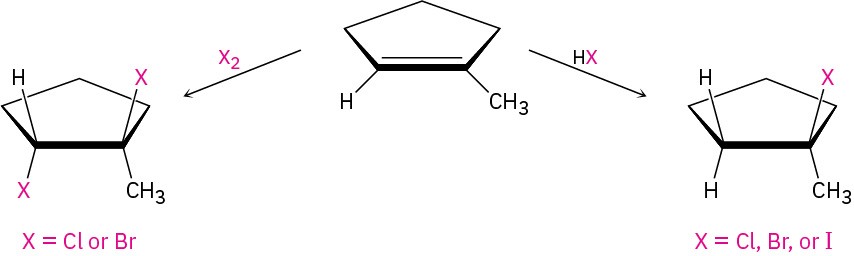

We’ve already seen several methods for preparing alkyl halides from alkenes, including the reactions of HX and X2 with alkenes in electrophilic addition reactions (Section 7.7 and Section 8.2). The hydrogen halides HCl, HBr, and HI react with alkenes by a polar mechanism to give the product of Markovnikov addition. Bromine and chlorine undergo anti addition through halonium ion intermediates to give 1,2-dihalogenated products.

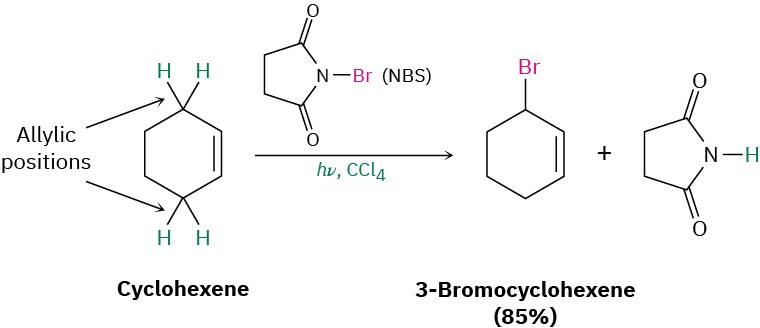

Another laboratory method for preparing alkyl halides from alkenes is by reaction with N– bromosuccinimide (abbreviated NBS), in the presence of ultraviolet light, to give products resulting from substitution of hydrogen by bromine at the position next to the double bond—the allylic position. Cyclohexene, for example, gives 3-bromocyclohexene.

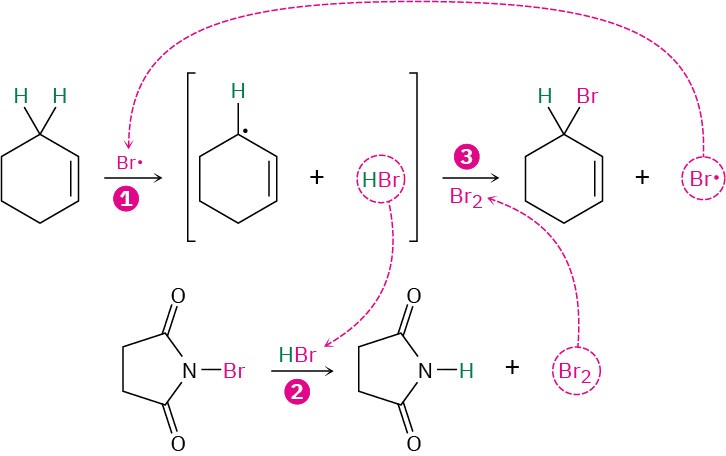

This allylic bromination with NBS is analogous to the alkane chlorination reaction discussed in the previous section and occurs by a radical chain-reaction pathway (Figure 10.3). As in alkane halogenation, a Br· radical abstracts an allylic hydrogen atom, forming an allylic radical plus HBr. The HBr then reacts with NBS to form Br2, which in turn reacts with the allylic radical to yield the brominated product and a Br· radical that cycles back into the first step and carries on the chain.

Figure 10.3 Mechanism of allylic bromination of an alkene with NBS. The process is a radical chain reaction in which (1) a Br· radical abstracts an allylic hydrogen atom of the alkene and gives an allylic radical plus HBr. (2) The HBr then reacts with NBS to form Br2, which (3) reacts with the allylic radical to yield the bromoalkene product and a Br· radical that continues the chain.

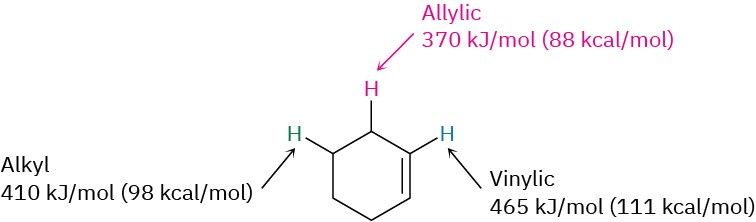

Why does bromination with NBS occur exclusively at an allylic position rather than elsewhere in the molecule? The answer, once again, is found by looking at bond dissociation energies to see the relative stabilities of various kinds of radicals. Although a typical secondary alkyl C−H bond has a strength of about 410 kJ/mol and a typical vinylic C−H bond has a strength of 465 kJ/mol, an allylic C−H bond has a strength of only about 370 kJ/mol. An allylic radical is therefore more stable than a typical alkyl radical with the same substitution by about 40 kJ/mol.

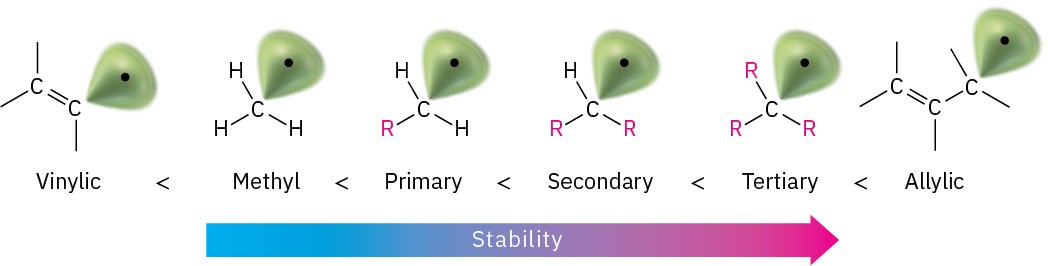

We can thus expand the stability ordering to include vinylic and allylic radicals.