The study of chirality originated in the early 19th century during investigations into the nature of plane-polarized light. A beam of ordinary light consists of electromagnetic waves that oscillate in an infinite number of planes at right angles to its direction of travel. When a beam of ordinary light passes through a device called a polarizer, however, only the light waves oscillating in a single plane pass through and the light is said to be plane-polarized. Light waves in all other planes are blocked out.

The remarkable observation was made that when a beam of plane-polarized light passes through a solution of certain organic molecules, such as sugar or camphor, the plane of polarization is rotated through an angle, α. Not all organic substances exhibit this property, but those that do are said to be optically active.

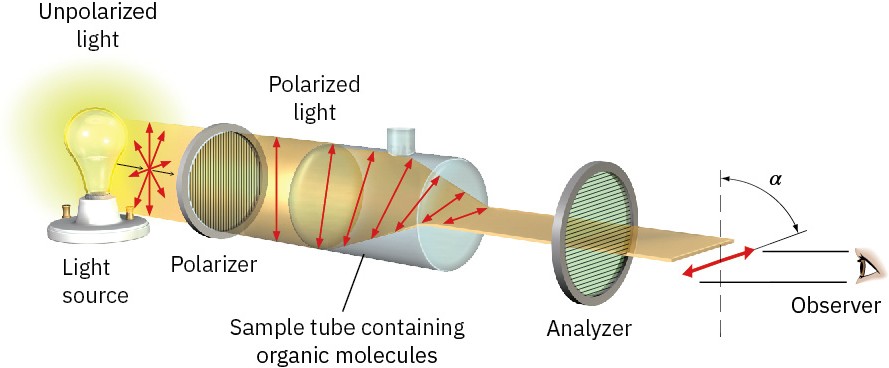

The angle of rotation can be measured with an instrument called a polarimeter, represented in Figure 5.6. A solution of optically active organic molecules is placed in a sample tube, plane-polarized light is passed through the tube, and rotation of the polarization plane occurs. The light then goes through a second polarizer called the analyzer. By rotating the analyzer until the light passes through it, we can find the new plane of polarization and can tell to what extent rotation has occurred.

Figure 5.6 Schematic representation of a polarimeter. Plane-polarized light passes through a solution of optically active molecules, which rotate the plane of polarization.

In addition to determining the extent of rotation, we can also find the direction. From the vantage point of the observer looking directly at the analyzer, some optically active molecules rotate polarized light to the left (counterclockwise) and are said to be levorotatory, whereas others rotate polarized light to the right (clockwise) and are said to be dextrorotatory. By convention, rotation to the left is given a minus sign (−) and rotation to the right is given a plus sign (+). (−)-Morphine, for example, is levorotatory, and (+)- sucrose is dextrorotatory.

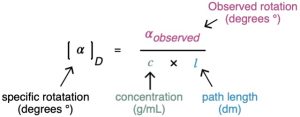

The extent of rotation observed in a polarimetry experiment depends on the number of optically active molecules encountered by the light beam. This number, in turn, depends on sample concentration and sample pathlength. If the concentration of the sample is doubled, the observed rotation doubles. If the concentration is kept constant but the length of the sample tube is doubled, the observed rotation doubles. It also happens that the angle of rotation depends on the wavelength of the light used.

To express optical rotations in a meaningful way so that comparisons can be made, we have to choose standard conditions. The specific rotation, [α]D, of a compound is defined as the observed rotation when light of 589.6 nanometer (nm; 1 nm = 10−9 m) wavelength is used with a sample pathlength l of 1 decimeter (dm; 1 dm = 10 cm) and a sample concentration c of 1 g/cm3. Light of 589.6 nm, the so-called sodium D line, is the yellow light emitted from common sodium street lamps.

When optical rotations are expressed in this standard way, the specific rotation, [α]D, is a physical constant characteristic of a given optically active compound. For example, (+)- lactic acid has [α]D = +3.82, and (−)-lactic acid has [α]D = −3.82. That is, the two enantiomers rotate plane-polarized light to exactly the same extent but in opposite directions. Note that the units of specific rotation are [(deg · cm2)/g] but the values are usually expressed without units.