Figure 16.1 In the 19th and early-20th centuries, benzene was used as an aftershave lotion because of its pleasant smell and as a solvent to decaffeinate coffee beans. Neither is a good idea. (credit: modification of work “Ye Old Way” by Geo. H. Walker & Co./Library of Congress)

This chapter continues the coverage of aromatic molecules begun in the preceding chapter, but we’ll shift focus to concentrate on reactions, looking at the relationship between aromatic structure and reactivity. This relationship is critical in understanding how many

biological molecules and pharmaceutical agents are synthesized and why they behave as they do.

In the preceding chapter, we looked at aromaticity—the stability associated with benzene and related compounds that contain a cyclic conjugated system of 4n + 2 π electrons. In this chapter, we’ll look at some of the unique reactions that aromatic molecules undergo.

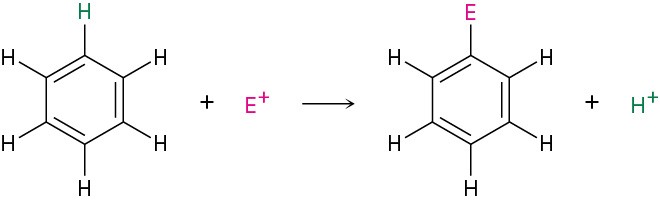

The most common reaction of aromatic compounds is electrophilic aromatic substitution, in which an electrophile (E+) reacts with an aromatic ring and substitutes for one of the hydrogens. The reaction is characteristic of all aromatic rings, not just benzene and substituted benzenes. In fact, the ability of a compound to undergo electrophilic substitution is a good test of aromaticity.

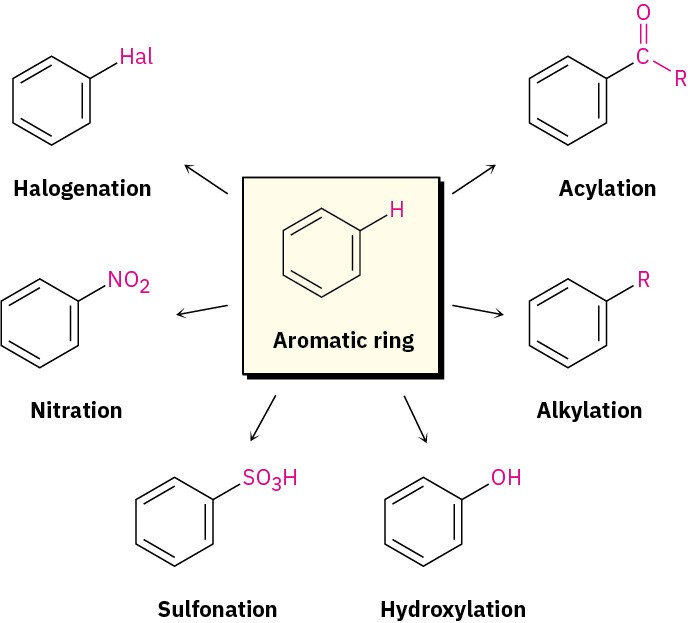

Many different substituents can be introduced onto an aromatic ring through electrophilic substitution. To list some possibilities, an aromatic ring can be substituted by a halogen (– Cl, –Br, –I), a nitro group (–NO2), a sulfonic acid group (–SO3H), a hydroxyl group (–OH), an alkyl group (–R), or an acyl group (–COR). Starting from only a few simple materials, it’s possible to prepare many thousands of substituted aromatic compounds.