10 Format and Style

Format

In chapter 7 we looked at a couple of short scenes, one from Legally Blonde and one from Barbie. Let’s look at the Barbie scene again and use it to begin our analysis of format. These example pages are set apart from the rest of the text so they are easy to recognize. Because of this, you may not be able to identify the font, but screenplays are written in Courier 12 point font. (Please note that, like in a treatment, the first time we see a character, their name is in all caps, but that is just for the first instance we see them.)

The scene starts with INT. VENICE CENTRAL BOOKING – DAY. This is known as a slugline. Sluglines give the location and if it is day or night. Screenplay scenes start with a slugline to tell us where the scene takes place and when it takes place. Most sluglines end with DAY or NIGHT. That’s it. We can sometimes use LATER to show that this happens a short time after the previous scene. We can also use HOURS LATER or MINUTES LATER. However, most of the time you should use DAY or NIGHT. Yes, if it is important to the plot that the scene takes place at DUSK or at DAWN you can use those, but that is rare.

Locations are not just INT. HOUSE either. Treat different rooms as different locations. INT. SARAH’S BEDROOM – DAY would be for her bedroom. If we go to her kitchen it becomes INT. SARAH’S KITCHEN – DAY. See? Each room in a house becomes a location. The Barbie scene doesn’t take place INT. POLICE STATION. It is INT. VENICE CENTRAL BOOKING. That is a specific part of the police station.

The next part of the scene is this: “Barbie Margot and Ken Ryan Gosling’s mug shots. Then they are being finger printed. Over and over again because the cops can’t find any prints. The cops drool over Barbie Margot…” This part is called action description. Here is where we describe what the characters are doing and describe the setting. Action description is in present tense. Always.

This is really, really important, so I am going to write this in all caps: SCREENPLAY ACTION DESCRIPTIONS ARE SHORT! Notice how little is described in this scene from Barbie. A screenplay is not a novel or a short story.

There are production designers, costume designers, directors, cinematographers, etc. working on a movie. Some, if not all of them, will have input on how the film looks. From your basic descriptions, they will create costumes and setting, etc. Yes, these decisions are based on the screenplay, but the screenplay is just giving them an idea, a blueprint, and their artistic sensibilities and creativity will bring it to fruition.

Look at the description from the scene after Barbie and Ken buy new clothes. “Ken Ryan Gosling exits wearing all denim with fringe and a cowboy hat, followed by Barbie Margot, who wears a pink cowgirl outfit. ALL the security lights and bells go, but they are oblivious.” That’s all that is needed. It just says “a pink cowgirl outfit.” Again, as the writer we are giving the basics to inspire other people working on the film.

After the action description, we have a dialogue tag that gives the name of the character speaking and then we get their dialogue. Notice how the dialogue tag is offset from the slugline and the action description. It is not at the same margin. Likewise, the dialogue is offset from the tag, at a different margin. When Ken says he loves fringe, there is a parenthetical to indicate he is admiring himself in the mirror. A parenthetical is a quick note about the dialogue being said. Remember when we talked about dialogue before and how tone could change the meaning of a single word? In a parenthetical is where you can put that tone. In our previous example, we could use a parenthetical (sarcastic) for their saying “great.” Then we know they are not being sincere.

Those are the building blocks of screenplay format. There are other aspects, but those building blocks will take you a long way.

Remember the hypothetical script we used before? The one about the construction worker running for mayor against his father to save the family home? Let’s use a scene from that to illustrate some finer points of format.

Look at the sluglines. As we talked about above, each room in the house is its own location, so to speak, so it gets its own slugline. The foyer has a slugline. The living room has a slugline. The kitchen has a slugline.

Screenplay format came about in the studio system. It was a way for each department working on a film, from set designers to actors, to easily find what they need in the script to do their jobs. If you are a location scout working with a director and you get the script, you can fairly easily go through and find each location that will be needed.

Movies are huge logistical undertakings. They are rarely shot in order. Scenes in the middle of the movie may be shot first. Heck, the opening could be shot last. It depends on logistics. We could have a kitchen, living room, and foyer in three different houses and edit them together to appear to be one house. Regardless if it is all one house or not, most likely we are going to shoot all the scenes in the living room together. That way once the lighting, etc. is all set up, we can get all of those shots done before breaking the equipment down and moving on to, say, the kitchen. In the kitchen we will shoot all of those scenes.

The format evolved as a way to aid in the production of the movie, from pre-production through post production. Because of this, and because we shoot movies out of order, make sure you treat different rooms, like it is done here, as different locations.

Next, you will notice that the word SLAM is in all caps. Sounds in a screenplay are in all caps. Again, that goes back to the people working on the movie. Sound designers and engineers can easily spot specific sounds needed when they are in all caps. Other examples of this are a BLAST of thunder, a gunshot BANG, a bell RINGING.

Notice (O.S.) after Sue’s first dialogue tag? That indicates OFF SCREEN. O.S. means that a character is part of the scene, we hear them, but we don’t see them. In this scene, Sue is in another room so we hear what she says to Bill but we do not see her until he enters the living room.

Look at the action descriptions and how succinct they are. Bill drives a “beat up pickup” and that’s enough of a description for that. We don’t have to go into color and brand and where it looks beat up, etc. It’s a Victorian style house, a big one. That’s all we need to know about that exterior.

Inside, we see that it could be a really nice home, wainscoting, crown molding, etc. But it is also under repair. The state of disorder is described quickly. We do not have to pinpoint every aspect that has not been updated or repaired. We get it. Even better, part of it we get in action – the door not quite working properly so it slams shut.

Here’s another scene from our hypothetical movie.

In the kitchen, we use INSERT to highlight a photograph and a needlepoint. You need to remember this. In fact, write this down and put it next to your computer so you will always be reminded: try not to include camera directions in your screenplay. You are not the director. You are not shooting the movie. You should stay away from things like CLOSE-UP or WIDE SHOT or PAN or whatever.

I know, I know. You have read some screenplays and they include camera directions. Well, they may have been written by an established writer who can get away with that. Or, you have been reading the shooting script, which has already been rewritten for the filming of the movie so is different from the original script. Maybe you have been reading a script that the director wrote and thus, since they are directing it, includes how it will be shot. You, though, are just starting out and should stay away from camera directions.

However, we can put in something like INSERT to make sure people see this thing that a character is looking at. Say you want to show a text message on someone’s phone. There, you would use INSERT PHONE to show the text.

After we are done showing whatever it is we needed in the INSERT we go BACK TO SCENE. That is how we end the INSERT to let everyone know we are back to where we were.

Style

See how this scene doesn’t use the camera direction POV (POINT OF VIEW)? Rather than use a specific camera direction, the scene says “Bill notices.” That little description basically implies a POV shot without actually saying POV shot. That’s a stylistic choice, a way of creating visuals without explicitly using camera directions.

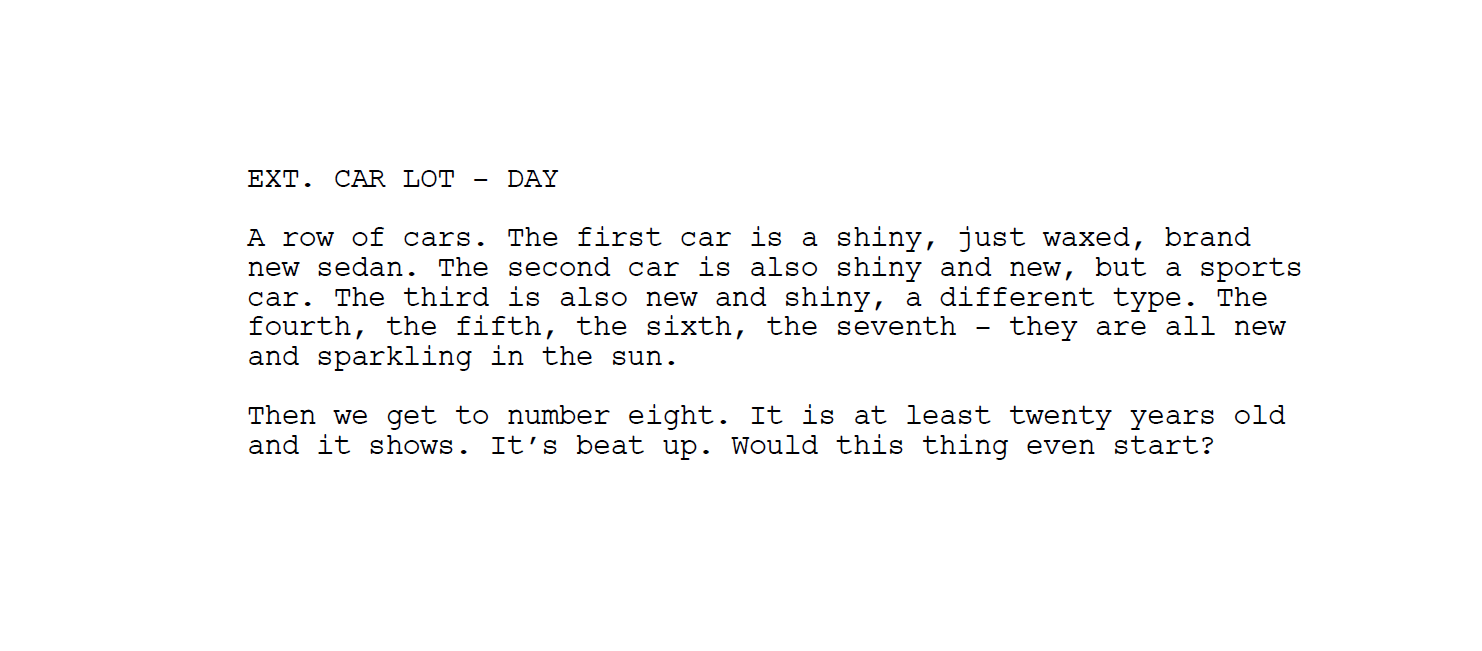

Say you are writing a scene and you visualize the camera panning over a row of cars. There is a point to panning because the last car is different than the others, but you want to reveal that more slowly than just having all the cars in one shot. Again, there are ways to do that without using a camera direction. We could write it this way:

We did not have to use a camera direction at all to convey the idea of panning across a row of cars. Further, it is written in a particular authorial voice, a style.

And you know what? A screenplay does have its own style. A screenwriter has a voice and a style just like a novelist or poet. Some screenplays read breezy and light. Other screenplays are heavier and more emotional. That is a stylistic choice the writer makes to try and match the plot of the movie. If you are writing a comedy, the screenplay should be funny.

Look at this particular action description: “Yeah, this place is falling apart, but it’s his damn place. How can the town…and boom! Bill is hit with an idea, an epiphany, the proverbial light bulb is glowing over his head.” I’m not saying this is brilliant writing but it does show how a screenwriter can have a particular style, and how that style can tell us a lot in a few words. This doesn’t describe the minutia of Bill’s mental state. However, it does show us Bill’s thought process and it does it in a way in the writer’s voice. No other writer would describe Bill’s epiphany in this way. This is a unique voice that the writer feels fits the script.

No, as the screenwriter you are not directing the movie and using camera directions. No, as the screenwriter you do not describe settings in great detail or write a long, beautiful passage to highlight a character’s inner life and thoughts, like a novelist or short story writer does. Yes, an emphatic YES, as a screenwriter you do have a unique voice and style. I think screenplays, like theatrical plays, are a form of literature. You should approach it that way. It is a different form of literature, but still literature.

Developing a voice and a style can take time. The more you write, the more you will realize your own voice.

In the previous chapter we discussed three common plot devices: flashbacks, montages, and voiceovers and, of course, these each have their own formats.

Flashbacks

There are a few different ways to do a flashback but the two most common are for short flashbacks and long flashbacks.

Let’s say you have a short flashback, just a quick flash to a memory. For that, you can put FLASHBACK in the slugline.

EXT. BILL’S PORCH – DAY (FLASHBACK)

Then a new slugline without the (FLASHBACK) means we are back in the present.

If you are doing a longer flashback, one that will cover a number of scenes, then establish you are doing the flashback.

BEGIN FLASHBACK

EXT. BILL’S PORCH – DAY

This way you can have a number of scenes in different locations and you don’t have to keep putting FLASHBACK in the slugline.

After the flashback you put:

END FLASHBACK

After END FLASHBACK, we know we are back in the present.

Montage

There are a few ways to do a montage but we will focus on one standard method.

Take the 1980s staple, the trying on clothes montage. In that one we can name the montage as trying on clothes since it is in one location.

We have already established that two characters are say in one of their bedrooms. So we can just do…

You can do something like that for a montage that covers several locations too.

In both of these examples, we basically give each action its own line. In the first, that means each outfit is its own line. In the second example, each exercise is its own line.

In both of these examples, we basically give each action its own line. In the first, that means each outfit is its own line. In the second example, each exercise is its own line.

Voiceover

Voiceover is formatted like off screen but instead of (O.S.) after the dialogue tag, it is (V.O.)

In this example, it is Bill’s interior thoughts. Voiceover is not coming from someone in the scene speaking. It is easy to confuse O.S. and V.O. but remember that voiceover is not someone speaking aloud in the scene. Rather, voiceover is a type of narration.

Software

There are bushels of screenwriting software you can purchase (and some free ones too). I am not endorsing a particular one, but, if you are serious about screenwriting, you should use screenwriting software. A good screenwriting program takes most, not all of it mind you, of the worry about formatting away. The best of these programs cover every format situation. If you are not sure about a particular format, they have a search function that allows you to find the specific formatting scenario you need and then adapt it to the situation you are writing. Software can spare you a lot of headaches.