9.3 Stoichiometry of Gaseous Substances, Mixtures, and Reactions

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Perform stoichiometric calculations involving gaseous substances

- State Dalton’s law of partial pressures and use it in calculations involving gaseous mixtures

The study of the chemical behavior of gases was part of the basis of perhaps the most fundamental chemical revolution in history. French nobleman Antoine Lavoisier, widely regarded as the “father of modern chemistry,” changed chemistry from a qualitative to a quantitative science through his work with gases. He discovered the law of conservation of matter, discovered the role of oxygen in combustion reactions, determined the composition of air, explained respiration in terms of chemical reactions, and more. He was a casualty of the French Revolution, guillotined in 1794. Of his death, mathematician and astronomer Joseph-Louis Lagrange said, “It took the mob only a moment to remove his head; a century will not suffice to reproduce it.”1

As described in an earlier chapter of this text, we can turn to chemical stoichiometry for answers to many of the questions that ask “How much?” The essential property involved in such use of stoichiometry is the amount of substance, typically measured in moles (n). For gases, molar amount can be derived from convenient experimental measurements of pressure, temperature, and volume. Therefore, these measurements are useful in assessing the stoichiometry of pure gases, gas mixtures, and chemical reactions involving gases.

The Pressure of a Mixture of Gases: Dalton’s Law

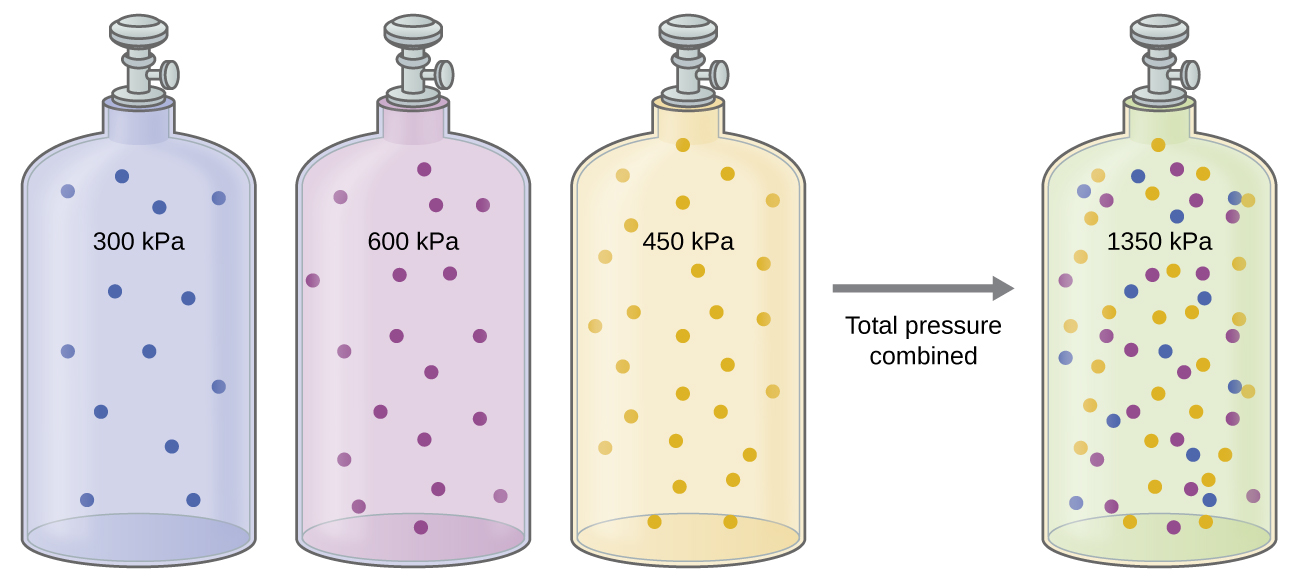

Unless they chemically react with each other, the individual gases in a mixture of gases do not affect each other’s pressure. Each individual gas in a mixture exerts the same pressure that it would exert if it were present alone in the container (Figure 9.18). The pressure exerted by each individual gas in a mixture is called its partial pressure. This observation is summarized by Dalton’s law of partial pressures: The total pressure of a mixture of ideal gases is equal to the sum of the partial pressures of the component gases:

In the equation PTotal is the total pressure of a mixture of gases, PA is the partial pressure of gas A; PB is the partial pressure of gas B; PC is the partial pressure of gas C; and so on.

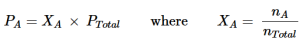

The partial pressure of gas A is related to the total pressure of the gas mixture via its mole fraction (X), a unit of concentration defined as the number of moles of a component of a solution divided by the total number of moles of all components:

where PA, XA, and nA are the partial pressure, mole fraction, and number of moles of gas A, respectively, and nTotal is the number of moles of all components in the mixture.

Example 9.9

The Pressure of a Mixture of Gases:

A 10.0-L vessel contains 2.50 × 10−3 mol of H2, 1.00 × 10−3 mol of He, and 3.00 × 10−4 mol of Ne at 35 °C.

(a) What are the partial pressures of each of the gases?

(b) What is the total pressure in atmospheres?

Solution:

The gases behave independently, so the partial pressure of each gas can be determined from the ideal gas equation, using PV = nRT:

The total pressure is given by the sum of the partial pressures:

Check Your Learning:

A 5.73-L flask at 25 °C contains 0.0388 mol of N2, 0.147 mol of CO, and 0.0803 mol of H2. What is the total pressure in the flask in atmospheres?

1.137 atm

Here is another example of this concept, but dealing with mole fraction calculations.

Example 9.10

The Pressure of a Mixture of Gases:

A gas mixture used for anesthesia contains 2.83 mol oxygen, O2, and 8.41 mol nitrous oxide, N2O. The total pressure of the mixture is 192 kPa.

(a) What are the mole fractions of O2 and N2O?

(b) What are the partial pressures of O2 and N2O?

Solution:

The mole fraction is given by XA = nA/ntotal and the partial pressure is PA = XA × PTotal.

For O2,

and PO2 = XO2 ×PTotal = 0.252 × 192 kPa = 48.4 kPa

For N2O,

and PN2O = XN2O ×PTotal = 0.748 × 192 kPa = 144 kPa

Check Your Learning:

What is the pressure of a mixture of 0.200 g of H2, 1.00 g of N2, and 0.820 g of Ar in a container with a volume of 2.00 L at 20 °C?

1.87 atm

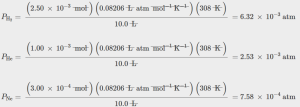

Collection of Gases over Water

A simple way to collect gases that do not react with water is to capture them in a bottle that has been filled with water and inverted into a dish filled with water. The pressure of the gas inside the bottle can be made equal to the air pressure outside by raising or lowering the bottle. When the water level is the same both inside and outside the bottle (Figure 9.19), the pressure of the gas is equal to the atmospheric pressure, which can be measured with a barometer.

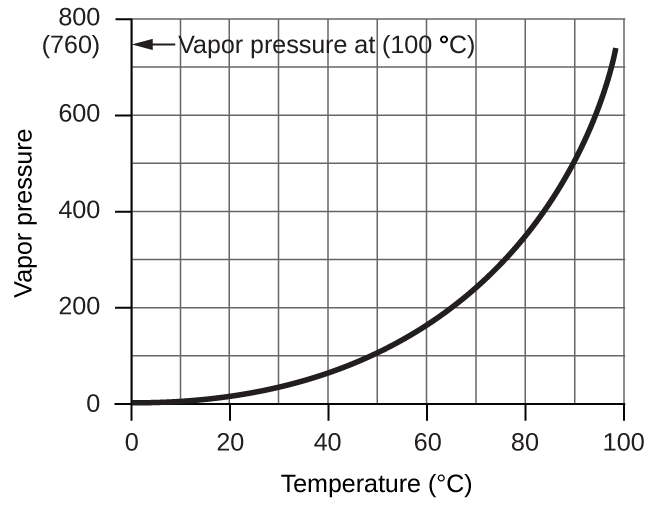

However, there is another factor we must consider when we measure the pressure of the gas by this method. Water evaporates and there is always gaseous water (water vapor) above a sample of liquid water. As a gas is collected over water, it becomes saturated with water vapor and the total pressure of the mixture equals the partial pressure of the gas plus the partial pressure of the water vapor. The pressure of the pure gas is therefore equal to the total pressure minus the pressure of the water vapor—this is referred to as the “dry” gas pressure, that is, the pressure of the gas only, without water vapor. The vapor pressure of water, which is the pressure exerted by water vapor in equilibrium with liquid water in a closed container, depends on the temperature (Figure 9.20); more detailed information on the temperature dependence of water vapor can be found in Table 9.2.

| Vapor Pressure of Ice and Water in Various Temperatures at Sea Level | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | Pressure (torr) | Temperature (°C) | Pressure (torr) | Temperature (°C) | Pressure (torr) | ||

| –10 | 1.95 | 18 | 15.5 | 30 | 31.8 | ||

| –5 | 3.0 | 19 | 16.5 | 35 | 42.2 | ||

| –2 | 3.9 | 20 | 17.5 | 40 | 55.3 | ||

| 0 | 4.6 | 21 | 18.7 | 50 | 92.5 | ||

| 2 | 5.3 | 22 | 19.8 | 60 | 149.4 | ||

| 4 | 6.1 | 23 | 21.1 | 70 | 233.7 | ||

| 6 | 7.0 | 24 | 22.4 | 80 | 355.1 | ||

| 8 | 8.0 | 25 | 23.8 | 90 | 525.8 | ||

| 10 | 9.2 | 26 | 25.2 | 95 | 633.9 | ||

| 12 | 10.5 | 27 | 26.7 | 99 | 733.2 | ||

| 14 | 12.0 | 28 | 28.3 | 100.0 | 760.0 | ||

| 16 | 13.6 | 29 | 30.0 | 101.0 | 787.6 | ||

Example 9.11

Pressure of a Gas Collected Over Water:

If 0.200 L of argon is collected over water at a temperature of 26 °C and a pressure of 750 torr in a system like that shown in Figure 9.19, what is the partial pressure of argon?

Solution:

According to Dalton’s law, the total pressure in the bottle (750 torr) is the sum of the partial pressure of argon and the partial pressure of gaseous water:

Rearranging this equation to solve for the pressure of argon gives:

The pressure of water vapor above a sample of liquid water at 26 °C is 25.2 torr (Appendix E), so:

Check Your Learning:

A sample of oxygen collected over water at a temperature of 29.0 °C and a pressure of 764 torr has a volume of 0.560 L. What volume would the dry oxygen have under the same conditions of temperature and pressure?

0.583 L

Chemical Stoichiometry and Gases

Chemical stoichiometry describes the quantitative relationships between reactants and products in chemical reactions.

We have previously measured quantities of reactants and products using masses for solids and volumes in conjunction with the molarity for solutions; now we can also use gas volumes to indicate quantities. If we know the volume, pressure, and temperature of a gas, we can use the ideal gas equation to calculate how many moles of the gas are present. If we know how many moles of a gas are involved, we can calculate the volume of a gas at any temperature and pressure.

Avogadro’s Law Revisited

Sometimes we can take advantage of a simplifying feature of the stoichiometry of gases that solids and solutions do not exhibit: All gases that show ideal behavior contain the same number of molecules in the same volume (at the same temperature and pressure). Thus, the ratios of volumes of gases involved in a chemical reaction are given by the coefficients in the equation for the reaction, provided that the gas volumes are measured at the same temperature and pressure.

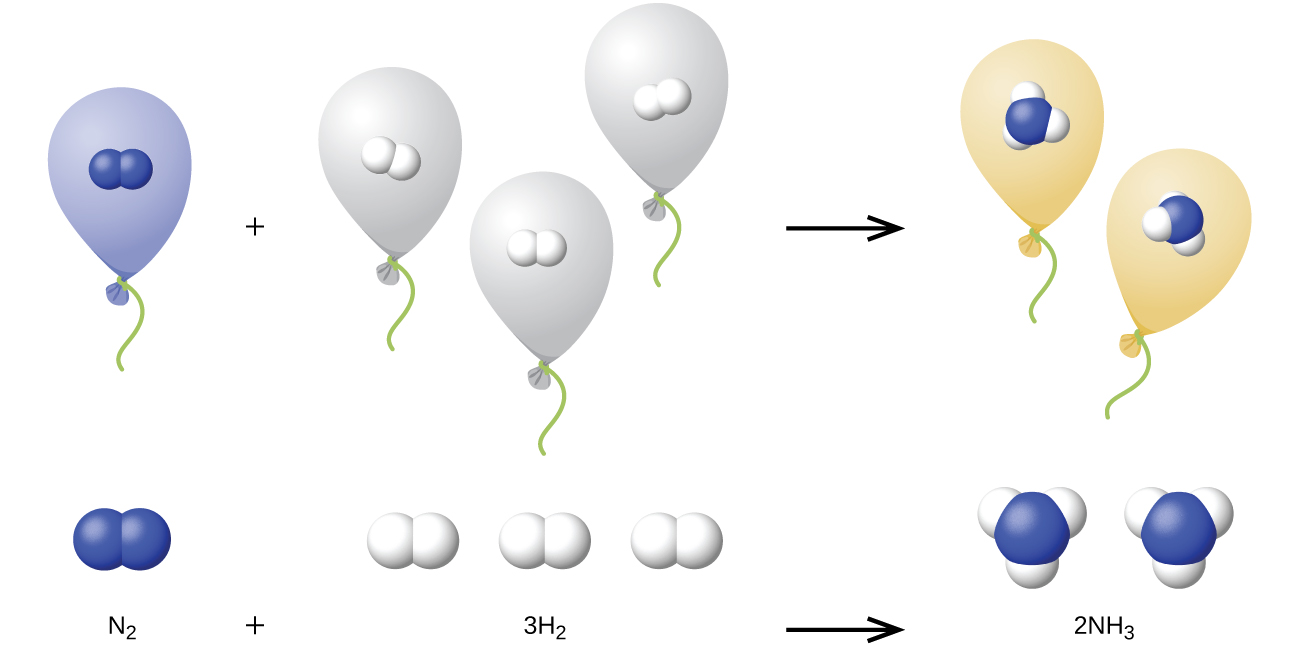

We can extend Avogadro’s law (that the volume of a gas is directly proportional to the number of moles of the gas) to chemical reactions with gases: Gases combine, or react, in definite and simple proportions by volume, provided that all gas volumes are measured at the same temperature and pressure. For example, since nitrogen and hydrogen gases react to produce ammonia gas according to N2(g) + 3H2(g) ⟶ 2NH3(g), a given volume of nitrogen gas reacts with three times that volume of hydrogen gas to produce two times that volume of ammonia gas, if pressure and temperature remain constant.

The explanation for this is illustrated in Figure 9.21. According to Avogadro’s law, equal volumes of gaseous N2, H2, and NH3, at the same temperature and pressure, contain the same number of molecules. Because one molecule of N2 reacts with three molecules of H2 to produce two molecules of NH3, the volume of H2 required is three times the volume of N2, and the volume of NH3 produced is two times the volume of N2.

Example 9.12

Reaction of Gases:

Propane, C3H8(g), is used in gas grills to provide the heat for cooking. What volume of O2(g) measured at 25 °C and 760 torr is required to react with 2.7 L of propane measured under the same conditions of temperature and pressure? Assume that the propane undergoes complete combustion.

Solution:

The ratio of the volumes of C3H8 and O2 will be equal to the ratio of their coefficients in the balanced equation for the reaction:

From the equation, we see that one volume of C3H8 will react with five volumes of O2:

A volume of 13.5 L of O2 will be required to react with 2.7 L of C3H8.

Check Your Learning:

An acetylene tank for an oxyacetylene welding torch provides 9340 L of acetylene gas, C2H2, at 0 °C and 1 atm. How many tanks of oxygen, each providing 7.00 × 103 L of O2 at 0 °C and 1 atm, will be required to burn the acetylene?

3.34 tanks (2.34 × 104 L)

Example 9.13

Volumes of Reacting Gases:

Ammonia is an important fertilizer and industrial chemical. Suppose that a volume of 683 billion cubic feet of gaseous ammonia, measured at 25 °C and 1 atm, was manufactured. What volume of H2(g), measured under the same conditions, was required to prepare this amount of ammonia by reaction with N2?

Solution:

Because equal volumes of H2 and NH3 contain equal numbers of molecules and each three molecules of H2 that react produce two molecules of NH3, the ratio of the volumes of H2 and NH3 will be equal to 3:2. Two volumes of NH3, in this case in units of billion ft3, will be formed from three volumes of H2:

The manufacture of 683 billion ft3 of NH3 required 1020 billion ft3 of H2. (At 25 °C and 1 atm, this is the volume of a cube with an edge length of approximately 1.9 miles.)

Check Your Learning:

What volume of O2(g) measured at 25 °C and 760 torr is required to react with 17.0 L of ethylene, C2H4(g), measured under the same conditions of temperature and pressure? The products are CO2 and water vapor.

51.0 L

Example 9.14

Volume of Gaseous Product:

What volume of hydrogen at 27 °C and 723 torr may be prepared by the reaction of 8.88 g of gallium with an excess of hydrochloric acid?

Solution:

Convert the provided mass of the limiting reactant, Ga, to moles of hydrogen produced:

Convert the provided temperature and pressure values to appropriate units (K and atm, respectively), and then use the molar amount of hydrogen gas and the ideal gas equation to calculate the volume of gas:

Check Your Learning:

Sulfur dioxide is an intermediate in the preparation of sulfuric acid. What volume of SO2 at 343 °C and 1.21 atm is produced by burning l.00 kg of sulfur in excess oxygen?

1.30 × 103 L

Greenhouse Gases and Climate Change

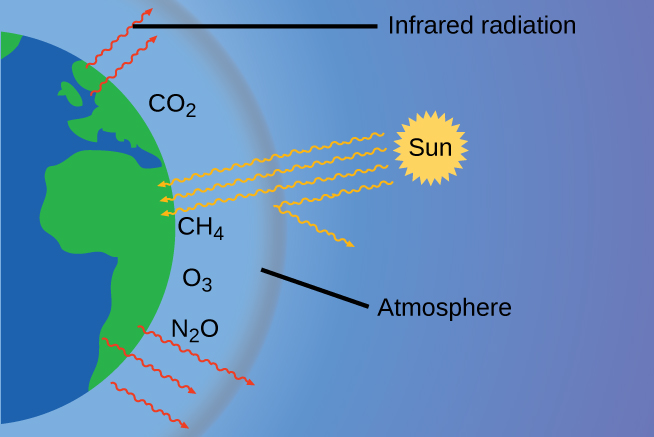

The thin skin of our atmosphere keeps the earth from being an ice planet and makes it habitable. In fact, this is due to less than 0.5% of the air molecules. Of the energy from the sun that reaches the earth, almost 1/3 is reflected back into space, with the rest absorbed by the atmosphere and the surface of the earth. Some of the energy that the earth absorbs is re-emitted as infrared (IR) radiation, a portion of which passes back out through the atmosphere into space. Most if this IR radiation, however, is absorbed by certain atmospheric gases, effectively trapping heat within the atmosphere in a phenomenon known as the greenhouse effect. This effect maintains global temperatures within the range needed to sustain life on earth. Without our atmosphere, the earth’s average temperature would be lower by more than 30 °C (nearly 60 °F). The major greenhouse gases (GHGs) are water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, and ozone. Since the Industrial Revolution, human activity has been increasing the concentrations of GHGs, which have changed the energy balance and are significantly altering the earth’s climate (Figure 9.22).

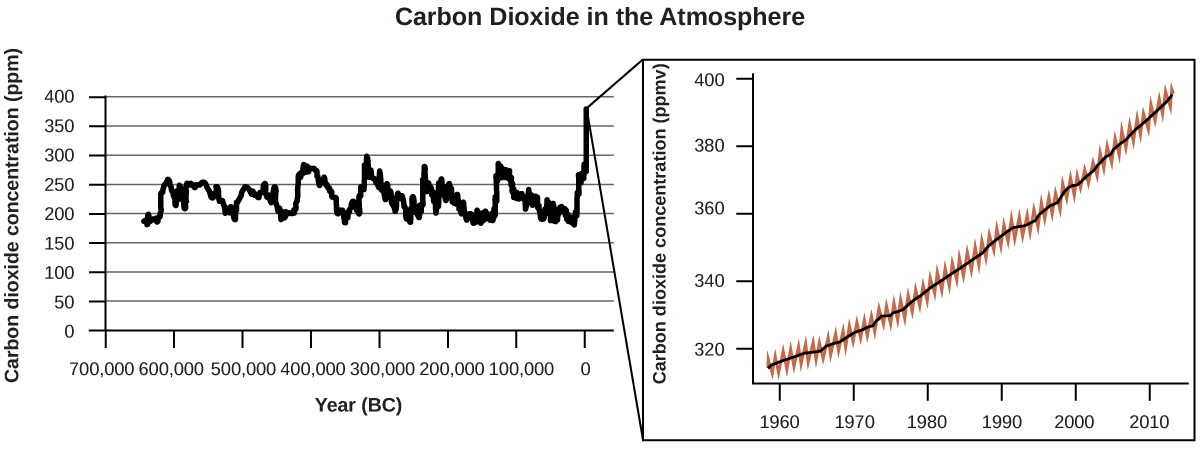

There is strong evidence from multiple sources that higher atmospheric levels of CO2 are caused by human activity, with fossil fuel burning accounting for about ¾ of the recent increase in CO2. Reliable data from ice cores reveals that CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is at the highest level in the past 800,000 years; other evidence indicates that it may be at its highest level in 20 million years. In recent years, the CO2 concentration has increased preindustrial levels of ~280 ppm to more than 400 ppm today (Figure 9.23).

Link to Learning

Click here to see a 2-minute video explaining greenhouse gases and global warming.

Susan Solomon

Atmospheric and climate scientist Susan Solomon (Figure 9.24) is the author of one of The New York Times books of the year (The Coldest March, 2001), one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world (2008), and a working group leader of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which was the recipient of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize. She helped determine and explain the cause of the formation of the ozone hole over Antarctica, and has authored many important papers on climate change. She has been awarded the top scientific honors in the US and France (the National Medal of Science and the Grande Medaille, respectively), and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the Royal Society, the French Academy of Sciences, and the European Academy of Sciences. Formerly a professor at the University of Colorado, she is now at MIT, and continues to work at NOAA.

Link to Learning

For more information, watch this video about Susan Solomon.

Key Concepts and Summary

The ideal gas law can be used to derive a number of convenient equations relating directly measured quantities to properties of interest for gaseous substances and mixtures. Dalton’s law of partial pressures may be used to relate measured gas pressures for gaseous mixtures to their compositions. Avogadro’s law may be used in stoichiometric computations for chemical reactions involving gaseous reactants or products.

Key Equations

- PTotal = PA + PB + PC + … = ƩiPi

- PA = XA PTotal

- XA = nA/ntotal

Footnotes

- 1“Quotations by Joseph-Louis Lagrange,” last modified February 2006, accessed February 10, 2015, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Quotations/Lagrange.html

Glossary

- Dalton’s law of partial pressures

- total pressure of a mixture of ideal gases is equal to the sum of the partial pressures of the component gases

- mole fraction (X)

- concentration unit defined as the ratio of the molar amount of a mixture component to the total number of moles of all mixture components

- partial pressure

- pressure exerted by an individual gas in a mixture

- vapor pressure of water

- pressure exerted by water vapor in equilibrium with liquid water in a closed container at a specific temperature