Synovial Structures

Anatomy of structures containing synovial fluid

(edited Smallwood text)

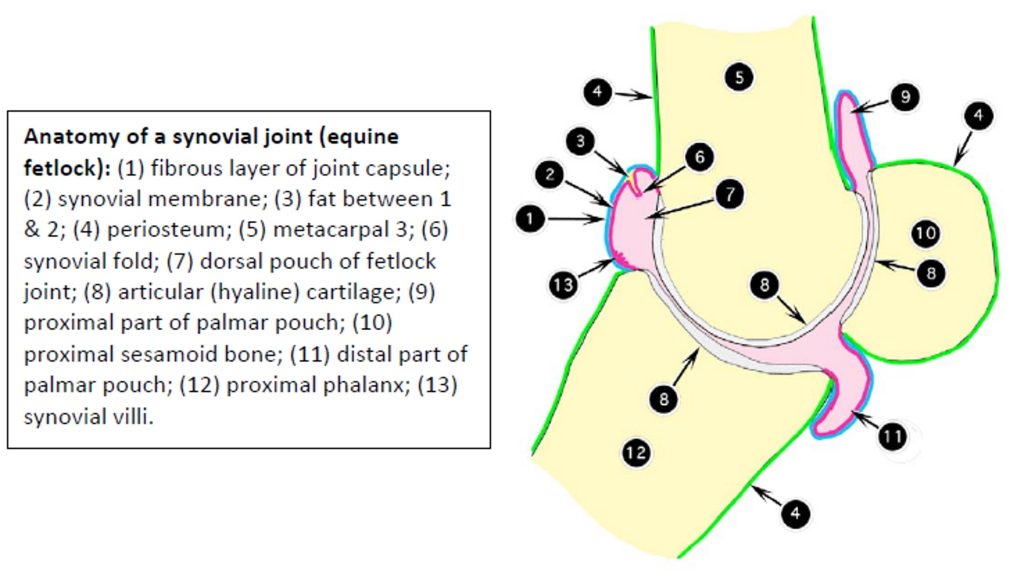

We have three types of synovial structures to deal with as veterinarians: bursae, tendon sheaths, and joint capsules. They all share a common feature, the presence of a synovial membrane. This is a membrane capable of regulating the production and resorption of synovial fluid, which is a specialized type of extracellular fluid associated with lubrication.

In basic terms, whenever two structures must rub on one another, we need lubrication to reduce friction, which causes wear and heat production. Most body parts are “factory installed” and are designed to last for the lifetime of the unit. Having them replaced is not only expensive but often yields less than optimal results, regardless of the skill of the surgeon.

Let’s talk about pressure. Whenever two body parts rub against one another repeatedly, there is the potential for fatigue of one or both parts. Rather than thinking of each of these pressure absorbers as a separate entity, it is better to consider them as a progression of the law of demand and supply.

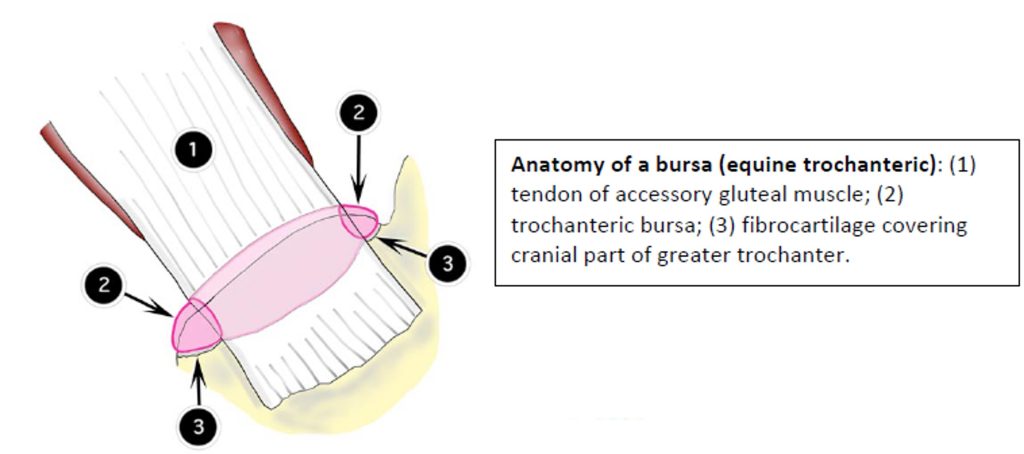

First, we have the situation in which one structure rubs on another over a single contact surface, such as the accessory gluteal tendon over the greater trochanter – the need for lubrication is limited to one side and a short distance. The problem is friction – one side, for a short distance, and the solution is the formation of a bursa. Next, we have a tunnel to deal with. The problem is friction on all sides over a variable length – a bursa is not sufficient, so a more elaborate set-up is needed; the solution is a tendon sheath.

Another problem is that of extreme pressure over a localized area of the tendon; this requires not only lubrication, but strengthening of the tendon to withstand the pressure. One solution is a fibrocartilage pad in the tendon; another solution is ossification of fibrocartilage- that is, a sesamoid bone. The body is basically stingy when it comes to passing out these pressure absorbers; it doesn’t use a tendon sheath if a bursa will do. Now let’s consider the tendon sheath for what it really is. It is a linear structure that lubricates a tendon as it passes through a tight place (tunnel). The tendon is not within the sheath, but is enveloped by it, much like the heart is enveloped by the pericardial sac. The outer layer is attached to the walls of the tunnel and remains stationary as the tendon does its thing; the inner layer is adhered to the tendon and moves with it. Thus, we have two slick surfaces gliding on one another as the tendon moves back and forth. There is a linear connecting fold between the outer and inner layers of the tendon sheath. This is the mesotendon, which, like the mesentery, provides an avenue for vessels and nerves to enter and leave the tendon. It does not typically extend the entire length of the sheath, but has enough slack in it to allow for the normal excursion of the tendon.