Figure 15.1 A fennel plant is an aromatic herb used in cooking. A phenyl group—pronounced exactly the same way—is the characteristic structural unit of “aromatic” organic compounds. (credit: modification of work “Fennel” by Ruth Hartnup/Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

The reactivity of substituted aromatic compounds, more than that of any other class of substances, is intimately tied to their exact structure. As a result, aromatic compounds provide an extraordinarily sensitive probe for studying the relationship between structure and reactivity. We’ll examine this relationship here and in the following chapter, and we’ll find that the lessons learned are applicable to all other organic compounds, including important substances such as the nucleic acids that control our genetic makeup.

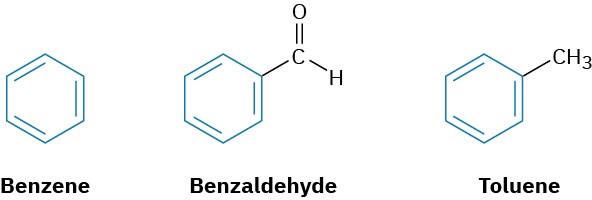

In the early days of organic chemistry, the word aromatic was used to describe such fragrant substances as benzaldehyde (from cherries, peaches, and almonds), toluene (from Tolu balsam), and benzene (from coal distillate). It was soon realized, however, that substances grouped as aromatic differed from most other organic compounds in their chemical behavior.

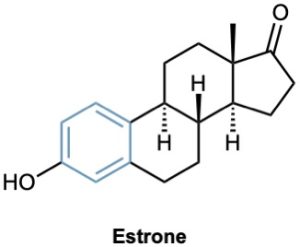

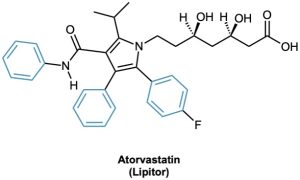

Today, the association of aromaticity with fragrance has long been lost, and we now use the word aromatic to refer to the class of compounds that contain six-membered rings with three alternating double bonds. Many naturally occurring compounds are aromatic in part, including steroids such as estrone and well-known pharmaceuticals such as the cholesterol-lowering drug atorvastatin, marketed as Lipitor. Benzene itself causes a depressed white blood cell count (leukopenia) on prolonged exposure and should not be used as a laboratory solvent.