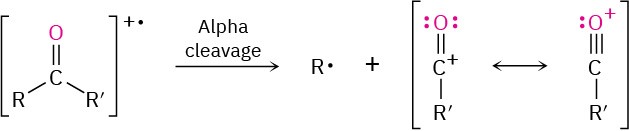

In addition, ketones and aldehydes frequently undergo α cleavage of the bond between the carbonyl carbon and the neighboring carbon to yield a neutral radical and a resonance- stabilized acyl cation. Because the carbon neighboring the carbonyl carbon is called the alpha carbon, the reaction is called an alpha cleavage.

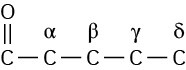

(To be more general about neighboring positions in carbonyl compounds, Greek letters are used in alphabetical order: alpha, beta, gamma, delta, and so on.)

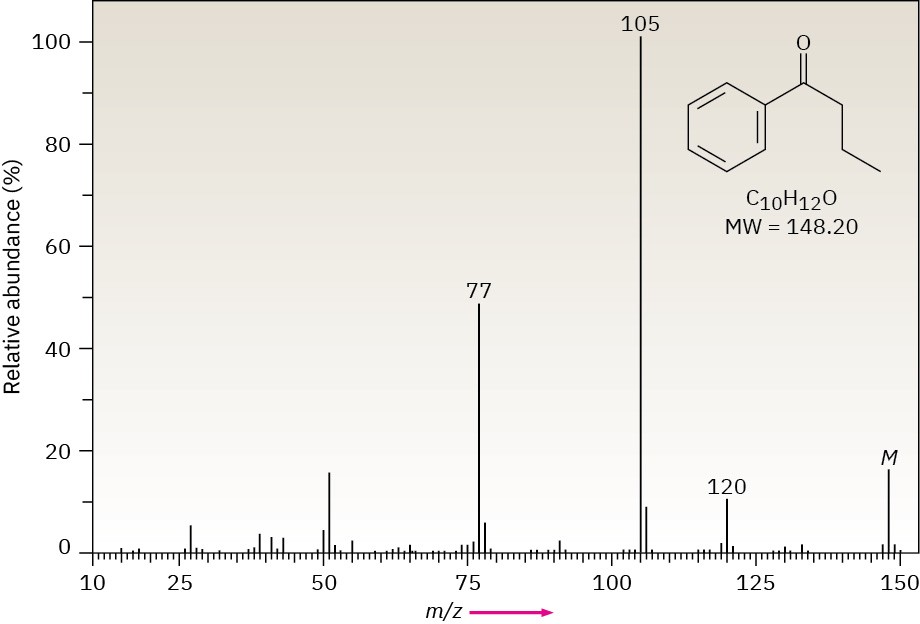

The mass spectrum of butyrophenone illustrates both alpha cleavage and the McLafferty rearrangement (Figure 12.14). Alpha cleavage of the propyl substituent results in the loss of C3H7 = 43 mass units from the parent ion at m/z = 148 to give the fragment ion at m/z = 105. A McLafferty rearrangement of butyrophenone results in the loss of ethylene, C2H4 = 28 mass units, from the parent leaving the ion at m/z = 120.

Figure 12.14 Mass spectrum of butyrophenone.

Worked Example 12.2 Identifying Fragmentation Patterns in a Mass Spectrum

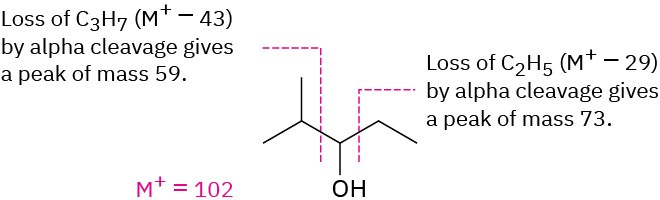

The mass spectrum of 2-methyl-3-pentanol is shown in Figure 12.15. What fragments can you identify?

Figure 12.15 Mass spectrum of 2-methyl-3-pentanol, for Worked Example 12.2.

Strategy – Calculate the mass of the molecular ion, and identify the functional groups in the molecule. Then write the fragmentation processes you might expect, and compare the masses of the resultant fragments with the peaks present in the spectrum.

Solution – 2-methyl-3-pentanol, an open-chain alcohol, has M+ = 102 and might be expected to fragment by α cleavage and by dehydration. These processes would lead to fragment ions of m/z = 84, 73, and 59. Of the three expected fragments, dehydration is not observed (no m/z = 84 peak), but both α cleavages take place (m/z = 73, 59).

Problem 12-3

What are the masses of the charged fragments produced in the following cleavage pathways?

(a) alpha cleavage of 2-pentanone, CH3COCH2CH2CH3

(b) dehydration of cyclohexanol

(c) McLafferty rearrangement of 4-methyl-2-pentanone, CH3COCH2CH(CH3)2

(d) alpha cleavage of triethylamine, (CH3CH2)3N

Problem 12-4

List the masses of the parent ion and of several fragments you might expect to find in the mass spectrum of the following molecule: