MSK LAB 14A – Abdominal wall myology

Learning Objectives

- Identify the linea alba and describe the advantages of using this structure for an incision into the abdomen

- Describe the inguinal canal and identify the superficial inguinal ring

- Identify the four primary muscles of the abdominal wall

- Identify the rectus sheaths and the clinical relevance of the external rectus sheath

- Identify associated structures of the ungulate abdominal wall, define the boundaries of the paralumbar fossa

- Recall and visualise the layers incised for a laparotomy, ventral midline or paramedian incision of the abdominal wall

Lab introduction:

Moving caudally from the thoracic wall, we will now dissect and identify the muscles of the abdominal wall. There is also an important passage way through the abdominal wall that we can consider at this time.

Dissect: Read the following descriptions of muscles and perform dissection as directed. All dissection is continued on the left side of the cadaver. Our intent is to not enter the abdominal cavity at this time. Refer to ungulate prosected cadavers for the comparative anatomy as instructed.

Linea alba, Inguinal canal

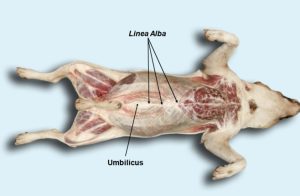

Before we dissect, the linea alba and the inguinal canal and its rings should be familiar. The linea alba (literally the ‘white line’) is the fibrous ventral midline junction of tissues, and it extends from the xiphoid cartilage to the pelvic symphysis. It is similar in concept to the dorsal midline raphe of the neck (considered back in thoracic limb and neck anatomy). The linea alba is the common insertion point for the lateral abdominal wall muscles, and separates the left and right rectus abdominis muscles. The umbilicus is located in the linea alba (its cutaneous appearance previously identified in the common integument lab). The linea alba is wider cranially, and narrows caudally towards the pelvis.

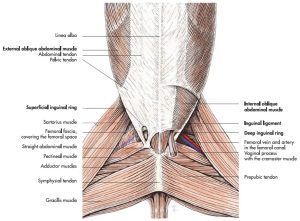

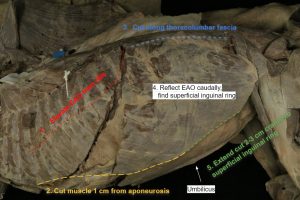

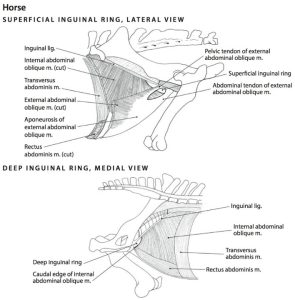

The inguinal canal (this structure is present bilaterally) is a passageway, a fissure, through the abdominal wall muscles, for nerves, vessels, and genital tissues (sex dependent) to pass through, in leaving or entering the abdominal cavity. The canal is entered or exited internally (i.e. on the inner surface of the abdominal wall) at the deep inguinal ring. Externally, on the outer surface of the abdominal wall, the canal is entered or exited at the superficial inguinal ring. The superficial inguinal ring is a slit in the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique m. We will study these structures in detail later and for now our goal is to avoid their disruption while dissecting the abdominal wall muscles. Look at the diagram and image below to help envision where the superficial inguinal rings are located in the inguinal region of the cadaver. The superficial inguinal ring is typically indistinct at this point in the dissection because it is covered by layers of fascia.

Observe: Examine the abdominal ventral midline of the cadaver to identify the linea alba (it may be partially covered by fascia, which can be reflected and discarded) and the umbilicus. Determine the location of the superficial inguinal ring on the left side.

Clinical relevance: surgical access to the abdominal cavity via the linea alba

Surgical approach to the abdomen is most commonly performed through a ventral midline incision i.e. through the linea alba. The advantages include:

- A relatively bloodless incision (after the skin and subcutaneous tissue is incised) because the collagenous linea alba has minimal vascularity (compared to the adjacent muscles),

- The linea alba has minimal sensory innervation, so there is less pain directly associated with its incision, and

- The linea alba has strong tensile strength and therefore holds suture securely (compared to the minimal holding strength of muscle).

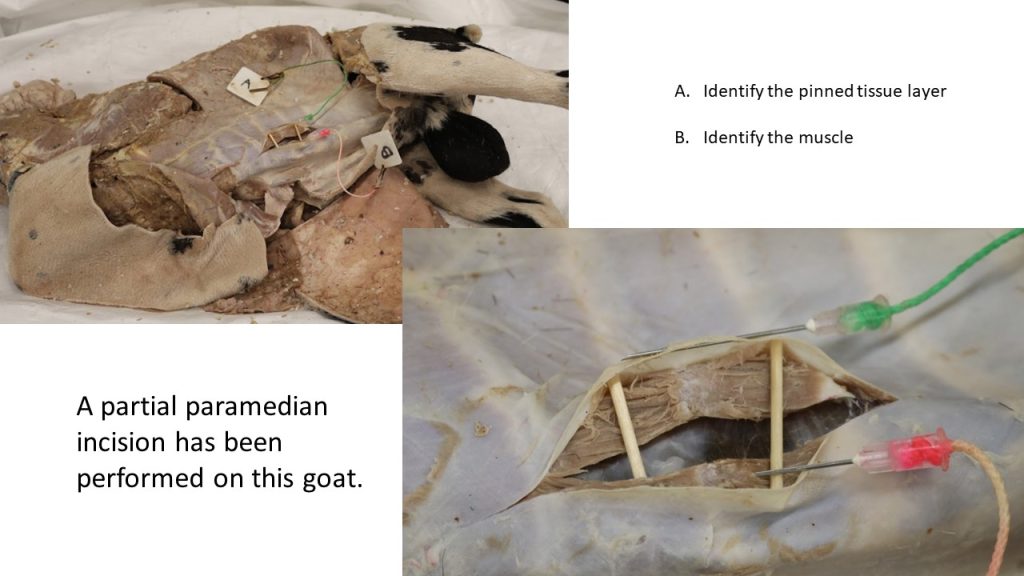

Sometimes an incision parallel to the linea alba (known as a paramedian incision) is made intentionally, and more on this a little further on.

- Muscles of the abdominal wall and the medial side of the thigh of the dog. Schematic, ventral aspect. 7

- Dog linea alba. 40

- Dog inguinal ring

Dissect: As the following incisions are made, be careful of the depth of the incision in an effort to avoid entering the abdominal cavity and slicing viscera. The cadaver is placed in right lateral recumbency to dissect the left abdominal wall. If any cutaneus trunci m. and superficial fascia remain, reflect and excise those tissues now and discard.

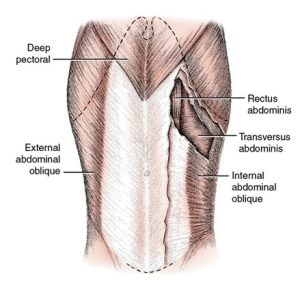

Muscles of the abdominal wall

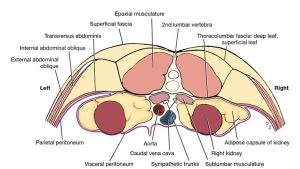

The four abdominal muscles, named from external to internal, are the external abdominal oblique, the internal abdominal oblique, the rectus abdominis, and the transversus abdominis muscles. When they contract, they aid in urination, defecation, parturition, respiration, or locomotion. These muscles are covered superficially by the abdominal fasciae and on the deep surface, by the transversalis fascia, which in turn is covered by peritoneum (structures to be seen in the alimentary tract unit).

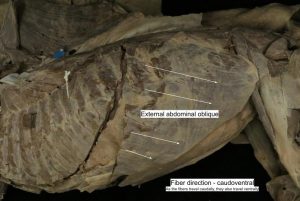

External abdominal oblique m.

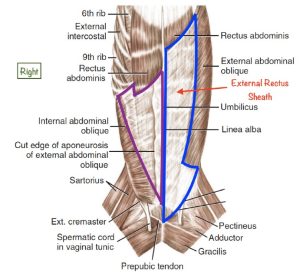

The external abdominal oblique m. covers the ventral half of the lateral thoracic wall and the lateral part of the abdominal wall. The costal part arises from the last ribs. The lumbar part arises from the last rib and from the thoracolumbar fascia. The fibers of this muscle run caudoventrally. In the ventral abdominal wall, this muscle forms a wide aponeurosis that inserts on the linea alba and the prepubic tendon. The thickened caudal margin of the aponeurosis, extending along the shaft of the ilium is called the inguinal ligament. The aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique contributes to the external rectus sheath (see further along).

Dissect: Identify the external abdominal oblique m. and refer to annotated image below of incision lines to be made. Elevate the origins of the external abdominal oblique m. from its rib attachments and reflect it caudally, finding the plane between this muscle and the underlying internal abdominal oblique m. Cut the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique m. along a line about 1 cm from its junction with its muscle fibers, caudally to the level of the umbilicus, but no further at this time. Cut the external abdominal oblique m. dorsally at its thoracolumbar fascia origins. The muscle should be reflected back as a sheet, having been released on 3 sides at this time, and still anchored caudally at its inguinal ligament margin. The cut in the aponeurosis can be extended a little more caudally at this point, once the location of the superficial inguinal ring is confirmed, stopping 2-3 cms cranial to this structure. Inguinal anatomy will be explored in the alimentary and urogenital units.

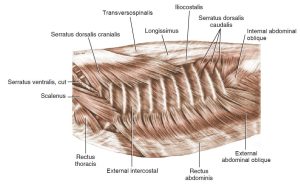

- Superficial muscles of thoracic cage, lateral aspect. 3

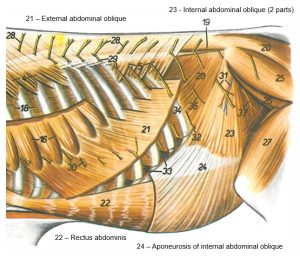

- Muscles of abdominal wall, ventral view. 1

- Dog abdominal wall

- Dog abdominal wall

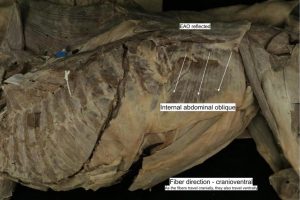

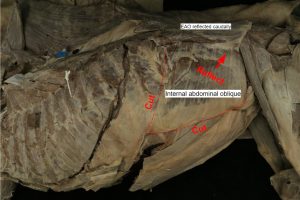

Internal abdominal oblique m.

The internal abdominal oblique m. arises from the superficial leaf of the thoracolumbar fascia caudal to the last rib, in common with the lumbar part of the external abdominal oblique, and from the tuber coxae and adjacent portion of the inguinal ligament. Its fibers run cranioventrally. It inserts by a wide aponeurosis on the costal arch, the linea alba and the prepubic tendon. At the rectus abdominis lateral margin it is fused with the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique to form the external sheath of the rectus abdominis m. More specifically, in the cranial abdomen, at the lateral border of the rectus abdominis, the aponeurosis of the internal abdominal oblique (IAO) splits and passes on both sides of the rectus abdominis to insert on the linea alba. Therefore, the IAO m. also contributes to the internal rectus sheath.

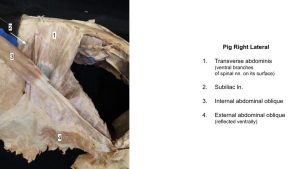

Dissect: Refer to annotated image below showing incision lines to be made. Cut the attachment of the internal abdominal oblique m. along the costal arch and last rib. Cut the aponeurosis of the internal abdominal oblique m. along a line about 1 cm from its junction with its muscle fibers. Carefully find the separation between the internal abdominal oblique m. and the very thin underlying transversus abdominis m., and reflect the internal abdominal oblique m. caudodorsally towards its tuber coxae attachment. The transversus abdominis m. (described below) should now be visible, and it is the remaining lateral abdominal wall muscle layer to be identified. Parallel branches of spinal nerves travel on the external surface of the transversus abdominis m., and this feature helps with identification of the muscle. Do not cut the transversus abdominis m.

- Superficial muscles of thoracic cage, lateral aspect. 3

- Muscles of abdominal wall, ventral view. 1

- Dog abdominal wall

- Dog abdominal wall

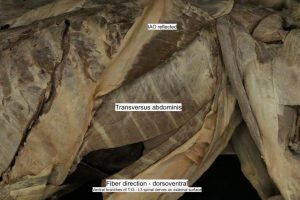

Transversus abdominis m.

The transversus abdominis m. is medial to the internal abdominal oblique and the rectus abdominis. Its fibers run transversely (i.e. dorsoventrally aligned). The muscle arises dorsally from the medial surfaces of the last four or five ribs and from the transverse processes of all the lumbar vertebrae by means of the deep leaf of the thoracolumbar fascia. Its aponeurosis attaches to the linea alba after crossing the internal surface of the rectus abdominis m. Except for its most caudal part, the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis m. forms the internal sheath of the rectus abdominis. The most caudal portion joins the external sheath and fuses with the linea alba and prepubic tendon. The internal surface of the transverse abdominis m. is lined by transversalis fascia, then parietal peritoneum. These inner two layers complete the abdominal wall anatomy and will be viewed when the abdominal cavity is opened in later units. The peritoneum is the serosal membrane of the abdominal cavity, and lines the space of the peritoneal cavity and the surface of the abdominal viscera. Sometimes fat tissue will accumulate between the peritoneum and the transversalis fascia. The external surface of the transversus abdominis m. is characterized by parallel nerves passing over it. These are medial branches of the ventral branches of T13-L3 spinal nerves (to be revisited in the Nervous unit).

Observe: At this time three (3) muscles forming the lateral abdominal wall have been identified. Note the differently oriented fiber patterns.

Clinical relevance: fiber direction of abdominal wall muscles helps with depth determination of incisions and trauma to the body wall.

- Muscles of abdominal wall, ventral view. 1

- Schematic transection in the lumbar region showing fascial layers. 1

- Dog abdominal wall

Rectus abdominis m.

Moving now to the last abdominal wall muscle, located in a ventral position. The rectus abdominis m. begins cranially as a wide aponeurosis attached to the ventral sternum and extends caudally to the pubis, attaching via the prepubic tendon, to the pecten of the pubis. Left and right muscles are fused on midline at the linea alba. Muscle fibers run craniocaudally, and there are distinct transverse tendinous intersections in the muscle bellies (the cause of the so called ‘six pack’ muscular abdomen appearance). When the muscles contract bilaterally they flex (dorsiflex) the thoracolumbar part of the vertebral column (e.g. when a cat dorsally arches its back).

Observe: Identify the rectus abdominis m. and its cranial aponeurosis on the ventral sternum and attachment to the first costal cartilage and rib.

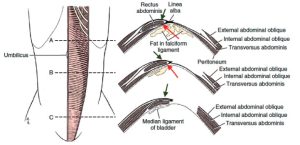

Rectus sheaths

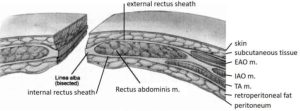

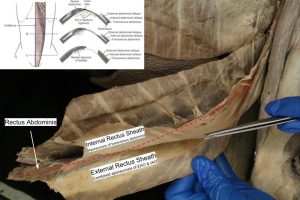

Already mentioned, the rectus abdominis m. is wrapped by fibrous sheaths. These sheaths are formed by the combined fibrous aponeuroses of the lateral abdominal wall muscles. Superficially, the external rectus sheath is formed by the fused aponeuroses of the external and internal abdominal oblique muscles, with the transverse abdominis m. adding in caudally. The layer covering the deep side of the rectus abdominis muscle is the internal rectus sheath, and this relatively weaker sheath is formed by the internal abdominal oblique and transversus abdominis m. aponeuroses, and the sheath is not present at all caudally. The varying contributions to the rectus sheaths along the ventral abdomen are better understood viewing an image, however we are less concerned with knowing these exact contributions and are far more interested in understanding the relative strength and clinical importance of the sheaths.

Clinical relevance: paramedian incisions and rectus sheaths and suture holding.

Most importantly, the external rectus sheath is a strong suture-holding tissue layer that is used in closing ventral abdominal incisions that deviate off the linea alba, or are intentionally paramedian (incision made parallel to the median plane i.e. parallel to the linea alba). Muscle tissue and the internal rectus sheath are not secure holding layers for abdominal wall closure. These layers may be apposed but are not relied on for keeping the abdominal incision intact.

Dissect: Return to the rectus abdominis m. and identify the external rectus sheath. Make a 3-5 cm long incision in the external rectus sheath, about 2 cm lateral and parallel to the linea alba, in the cranial abdomen region. Grasp the cut margin of the sheath with forceps and appreciate its toughness. Just cranial to the umbilicus, gently slide down the surface of the transverse abdominis m. to its aponeurosis. As the aponeurosis passes on the deep surface of the rectus abdominis m. it is called the internal rectus sheath. More cranially, a layer from the internal abdominal oblique aponeurosis also contributes to the internal sheath and may be identifiable. Caudal to the umbilicus, there is discontinuation of the internal rectus sheath as the transversus abdominis m. aponeurosis transitions from a deep to superficial location, to join the external rectus sheath.

- Muscles of abdominal wall, ventral view. 1

- Ventral view of the abdominal wall. On the right side of the dog, the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle (EAO) has been transected and removed, revealing the underlying aponeurosis of the internal abdominal oblique muscle (IAO), outlined in purple. Deep to the aponeurosis of the IAO, the rectus abdominis muscle can be visualized. On the left side, the EAO is intact and outlined in blue. The combination of the aponeuroses of the EAO and IAO form the external rectus sheath which covers the ventral surface of the rectus abdominis at the level of the cranial abdomen (red arrow). 3

- The sheath of muscle rectus abdominis with cross-sections at three levels. At level A in the diagram above, the aponeuroses of the EAO and IAO combine to form the external rectus sheath (green arrow). The internal rectus sheath is formed by a combination of the aponeuroses of the IAO and the transversus abdominis muscles (red arrow). 3

- Abdominal wall muscles, linea alba and rectus sheaths. 6

- Dog rectus sheath

Ungulate comparative anatomy

Observe: Refer to prosected ungulate cadavers to learn the comparative abdominal wall anatomy and features considered more frequently in these species.

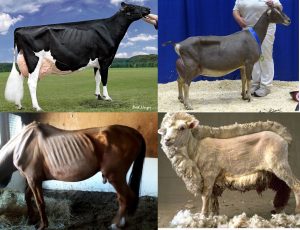

External topography and landmarks

The lateral part of the abdominal wall that is not protected by the rib cage, pelvis, or thigh is called the flank. In the horse, the last rib is very close to the tuber coxae, leaving only about one hand’s-width space in the upper flank. Surgical intervention in this area is therefore somewhat limited in the horse, however laparoscopy is readily performed via the flank in the horse. The ruminant has a large flank area, and this allows for comparatively convenient access to the abdominal cavity. The flank fold is a skin fold that extends from the caudoventral abdominal wall to the craniomedial aspect of the thigh near the stifle. The cutaneus trunci m. is contained within this fold, which accounts for the active twitching of the fold, especially in the horse (refer back to the Common Integument system). The fold can also be used as a handhold in the restraint of calves and small ruminants- hence, the phrase “flanking a calf down.”

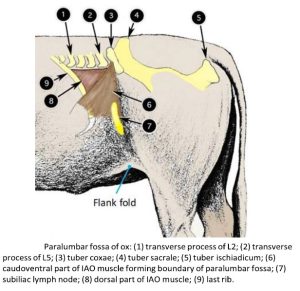

Paralumbar Fossa: This triangular depression in the upper part of the flank is especially prominent in the standing domestic ruminant. It is an important surgical area in the ruminant. It is bound dorsally by the transverse processes of lumbar vertebrae L2 to L5, cranially by the last rib, and caudoventrally by the tense, palpable, and visible band of the ventral part of the internal abdominal oblique (IAO) m. This raised tense band of the muscle is created passively by the weight of the abdominal viscera. In the living horse and pig, the paralumbar fossa is small in size and often not a fossa at all in normally or excessively conditioned animals, so it is less apparent.

Observe: Refer to prosected ungulate cadavers and identify the flank region, and the paralumbar fossa, defining its boundaries. Review articulated skeletons to appreciated the lumbar vertebrae.

Clinical relevance: flank and paralumbar fossa

- Paralumbar fossa of ox. 2

- The paralumbar fossa is most evident in a dairy ruminant with a lower body condition score. Meat animals or wool sheep will be less obvious. Horses must be severely underweight to be evident.

Clinical relevance and clinical application Q2:

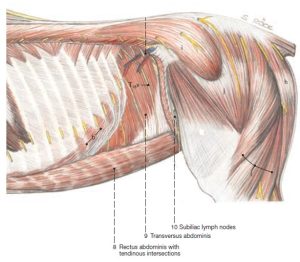

Subiliac lymph nodes

The subiliac (aka ‘prefemoral’) lymph nodes of ungulates drain the flank area and skin over the thigh and stifle, with efferents (lymph channels exiting the node) passing to the medial iliac nodes (and to the external iliac lnn. in ruminant, pig). They are difficult to find in the horse, as they are a discreet cluster of small nodes. The nodes are readily found in the ruminant and pig. These lymph nodes are not present in the dog and the cat.

Observe: Refer to prosected ungulates. Locate these lymph nodes in the fascia along the cranial aspect of the thigh, proximal to the stifle and below the tuber coxae of the ilium.

Clinical relevance: physical examination

- Deep dissection of the horse abdominal wall. 14

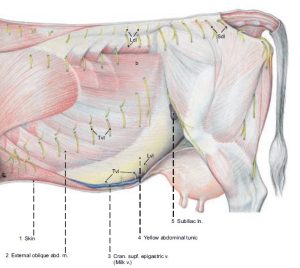

- Superficial dissection of the cow abdominal wall. 13

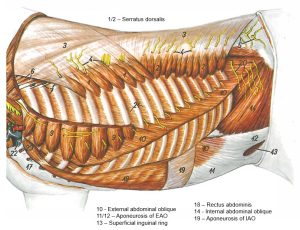

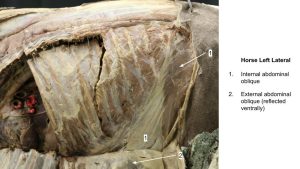

Abdominal Wall – lateral muscles

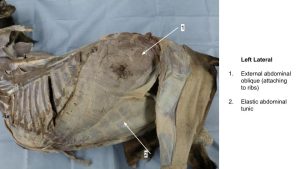

As in carnivores, the lateral abdominal wall of ungulates is formed by two oblique and one transverse abdominal muscle to provide a three-ply arrangement, with fibers in each successive layer oriented in a different direction (the rectus abdominis m. is present too, part of the ventral wall). This 3-ply arrangement of course provides for much greater strength than if it were a cheaper, single-ply model. Supporting several hundred pounds of viscera is a big job in the horse and the ox. These large herbivores do so with passive support in the form of the elastic abdominal tunic (aka tunica flava abdominis = yellow abdominal tunic), which is a modification of the deep fascia that closely invests the external abdominal oblique m. This elastic tunic takes some of the stress off the abdominal muscles and acts as a sort of “living girdle.”

Observe: Identify the external abdominal oblique m. and the elastic abdominal tunic in the prosected ungulates. Note the musculotendinous junction, (the curved line along which muscle meets its aponeurosis). Fold the muscle back to its original position, and note the location of the muscle-aponeurosis junction. The ‘heave line’ develops along this junction in horses with chronic respiratory effort (see Clinical Relevance box below).

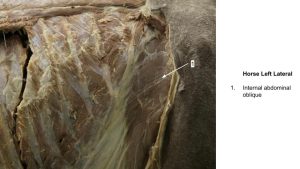

The internal abdominal oblique m. of the ruminant covers the entire paralumbar fossa and is divided into two parts. FYI – the two parts are readily separated in the goat and calf cadavers due to the tenuous connection between them. The dorsal part terminates on the last rib, whereas the aponeurosis of the caudoventral part passes lateral to the costal arch and continues to the linea alba. Because the caudoventral part of the muscle is under tension by the weight of the abdominal viscera in the standing ruminant, a ridge is formed along its upper border. It is this tense muscle ridge that forms the caudoventral diagonal border of the paralumbar fossa.

Observe: Identify the internal abdominal oblique m. in the prosected cadavers.

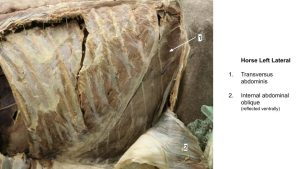

The transverse abdominis m. fibers run in a dorsoventral direction. This muscle lies deep to the internal abdominal oblique m. In addition to the muscle fiber direction, the transverse abdominis m. is characterized by the presence of parallel branches of spinal nerves passing on the muscle’s external surface. As mentioned for the carnivore, the internal surface of the transverse abdominis m. is lined by two more layers of tissue, the transversalis fascia and then the parietal peritoneum (the serous membrane of the abdomen).

Observe: Reflect the internal abdominal oblique to identify and view the surface of the transverse abdominis m. This should reveal the large medial branches of the ventral branches of the spinal nerves crossing the surface of the transverse abdominis m.. In the ruminant note that in the area of the paralumbar fossa, the transverse abdominis muscle is aponeurotic, not muscular. Thus, surgical incisions limited to the paralumbar fossa of the ruminant do not typically involve cutting the TA muscle fibers proper, only its aponeurosis. In contrast, note that the transverse abdominis m. of the horse is fleshy in the paralumbar fossa region, and the same in the pig, albeit thin!

Clinical relevance: ‘heave line’

- Horse with heaves, showing the hypertrophy of the EAO. University of Kentucky

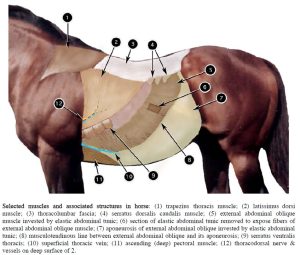

Observe: Review the caudodorsal corner of the equine flank to identify vessel stumps just cranial to the tuber coxae. These are cut branches of the deep circumflex iliac a. (their short distance from their origin on the descending aorta will be visited in the Cardiovascular unit.)

Clinical relevance: vessels in the flank and surgical incisions.

These vessels, which specifically, are cranial branches of the deep circumflex iliac artery and vein, may have to be dealt with in a surgery involving a dorsal flank incision in the horse (or possibly a ruminant). Significant hemorrhage is possible from cut vessels.

- Selected muscles and associated structures in horse. 2

- Horse. Deep dissection of thorax and abdominal wall. 11

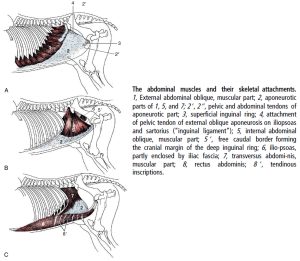

- The abdominal muscles and their skeletal attachments. 8

- Paralumbar fossa of ox. 2

- Dissection of the cow abdominal wall. 11

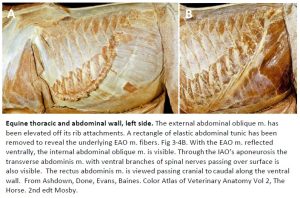

- Equine thoracic and abdominal wall, left side. 15

- Equine abdominal wall, left side showing the transversus abdominis m. with ventral branches of the spinal nerves passing over its surface. 15

Rectus abdominis m., rectus sheaths, linea alba

The rectus abdominis m. extends craniocaudally along the ventral abdominal wall. The left and right muscles are separated by the linea alba on midline. As in carnivores the external and internal rectus sheaths are formed by the aponeuroses of the lateral abdominal wall muscles.

Observe: Refer to the prosected ungulate cadavers and identify the rectus abdominis m., external rectus sheath, internal rectus sheath, and linea alba. A cross-section tissue slice of the ventral abdominal wall may also be available to view these features and how they relate to each other.

The transverse abdominis m. passes deep to the rectus abdominis m., thereby forming the internal rectus sheath, with cranial contributions from the internal abdominal oblique m. Caudally the transverse abdominis m. aponeurosis passes superficial to the rectus abdominis m., contributing to the external sheath in this location (can you recall the anatomy of the linea alba and rectus sheaths in small animals? – yes, it is very similar!).

Abdominal wall incision anatomy

We have viewed most of the layers of the abdominal wall that must be incised to enter the peritoneal cavity and the deepest layers (transversalis fascia and peritoneum) will be considered once the abdomen is opened in later units. For now it is valuable to apply this wall anatomy to incisions made, as the more we understand the sequence of the layers we are incising the more comfortable we are making the incision and knowing what depth we are at. Common incisions and their layers, superficial to deep are listed next.

Laparatomy (flank incision): 1. skin; 2. subcutaneous tissue; 3. EAO m.; 4. IAO m.; 5. TA m. (its dorsal aponeurosis in ruminants) to include transversalis fascia; 6. Retroperitoneal fat if present; 7. Peritoneum

Ventral midline (linea alba) celiotomy: 1. skin; 2. subcutaneous tissue; 3. linea alba; 4. Retroperitoneal fat; 5. Peritoneum

Ventral paramedian celiotomy: 1. skin; 2. subcutaneous tissue; 3. External rectus sheath; 4. RA m.; 5. Internal rectus sheath; 6. Retroperitoneal fat; 7. Peritoneum

Clinical relevance and clinical application Q3:

Q3: You operated on a colicking llama 5 days ago and have to go back in because of persistent postoperative colic. The ventral midline incision of the first surgery has become infected (do you get the impression this case is not going so well? These cases keep you humble and test your mettle for sure). To avoid the contaminated midline incision site at the second surgery, you chose to do a ventral paramedian incision, i.e. parallel to and about 6 cm to the side of midline.

What is the 4th layer of tissue you expect to incise through on your way to the peritoneal cavity and a potentially grim looking abdomen?

- Abdominal wall muscles, linea alba and rectus sheaths. 6

Inguinal canal

The following is the same description provided at the start of the carnivore abdominal wall section.

The inguinal canal (left and right canals are present) is a passageway, a fissure, through the abdominal wall muscles, for nerves, vessels, and genital tissues (sex dependent) to pass through, in leaving or entering the abdominal cavity. The canal is entered or exited internally (i.e. on the inner surface of the abdominal wall) at the deep inguinal ring. Externally, on the outer surface of the abdominal wall, the canal is entered or exited at the superficial inguinal ring. The superficial inguinal ring is a slit in the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique m. We will study these structures in detail later and for now our goal is to avoid their disruption while dissecting the abdominal wall muscles. Look at the diagram and image below to help envision where the superficial inguinal rings are located in the inguinal region of the cadaver. The superficial inguinal ring is typically indistinct at this point in the dissection because it is covered by layers of fascia.

Observe: Examine the ungulate cadavers and determine the location of the superficial inguinal ring on the left side.

- Boundaries of the superficial inguinal ring, lateral view, and deep inguinal ring, medial view, in the horse. 5

- The abdominal muscles and their skeletal attachments. 8

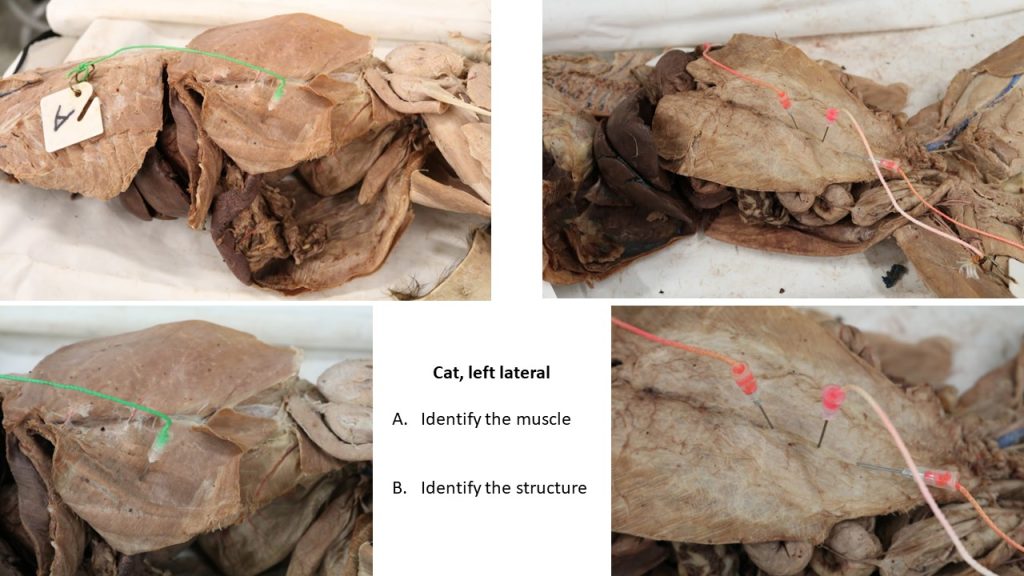

Gallery

Horse abdominal wall muscles

Goat abdominal wall muscles

Calf abdominal wall muscles

Pig abdominal wall muscles

Review Videos

Cat abdominal wall muscles – watch until 12 min

Dog abdominal wall muscles – 5 min, watch until 7 min

Cow abdominal wall layers at necropsy – 1 min, fresh tissue

Terms

| Abdominal Muscles | |

| External abdominal oblique m. | |

| Internal abdominal oblique m. | |

| Transversus abdominis m. or Transverse abdominal m. | |

| Rectus abdominis m. | |

| Abdominal wall/muscle structures | |

| Linea alba | |

| External rectus sheath | |

| Internal rectus sheath | |

| Superficial inguinal ring | |

| Inguinal canal | define (dissected later) |

| Deep inguinal ring | not identified yet, understand as part of inguinal canal anatomy |

| Flank | Ruminant, horse |

| Paralumbar fossa | Ruminant, horse |

| Lumbar vertebrae | All, note number and that L1, L6 in live ox are typically not palpable. |

| Subiliac lymph nodes | Ungulates only |

| Elastic abdominal tunic | Horse, ruminant – yellowish appearance |

| Deep circumflex iliac vessels | Horse flank |