The direct nucleophilic acyl substitution of a carboxylic acid is difficult because –OH is a poor leaving group (Section 11.3). Thus, it’s usually necessary to enhance the reactivity of the acid, either by using a strong acid catalyst to protonate the carboxyl and make it a better acceptor or by converting the –OH into a better leaving group. Under the right circumstances, however, acid chlorides, anhydrides, esters, and amides can all be prepared from carboxylic acids by nucleophilic acyl substitution reactions.

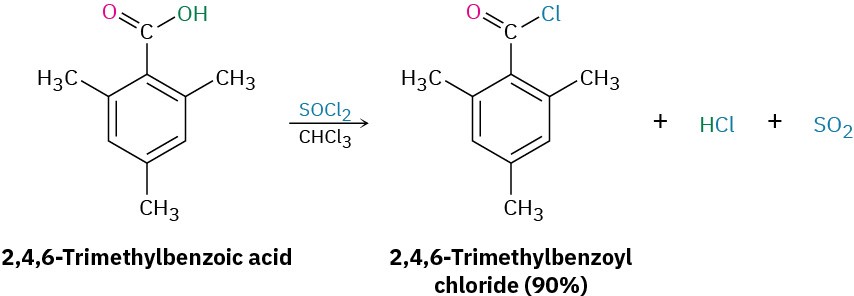

Conversion of Carboxylic Acids into Acid Chlorides

In the laboratory, carboxylic acids are converted into acid chlorides by treatment with thionyl chloride, SOCl2.

This reaction occurs by a nucleophilic acyl substitution pathway in which the carboxylic acid is first converted into an acyl chlorosulfite intermediate, thereby replacing the –OH of the acid with a much better leaving group. The chlorosulfite then reacts with a nucleophilic chloride ion. You might recall from Section 17.6 that an analogous chlorosulfite is involved in the reaction of an alcohol with SOCl2 to yield an alkyl chloride.

This reaction occurs by a nucleophilic acyl substitution pathway in which the carboxylic acid is first converted into an acyl chlorosulfite intermediate, thereby replacing the –OH of the acid with a much better leaving group. The chlorosulfite then reacts with a nucleophilic chloride ion. You might recall from Section 17.6 that an analogous chlorosulfite is involved in the reaction of an alcohol with SOCl2 to yield an alkyl chloride.

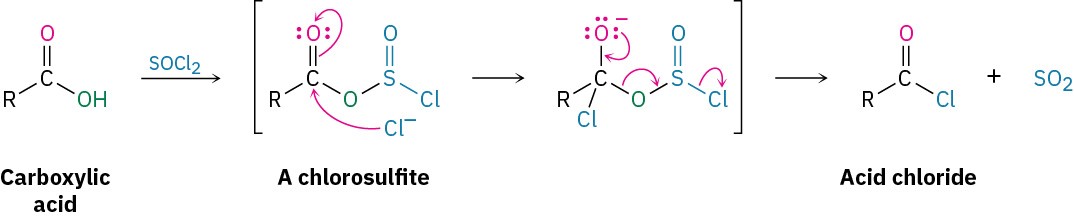

Conversion of Carboxylic Acids into Acid Anhydrides

Acid anhydrides can be derived from two molecules of carboxylic acid by heating to remove 1 equivalent of water. Because of the high temperatures needed, however, only acetic anhydride is commonly prepared this way.

Conversion of Carboxylic Acids into Esters

Perhaps the most useful reaction of carboxylic acids is their conversion into esters. There are many methods for accomplishing this, including the SN2 reaction of a carboxylate anion with a primary alkyl halide that we saw in Section 11.3.

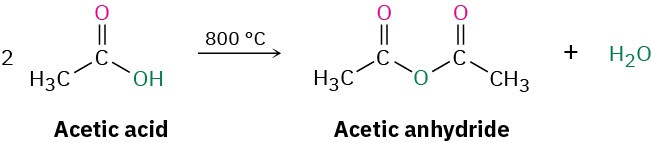

Esters can also be synthesized by an acid-catalyzed nucleophilic acyl substitution reaction of a carboxylic acid with an alcohol, a process called the Fischer esterification reaction.

Unfortunately, the need for an excess of a liquid alcohol as solvent effectively limits the method to the synthesis of methyl, ethyl, propyl, and butyl esters.

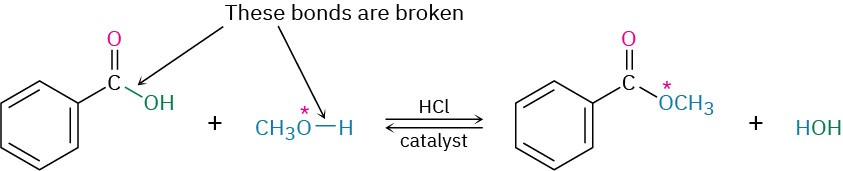

The mechanism of the Fischer esterification reaction is shown in Figure 21.5. Carboxylic acids are not reactive enough to undergo nucleophilic addition directly, but their reactivity is greatly enhanced in the presence of a strong acid such as HCl or H2SO4. The mineral acid protonates the carbonyl-group oxygen atom, thereby giving the carboxylic acid a positive charge and rendering it much more reactive toward nucleophiles. Subsequent loss of water from the tetrahedral intermediate yields the ester product.

Figure 21.5 Mechanism of Fischer esterification. The reaction is an acid-catalyzed, nucleophilic acyl substitution of a carboxylic acid.

The net effect of Fischer esterification is substitution of an –OH group by –OR′. All steps are reversible, and the reaction typically has an equilibrium constant close to 1. Thus, the reaction can be driven in either direction by the choice of reaction conditions. Ester formation is favored when a large excess of alcohol is used as solvent, but carboxylic acid formation is favored when a large excess of water is present.

Evidence in support of the mechanism shown in Figure 21.5 comes from isotope-labeling experiments. When 18O-labeled methanol reacts with benzoic acid, the methyl benzoate produced is found to be 18O-labeled whereas the water produced is unlabeled. Thus, it is the C–OH bond of the carboxylic acid that is broken during the reaction rather than the CO– H bond and the RO–H bond of the alcohol that is broken rather than the R–OH bond.

Worked Example 21.2 Synthesizing an Ester from an Acid

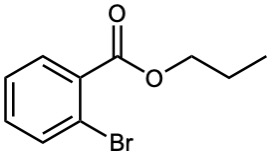

How might you prepare the following ester using a Fischer esterification reaction?

Strategy

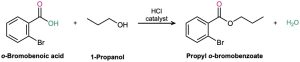

Begin by identifying the two parts of the ester. The acyl part comes from the carboxylic acid and the –OR part comes from the alcohol. In this case, the target molecule is propyl o-bromobenzoate, so it can be prepared by treating o-bromobenzoic acid with 1-propanol.

Solution

Problem 21-7

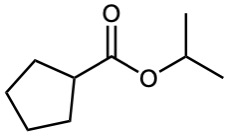

How might you prepare the following esters from the corresponding acids?

(a)

![]()

(b)

=![]()

(c)

Problem 21-8

If the following molecule is treated with acid catalyst, an intramolecular esterification reaction occurs. What is the structure of the product? (Intramolecular means within the same molecule.)

Conversion of Carboxylic Acids into Amides

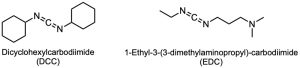

Amides are difficult to prepare by direct reaction of carboxylic acids with amines because amines are bases that convert acidic carboxyl groups into their unreactive carboxylate anions. Thus, the –OH must be replaced by a better, nonacidic leaving group to carry out a nucleophilic acyl substitution. In practice, amides are often prepared by activating the carboxylic acid with a carbodiimide (R–N═C═N–R), followed by addition of the amine.

Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropylcarbodiimide (EDC) are commonly used.

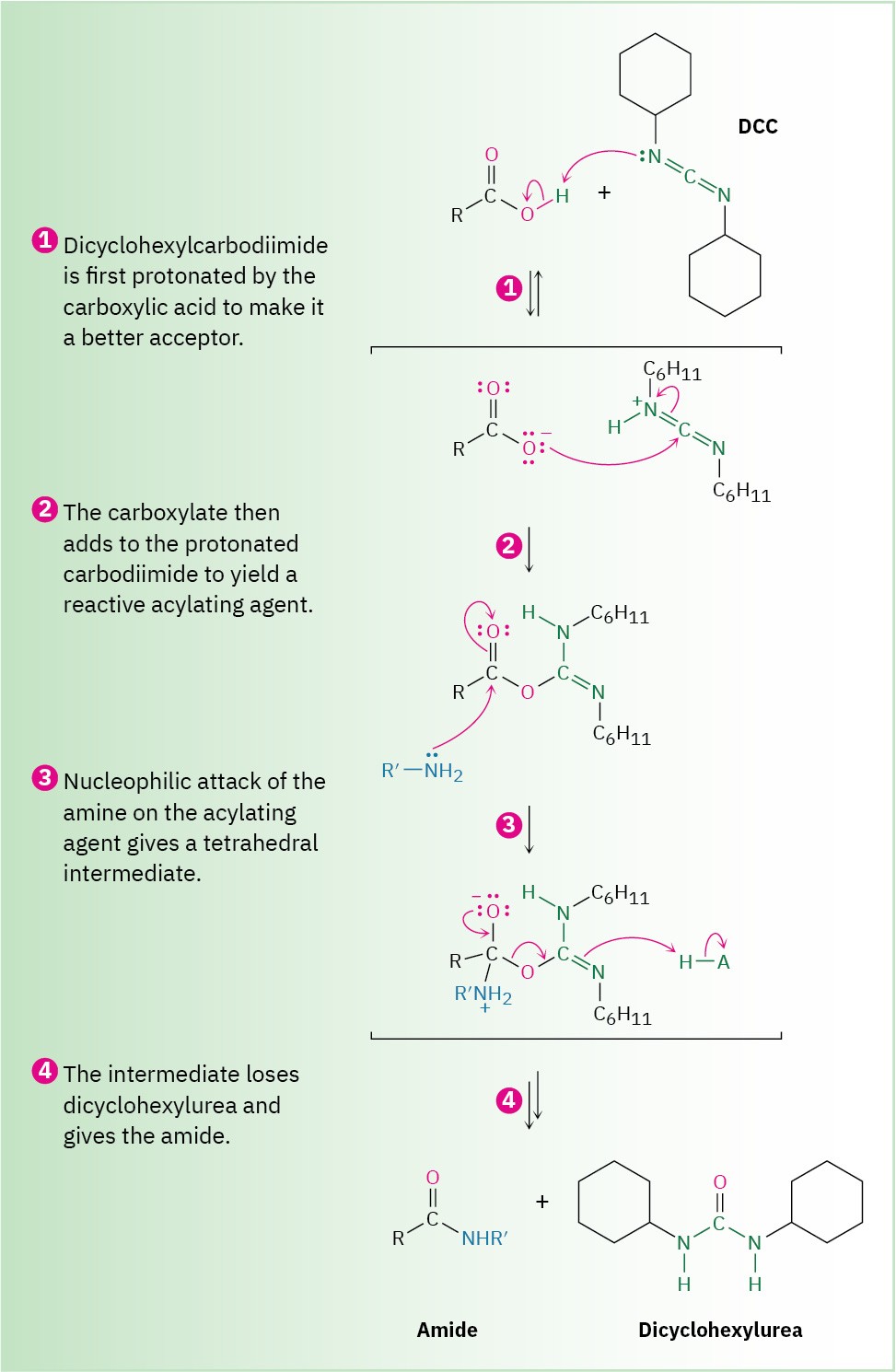

As shown in Figure 21.6, the acid first adds to a C═N double bond of DCC, and nucleophilic acyl substitution by amine then ensues. Alternatively, and depending on the reaction solvent, the reactive acyl intermediate might also react with a second equivalent of carboxylate ion to generate an acid anhydride that then reacts with the amine. The product from either pathway is the same.

Figure 21.6 Mechanism of amide formation by reaction of a carboxylic acid and an amine with dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC).

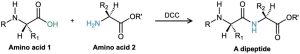

We’ll see in Section 26.7 that this carbodiimide method of amide formation is the key step in the laboratory synthesis of small proteins, or peptides. For instance, when one amino acid with its NH2 rendered unreactive and a second amino acid with its –CO2H rendered unreactive are treated with carbodiimide, a dipeptide is formed.

Conversion of Carboxylic Acids into Alcohols

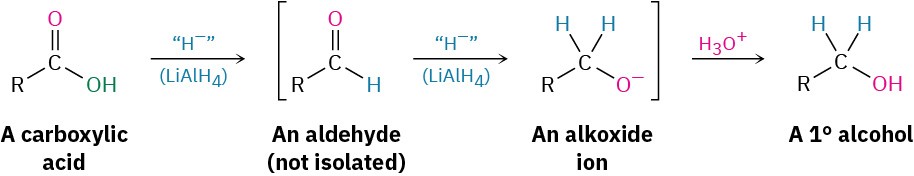

We said in Section 17.4 that carboxylic acids are reduced by LiAlH4 to give primary alcohols, but we deferred a discussion of the reaction mechanism at that time. In fact, the reduction is a nucleophilic acyl substitution reaction in which –H replaces –OH to give an aldehyde that is further reduced by nucleophilic addition to produce a primary alcohol. The aldehyde intermediate is much more reactive than the starting acid, so it reacts instantly and is not isolated.

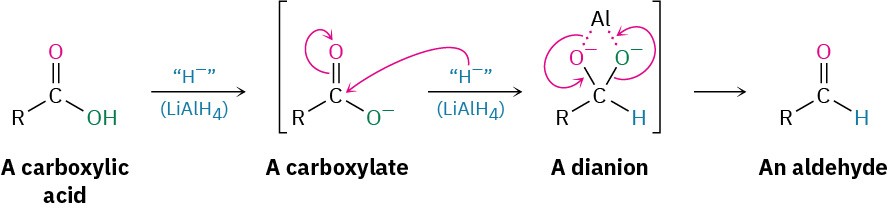

Because hydride ion is a base as well as a nucleophile, the actual nucleophilic acyl substitution step takes place on the carboxylate ion rather than on the free carboxylic acid and gives a high-energy dianion intermediate. In this intermediate, the two oxygens are complexed to a Lewis acidic aluminum species. Thus, the reaction is relatively difficult, and acid reductions require higher temperatures and extended reaction times.

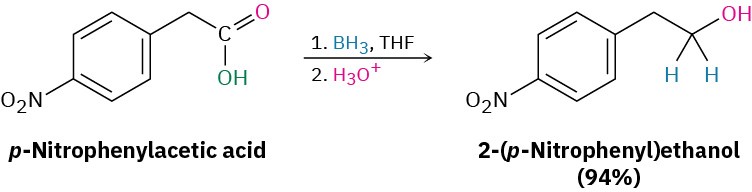

Alternatively, borane in tetrahydrofuran (BH3/THF) is a useful reagent for reducing carboxylic acids to primary alcohols. Reaction of an acid with BH3/THF occurs rapidly at room temperature, and the procedure is often preferred to reduction with LiAlH4 because of its relative ease and safety. Borane reacts with carboxylic acids faster than with any other functional group, thereby allowing selective transformations such as that on p-nitrophenylacetic acid. If the reduction of p-nitrophenylacetic acid were done with LiAlH4, both the nitro and carboxyl groups would be reduced.

Biological Conversions of Carboxylic Acids

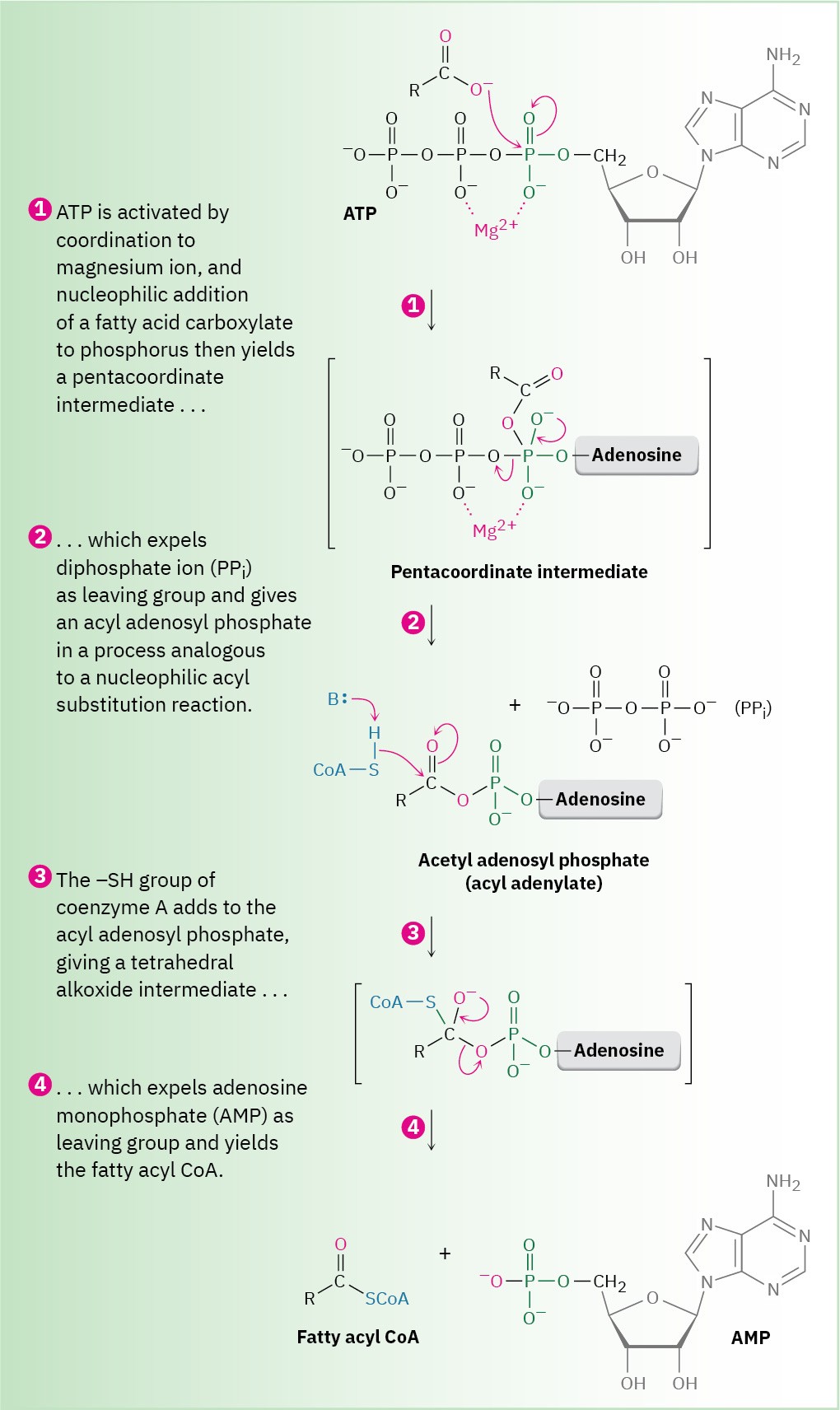

The direct conversion of a carboxylic acid to an acyl derivative by nucleophilic acyl substitution does not occur in biological chemistry. As in the laboratory, the acid must first be activated by converting the –OH into a better leaving group. This activation is often accomplished in living organisms by reaction of the acid with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to give an acyl adenosyl phosphate, or acyl adenylate, a mixed anhydride combining a carboxylic acid and adenosine monophosphate (AMP, also known as adenylic acid). In the biosynthesis of fats, for example, a long-chain carboxylic acid reacts with ATP to give an acyl adenylate, followed by subsequent nucleophilic acyl substitution of a thiol group in coenzyme A to give the corresponding acyl CoA (Figure 21.7).

Figure 21.7 In fatty-acid biosynthesis, a carboxylic acid is activated by reaction with ATP to give an acyl adenylate, which undergoes nucleophilic acyl substitution with the –SH group on coenzyme A. (ATP = adenosine triphosphate; AMP = adenosine monophosphate.)

Note that the first step in Figure 21.7—reaction of the carboxylate with ATP to give an acyl adenylate—is itself a nucleophilic acyl substitution on phosphorus. The carboxylate first adds to a P═O double bond, giving a five-coordinate phosphorus intermediate that expels diphosphate ion as a leaving group.