9 Chapter 9 – Alkynes: An Introduction to Organic Synthesis Solutions to Problems

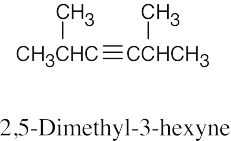

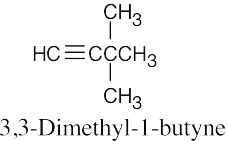

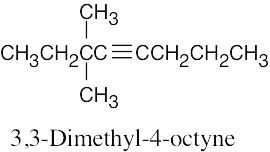

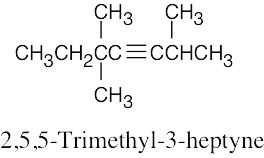

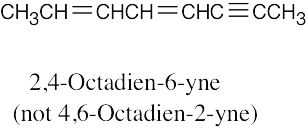

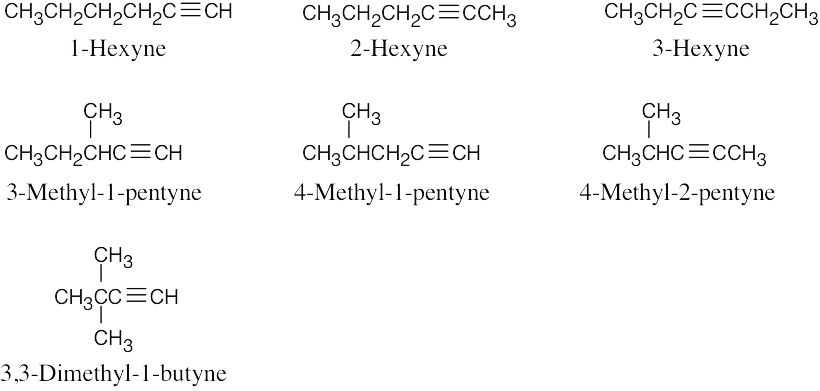

| 9.1 | The rules for naming alkynes are almost the same as the rules for naming alkenes. The suffix –yne is used, and compounds containing both double bonds and triple bonds are –enynes, with the double bond taking numerical precedence. | |

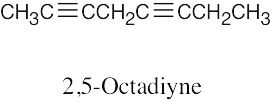

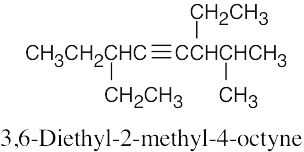

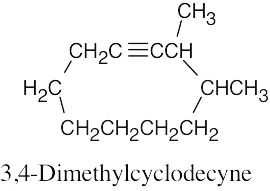

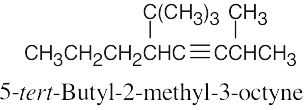

| (a) |  |

|

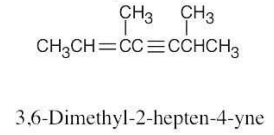

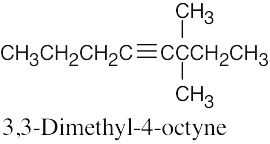

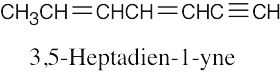

| (b) |  |

|

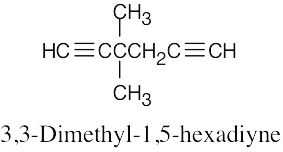

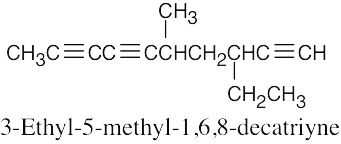

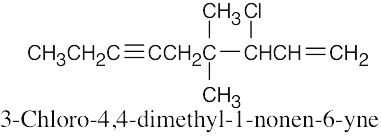

| (c) |  |

|

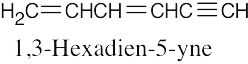

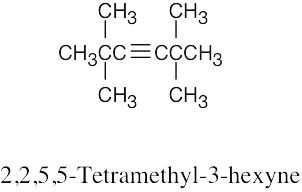

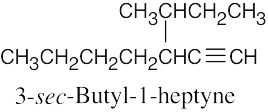

| (d) |  |

|

| (e) |  |

|

| 9.2 |  |

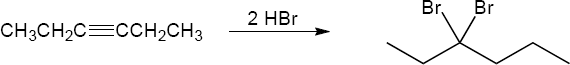

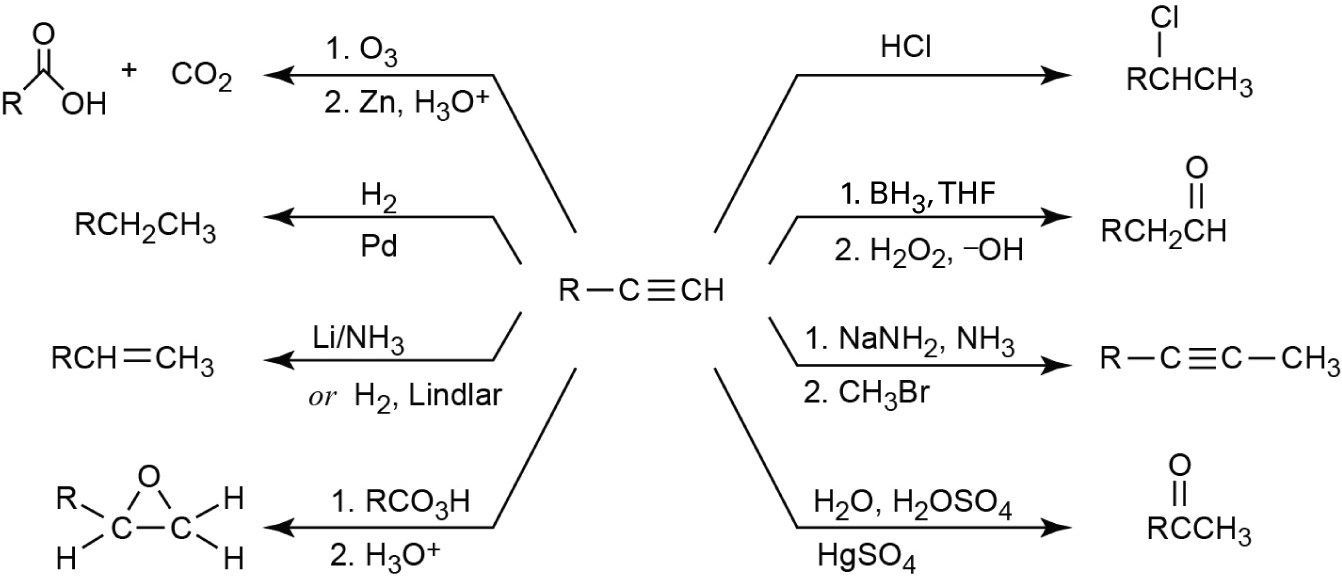

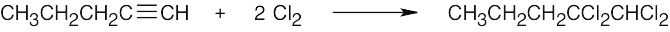

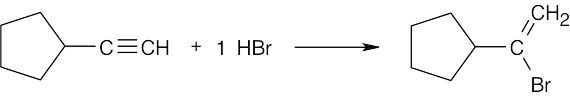

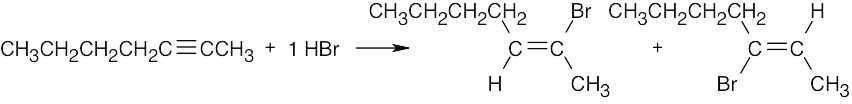

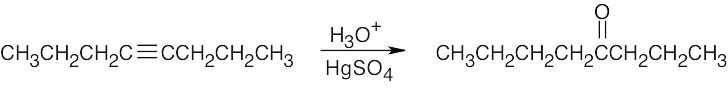

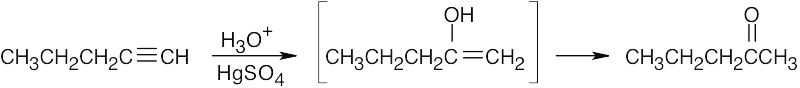

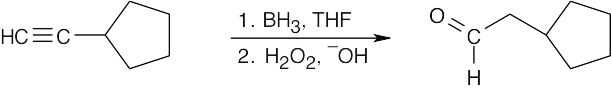

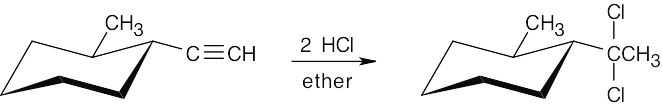

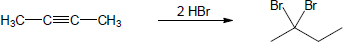

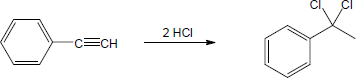

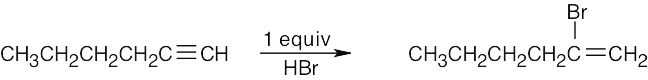

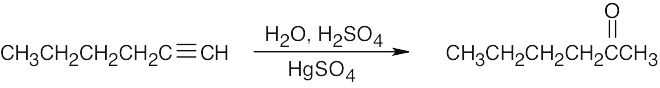

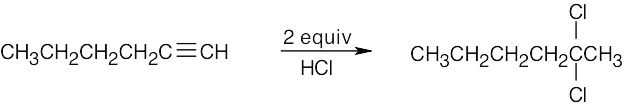

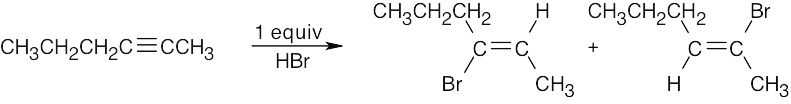

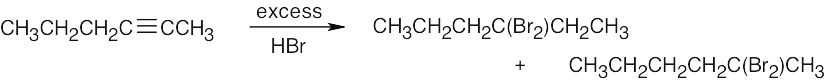

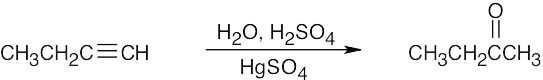

| 9.3 | Markovnikov addition is observed with alkynes as well as with alkenes. | |

| (a) |  |

|

| (b) |  |

|

| (c) |

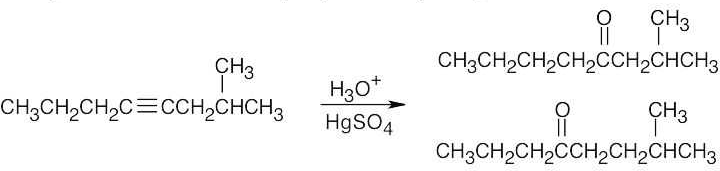

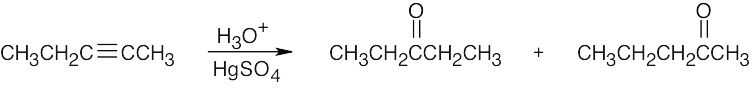

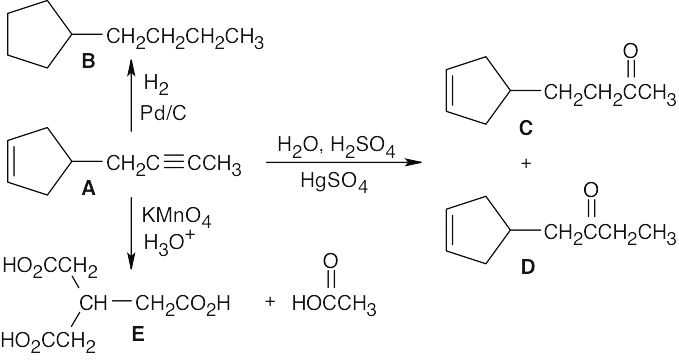

Two products result from addition to an internal alkyne. |

|

| 9.4 |

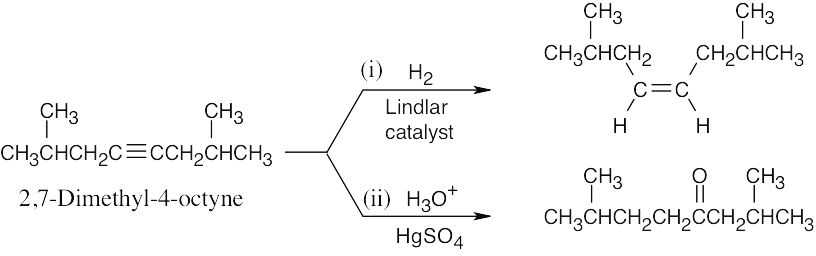

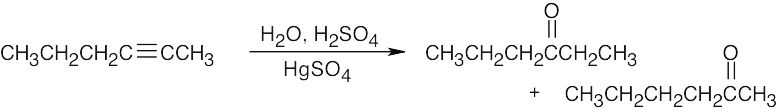

This symmetrical internal alkyne yields only one product. |

Two ketone products result from hydration of 2-methyl-4-octyne. |

| 9.5 | (a) |  |

| (b) |

The desired ketone can be prepared only as part of a product mixture. |

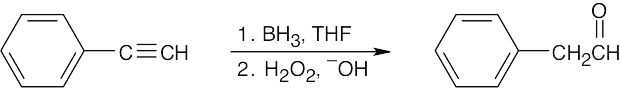

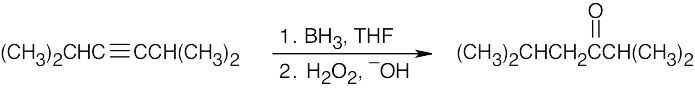

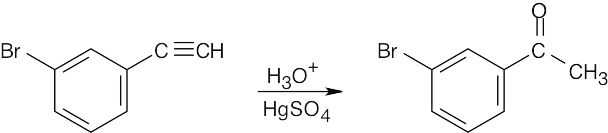

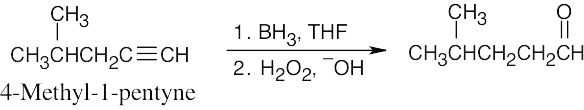

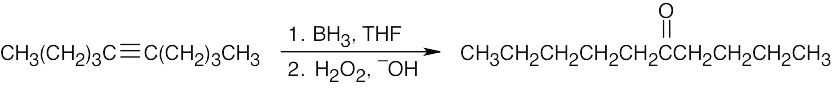

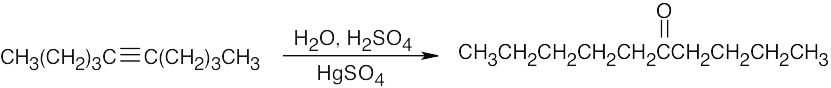

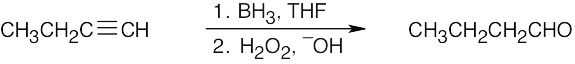

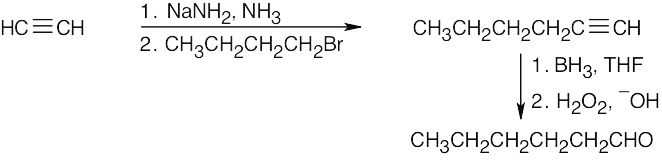

| 9.6 | Remember that hydroboration yields aldehydes from terminal alkynes and ketones from internal alkynes. | |

| (a) |  |

|

| (b) |  |

|

| 9.7 | (a) |  |

| (b) |

The desired ketone can be prepared only as part of a product mixture. |

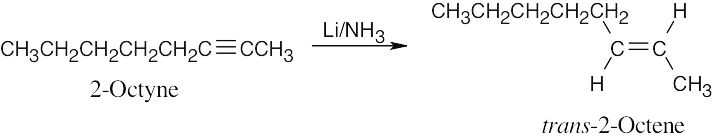

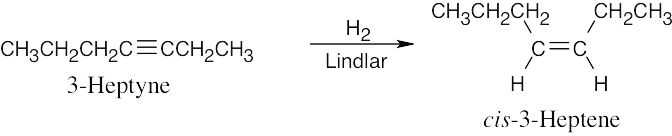

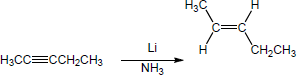

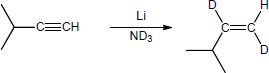

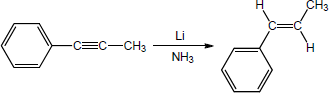

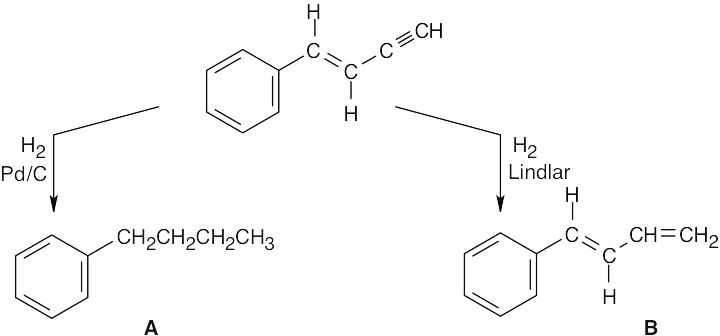

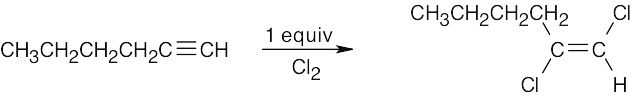

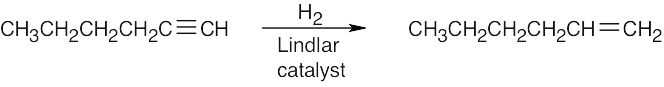

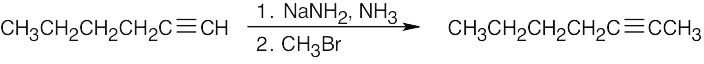

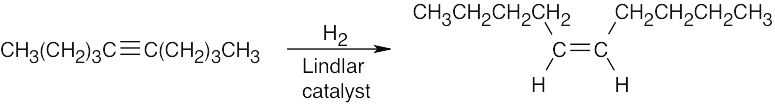

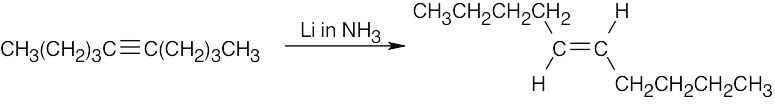

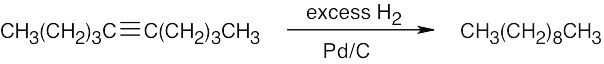

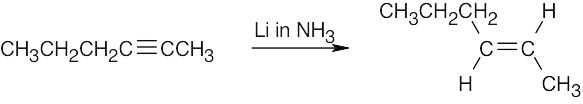

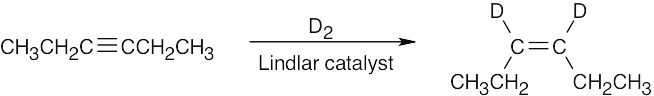

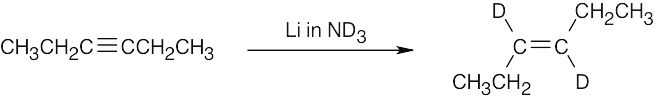

| 9.8 | The correct reducing reagent gives a double bond with the desired geometry. | |

| (a) |  |

|

| (b) |  |

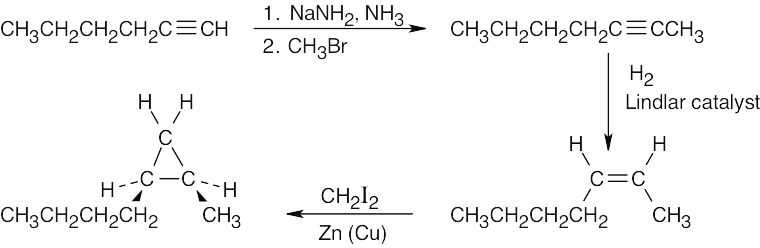

|

| (c) |  |

|

| 9.9 | A base that is strong enough to deprotonate acetone must be the conjugate base of an acid weaker than acetone. In this problem, only Na+ –C≡CH is a base strong enough to deprotonate acetone. |

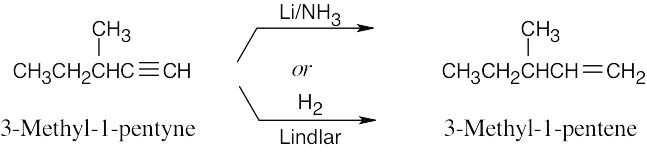

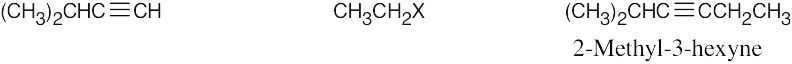

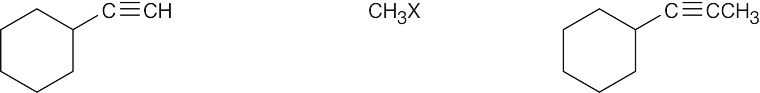

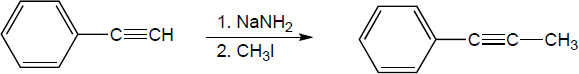

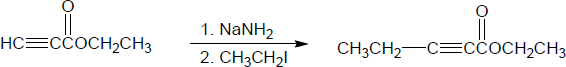

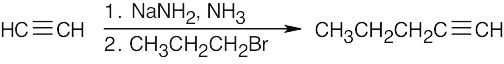

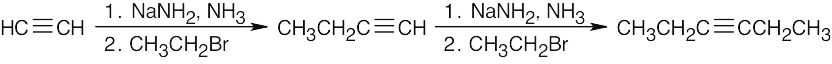

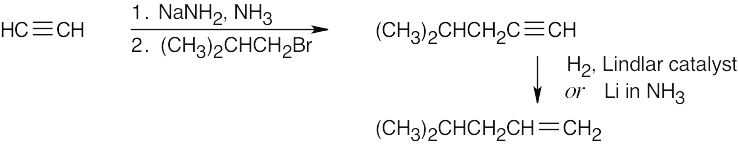

| 9.10 | Remember that the alkyne must be a terminal alkyne and the halide must be primary. More than one combination of terminal alkyne and halide may be possible. | |

| Alkyne R’X (X=Br or I) Product | ||

| (a) |  |

|

| (b) |  |

|

| (c) |

Products (b) and (c) can be synthesized by only one route because only primary halides can be used for acetylide alkylations. |

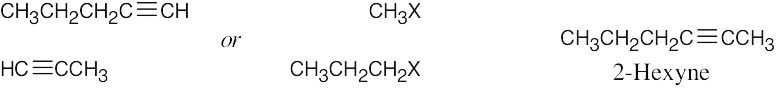

|

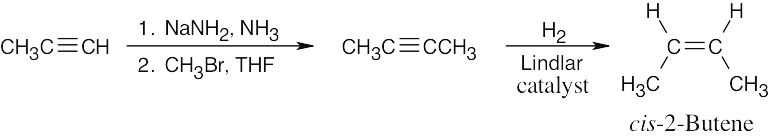

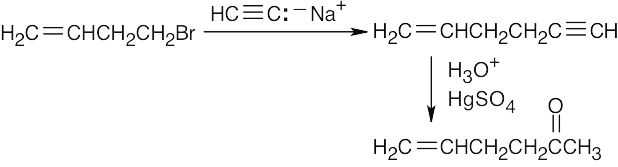

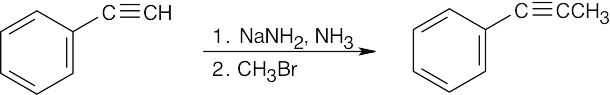

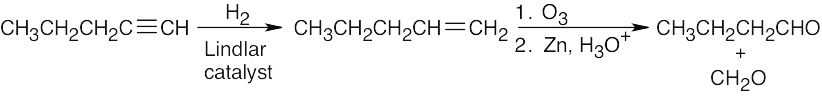

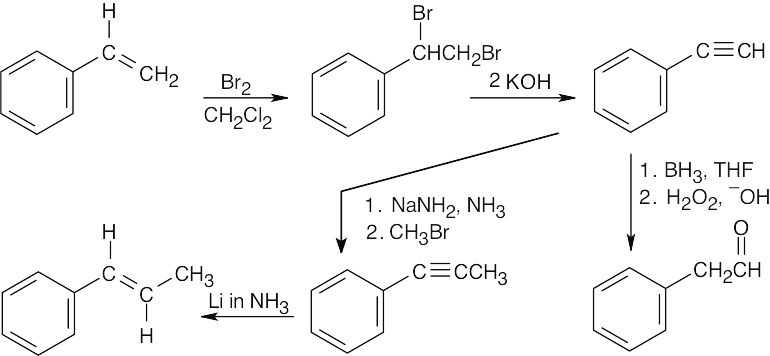

| 9.11 | The cis double bond can be formed by hydrogenation of an alkyne, which can be synthesized by an alkylation reaction of a terminal alkyne.

|

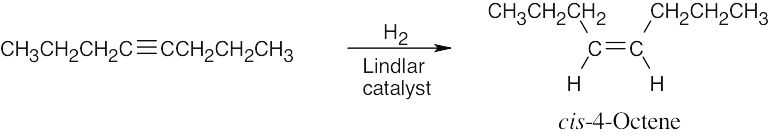

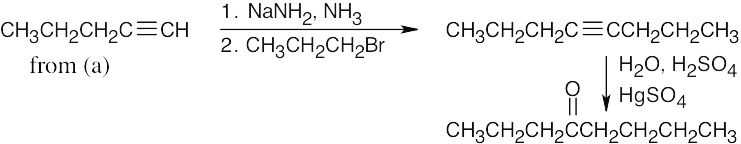

| 9.12 | The starting material is CH3CH2CH2C≡CCH2CH2CH3. Look at the functional groups in the target molecule and work backward to 4-octyne. | |

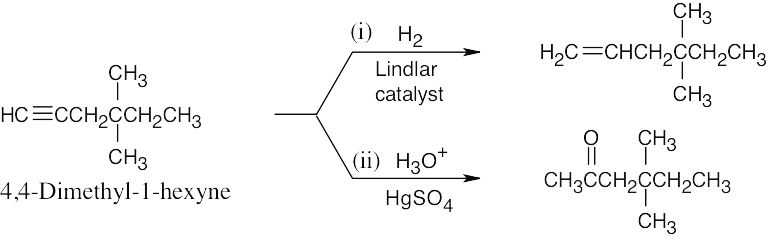

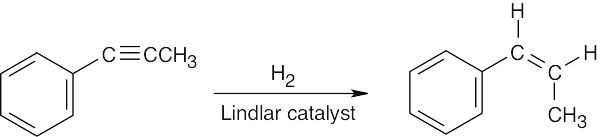

| (a) | To reduce a triple bond to a double bond with cis stereochemistry use H2 with Lindlar catalyst.

|

|

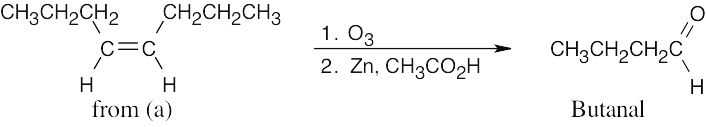

| (b) | An aldehyde is the product of double-bond cleavage of an alkene with O3. The starting material can be either cis-4-octene or trans-4-octene.

|

|

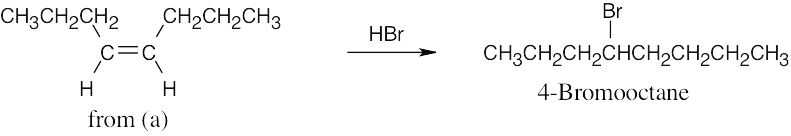

| (c) | Addition of HBr to cis-4-octene [part (a)] yields 4-bromooctane.

Alternatively, lithium/ammonia reduction of 4-octyne, followed by addition of HBr, gives 4-bromooctane. |

|

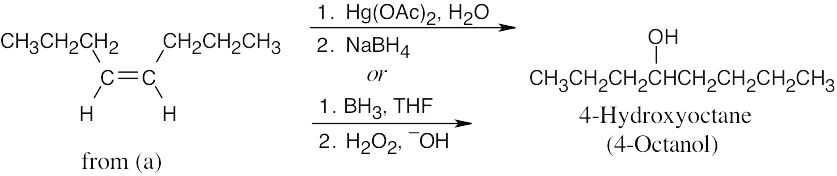

| (d) | Hydration or hydroboration/oxidation of cis-4-octene [part (a)] yields 4-hydroxyoctane (4-octanol).

|

|

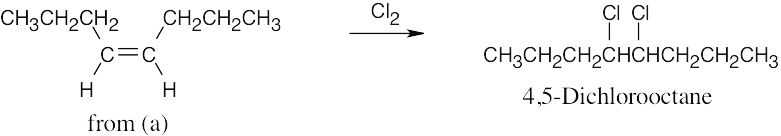

| (e) | Addition of Cl2 to 4-octene [part (a)] yields 4,5-dichlorooctane.

|

|

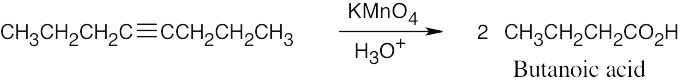

| (f) | KMnO4 cleaves 4-octyne into two four-carbon fragments.

|

|

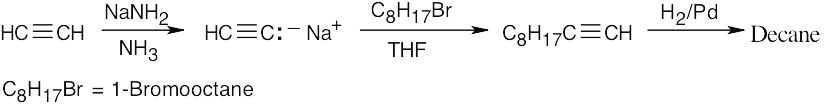

| 9.13 | The following syntheses are explained in detail in order to illustrate retrosynthetic logic – the system of planning syntheses by working backwards. | ||

| (a) | 1. | An immediate precursor to CH3CH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH2CH3 might be an alkene or alkyne. Try C8H17C≡CH, which can be reduced to decane by H2/Pd. | |

| 2. | The alkyne C8H17C≡CH can be formed by alkylation of HC≡C:– Na+ by C8H17Br, 1-bromooctane. | ||

| 3. | HC≡C:– Na+ can be formed by treatment of HC≡CH with NaNH2, NH3. | ||

|

|||

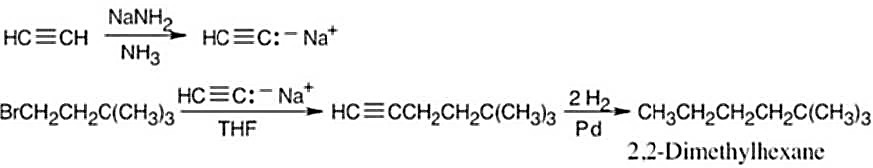

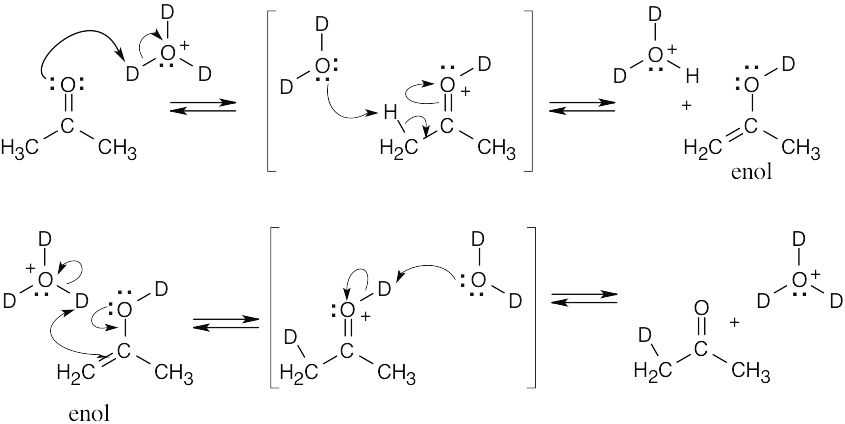

| (b) | 1. | An immediate precursor to CH3CH2CH2CH2C(CH3)3 might be HC≡CCH2CH2C(CH3)3, which, when hydrogenated, yields 2,2-dimethylhexane. | |

| 2. | HC≡CCH2CH2C(CH3)3 can be formed by alkylation of HC≡C:– Na+ (from a.) with BrCH2CH2C(CH3)3. | ||

|

|||

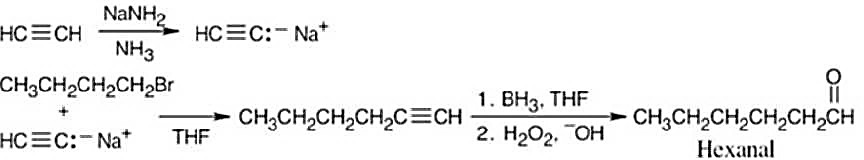

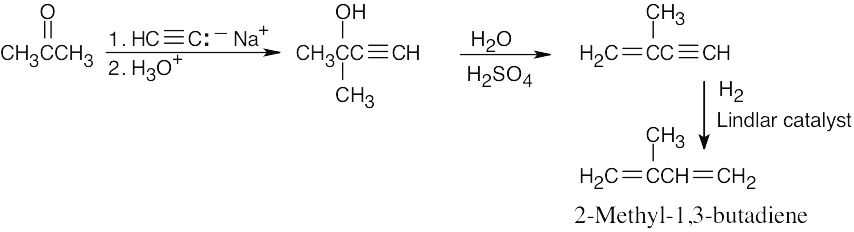

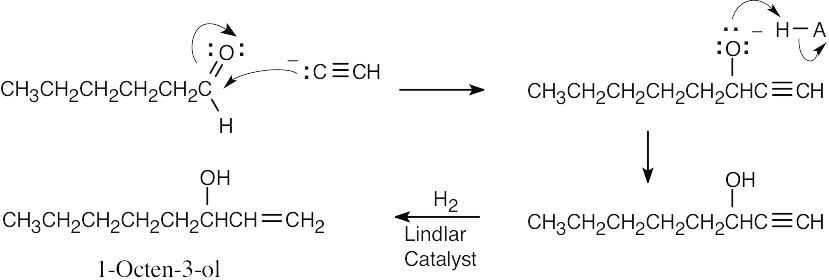

| (c) | 1. | CH3CH2CH2CH2CH2CHO can be made by treating CH3CH2CH2CH2C≡CH with borane, followed by H2O2. | |

| 2. | CH3CH2CH2CH2C≡CH can be synthesized from CH3CH2CH2CH2Br and HC≡C:– Na+. | ||

|

|||

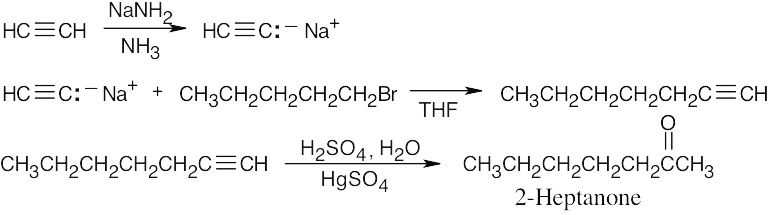

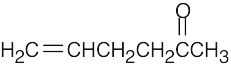

| (d) | 1. | The desired ketone can be formed by mercuric-ion-catalyzed hydration of 1-heptyne. | |

| 2. | 1-Heptyne can be synthesized by an alkylation of sodium acetylide by 1-bromopentane. | ||

|

|||

Additional Problems

Visualizing Chemistry

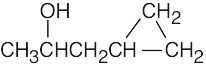

| 9.14 | (a) |  |

| (b) |  |

| 9.15 | (a) |

An aldehyde is formed by reacting a terminal alkyne with borane, followed by oxidation. |

| (b) |  |

| 9.16 | First, draw the structure of each target compound. Then, analyze the structures for a synthetic route. | |

| (a) |  |

|

| (b) |  |

|

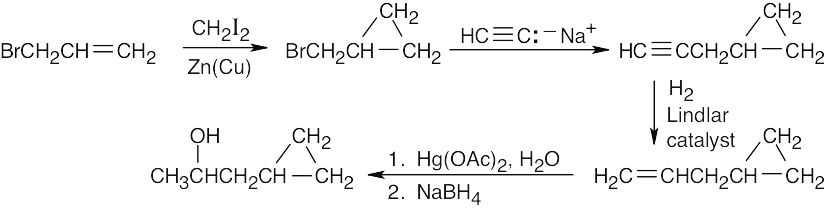

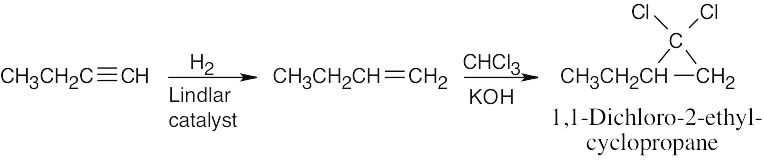

| (a) | The left side and the right side might have double bonds as immediate precursors; the right side may result from a Simmons-Smith carbenoid addition to an alkene, and the left side may result from hydration of an alkene. Let’s start with 3-bromo-1-propene.

|

|

| (b) | The right side can result from Hg-catalyzed addition of H2O to a terminal alkyne.

|

|

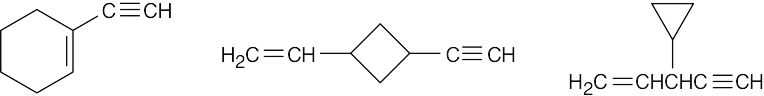

| 9.17 | It’s not possible to form a small ring containing a triple bond because the angle strain that would result from bending the bonds of an sp-hybridized carbon to form a small ring is too great. |

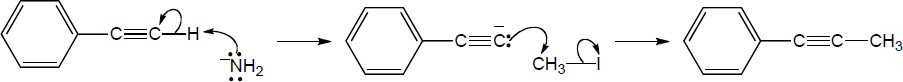

Mechanism Problems

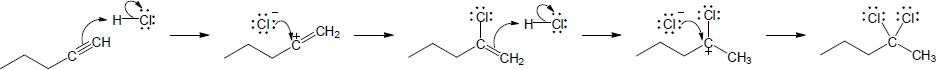

| 9.18 | (a) |

Mechanism:

|

| (b) |

Mechanism:

|

|

| (c) |

Mechanism:

|

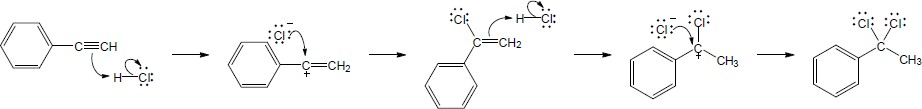

| 9.19 | Assuming that strong acids add to akynes in the same manner that they add to alkenes, propose a mechanism for each reaction below. | |

| (a) |

Mechanism:

|

|

| (b) |

Mechanism:

|

|

| (c) |

Mechanism:

|

|

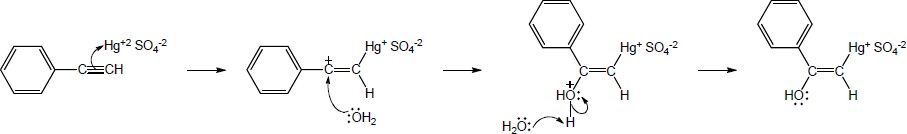

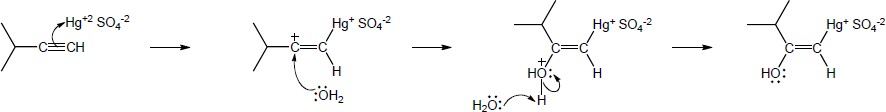

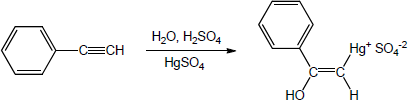

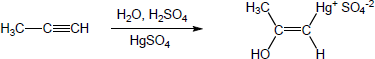

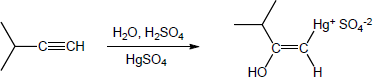

| 9.20 | The mercury catalyzed hydration of alkynes involves the formation of an organomercury enol intermediate. Provide the electron pushing mechanism to show how each intermediate below is formed. | |

| (a) |

Mechanism:

|

|

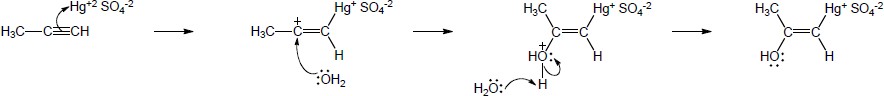

| (b) |

Mechanism:

|

|

| (c) |

Mechanism:

|

|

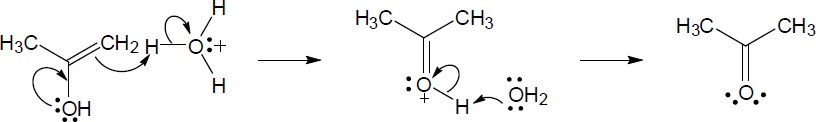

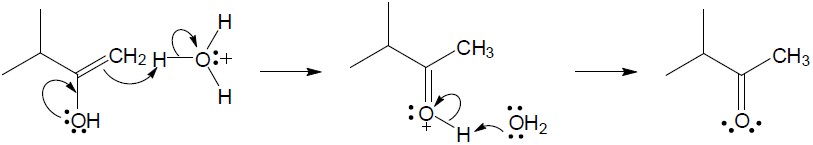

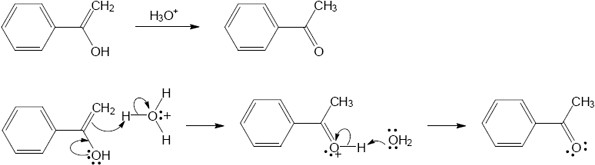

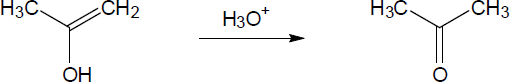

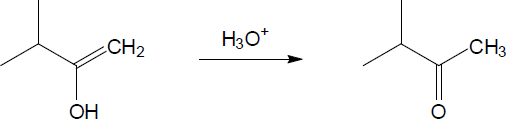

| 9.21 | The final step in the hydration of an alkyne under acidic conditions is the tautomerism of an enol intermediate to the corresponding ketone. The mechanism involves a protonation followed by a deprotonation. Show the mechanism of each tautomerism below. | |

| (a) |  |

|

| (b) |

Mechanism:

|

|

| (c) |

Mechanism:

|

|

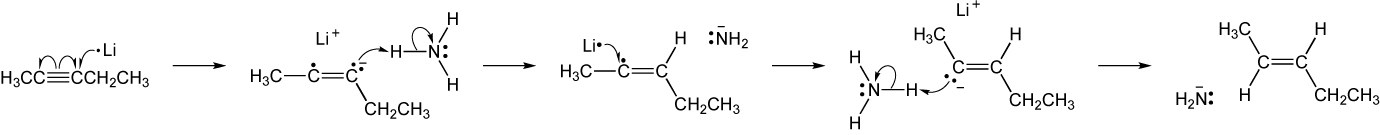

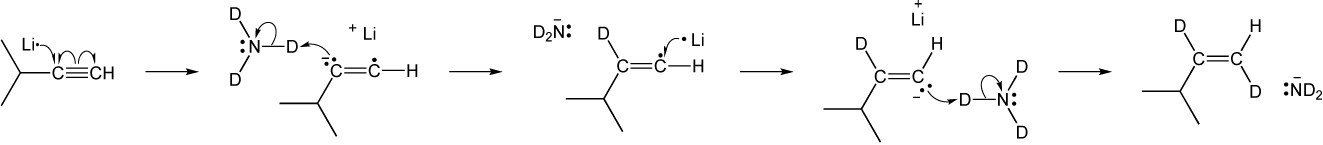

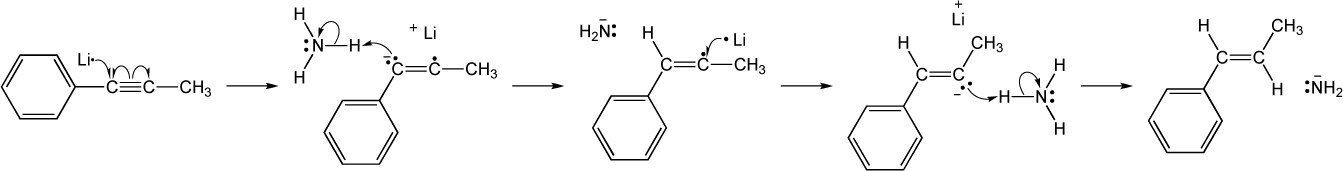

| 9.22 | Predict the product(s) and show the complete electron pushing mechanism for each dissolving metal reduction below. | |

| (a) |

Mechanism:

|

|

| (b) |

Mechanism:

|

|

| (c) |

Mechanism:

|

|

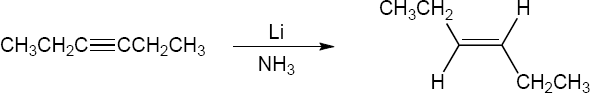

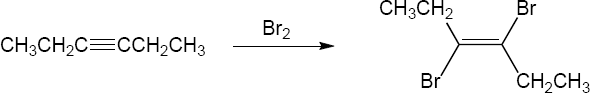

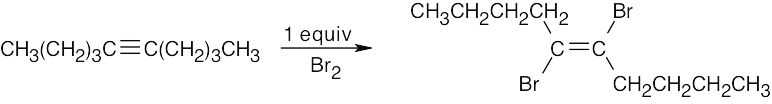

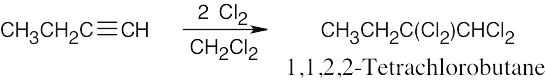

| 9.23 | Identify the mechanisms for the reactions below as being either polar, radical or both. | |

| (a) | Both. The addition of single electrons is a radical process, while adding protons is polar.

|

|

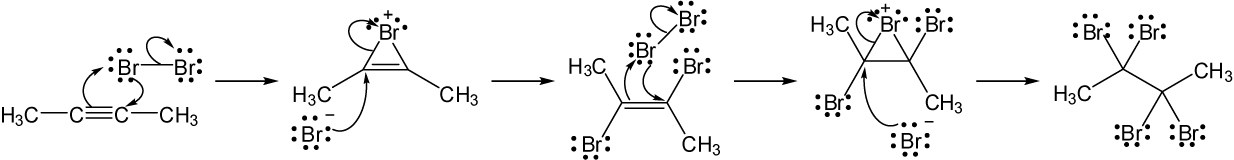

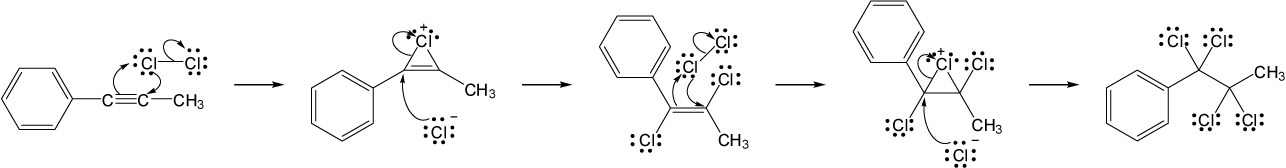

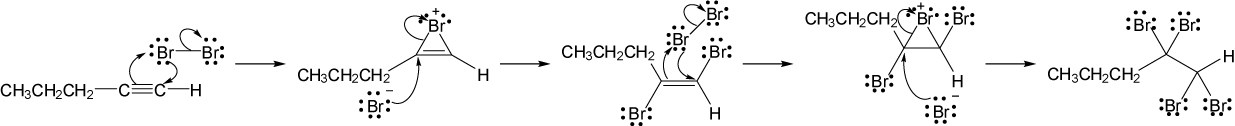

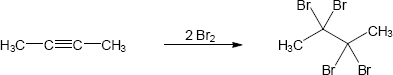

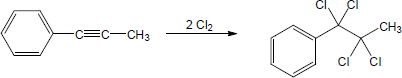

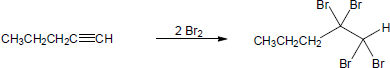

| (b) | Halogenation is a polar reaction.

|

|

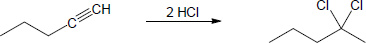

| (c) | Hydrohalogenation is a polar reaction.

|

|

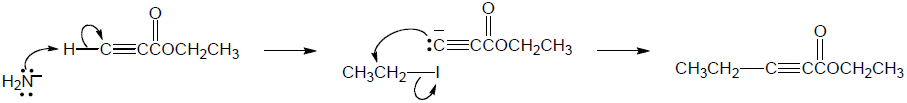

| 9.24 | Predict the product and provide the complete electron pushing mechanism for the two-step synthetic processes below. | |

| (a) |

Mechanism:

|

|

| (b) |

Mechanism:

|

|

| (c) |

Mechanism:

|

|

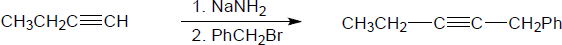

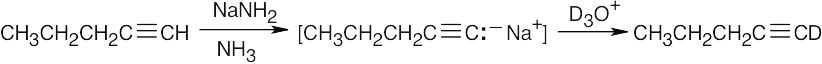

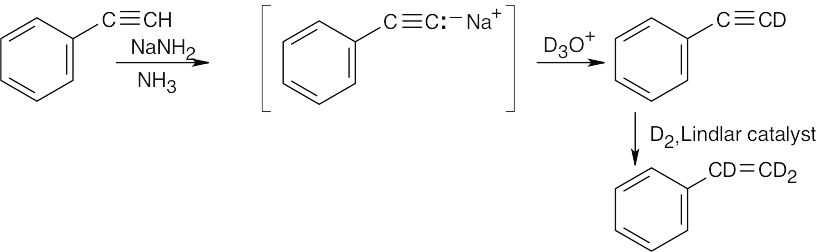

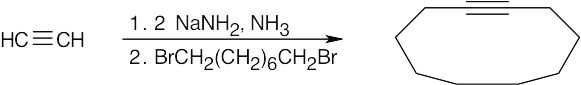

| 9.25 |

Repeating this process five more times replaces all hydrogen atoms with deuterium atoms. The first line represents the mechanism for acid-catalyzed tautomerization of a ketone. |

Naming Alkynes

| 9.26 | (a) |  |

| (b) |  |

|

| (c) |  |

|

| (d) |  |

|

| (e) |  |

|

| (f) |  |

| 9.27 | (a) |  |

| (b) |  |

|

| (c) |  |

|

| (d) |  |

|

| (e) |  |

|

| (f) |  |

|

| (g) |  |

|

| (h) |  |

| 9.28 | (a) | CH3CH=CHC≡CC≡CCH=CHCH=CHCH=CH2.

1,3,5,11-Tridecatetraen-7,9-diyne Using E–Z notation: (3E,5E,11E)-1,3,5,11-Tridecatetraen-7,9-diyne The parent alkane of this hydrocarbon is tridecane. |

| (b) | CH3C≡CC≡CC≡CC≡CC≡CCH=CH2. 1-Tridecen-3,5,7,9,11-pentayne This hydrocarbon also belongs to the tridecane family. |

Reactions of Alkynes

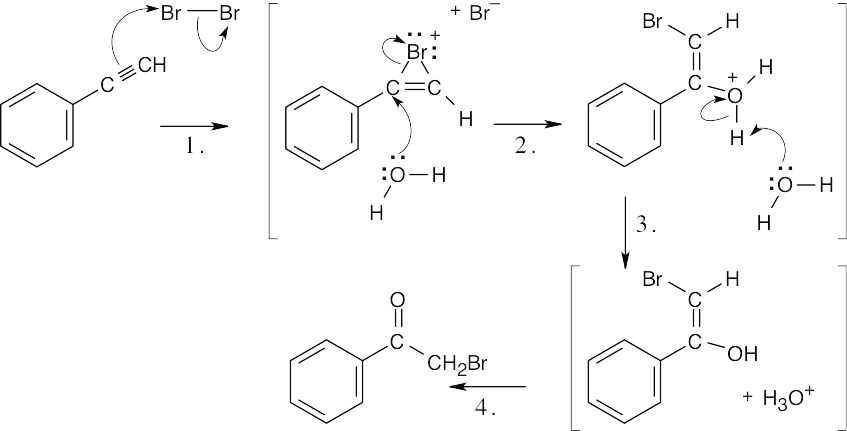

| 9.29 | This reaction mechanism is similar to the mechanism of halohydrin formation. | |

|

||

| Step 1: | Attack of π electrons on Br2. | |

| Step 2: | Opening of cyclic cation by H2O. | |

| Step 3: | Deprotonation. | |

| Step 4: | Step 4: Tautomerization (for mechanism, see Problem 9.48 and Section 9.4). | |

| 9.30 |  |

| 9.31 | (a) |  |

| (b) |  |

|

| (c) |  |

|

| (d) |  |

|

| (e) |  |

|

| (f) |  |

| 9.32 | (a) |  |

| (b) |  |

|

| (c) |  |

|

| (d) |  |

|

| (e) |  |

|

| (f) |  |

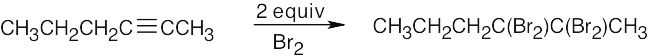

| 9.33 | Mixtures of products are sometimes formed since the alkynes are unsymmetrical. | |

| (a) |  |

|

| (b) |  |

|

| (c) |  |

|

| (d) |  |

|

| (e) |  |

|

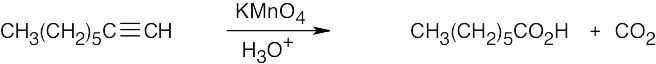

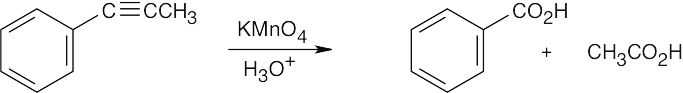

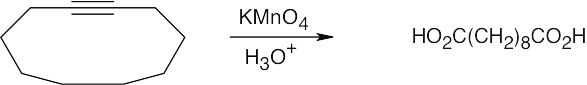

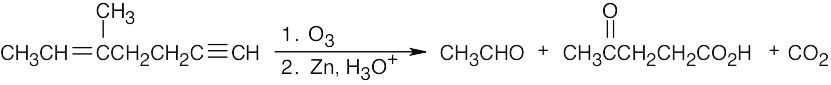

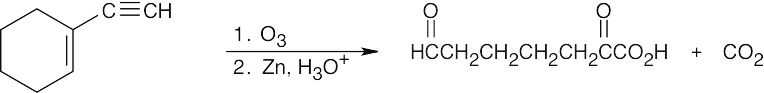

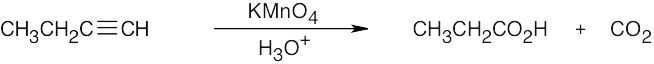

| 9.34 | Both KMnO4 and O3 oxidation of alkynes yield carboxylic acids; terminal alkynes give CO2 also. In (a), (b), and (c), the observed products can also be formed by KMnO4 oxidation of the corresponding alkenes. | |

| (a) |  |

|

| (b) |  |

|

| (c) |

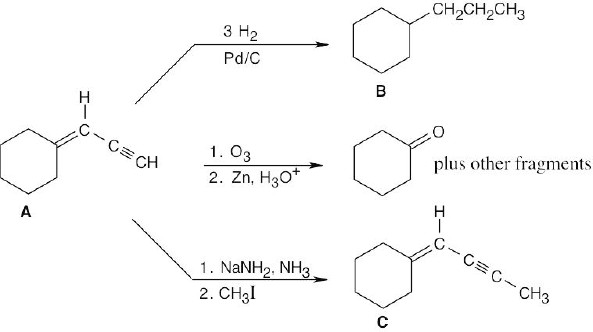

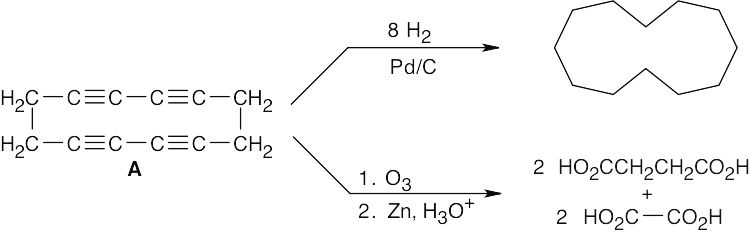

Since only one cleavage product is formed, the parent hydrocarbon must have contained a triple bond as part of a ring. |

|

| (d) |

Notice that the products of this ozonolysis contain aldehyde and ketone functional groups, as well as a carboxylic acid and CO2. The parent hydrocarbon must thus contain a double and a triple bond. |

|

| (e) |  |

|

| 9.35 |  |

Organic Synthesis

| 9.36 |

|

| 9.37 | (a) |  |

| (b) |  |

|

| (c) |  |

|

| (d) |  |

|

| (e) |  |

|

| (f) |  |

| 9.38 | (a) |  |

| (b) |  |

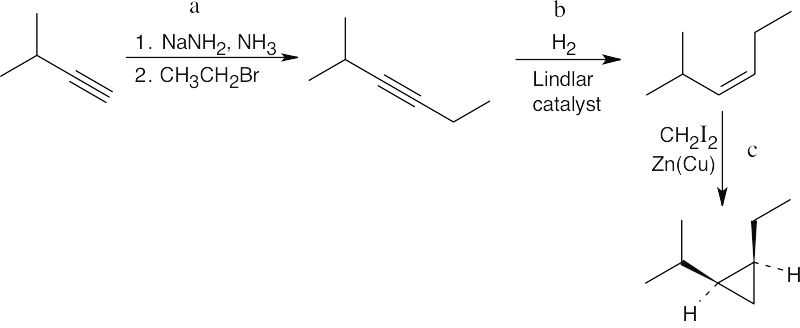

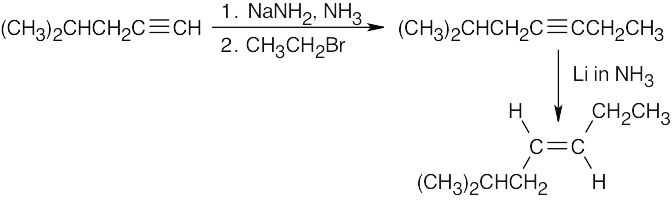

| 9.39 | The product contains a cis-disubstituted cyclopropane ring, which can be formed from a Simmons–Smith reaction of CH2I2 with a cis alkene. The alkene with a cis bond can be produced from an alkyne by hydrogenation using a Lindlar catalyst. The needed alkyne can be formed from the starting material shown by an alkylation using bromomethane.

|

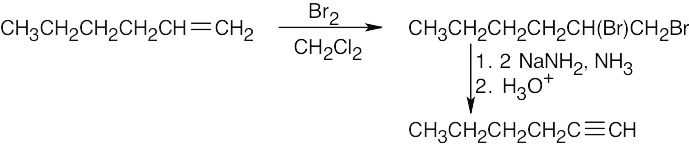

| 9.40 |

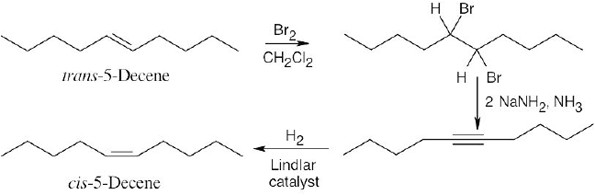

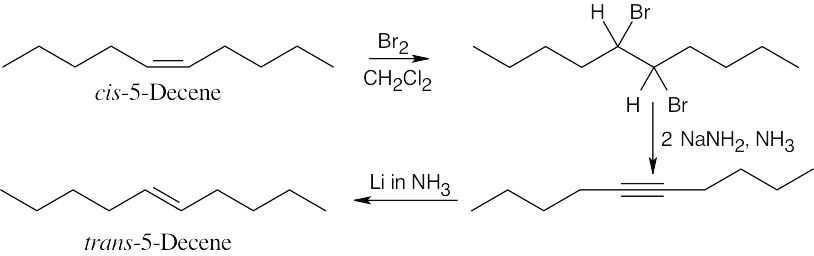

The trans double bond in the second target molecule is a product of reduction of a triple bond with Li in NH3. The alkyne was formed by an alkylation of a terminal alkyne with bromomethane. The terminal alkyne was synthesized from the starting alkene by bromination, followed by dehydrohalogenation. |

| 9.41 | (a) |  |

| (b) |  |

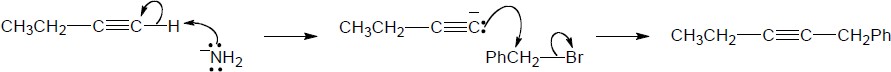

| 9.42 | In all of these problems, an acetylide ion (or an anion of a terminal alkyne) is alkylated by a haloalkane. | |

| (a) |  |

|

| (b) |  |

|

| (c) |  |

|

| (d) |

Hydroboration/oxidation can also be used to form the ketone from 4-octyne. |

|

| (e) |  |

|

| 9.43 | (a) |  |

| (b) |  |

|

| (c) |  |

|

| (d) |  |

| 9.44 |

A dihalide is used to form the ring. |

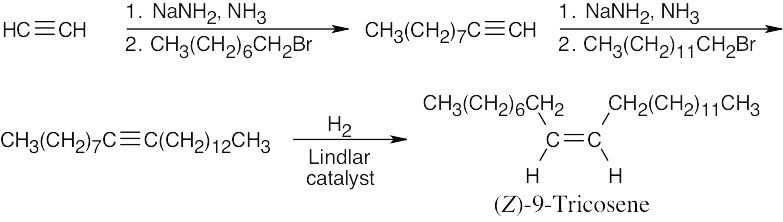

| 9.45 | Muscalure is a C23 alkene. The only functional group present is the double bond between C9 and C10. Since our synthesis begins with acetylene, we can assume that the double bond can be produced by hydrogenation of a triple bond.

|

General Problems

| 9.46 | (a) | An acyclic alkane with eight carbons has the formula C8H18. C8H10 has eight fewer hydrogens, or four fewer pairs of hydrogens, than C8H18. Thus, C8H10 contains four degrees of unsaturation (rings/double bonds/triple bonds). |

| (b) | Because only one equivalent of H2 is absorbed over the Lindlar catalyst, one triple bond is present. | |

| (c) | Three equivalents of H2 are absorbed when reduction is done over a palladium catalyst; two of them hydrogenate the triple bond already found to be present. Therefore, one double bond must also be present. | |

| (d) | C8H10 must therefore contain one ring. | |

| (e) | Many structures are possible.

|

| 9.47 |  |

| 9.48 |  |

| 9.49 | (a) |  |

| (b) |  |

| 9.50 |  |

| 9.51 |  |

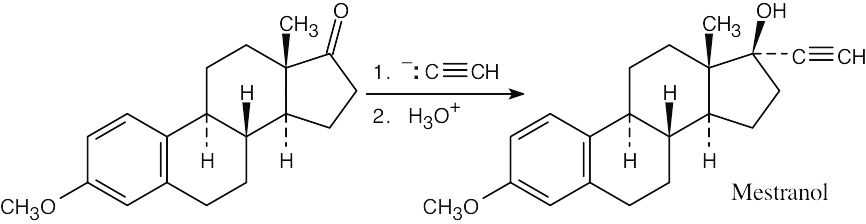

| 9.52 |

The addition of acetylide occurs by the same route as shown in Problem 9.41. |

| 9.53 | (1) | Erythrogenic acid contains six degrees of unsaturation (see Section 7.2 for the method of calculating unsaturation equivalents for compounds containing elements other than C and H). |

| (2) | One of these double bonds is contained in the carboxylic acid functional group –CO2H; thus, five other degrees of unsaturation are present. | |

| (3) | Because five equivalents of H2 are absorbed on catalytic hydrogenation, erythrogenic acid contains no rings. | |

| (4) | The presence of both aldehyde and carboxylic acid products of ozonolysis indicates that both double and triple bonds are present in erythrogenic acid. | |

| (5) |

Only two ozonolysis products contain aldehyde functional groups; these fragments must have been double-bonded to each other in erythrogenic acid. H2C=CH(CH2)4C≡ |

|

| (6) |

The other ozonolysis products result from cleavage of triple bonds. However, not enough information is available to tell in which order the fragments were attached. The two possible structures are: A H2C=CH(CH2)4C≡C–C≡C(CH2)7CO2H B H2C=CH(CH2)4C≡C(CH2)7C≡CCO2H One method of distinguishing between the two possible structures is to treat erythrogenic acid with two equivalents of H2, using a Lindlar catalyst. The resulting trialkene can then be ozonized. The fragment that originally contained the carboxylic acid can then be identified. (A is the structure of erythrogenic acid.) |

| 9.54 |  |

| 9.55 |

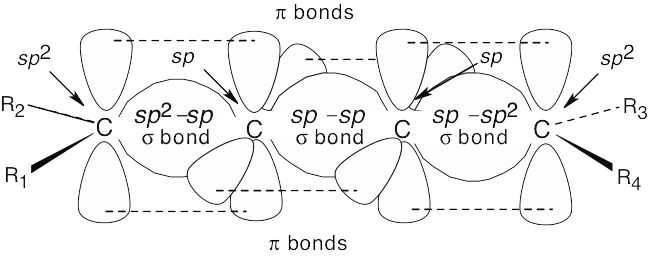

This simplest cumulene is pictured above. The carbons at the end of the cumulated double bonds are sp2-hybridized and form one π bond to the “interior” carbons. The interior carbons are sp-hybridized; each carbon forms two π bonds – one to an “exterior” carbon and one to the other interior carbon. If you build a model of this cumulene, you can see that the substituents all lie in the same plane. This cumulene can thus exhibit cis–trans isomerism, just as simple alkenes can. In general, the substituents of any compound with an odd number of adjacent double bonds lie in a plane; these compounds can exhibit cis–trans isomerism. |

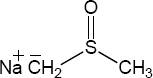

| 9.56 | In order for a base to be strong enough to deprotonate an acid, the conjugate acid of the base must be a weaker acid (have a higher pKa) than the acid being deprotonated. The pKa of 1-butyne is 25. | |

| (a) | The pKa of H2O (the conjugate acid of hydroxide) is 15. Because water is a stronger acid than 1-butyne, hydroxide will not deprotonate 1-butyne.

KOH |

|

| (b) | The pKa of dimethylsulfoxide (the conjugate acid of methylsulfinylmethylide ion, also called dimyslate ion) is 35. Because dimethylsulfoxide is a weaker acid than 1-butyne, methylsulfinylmethylide will deprotonate 1-butyne.

|

|

| (c) | The pKa of butane (the conjugate acid of n-butyl lithium) is approximately 60. Because butane is a weaker acid than 1-butyne, n-butyl lithium will deprotonate 1- butyne.

CH3CH2CH2CH2Li |

|

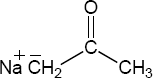

| (d) | The pKa of acetone (the conjugate acid of acetone enolate) is 19. Because acetone is a stronger acid than 1-butyne, acetone enolate will not deprotonate 1-butyne.

|

|

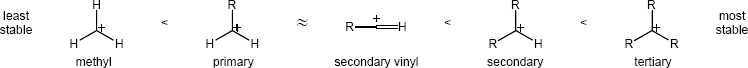

| 9.57 |

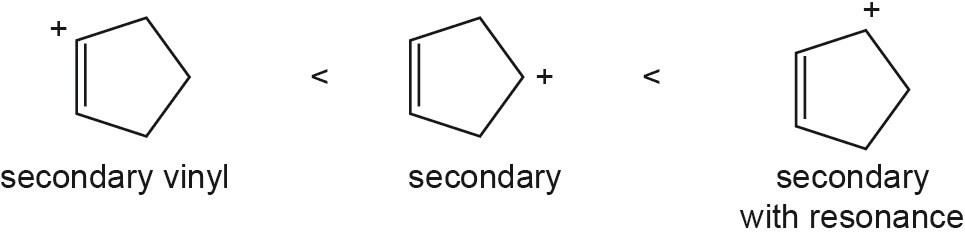

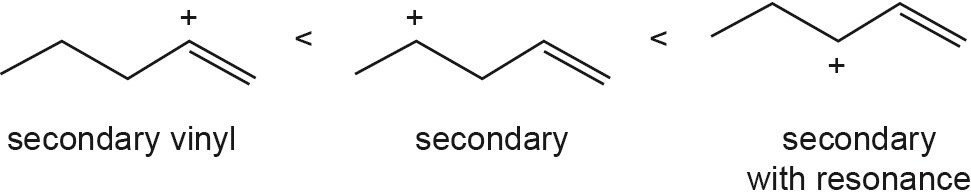

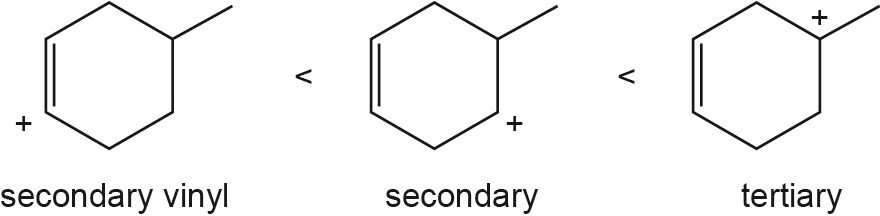

The overall trend for carbocation stability is shown below. Recall that resonance adds additional stability to carbocations.

|

|

| (a) |  |

|

| (b) |  |

|

| (c) |  |

|

This file is copyright 2023, Rice University. All Rights Reserved.