10 Chapter 10 – Organohalides Solutions to Problems

Chapter 10 – Organohalides

Solutions to Problems

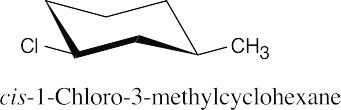

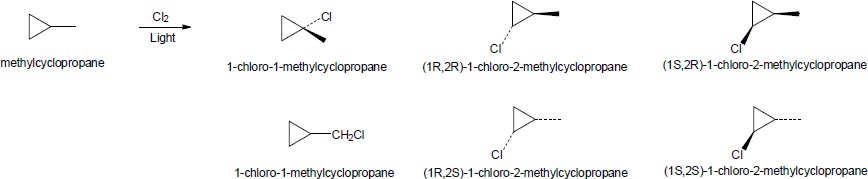

| 10.1 |

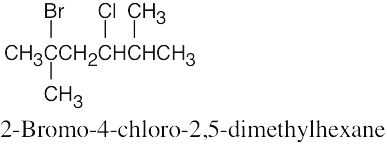

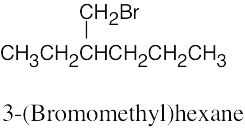

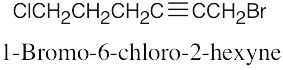

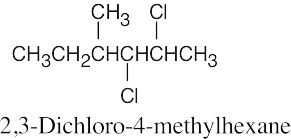

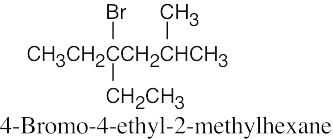

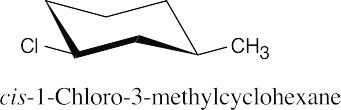

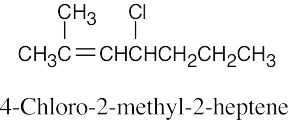

The rules that were given for naming alkanes in Section 3.4 are used for alkyl halides. A halogen is treated the same as an alkyl substituent but is named as a halo group.

|

| 10.3 |

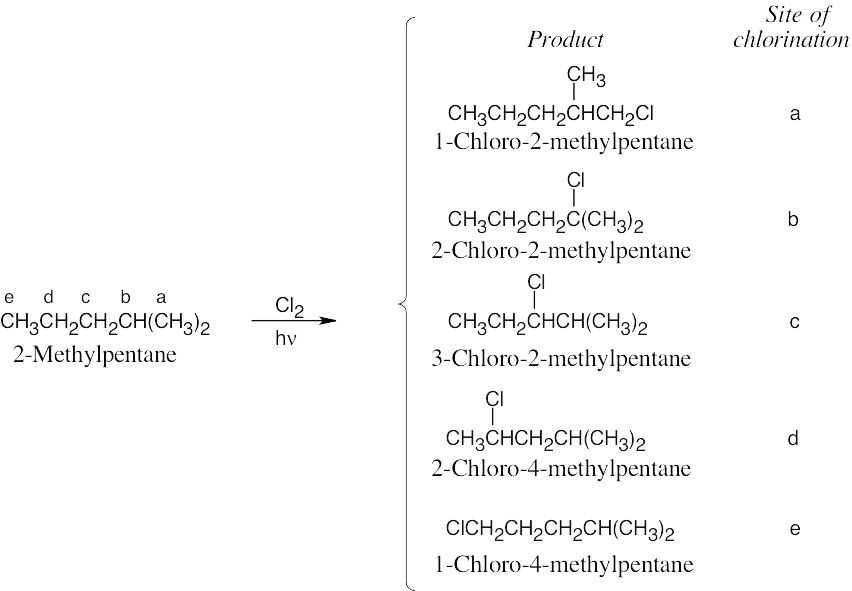

Chlorination at sites b and e yields achiral products. The products of chlorination at sites a, c and d are chiral; each product is formed as a racemic mixture of enantiomers. |

| 10.6 |

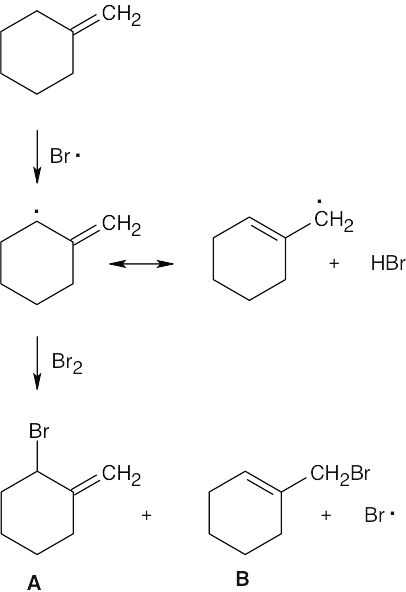

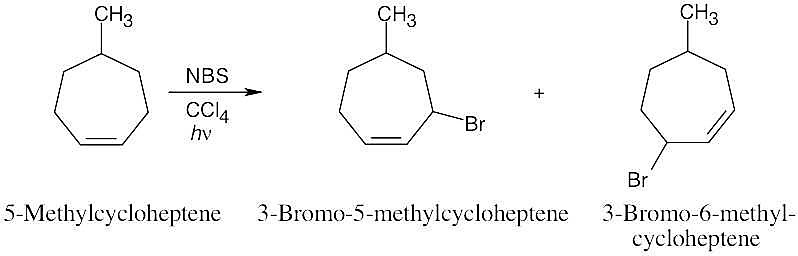

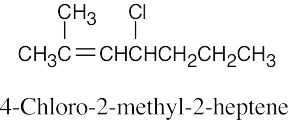

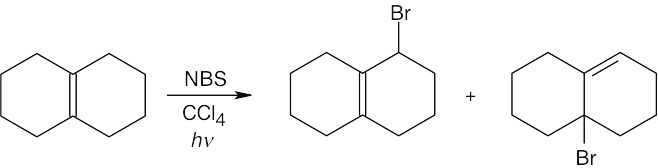

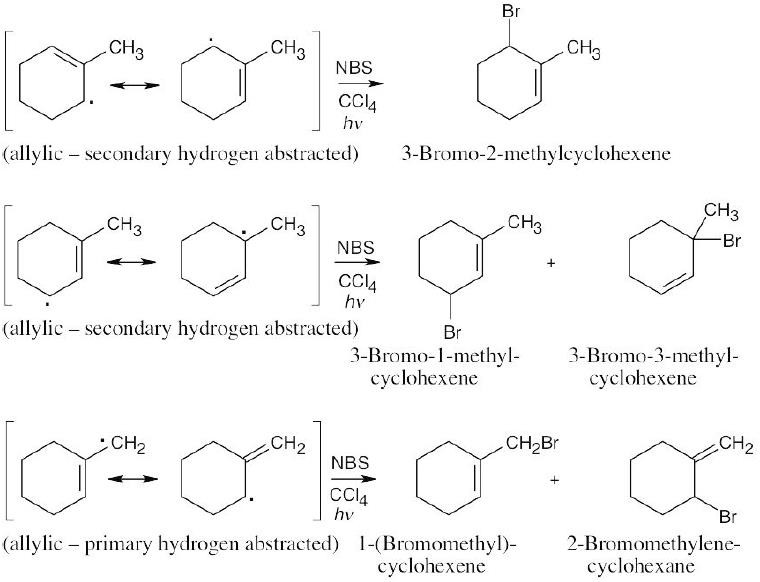

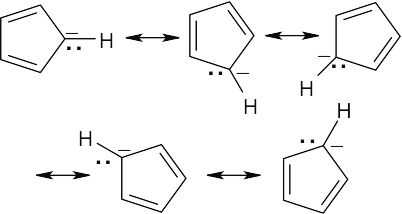

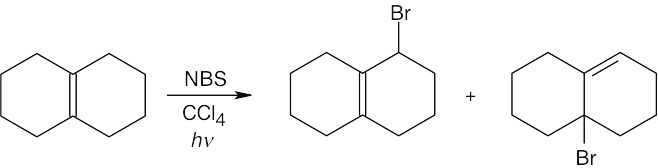

1) Abstraction of hydrogen by a bromine radical yields an allylic radical.

2) The allylic radical reacts with Br2 to produce A and B.

Product B is favored because the reaction at the primary end of the allylic radical yields a product with a trisubstituted double bond. |

| 10.7 |

| (a)

|

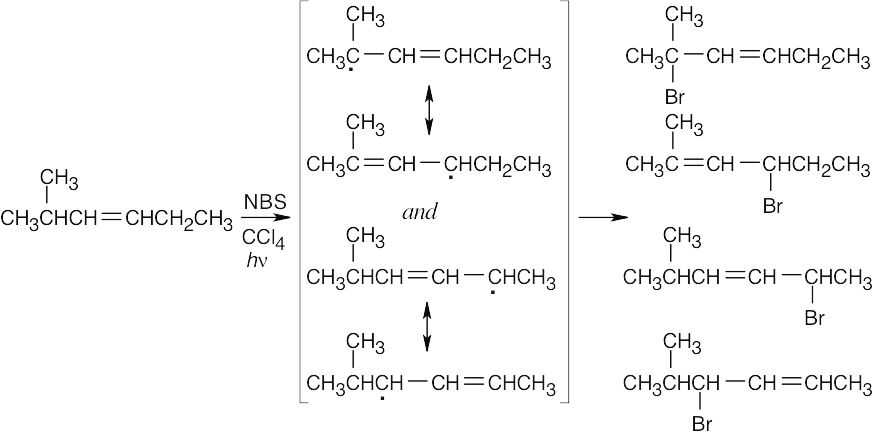

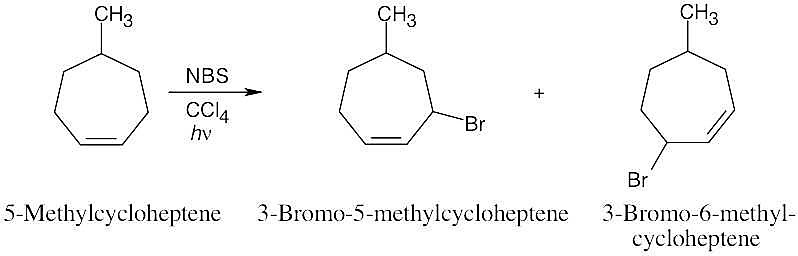

| (b)

|

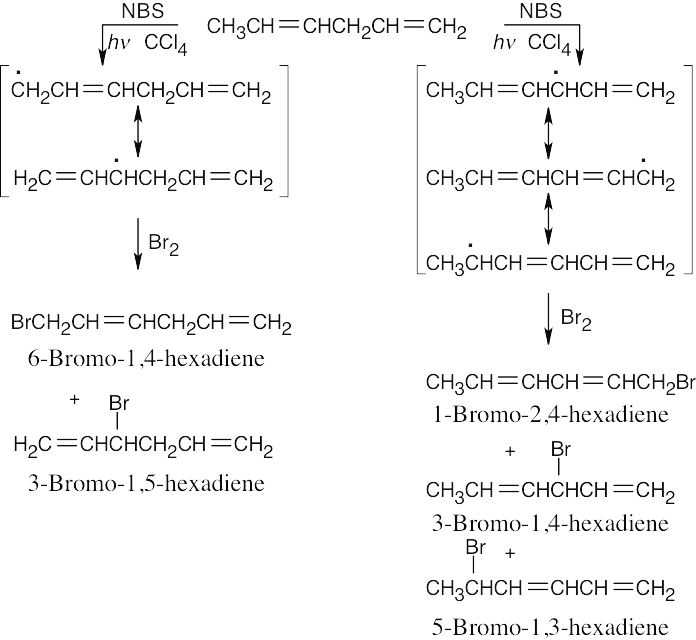

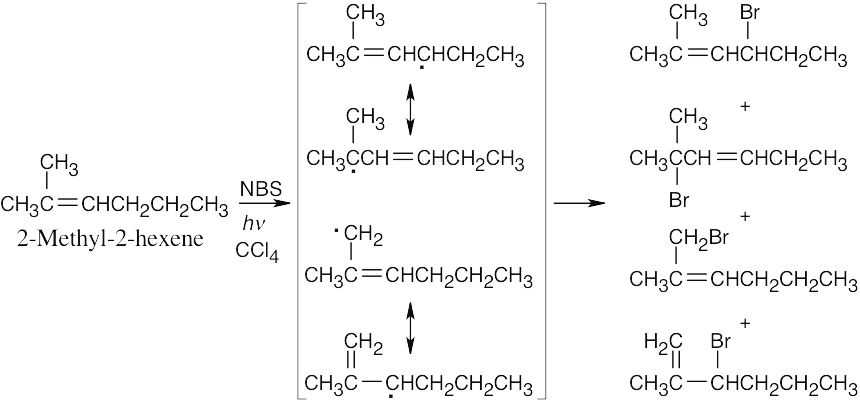

Two different allylic radicals can form, and four different bromohexenes can be produced. |

| 10.8 |

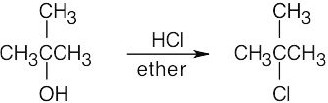

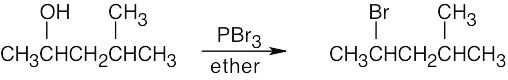

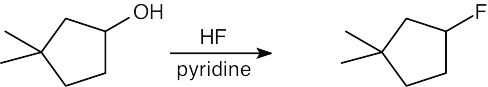

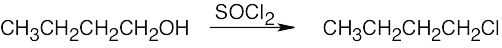

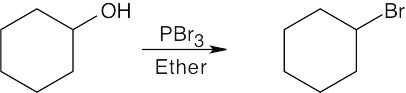

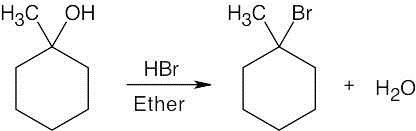

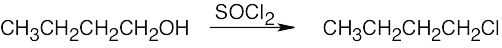

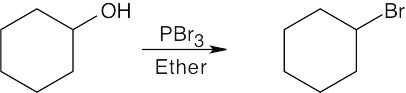

Remember that halogen acids are used for converting tertiary alcohols to alkyl halides. PBr3 and SOCl2 are used for converting secondary and primary alcohols to alkyl halides. (CH3CH2)2NSF3 and HF in pyridine can be used to form alkyl fluorides.

|

| 10.9 |

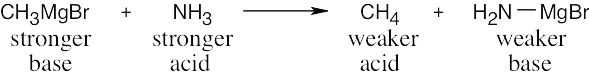

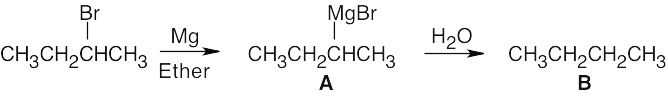

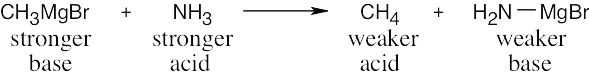

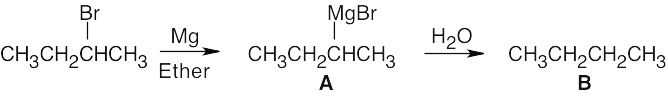

Table 9.1 shows that the pKa of CH3–H is 60. Since CH4 is a very weak acid, –:CH3 is a very strong base. Alkyl Grignard reagents are similar in base strength to –:CH3, but alkynyl Grignard reagents are somewhat weaker bases. Both reactions (a) and (b) occur as written.

| (a)

|

| (b)

|

|

| 10.10 |

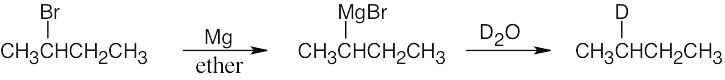

Just as Grignard reagents react with proton donors to convert R–MgX into R–H, they also react with deuterium donors to convert R–MgX into R–D. In this case:

|

| 10.11 |

| (a) |

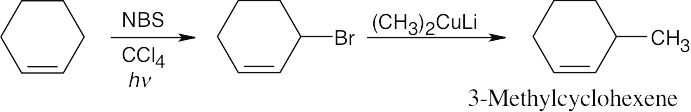

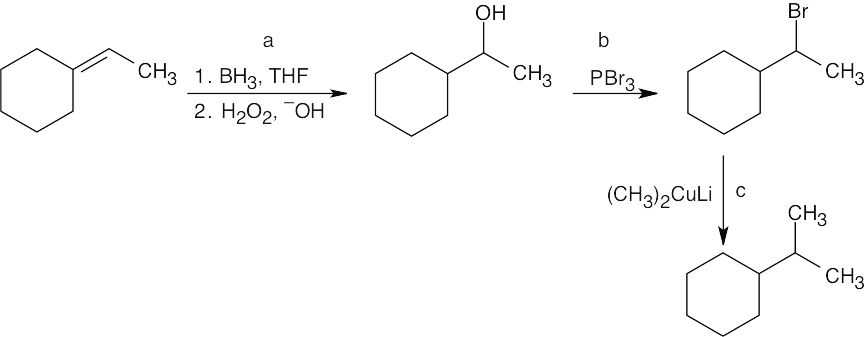

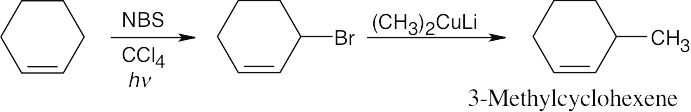

The methyl group has an allylic relationship to the double bond. Thus, an organometallic coupling reaction between 3-bromocyclohexene and lithium dimethylcopper gives the desired product. 3-Bromocyclohexene can be formed by allylic bromination of cyclohexene with NBS.

|

| (b) |

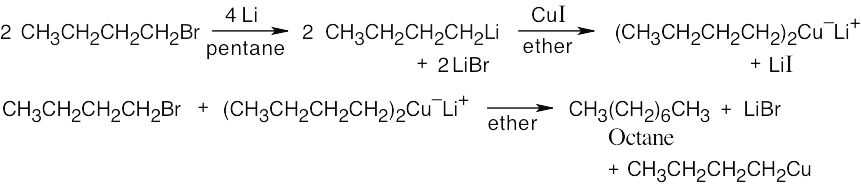

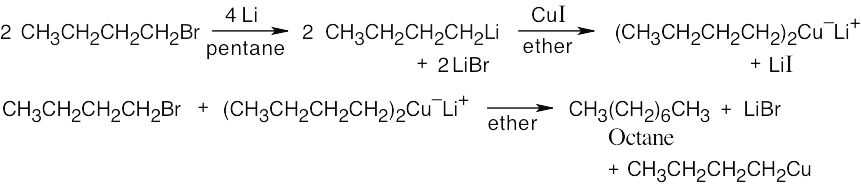

We are asked to synthesize an eight–carbon product from a four–carbon starting material. Thus, an organometallic coupling reaction between 1-bromobutane and lithium dibutylcopper gives octane as the product. The Gilman reagent is formed from 1-bromobutane.

|

| (c) |

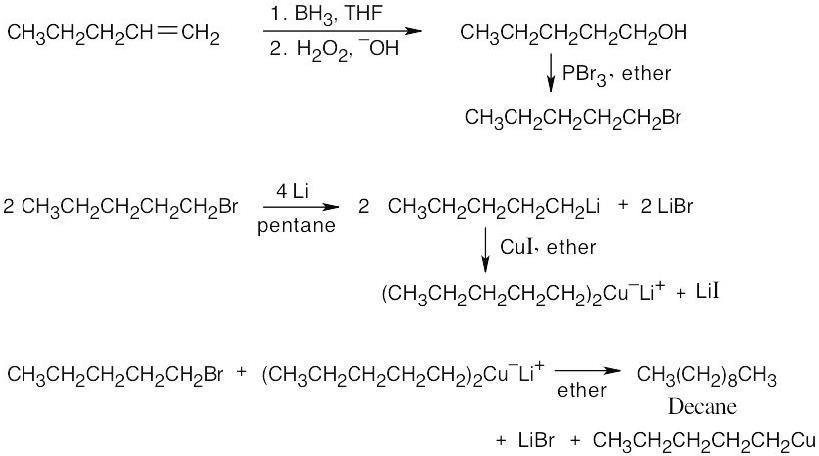

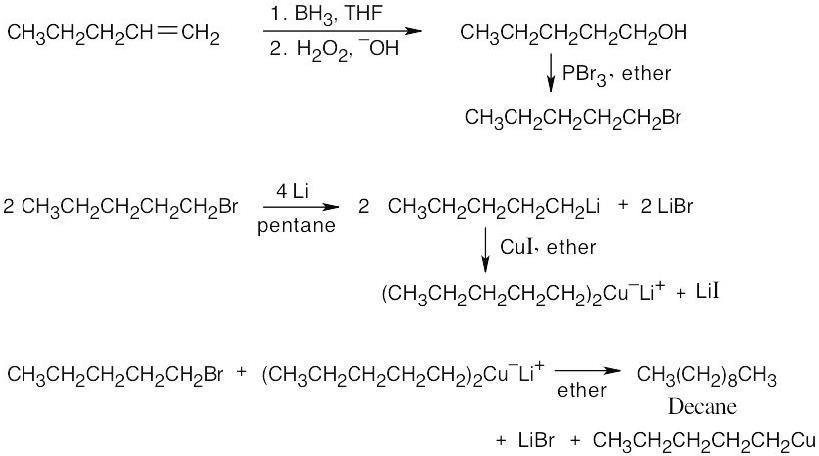

The synthesis in (b) suggests a route to the product. Decane can be synthesized from 1-bromopentane and lithium dipentylcopper. 1-Bromopentane is formed by hydroboration of 1-pentene, followed by treatment of the resulting alcohol with PBr3.

|

|

| 10.12 |

| (a) |

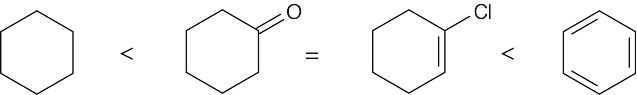

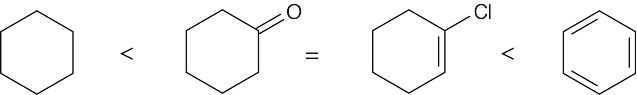

As described in Worked Example 10.2, the oxidation level of a compound can be found by adding the number of C–O, C–N, and C–X bonds and subtracting the number of C–H bonds. Cyclohexane, the first compound shown, has 12 C–H bonds, and has an oxidation level of –12. Cyclohexanone has 2 C–O bonds (from the double bond) and 10 C–H bonds, for an oxidation level of –8. 1 – Chlorocyclohexene has one C–Cl bond and 9 C–H bonds, and also has an oxidation level of –8. Benzene has 6 C–H bonds, for an oxidation level of –6.

In order of increasing oxidation level:

|

| (b) |

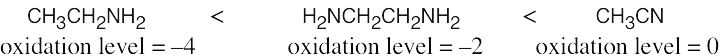

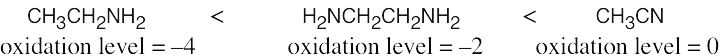

|

|

| 10.13 |

| (a) |

The aldehyde carbon of the reactant has an oxidation level of 1 (2 C–O bonds minus 1 C–H bond). The alcohol carbon of the product has an oxidation level of –1 (1 C–O bond minus 2 C–H bonds). The reaction is a reduction because the oxidation level of the product is lower than the oxidation level of the reactant. |

| (b) |

The oxidation level of the upper carbon of the double bond in the reactant changes from 0 to +1 in the product; the oxidation level of the lower carbon of the double bond changes from 0 to –1. The total oxidation level, however, is the same for both product and reactant, and the reaction is neither an oxidation nor a reduction. |

|

Additional Problems

Visualizing Chemistry

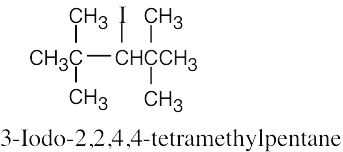

| 10.14 |

| (a)

|

(b)

|

|

| 10.15 |

| (a)

|

| (b)

|

|

| 10.16 |

The name of the compound is (R)-2-bromopentane. Reaction of (S)-2-pentanol with PBr3 to form (R)-2-bromopentane occurs with a change in stereochemistry because the configuration at the chirality center changes from S to R. |

Mechanism Problems

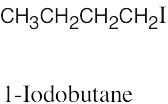

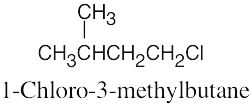

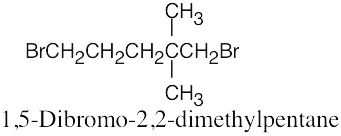

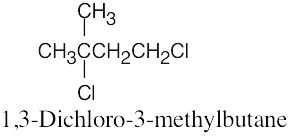

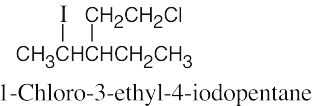

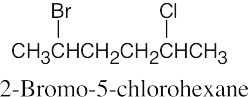

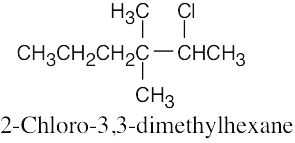

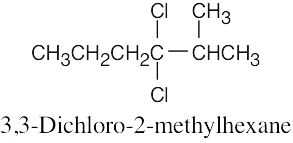

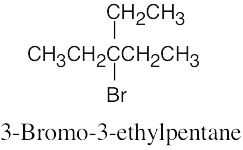

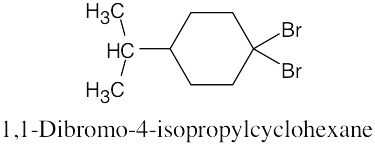

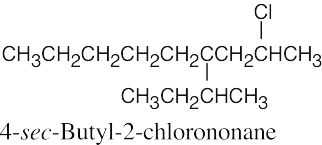

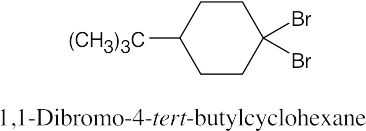

Naming Alkyl Halides

| 10.20 |

| (a) |

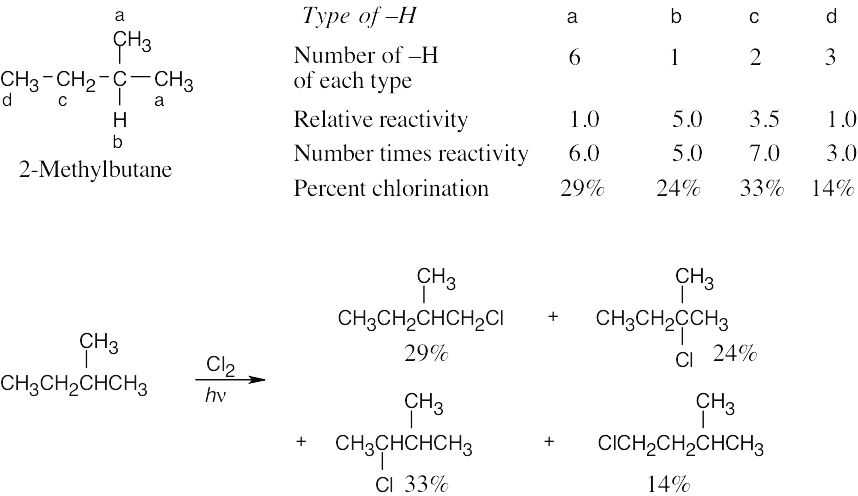

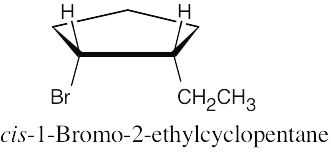

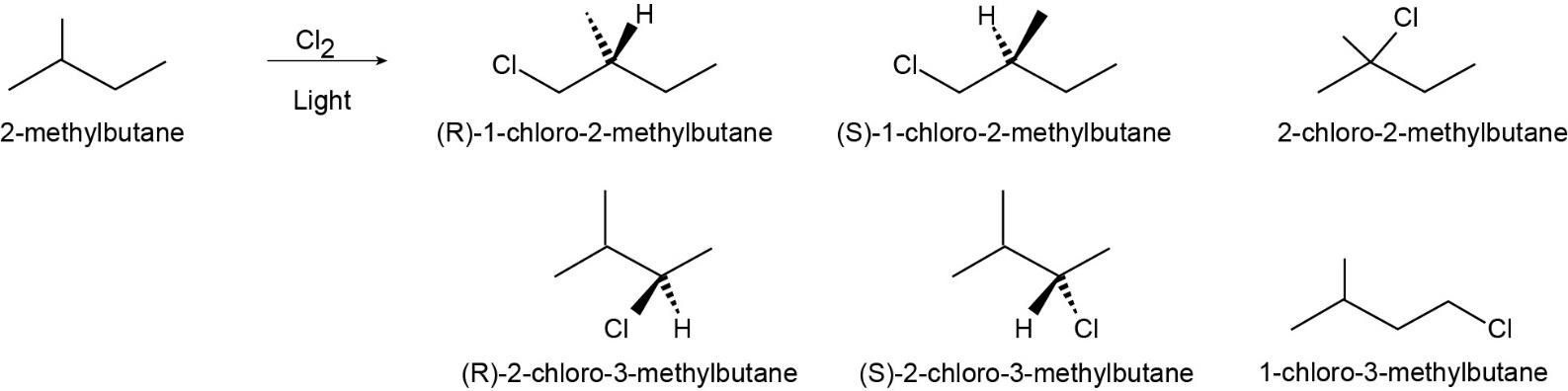

2-methylbutane

There are six different products. Four of the compounds are chiral and optically active.

|

| (b) |

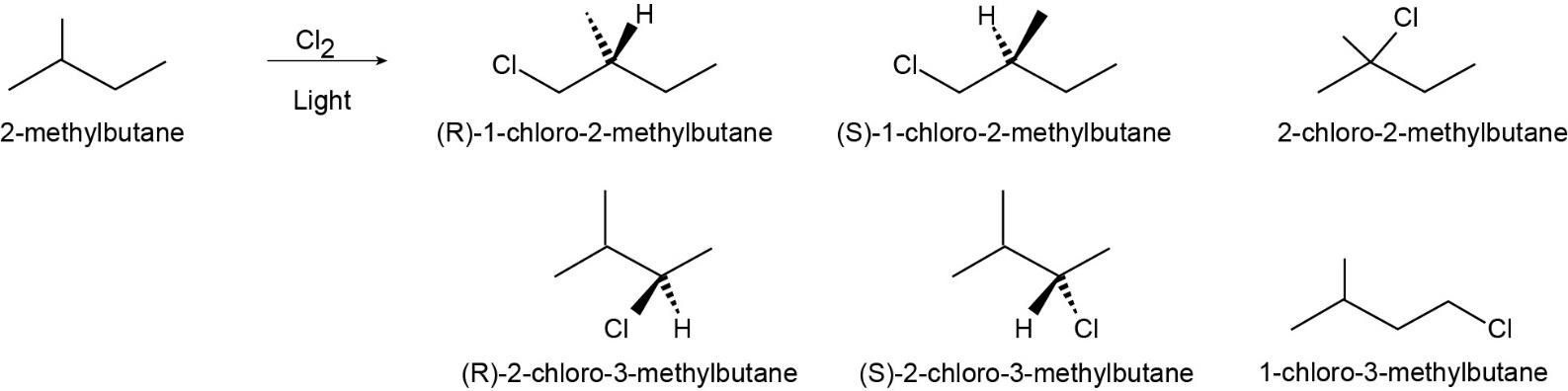

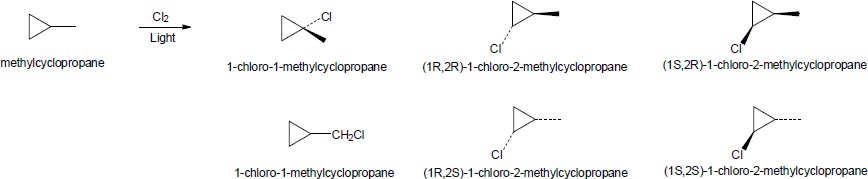

methylcyclopropane

There are six different products. All of the compounds whose names include the absolute configuration (R and/or S) in their name are chiral and optically active.

|

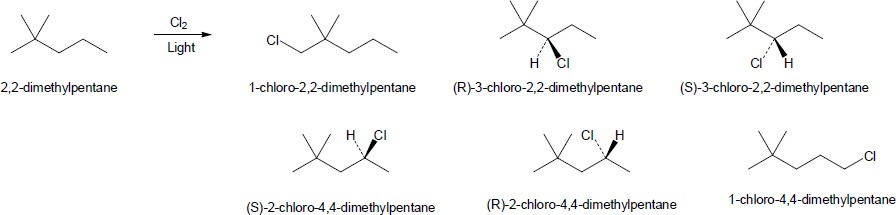

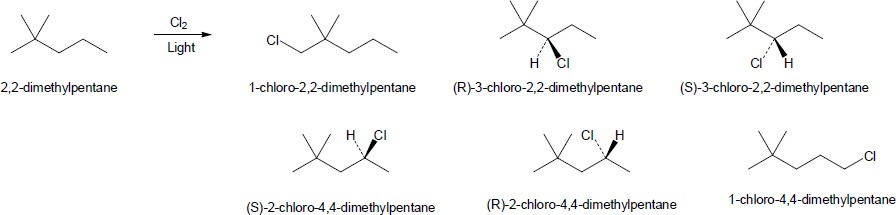

| (c) |

2,2-dimethylpentane

There are six different products. All of the compounds whose names include the absolute configuration (R or S) in their name are chiral and optically active.

|

|

Synthesizing Alkyl Halides

| 10.21 |

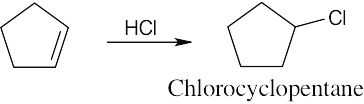

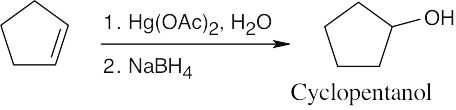

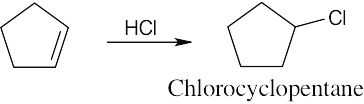

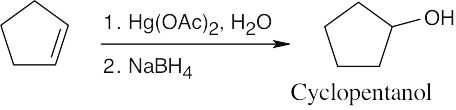

| (a)

|

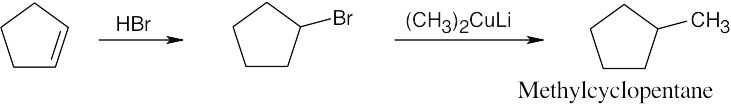

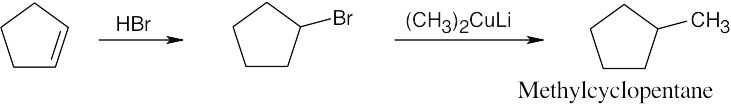

| (b)

|

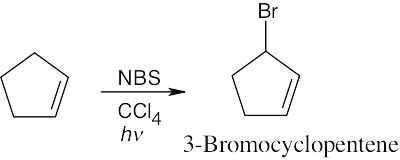

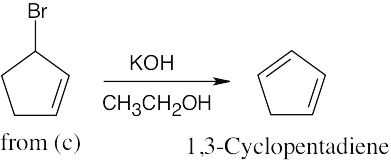

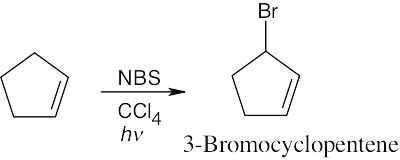

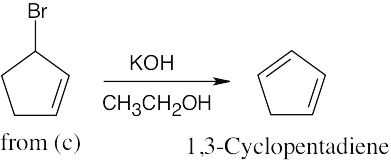

| (c)

|

| (d)

Hydroboration/oxidation can also be used to form cyclopentanol. |

| (e)

|

| (f)

|

|

| 10.22 |

| (a)

|

| (b)

|

| (c)

The major product contains a tetrasubstituted double bond, and the minor product contains a trisubstituted double bond. |

| (d)

|

| (e)

|

| (f)

|

| (g)

|

|

| 10.23 |

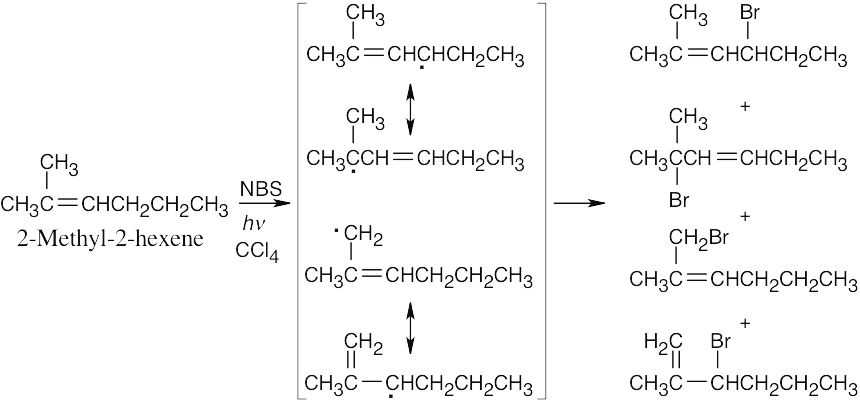

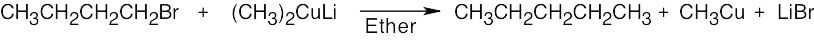

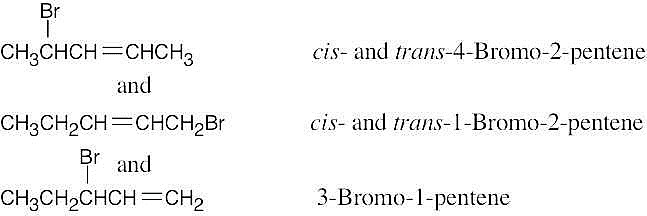

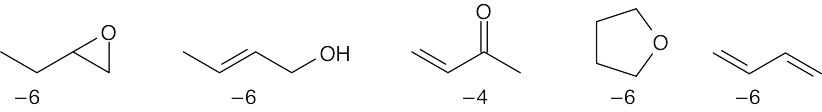

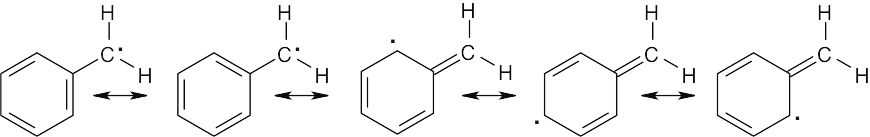

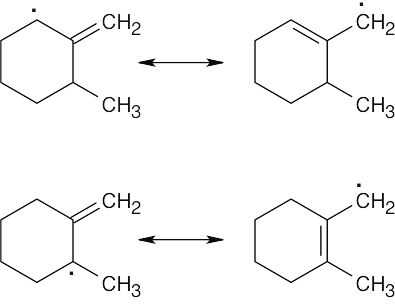

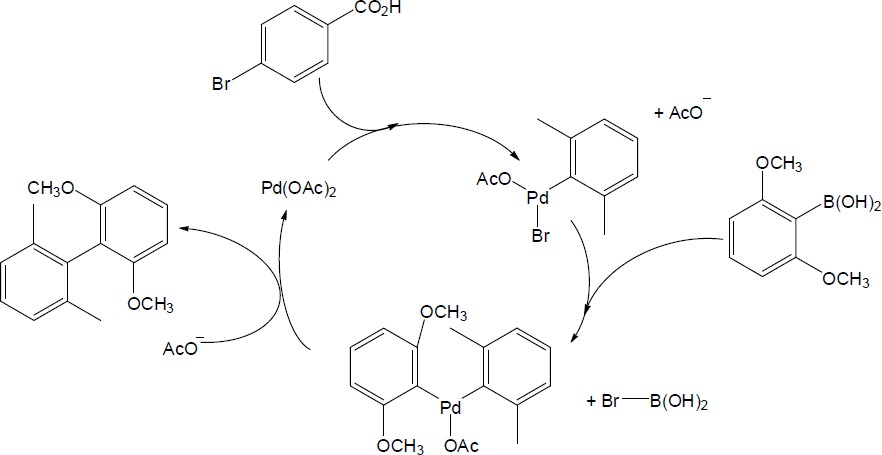

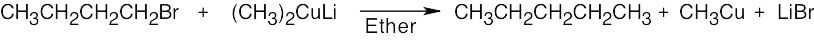

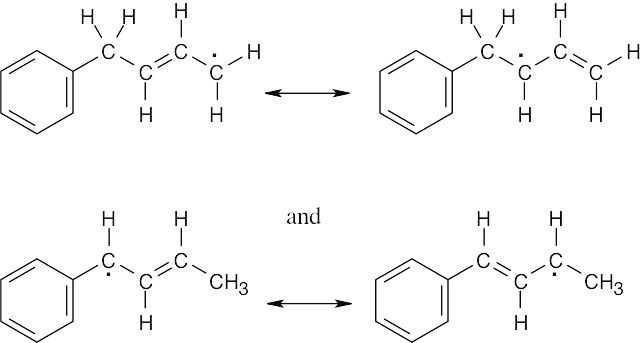

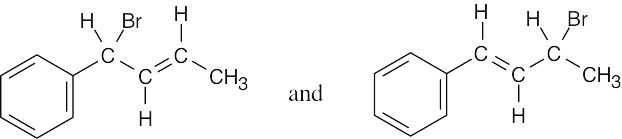

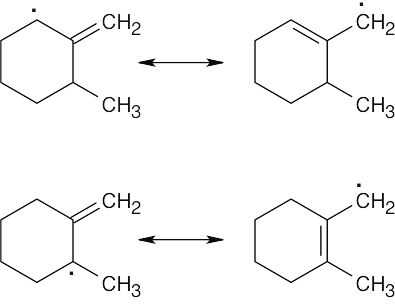

Abstraction of hydrogen by Br• can produce either of two allylic radicals. The first radical, resulting from abstraction of a secondary hydrogen, is more likely to be formed.

Reaction of the radical intermediates with a bromine source leads to a mixture of products:

The major product is 4-bromo-2-pentene, instead of the desired product, 1-bromo-2- pentene. |

|

| 10.24 |

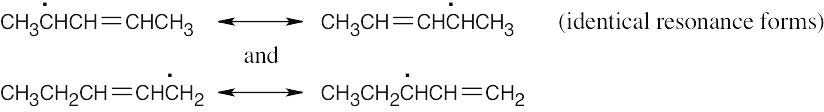

Three different allylic radical intermediates can be formed. Bromination of these intermediates can yield as many as five bromoalkenes. This is definitely not a good reaction to use in a synthesis even if the products could be separated.

|

| 10.25 |

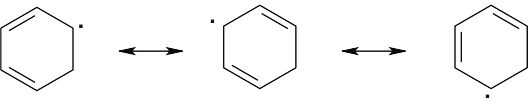

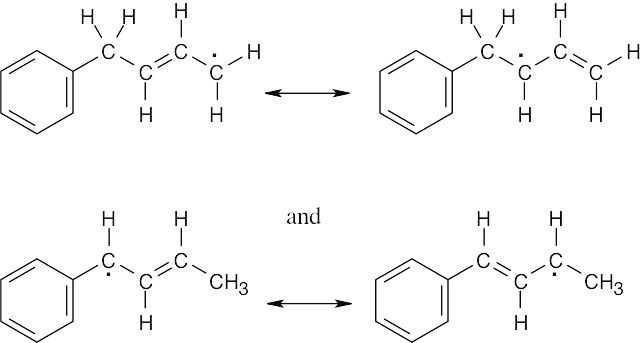

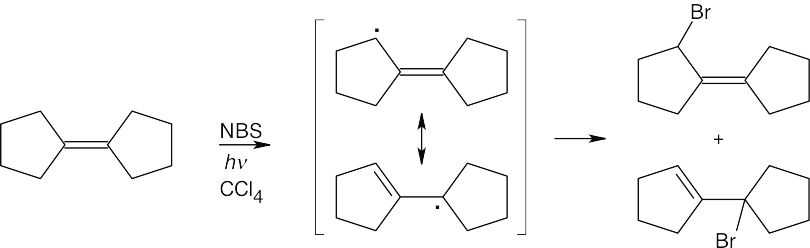

The intermediate on the right is more stable because the unpaired electron is delocalized over more atoms than in the intermediate on the left, and the resulting products should predominate. |

| 10.26 |

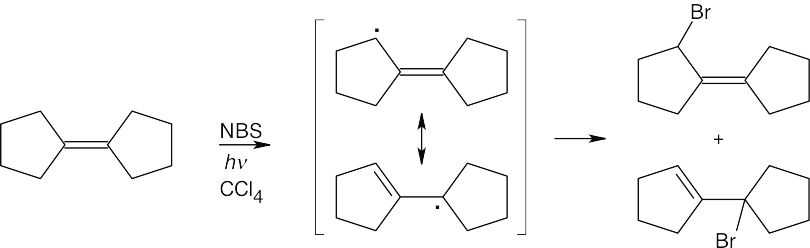

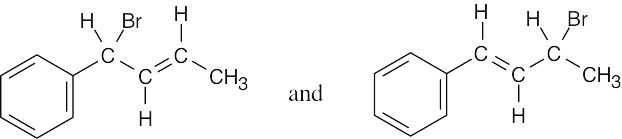

Two allylic radicals can form:

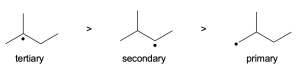

The second radical is much more likely to form because it is both allylic and benzylic, and it yields the following products:

|

|

Oxidation and Reduction

| 10.27 |

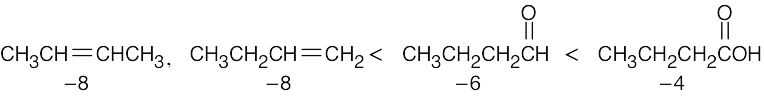

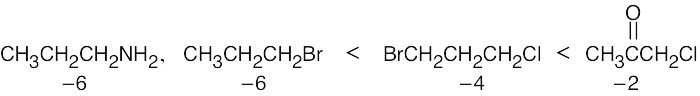

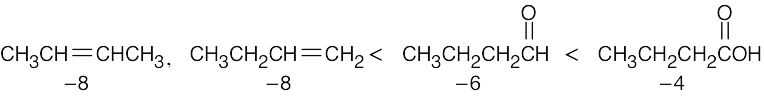

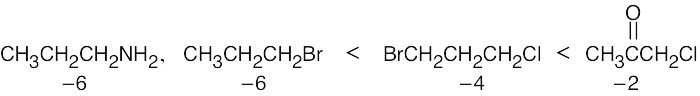

Remember that the oxidation level is found by subtracting the number of C–H bonds from the number of C–O, C–N, and C–X bonds. The oxidation levels are shown beneath the structures.

In order of increasing oxidation level:

| (a)

|

| (b)

|

|

| 10.28 |

All of the compounds except 3 (which is more oxidized) have the same oxidation level. |

| 10.29 |

| (a) |

This reaction is an oxidation. |

| (b) |

The reaction is neither an oxidation nor a reduction because the oxidation level of the reactant is the same as the oxidation level of the product. |

| (c) |

This reaction is a reduction. |

|

General Problems

| 10.30 |

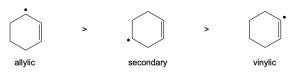

The general trend for radical stability is shown below.

Hint:

|

| 10.31 |

Table 6.3 shows that the bond dissociation energy for C6H5CH2–H is 375 kJ/mol. This value is comparable in size to the bond dissociation energy for a bond between carbon and an allylic hydrogen, and thus it is relatively easy to form the C6H5CH2• radical. The high bond dissociation energy for formation of C6H5•, 472 kJ/mol, indicates the bromination on the benzene ring will not occur. The only product of reaction with NBS is C6H5CH2Br. |

| 10.34 |

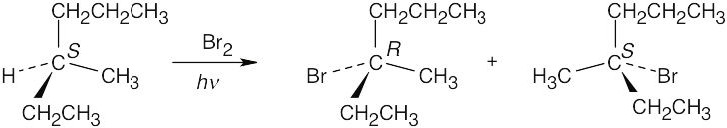

Abstraction of a hydrogen atom from the chirality center of (S)-3-methylhexane produces an achiral radical intermediate, which reacts with bromine to form a 1:1 mixture of R and S enantiomeric, chiral bromoalkanes. The product mixture is optically inactive. |

| 10.35 |

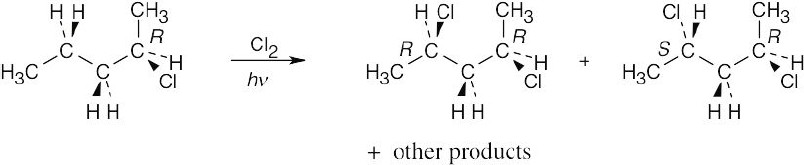

Abstraction of a hydrogen atom from carbon 4 yields a chiral radical intermediate. Reaction of this intermediate with chlorine does not occur with equal probability from each side, and the two diastereomeric products are not formed in a 1:1 ratio. The first product is optically active, and the second product is a meso compound. |

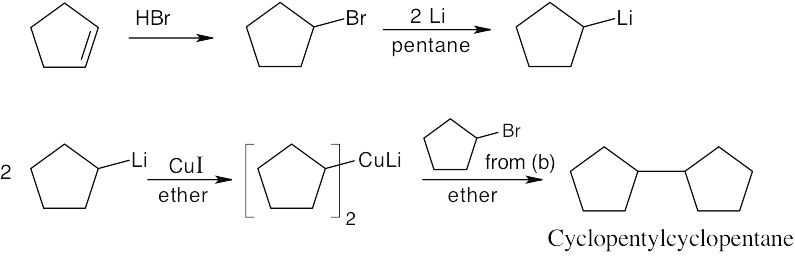

| 10.36 |

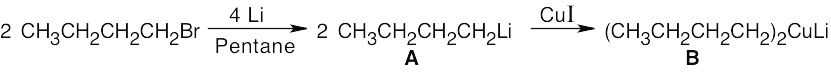

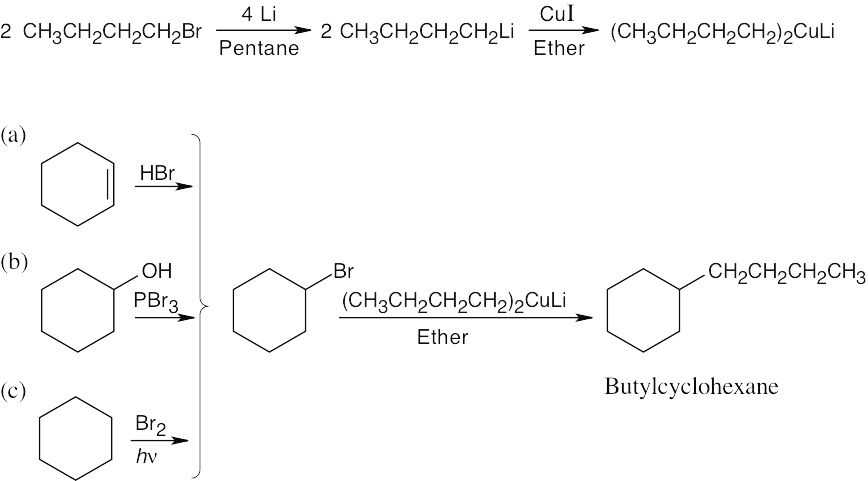

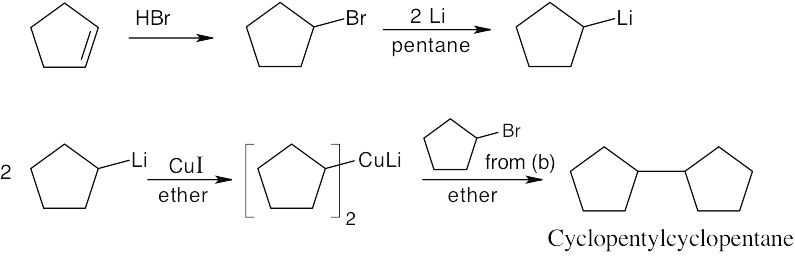

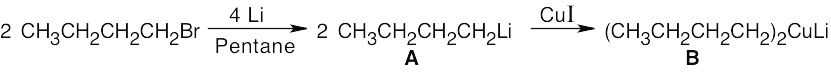

All these reactions involve addition of a dialkylcopper reagent [(CH3CH2CH2CH2)2CuLi] to the same alkyl halide. The dialkylcopper is prepared by treating 1-bromobutane with lithium, followed by addition of CuI:

|

| 10.37 |

| (a) Fluoroalkanes do not usually form Grignard reagents. |

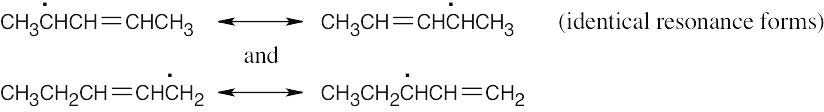

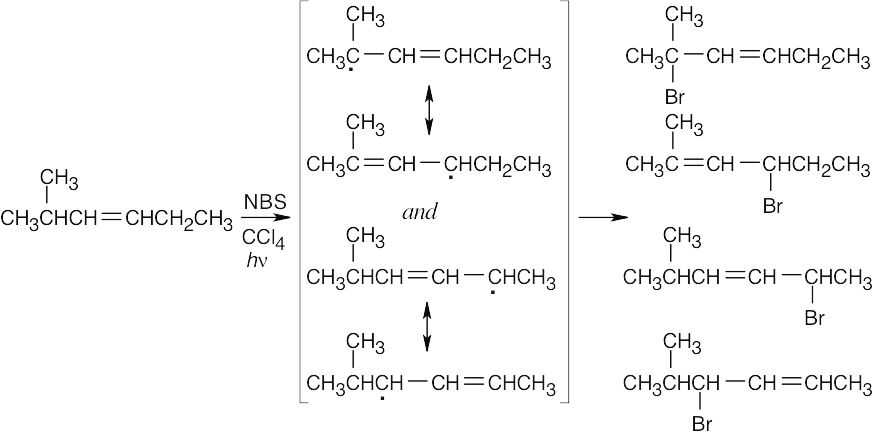

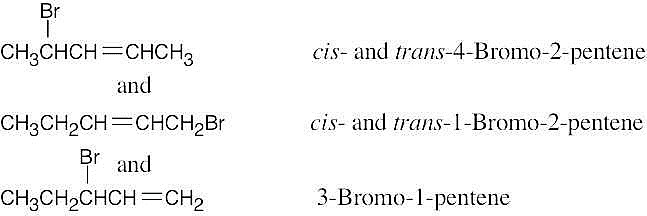

| (b) Two allylic radicals can be produced.

Instead of a single product, as many as four bromoalkene products may result.

(c) Dialkylcopper reagents do not react with fluoroalkanes. |

|

| 10.38 |

A Grignard reagent cannot be prepared from a compound containing an acidic functional group because the Grignard reagent is immediately quenched by the proton source. For example, the –CO2H, –OH, –NH2, and RC≡CH functional groups are too acidic to be used for preparation of a Grignard reagent. BrCH2CH2CH2NH2 is another compound that does not form a Grignard reagent. |

| 10.39 |

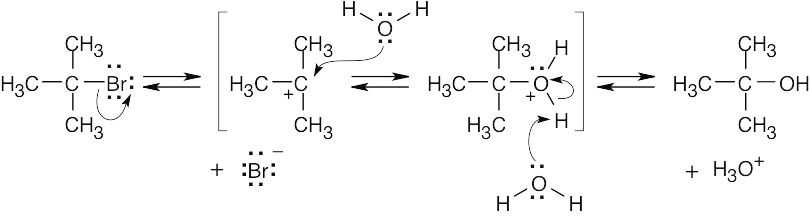

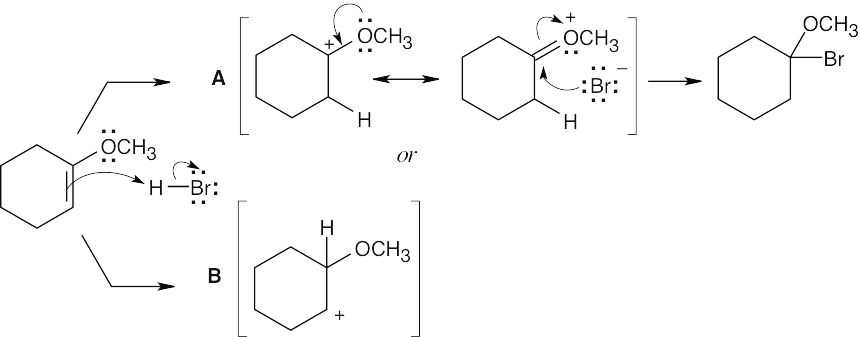

Reaction of the ether with HBr can occur by either path A or path B. Path A is favored because its cation intermediate can be stabilized by resonance. |

| 10.41 |

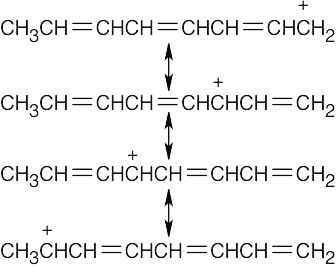

As we saw in Chapter 7, tertiary carbocations (R3C+) are more stable than either secondary or primary carbocations, due to the ability of the three alkyl groups to stabilize a positive charge. If the substrate is also allylic, as in the case of H2C=CHC(CH3)2Br, positive charge can be further delocalized. Thus, H2C=CHC(CH3)2Br should form a carbocation faster than (CH3)3CBr because the resulting carbocation is more stable. |

| 10.42 |

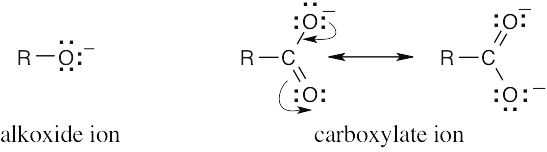

Carboxylic acids are more acidic than alcohols because the negative charge of a carboxylate ion is stabilized by resonance. This resonance stabilization favors formation of carboxylate anions over alkoxide anions, and increases Ka for carboxylic acids.

Alkoxide anions are not resonance stabilized. |

| 10.44 |

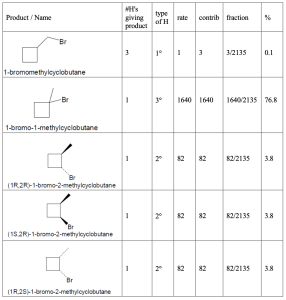

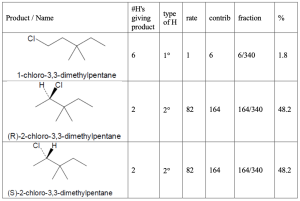

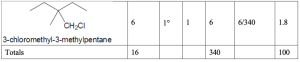

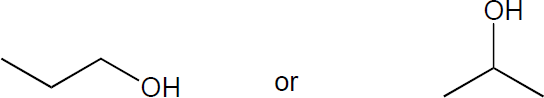

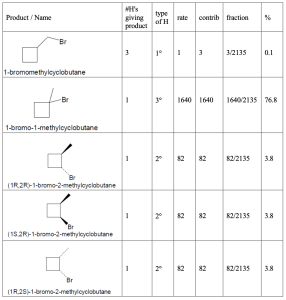

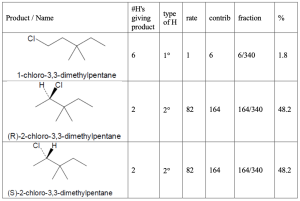

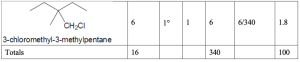

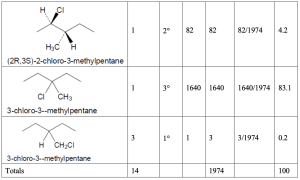

Hint: When solving these problems it is easiest to create a table. First, all of the unique products must be identified. Each product will have a different name. Then one needs first determine the number of hydrogens that will lead to each different product. As a double check, the sum of the number of hydrogens leading to each product must be equal to the total number of hydrogens in the starting material. Once identified, the type of each hydrogen (1°, 2°, 3°) must be assigned. The rate for each type of hydrogen (1:82:1640 for 1°:2°:3° hydrogens, respectively) should be multiplied by number of hydrogens to give the contribution of each product to the whole. That fraction is then calculated by dividing each individual contribution by the total contribution and that fraction converted into a percentage.

| (a) methylcyclobutane

|

| (b) 3,3-dimethylpentane

|

| (c) 3-methylpentane

|

|

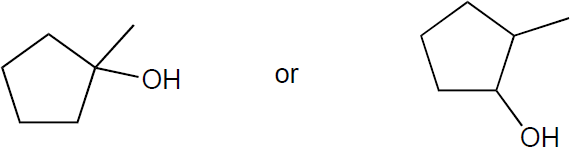

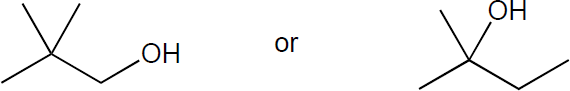

| 10.45 |

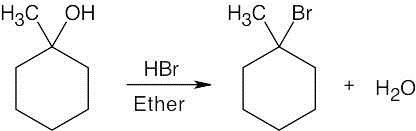

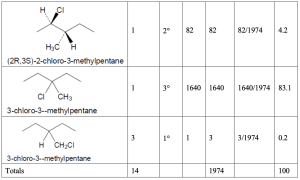

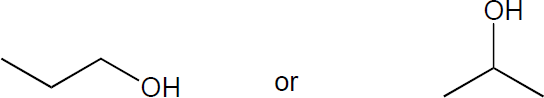

| (a) |

The primary alcohol would go exclusively through an SN2 mechanism. This secondary alcohol will undergo a mixture of SN1 and SN2 substitution. However, formation of a secondary carbocation is relatively slow, as is the SN2 reaction compared to the primary alcohol. Thus, the primary alcohol will be the faster reaction.

|

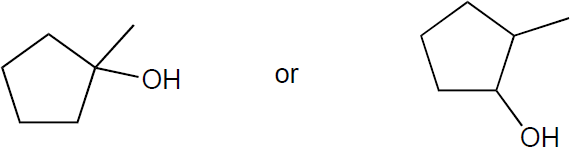

| (b) |

Tertiary alcohols undergo the fastest of SN1 reactions through a tertiary carbocation, while a secondary alcohol is relatively slow for SN2 because of the sterics of the substrate. Thus, the tertiary alcohol would be expected to react faster.

|

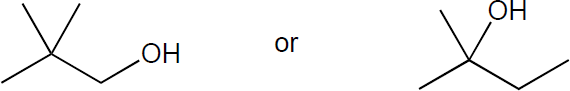

| (c) |

Tertiary alcohols undergo the fastest of SN1 reactions through a tertiary carbocation, while the primary alcohol of neopentyl alcohol is one of the slowest SN2 substrates for substitution because of the sterics on the tert-butyl group. Thus, the tertiary alcohol would be expected to react faster.

|

|

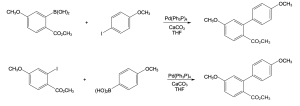

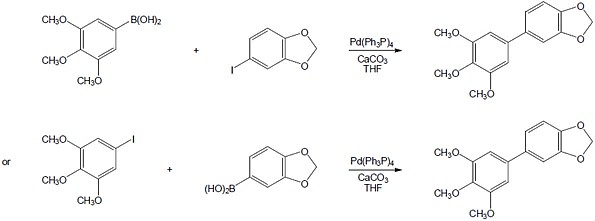

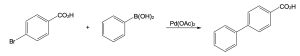

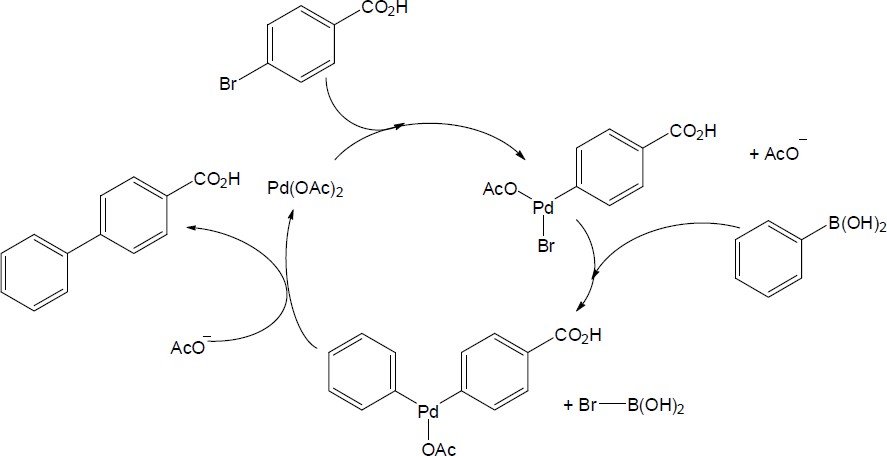

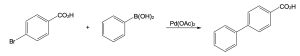

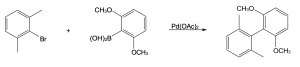

| 10.46 |

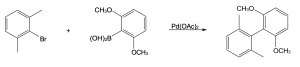

| (a)

Catalytic cycle:

|

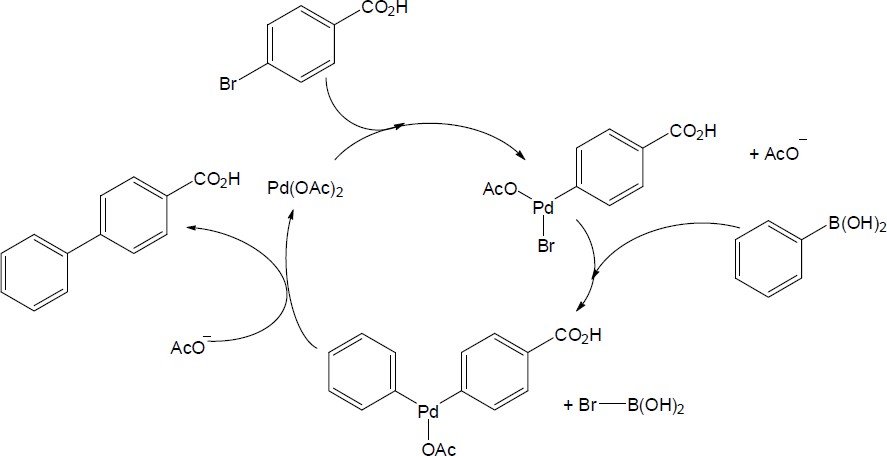

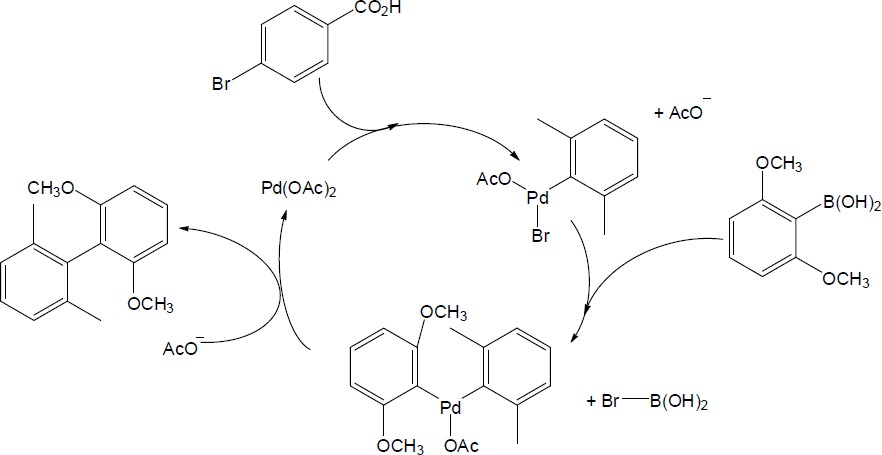

| (b)

Catalytic cycle:

|

|

This file is copyright 2023, Rice University. All Rights Reserved.