7 Writing Scenes

All About Scenes

At this point, you might be wondering: “just when the heck do I get to actually write the screenplay?” We are not too far off from that. Keep in mind though that this structural work will help us greatly when writing. Knowing our outline helps us to determine what scenes we need. Knowing the character arc means we know the emotional state of our character at each point and thus have a good idea of how to write the character.

First off, let’s define a movie scene because scenes are the building blocks of movies (and thus the screenplay). A scene is a dramatic unit unfolding in a specific location over a specific time period.

Got it? Maybe not with that technical of a definition. Think of a scene as a dramatic point in one location (general location; it can be multiple rooms). I’m sure you have discussed favorite scenes before with friends. Some movie scenes have become cultural touchstones: Darth Vader revealing he is Luke’s father in Empire Strikes Back, or the diner scene in When Harry Met Sally, or the “I’m going to make him an offer he can’t refuse” scene in The Godfather. Each of those scenes have something dramatic happen in a specific location over a specific amount of time. We string scenes together to create our screenplay.

Once we have our outline, we can look at each step and break open the step to see what scenes we need to complete it.

Let’s work with a hypothetical step. Remember the logline we created? Here it is again:

When the current mayor marks his home for demolition, an average construction worker must run for mayor against the incumbent, his own father, to save the house his great grandfather built.

The Establishment step for our logline might look like this:

Establishment: We need to show our main character is a construction worker. He doesn’t build fancy buildings or hundred-million dollar houses. He’s a typical construction worker. But he is good at his job. We have to show the house he lives in and how this house is important to him. We need to show that he’s not into politics even though his father is the mayor. We need to show this is not a major city, just a kind of regular town.

That’s the Establishment step for our screenplay. Looking at it closely, we can determine specific scenes needed for this story.

Scene 1: Show him working at a site. He’s helping frame a house. He’s doing good work. The foreman or supervisor compliments him. So we reveal elements of his character, how he works, how he gets along with coworkers, etc.

Scene 2: He arrives home. We get a sense of the town, a bit, here. We see this is an older home. We introduce his wife and they have a couple of kids. We see he’s doing some renovations himself on the house. It is kind of an ongoing project for him. His restoration is all about keeping his great grandfather’s original intent. We see that this is his normal.

Scene 3: We get a scene with his father to set up that relationship. We reveal the father is the mayor and he mentions some city deals. He also mentions the house and how the construction worker should really sell it because it is old.

We can do this for each step of our outline and we know our construction worker’s emotional state at each step because we examined his arc.

Once you have a general outline, like above for Legally Blonde, you can then write down the scenes you need under the steps.

Establishment

Scene 1:

Scene 2:

Another example: At the Fallout stage, you know you need to show how the World Being Turned Upside Down emotionally rocks your main character. You have to have scenes to reveal that low. Those scenes need to be tailored to your character. How our construction worker responds to his World Being Turned Upside Down is not the same as how Elle responds to her World Being Turned Upside Down.

In our hypothetical story, it might look like this:

Fallout

Scene 1: It’s early in the morning, just after dawn. Our construction worker is pounding away on wainscoting in the living room. Tools are scattered about; he’s been at this already for a while. His wife and kids come downstairs. What the heck is he doing? Why is he making all of this noise so early? (Building is how he deals with frustration.)

Scene 2: He’s outside now working on a porch or something. His wife comes out. It’s after 10am. Is he not going to work? The foreman called and wanted to know where he is. Oh crap, he says. He forgot. But he never forgets to go to work. This shows that he is so distracted.

So on.

Break open each step and write down the scenes that will complete the step.

Writing Scenes

The great screenwriter (and novelist) William Goldman once said this about writing movie scenes: “Get in as late as possible and get out as soon as possible.” In essence, movie scenes are short. They have a point to make, make it, and then are over. We don’t need to dilly dally leading up to the point either. Get to the point and then go to the next scene. Obviously, there are various lengths of movie scenes. This doesn’t mean that every scene is only a few seconds. What it does mean is that we need to know what is important in that scene, make sure we show that, and then go on.

We are all savvy, sophisticated, intelligent movie viewers. Why? Because we have been watching movies and TV all of our lives. The language of movies is like a second language for us, one we are completely fluent in. People may not know all of the specific terms associated with movies, but they know their structure. No one is confused, for instance, by a closeup.

Here’s what I mean: Let’s say we are showing a character going to work. They are in a hurry.

Their keys are on the kitchen counter. They run into the kitchen; their spouse or partner is eating breakfast. They say they need to hurry to get to work and grab the keys.

Now, do we need to show them unlocking the car with the fob? Getting in, starting the car? Do we need to show them driving?

No, we don’t. We could go directly from their grabbing the keys to walking into an office. Viewers know they had to unlock the car, start it, drive, etc. They will fill in the blanks. That’s what I mean by viewers are savvy. We don’t have to show every detail because viewers fill in the gaps.

Now, maybe you need to show this person is a terrible driver. That is important later to the plot. In that case, yes, we need to include that detail. But unless something is crucial in those going-to-work scenes, we do not need to show them.

In writing a movie, we don’t have to write all the small talk and pleasantries that occur in regular life.

If at the end of a scene a character’s boss tells them to go talk to Alex, we don’t have to see them knock on Alex’s office door, say “hello,” mention the boss told them to talk, etc. The next scene can start in the middle of the conversation with Alex.

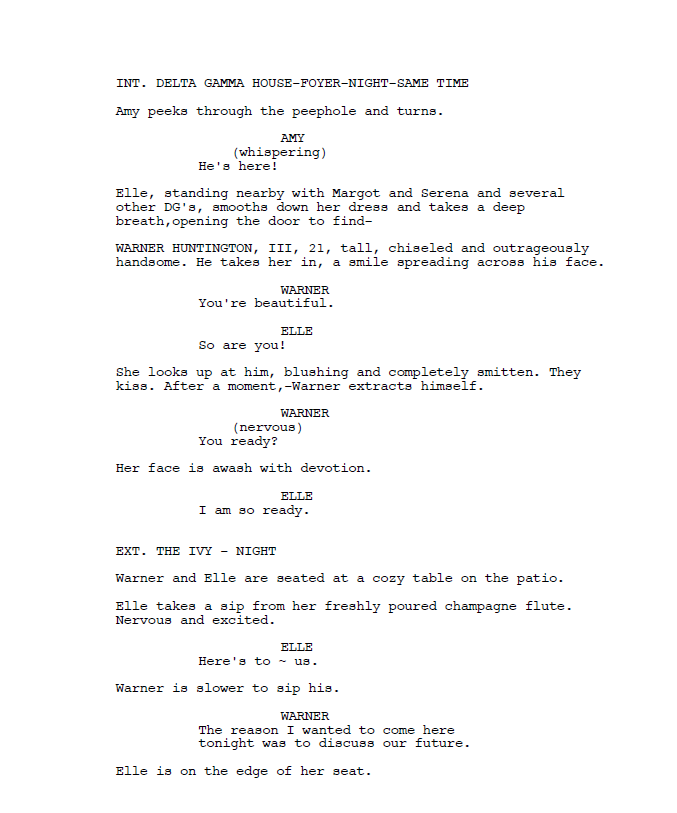

Let’s look at a quick example from Legally Blonde. This excerpt begins when Warner arrives at the sorority house to pick up Elle. She thinks this is the night he is going to propose.

If you are new to screenwriting, the format probably looks bizarre. You may even have some trouble following it. Don’t worry. We will cover format.

For right now, notice how it goes from Warner asking “are you ready” to the restaurant. They are already seated, sharing a toast. We didn’t have to see the drive over. We didn’t have to see them order drinks. Those things are not important. What is important is getting to the talk of their future.

Pleasantries are not needed in a screenplay. We know those things happen, but we don’t have to put those in the screenplay.

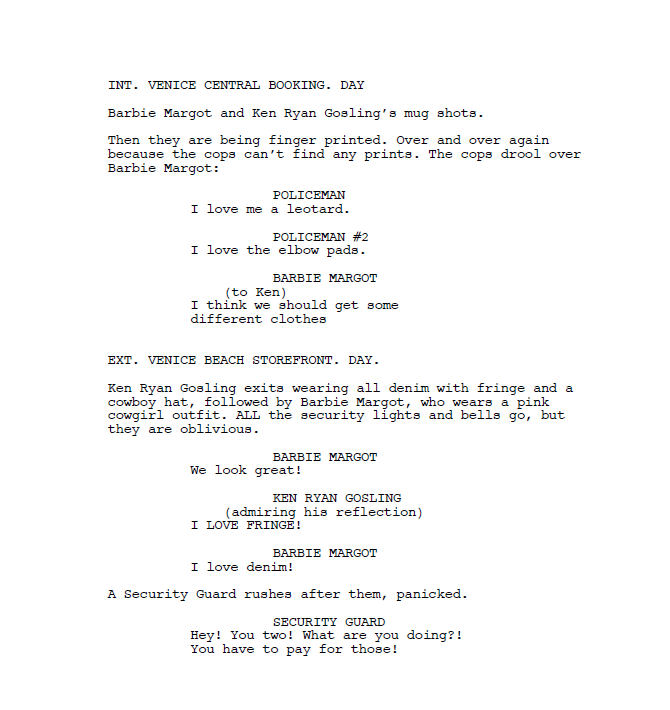

Here’s another example from Barbie.

We go directly from Barbie Margot saying they need new clothes, to Barbie Margot and Ken Ryan Gosling walking out of the store in new outfits. We did not have to see them going through racks of clothes searching for their size or trying clothes on. We know all of that happened, but it is not important, so we skip over it. Again, the audience fills in those blanks.

As you plan your scenes, keep the “get in late, get out early” in your mind. In fact, it should be in the forefront of your mind.

Visual Storytelling

Movies, obviously, are a visual medium. The screenplay exists on the page, but the goal is to make a movie, and that end product is something we watch and not read. (I do believe screenplays have literary value, but we will talk about that later.)

A screenplay employs visual storytelling. The axiom “show don’t tell” is a creative writing staple. It applies to screenwriting more than any other form of creative storytelling.

As you are constructing scenes, think about actions. The best way to engage your audience and to reveal character is through action. That doesn’t mean “action movie.” Small actions tell us a lot about someone. We learn about Elle’s kindness by her actions towards other people. We learn about her intelligence by her actions in the boutique when she will not let the sales person scam her.

We learn about Captain America’s physical abilities through action. How can we show he is more physically gifted than normal people? We show him running 13 miles in 30 minutes. We do not have him or another person tell us about his gifts. Just like we don’t have Elle or one of her friends tell us about her kindness. No, we see those things in what they do, their actions.

Actions are visual. Talking, by and large, is not visual. When you think about your main character’s internal conflicts, their fears, anxieties, etc., you need to think about ways to show those externally. The character describing their fears/anxieties is not as powerful as seeing those fears/anxieties.

To use an extreme example, how should you show a character has a crippling fear of heights? You put them on top of a tall building or a mountain, or something tall and high. This way, we see that fear and anxiety manifest.

You may be thinking, “why would a character with a crippling fear of heights be on top of a tall building or a mountain?” The answer: the plot gets them there. That is your job as the writer to come up with plot reasons to show these internal conflicts.

How does Winter Soldier make us feel Cap’s unease in the modern world? How does it make us feel his longing for the past? He goes to the Smithsonian and sees the WWII displays about him and the Howling Commandos (which includes his best friend Bucky). He goes and visits the now elderly Peggy Carter and they discuss the past. These ACTIONS demonstrate what he is feeling inside.

Visual storytelling, telling the story through action, is about what happens within the scene, but it is also about the very scenes we choose. The writers of Winter Soldier picked scenes that were inherently active to show these traits of Captain America. As you go through your outline and see what scenes are necessary for each step in the outline, make sure that you are thinking of active scenes.

In the Establishment step for our hypothetical construction worker running for mayor plot, we know the things we need to setup at that stage. However, there are numerous ways to relate that information.

For example, we could reveal that Bill is good at his construction job through a conversation with his wife as she tells him how amazing he is at building things. Is that visual? And active? Not really.

We could make the point of Bill being fine at his job because he gets a thank you note from a homeowner telling him how pleased they are with the work he did. That’s a little more visual and a little more active, but only a little more of both.

We could actually show Bill doing great work on a building site. Now that is visual and active. That is telling and not showing.

Active scenes are active by their nature, by their very structure. When your scenes are active, it is much easier to make the characters within the scenes active. Therefore at each step of the outline, think of scenes that are inherently active.

Dialogue

Most screenwriters love writing dialogue. Many times, the writing of dialogue is what has attracted us to the medium. We have favorite quotes from movies. We have created witty turns of phrases that we know would work so well on screen.

So we like writing dialogue. Therefore, we write a lot of it. Way too much of it.

If you are new to screenwriting, you might think that dialogue is the most important part of a script. The truth is, no, it is not. In fact, there’s a reason we have waited this long to talk about it. The other elements of a script we have focused on so far – structure, character arc, etc. – are all more important than dialogue.

Yes, in certain movies dialogue is more prominent, more critical, than other movies. Yes, dialogue is important. All parts of the script are important. Yet, many beginning screenwriters overemphasize dialogue, exaggerating its importance to the overall script.

Let’s start with some basics. To write good dialogue you need to know your characters. You need to know who they are as people. This means knowing their personalities. Are they a happy-go-lucky fun loving type? Are they a dark brooder? Knowing that personality gives you a grasp of how they should talk.

Knowing where they are from gives you an idea of diction. When you combine personality with background (where they grew up) you can create how a character speaks.

Keep dialogue short. Often, we don’t trust what we have written. We think the audience will not get the point we are making the first time. So then we make the point again, just phrasing it differently. Remember, the audience is savvy. They get the point. Once you have made that point in dialogue, move on.

Yes, every bit of dialogue should have a point to it, just like every scene has a point to it. The point of the dialogue could be a key piece of plot information. It could be a key piece of character information. Dialogue is not frivolous. It is part of telling this story.

How someone says something reveals meaning. Think about a person being asked how they are doing and they reply “great” with a beaming smile. Their sincerity shines through. They DO feel great.

If the person says “great” sarcastically that produces an opposite meaning. How that one word is spoken, the tone, might tell us all we need to know for that scene…

Because, people, generally, do not go into monologues stating exactly what they are thinking and feeling. We call dialogue that flatly states exactly what someone is thinking and/or feeling “on the nose.”

People speak with nuance, subtlety. Look at the scene in Winter Soldier when Cap visits Peggy. There is a moment where Peggy’s memory gets foggy. She is suffering some early stages of dementia. Cap could go into how distressing this is for him, how upsetting it is to see how old she has gotten. However, he talks to her calmly, going along with her.

Through the acting, the way he speaks to her, we know how much he cares for her and how upsetting this is for him. We do not need him to tell us those direct feelings. Speaking those feelings out loud would be redundant; we already KNOW how he is feeling.

When you have a solid, strong structure for your screenplay, and you have a solid, strong structure for a scene, the dialogue is not doing the heavy lifting of storytelling.

Elle in Legally Blonde is a character who talks more openly about her feelings (she talks more in general than Cap does for instance). Yet there is still subtlety and nuance. Everything is not on the nose. When talking to sorority sisters on the phone, she does not express just how difficult Harvard is for her. Her sorority sisters are having fun and Elle knows telling them the full truth would dampen their good time.

As you think about writing dialogue, follow these fundamental steps.

Listen to how people talk. Catch interesting phrases and write them down. Hear how conversations turn on hints and on what is not said. The meaning of a conversation is often BEHIND the words.

Secondly, as mentioned, know the personality and background of your characters. When you know that personality, you know what their surface talk is and the deeper meanings not said.

Thirdly, get to the point and move on.

Lastly, trust the audience. They will get what you are saying the first time.