MSK LAB 12A – Neck and Back: Muscles and Ligaments

Learning Objectives

- Identify the serratus dorsalis muscles.

- Identify epaxial muscle groups and cervical hypaxial muscles across the comparative species studied.

- Name the basic attachments and actions of the epaxial and cervical hypaxial mm.

- Identify the splenius m.

- Identify the nuchal ligament in the dog, horse, ruminant.

- Know/identify the associated nuchal ligament bursae in the horse.

- Identify important muscles of the poll region of the horse and ruminant.

- Connect anatomy to clinical relevance.

Lab Introduction:

Muscles and ligaments that form the neck and back region of the axial skeleton will be considered in this lab. As a unit, these muscles arch (flex or dorsiflex) and dip (extend or ventriflex) the back and curve (bend) the neck and back to one side or the other. Extending onto the tail, the muscles provide for the myriad directions that a tail can move or be held in one position. Intramuscular injections (e.g. in the neck of ungulates, lumbar area of dogs) are performed in specific regions of these axial muscles.

Dissection of muscles will continue on the left side of the carnivore cadaver. Please refer to prosected ungulate cadavers, and in general, to wet and dry lab specimens of various species to learn the anatomy.

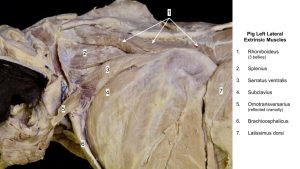

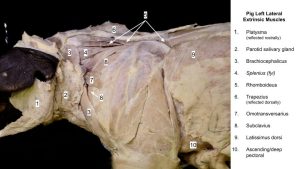

Dissect: Use the left side of the cadaver to dissect the muscles of the back and neck. To view the muscles of the back, perform an amputation of the left thoracic limb by transecting all of the thoracic limb extrinsic muscles.

Can you name the extrinsic muscles of the thoracic limb? (go back to Section 1: Thoracic Limb; Lab 3A, or read down a little further, if needed:))

The amputated limb may be disposed of, or stored in the cadaver bag for future reference.

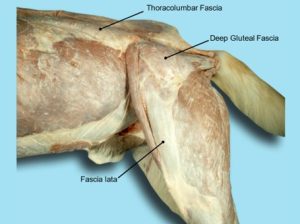

The deep fascia of the trunk, the thoracolumbar fascia (previously considered in the thoracic limb section), is attached to the spinous and transverse processes of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae. From its dorsal attachment to the spinous processes and the supraspinous ligament, it passes over the epaxial musculature to the lateral thoracic and abdominal walls, where it serves as origin for several muscles. On each side this fascia closely covers the abdominal muscles and contributes to the linea alba on the ventral midline (to be considered in future labs).

Dissect: Dissect caudally over the dorsal back and pelvic region, remove any areolar tissue (often has fat tissue within it) and the superficial fascia. The stumps of extrinsic muscle attachments to the axial skeleton should now also be removed to facilitate dissection of the back and neck muscles, that lie at a deeper level. Start with excising (and discarding) the latissimus dorsi m. from its rib and thoracolumbar fascia attachments. Then excise the serratus ventralis, rhomboideus, trapezius, omotransversarius and brachiocephalicus stumps (the pectoral muscle stumps are generally not in the way of the neck and back dissection).

The muscles of the back and neck, or axial muscles, are classified morphologically into epaxial and hypaxial groups. The epaxial muscles lie dorsal to the transverse processes of the vertebrae and function mainly as extensors of the vertebral column. The hypaxial group embraces all other back and neck muscles not included in the epaxial division. These muscles are located ventral to the transverse processes of the vertebrae and include those of the abdominal and thoracic walls.

Dissect: Transect and reflect (or excise) the thoracolumbar fascia so as to observe the underlying epaxial muscles. In the lumbar region the muscle systems are mostly fused side by side systems and cleanly separating them is not possible or required.

- Dog thoracolumbar fascia. 40

- Cat thoracolumbar fascia. 40

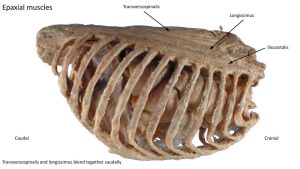

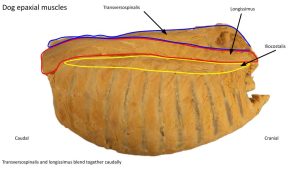

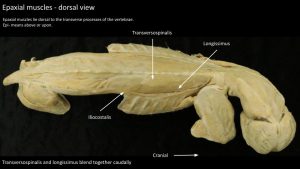

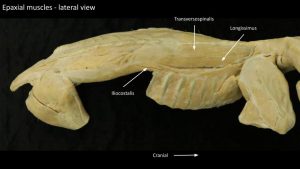

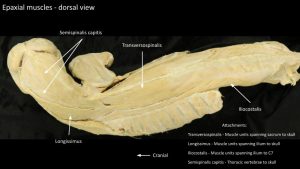

Epaxial muscles

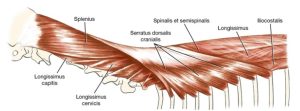

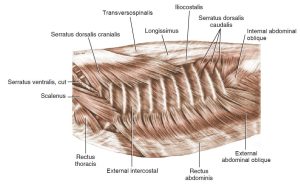

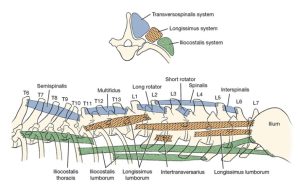

The epaxial muscles are associated with the vertebral column and ribs and most of them fit into one of three (3) major parallel longitudinal muscle systems, located on each side of midline. Each muscle mass is composed of many overlapping fascicles. The three systems are the iliocostalis system, the longissimus system, and the transversospinalis system. Fusions occur between these systems giving rise to varying muscle patterns that are difficult to separate. These muscles act as extensors of the vertebral column and produce lateral movements of the trunk when contracting on one side. FYI – the m. erector spinae (a term often used in reference to nerve blocks along the back) refers to the collective iliocostalis system, the longissimus system and a few independent spinal muscles.

Dissect: Dissect and identify the three (3) major epaxial muscle systems as described below.

Note: with the exception of semispinalis capitis m. (part of the transversospinalis system), you are responsible for knowing the epaxial muscles at the system level only (i.e. no need to learn individual parts).

Iliocostalis System: the lateral unit

Dissect: As needed, further transect and reflect (or excise and discard) the thoracolumbar fascia and any fat to expose the glistening aponeurosis of the epaxial muscles. In the lumbar region the iliocostalis and longissimus systems are mostly fused side by side systems and cleanly separating them is not possible or required. Identify and reflect ventrally the muscle leaves of the small serratus dorsalis caudalis m. (a muscle of expiration) to fully view the iliocostalis system. We will reconsider this respiratory muscle in the thoracic wall section.

- The iliocostalis lumborum arises from the crest of the wing of the ilium in common with the longissimus lumborum and inserts on the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae and the last four or five ribs.

Dissect: Moving cranially, identify and reflect ventrally the serratus dorsalis cranialis m. (we will return to this muscle in the thoracic wall section) to expose the iliocostalis muscles as they insert on the dorsal aspect of the ribs. This section of the iliocostalis system is readily separated from the adjacent longissimus system.

- The iliocostalis thoracis is a long, narrow muscle mass extending from the twelfth rib to the transverse process of the seventh cervical vertebra. Individual components of the muscle extend between and overlap the ribs.

Observe: Identify the iliocostalis muscle system as a whole and know the general attachments thereof.

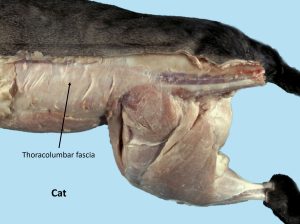

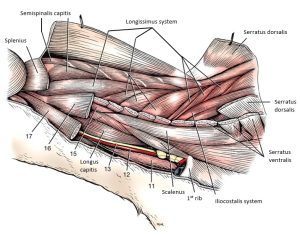

- Topography of the mm. splenius and serratus dorsalis cranialis. 1

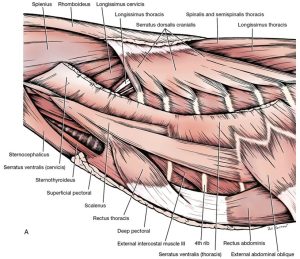

- Superficial muscles of thoracic cage, lateral aspect. 3

- Deep muscles of the dog neck, left side. 1

- Transverse (top) and left lateral (bottom) schema of the epaxial muscle systems.1

- Dog thoracic wall muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

Longissimus system: the intermediate unit

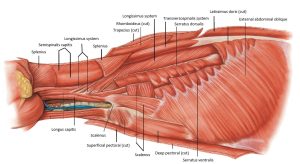

The longissimus is the intermediate or middle portion of the epaxial musculature. Lying dorsomedial to the iliocostalis system and ventrolateral to the transversospinalis system, its overlapping fascicles extend from the ilium to the head. It consists of three major regional divisions: thoracolumbar, cervical, and capital.

- The longissimus thoracis et lumborum arises from the crest and medial surface of the wing of the ilium and, by means of an aponeurosis, from the supraspinous ligament and the spines of the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae. Its fibers course craniolaterally. As previously noted, this part of the longissimus system fuses substantially with the iliocostalis lumbar division. This division of the longissimus inserts on various processes of the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae. The thoracic portion may be seen inserting on the ribs and the seventh cervical vertebra, just medial to the iliocostalis thoracis.

- The longissimus cervicis, the cranial continuation of the longissimus muscle into the neck, consists of four fascicles arranged so that the caudal fascicles partially cover those that lie directly cranioventral to them. They lie in the angle between the cervical and thoracic vertebrae and insert on the transverse processes of the last few cervical vertebrae.

- The longissimus capitis is a distinct muscle medial to the longissimus cervicis and splenius muscles. It extends from the first three thoracic vertebrae to the mastoid part of the temporal bone. It is firmly united with the splenius as it passes over the wing of the atlas to its insertion.

Dissect: Using blunt dissection, separate the longissimus system from its lateral and medial neighboring systems, where obvious fascial planes exist to do so. Don’t attempt to create muscle system divisions where the systems are fused between each other. Identify the longissimus muscle system as a whole and know the general attachments thereof (see muscle chart).

- Topography of the mm. splenius and serratus dorsalis cranialis. 1

- Superficial muscles of thoracic cage, lateral aspect. 3

- Muscles of neck and thorax, lateral view. 1

- Deep muscles of the dog neck, left side. 1

- Transverse (top) and left lateral (bottom) schema of the epaxial muscle systems.1

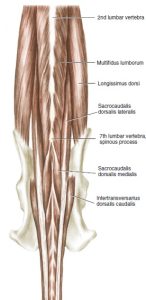

- Muscles of lumbocaudal region, Epaxial muscles, dorsal aspect. 3

- Deeper muscles of the cat in lateral view. 5

- Superficial musculature of the neck and thorax of the cat with thoracic limb removed, lateral view. 4

- Dog thoracic wall muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

Transversospinalis system: the medial unit

The transversospinalis system, the most dorsomedial and deep epaxial muscle mass, consists of different groups of muscles that join one vertebra with another or span one or more vertebrae. This complex system extends from the sacrum to the head. Included are muscles whose names depict their attachments or the functions of their fascicles: spinalis, semispinalis, multifidus, rotatores, interspinalis, and intertransversarius.

Clinical relevance: laminectomy; possible origin of back pain.

Transversospinalis system muscles must be reflected to perform a laminectomy (i.e. the removal of a lamina of a vertebral body, or a few in a row, to access the vertebral canal). Take a second look at these muscles – in the Nervous System dissection there is an opportunity to perform a laminectomy.

Dissect: Use blunt dissection to separate between the longissimus and transversospinalis systems, up to the point of the mid thorax for now. Before we complete our identification of the T. system we need to recognize an interloper…..scroll on down…..

- Superficial muscles of thoracic cage, lateral aspect. 3

- Topography of the mm. splenius and serratus dorsalis cranialis. 1

- Muscles of neck and thorax, lateral view. 1

- Transverse (top) and left lateral (bottom) schema of the epaxial muscle systems.1

- Superficial musculature of the neck and thorax of the cat with thoracic limb removed, lateral view. 4

- Dog thoracic wall muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

- Dog epaxial muscles

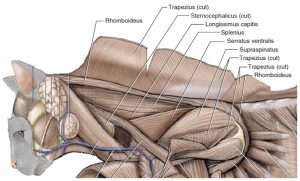

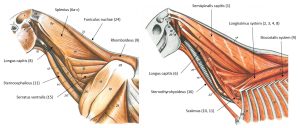

Splenius m.

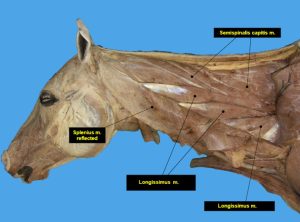

The splenius m. (with one belly in carnivores, and two in ungulates) is a rather large muscle on the dorsolateral surface of the neck, deep to the rhomboideus m. and the serratus dorsalis cranialis. The splenius m. does not belong to an epaxial muscle system, but it is located in the same area, lying superficial to transversospinalis mm., and hence it is dissected and identified at this juncture. Its fibers extend in a slightly cranioventral direction from the third thoracic vertebra to the skull. The muscle arises from the cranial border of the thoracolumbar fascia, the spines of the first three thoracic vertebrae, and the dorsal fibrous midline (median raphe) of the neck. It inserts on the nuchal crest and mastoid part of the temporal bone.

Note: “Raphe” [Gr] = a stitching or seam. A raphe is typically a midline seam where tissues from opposite sides meet (eg skin, muscle). The median raphe of the neck is a longitudinal fibrous septum between right and left epaxial muscles dorsal to the nuchal ligament. It serves as the attachment for many of the cervical muscles, and some of the extrinsic muscles of the thoracic limb.

Dissect: Identify the splenius muscle. Undermine and then transect the splenius ~2 cm caudal to its insertion on the nuchal crest and reflect the muscle mass dorsally to its median raphe attachment. Clean muscle margins and remove fascia to isolate and identify the semispinalis capitis m., lying deep to the splenius.

- Topography of the mm. splenius and serratus dorsalis cranialis. 1

- Muscles of neck and thorax, lateral view. 1

- Deeper muscles of the cat in lateral view. 5

- Superficial musculature of the neck and thorax of the cat with thoracic limb removed, lateral view. 4

- Dog thoracic wall

Interactive review content:

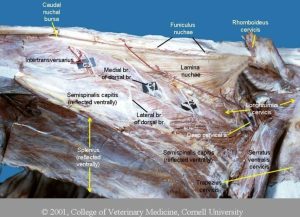

Semispinalis capitis m.

The semispinalis capitis m. is a member of the cervical portion of the transversospinalis system. It extends from the thoracic vertebrae to the head. It has two parts, m. complexus and m. biventer cervicis.

Observe: Now identify the transversospinalis muscle system as a whole and know the general attachments thereof (see muscle chart).

- Deep muscles of the dog neck, left side. 1

- Superficial musculature of the neck and thorax of the cat with thoracic limb removed, lateral view. 4

- Dog neck muscles

Nuchal ligament

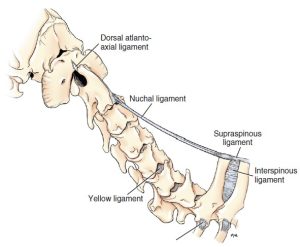

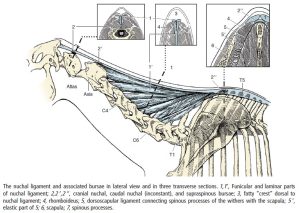

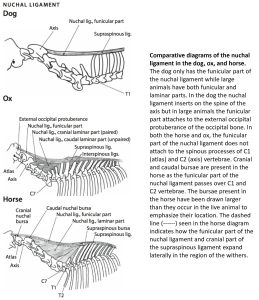

Found in the canine, and certain ungulates (see later), the nuchal ligament is a laterally compressed, paired, yellow, elastic band or cord-shaped structure, lying between the medial surfaces of the left and right semispinalis capitis muscles. ‘Nucha’ refers to the back or nape of the neck. This long elastic ligament functions as passive suspension support of the neck and head and aids in raising the head from the ground (think grazing ungulates lifting their heads). In the canine, this ligament extends from the spinous process of the first thoracic vertebra to the spine of the axis (C2). There are two parts to the nuchal ligament described, a funicular and a laminar part. The dog has the funicular part only. To confirm your suspicion at this time….yes, the cat does NOT possess a nuchal ligament, nor does the pig.

Dissect: In the canine cadaver, return to the semispinalis capitis muscle and separate its two subparts to make a window for viewing and identification of the nuchal ligament. The pale yellow band of tissue is unmistakable on midline, once located.

Continuing caudally from the nuchal ligament of the neck region, the supraspinous ligament connects the dorsal aspects of all vertebral spines from T1 vertebra through to the sacral vertebrae. The ligament passes from one spinous process tip to another.

- Ligaments of the cervical region of the dog. 3

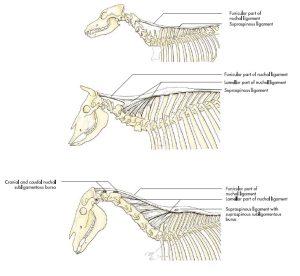

- Nuchal and supraspinous ligament of the dog, ox and horse. 7

- Dog neck muscles

Hypaxial muscles

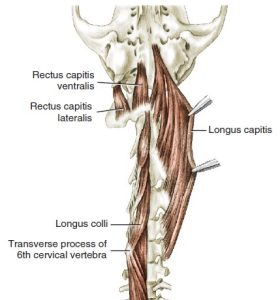

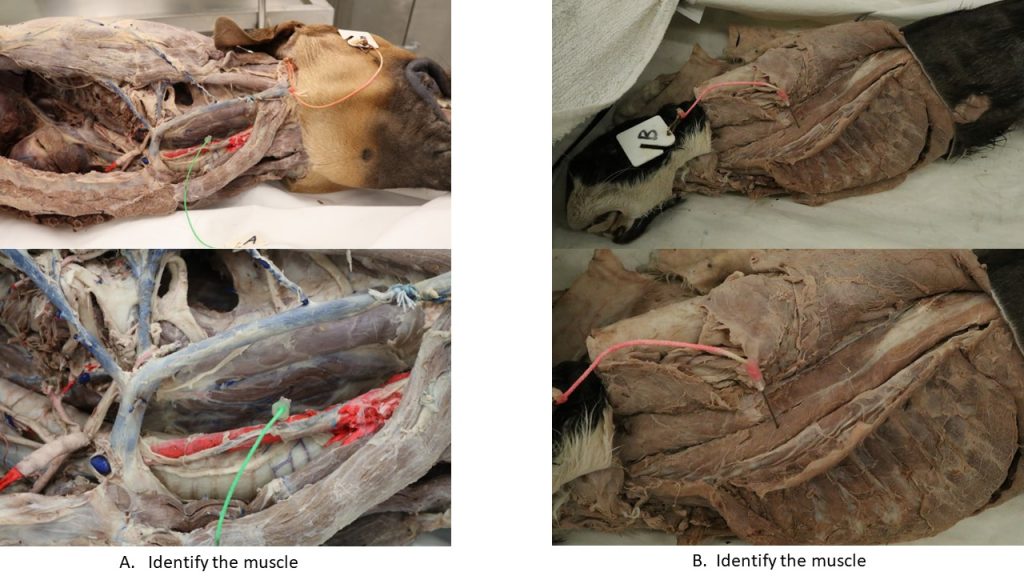

Two hypaxial muscles of the neck region are of interest at this time, the longus capitis m. and the longus colli m. The longus capitis m. lies on the lateral surface of the cervical vertebrae, lateral to the longus colli m. The longus capitis m. arises from the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae and inserts on the muscular tubercle on the ventral surface of the basioccipital bone of the skull. This muscles acts to flex the atlanto-occipital joint, and draw the neck down.

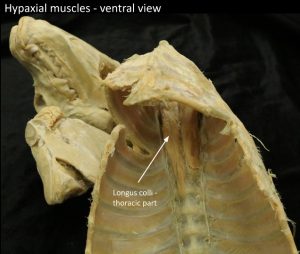

The longus colli m. covers the ventral surfaces of the vertebral bodies from the sixth thoracic vertebra (we will see this muscle in the thorax too!) cranially to the atlas (C1). It consists of many overlapping fascicles that attach to the vertebral bodies or the transverse processes. The most cranial cervical bundles attach to the atlas. This muscles acts to flex the neck.

Dissect: To expose these hypaxial muscles in the neck region, bluntly dissect fascia away from the lateral side near the trachea to expose a path towards the deeper ventral neck region. Extend this dissection cranially and caudally along the tracheal margin so that the trachea and esophagus and other soft tissues can be readily retracted to the opposite side of the dissection to view the hypaxial mm. related to the ventral midline. Clean away fascia lying on the surface of the muscles to more clearly identify the left and right pairs of muscles. Slide your finger along the longus colli m. caudally – you may enter the thoracic inlet and palpate the thoracic part of the muscle (to be seen when the thorax is opened in a later unit). Be sure to identify these muscles on plastinated models as well, where their extent and relationships are clearly appreciated.

Clinical relevance: surgical access to the ventral surface of the cervical vertebrae and column.

- Ventral muscles of the dog vertebral column. 3

- Deep muscles of the dog neck, left side. 1

- Dog hypaxial mm.

- Dog hypaxial mm.

- Dog hypaxial mm.

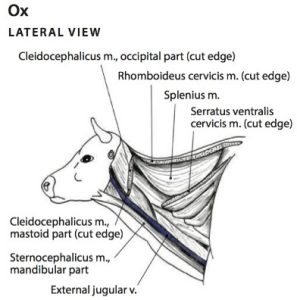

Ungulate neck and back comparative anatomy

Observe: Refer to the prosected ungulate cadavers to identify and consider the following comparative anatomy features. A check list of ungulate anatomy terms is available at the end of this section, combined with the terms for carnivores.

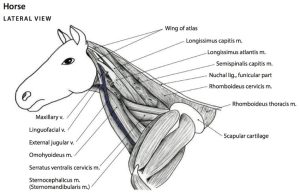

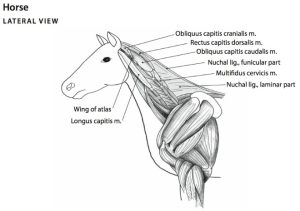

Splenius m.

The splenius m. is a large muscle of the dorsolateral neck. The splenius m. has a capitis (dorsal) and cervicis (ventral) part in ungulates, unlike the carnivore which has the capitis belly only. In the pig, the splenius broadens cranially to insert as three digitations (two on the skull, one on the atlas) making it appear to have three bellies.

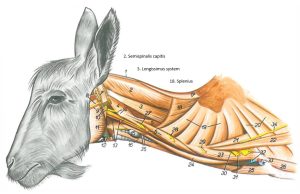

- Superficial and deeper muscles of the horse neck, left view. 11

- Deeper muscles of the cow neck. 13

- Deep muscles of the neck of the goat. 11

- Deeper muscles of the neck of the pig. 8

- Horse neck

- Horse splenius 40

- Calf neck

- Pig shoulder

- Pig shoulder

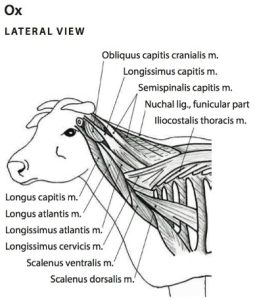

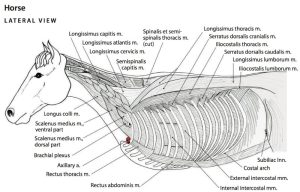

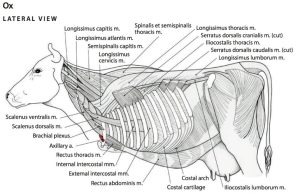

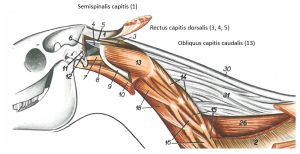

Epaxial muscles

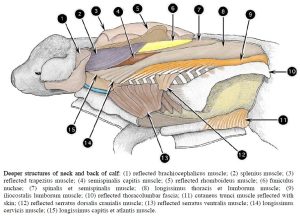

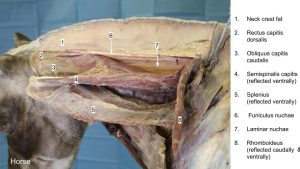

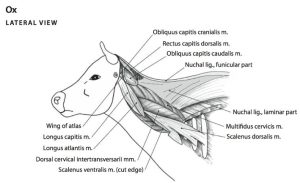

The segmented longissimus muscles constitute the longest muscle system in the body, extending from the ilium to the head. In the ungulates, the most cranial division is divided into two components, the longissimus capitis, which extends to the head, and the longissimus atlantis, which terminates on the wing of the atlas. The longissimus cervicis attaches to the transverse processes of the other cervical vertebrae. The iliocostalis and transversospinalis systems are similar to the carnivore. The semispinalis capitis m. is a cervical part of the transversospinalis system.

Observe: Refer to the prosected ungulate cadavers to learn the epaxial muscles as units and do not be concerned with knowing names of their specific subparts, except the semispinalis capitis m..

Clinical relevance: possible source of back pain; surgical approaches to the vertebral column.

The epaxial mm. function to extend and laterally move the vertebral column and strain/soreness of these muscles can be a cause of lameness. A dorsal surgical approach to the cervical vertebrae is used when treating “Wobbler syndrome” in large breed dogs (to perform a dorsal laminectomy). The similar condition in horses (Cervical Vertebral Compressive Myelopathy) is most commonly treated via a ventral approach to the cervical vertebrae (partly for practical reasons) and using a different surgical technique (interbody fusion). See hypaxial muscles below.

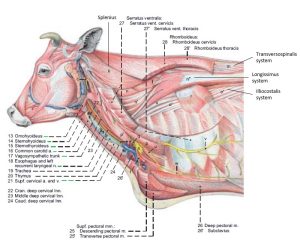

- Deeper structures of neck and back of calf. 2

- Deeper muscles of the neck of the horse, lateral view. 6

- Deeper muscles of the neck of the ox, lateral view. 6

- Deepest muscles of the neck of the ox, lateral view. 6

- Thoracic wall and select axial muscles of the horse. The thoracic limb and serratus ventralis thoracis muscle have been removed. 6

- Thoracic wall and select axial muscles of the ox. The thoracic limb and serratus ventralis thoracis muscle have been removed. 6

- Horse semispinalis capitis 40

Nuchal ligament

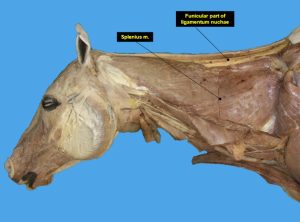

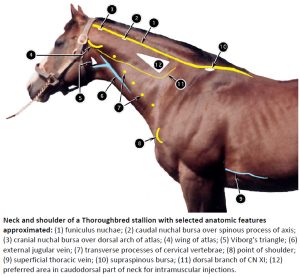

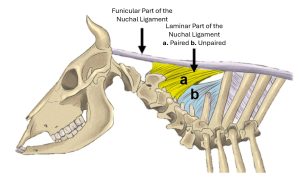

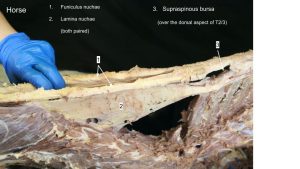

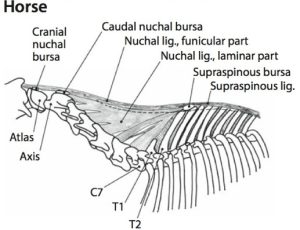

The nuchal ligament has a funicular part and a laminar part in the horse and ruminant. It is a more extensive and complex structure in these relatively long-necked animals, compared to the dog, with only the funicular part present. This ligament is NOT present in the pig.

In the horse, the paired funiculus nuchae (i.e. nuchal ligament, funicular part) begins as a cranial continuation of the supraspinous ligament at T3/T4. The paired funiculus nuchae of the ruminant originates further caudally, where it partially covers the epaxial muscles. The funicular part of the equine and ruminant nuchal ligament continues cranially to attach on the skull at the external occipital protuberance (in the dog, this part ends on C2). The paired lamina nuchae is the sheet-like part that extends ventrally from the funicular part, to attach on cervical vertebrae C2-C7. In the ruminant there is an additional, caudally located, unpaired lamina nuchae.

Clinical relevance: suspension support of neck.

Important elastic structure providing passive suspension support of the head and neck and aiding in elevating the head and neck from a lowered position (e.g. when grazing).

Observe: Identify the nuchal ligament structures in the horse and ruminant by reflecting the overlying neck muscles. This is a midline structure, so from a lateral approach it is a deeply located tissue.

- Neck and shoulder of a Thoroughbred stallion with selected anatomic features approximated. 2

- Equine nuchal ligament, Cornell University.

- Horse nuchal ligament. 8

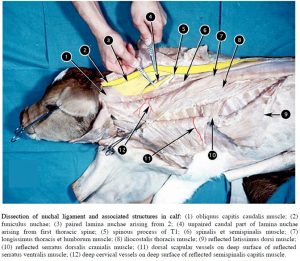

- Dissection of nuchal ligament and associated structures in calf. 2

- Comparative diagrams of the nuchal ligament in the dog, ox, and horse. 6

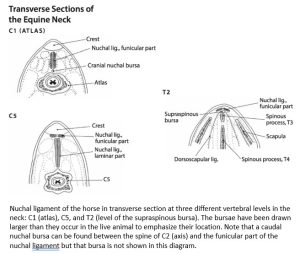

- Nuchal ligament of the horse in transverse section at three different vertebral levels in the neck. 5

- Cow nuchal ligament A. Hartzheim

- Horse neck

- Horse neck

- Horse neck

- Horse neck

- Calf neck

- Calf neck

- Calf neck

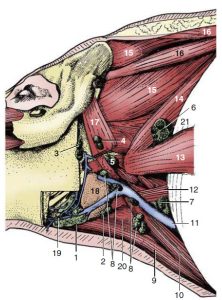

Nuchal bursae – Horse only

Horse only: The horse has 2-3 bursae associated with the funiculus nuchae: the cranial nuchal bursa and caudal nuchal bursa at C1 and C2 respectively, and a supraspinous bursa at the level of T2/T3. The cranial and caudal nuchal bursae are very difficult to find and we won’t dissect these, and the caudal nuchal bursa is variably present anyway. The supraspinous bursa is sometimes identifiable and we will have a go at finding it.

Observe: Refer to the below diagram to understand the location of all the nuchal bursae in the horse and review the prosected cadaver to identify the supraspinous bursa specifically. It won’t be an overly inspiring bursa to view but its clinical significance can be substantial. Appendix on synovial structures.

Clinical relevance: bursitis – fistulous withers and poll evil!

Atlanto-occipital (poll) region

Horse and Ruminant

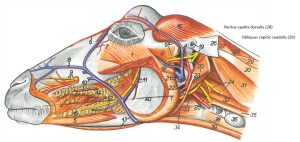

The ‘poll’ region of the ungulate is located dorsally, at the caudal extent of the skull, between, or just behind the level of the ears. Movement of the poll occurs primarily at the first two vertebral column joints. The atlanto-occipital joint is designed to allow for extension/flexion of the skull on the atlas, the so-called “yes joint.” The atlantoaxial joint is a unique intervertebral joint that allows for rotation around the dens, the so-called “no joint”. The wing of the atlas is a critical, externally-palpable landmark of the poll region. Numerous muscles attach in the poll region and have actions on the joints. Two muscles we wish to consider are the obliquus capitis caudalis m. (attaches axis to atlas) and the rectus capitis dorsalis mm. (FYI, has major and minor parts). The nuchal ligament is also an important structure of the region.

Observe: Refer to skeletons and review the atlanto-occipital and atlantoaxial joints. Then examine a prosected horse and ruminant cadaver. Reflect the transected funiculus nuchae cranially to aid in exposing the underlying dorsal muscles of the neck of the poll region. The rectus capitis dorsalis mm. lie deep to the nuchal ligament. The obliquus capitis caudalis m. is relatively large and located laterally between the axis and the atlas.

Recall, in the horse, that the cranial (consistently present) and caudal (inconsistently present) nuchal bursae lie over C1 and C2 respectively and that there are no bursae in the ruminant. Infection of these cranial and caudal nuchal bursae (bursitis) is referred to as “poll evil”.

Clinical relevance: poll region pathology

- Horse, deep muscles of the neck. 11

- Nuchal ligament and deepest muscles of the neck of the horse, lateral view. 6

- Nuchal ligament and deepest muscles of the neck of the ox, lateral view. 6

- Goat neck muscles. 11

- Horse neck

- Horse neck

Hypaxial muscles

As for the carnivore, two hypaxial muscles of the neck, the longus capitis m. and the longus colli m. are of interest. The longus capitis m. lies on the lateral surface of the cervical vertebrae, lateral to the longus colli m. The longus capitis m. arises from the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae and inserts on the muscular tubercle on the ventral surface of the basioccipital bone of the skull. This muscles acts to flex the atlanto-occipital joint, and draw the neck down.

The longus colli m. covers the ventral surfaces of the vertebral bodies from the sixth thoracic vertebra (we will see this muscle in the thorax too!) cranially to the atlas (C1). It consists of many overlapping fascicles that attach to the vertebral bodies or the transverse processes. The most cranial cervical bundles attach to the atlas. This muscle acts to flex the neck.

Observe: Refer to the prosected horse and ruminant cadavers. Retract the ventral neck viscera (trachea, esophagus) to view the longus colli m lying against the cervical vertebrae. The longus capitis m. may be viewed from a lateral or ventral perspective.

Clinical relevance: surgical access to the ventral surface of the cervical vertebral column; longus capitis m. – avulsion fractures at base of skull; relationship to guttural pouch in the horse.

- Thoracic wall and select axial muscles of the horse. The thoracic limb and serratus ventralis thoracis muscle have been removed. 6

- Superficial and deeper muscles of the horse neck, left view. 11

- Thoracic wall and select axial muscles of the ox. The thoracic limb and serratus ventralis thoracis muscle have been removed. 6

Review Videos

Goat neck muscles – 3 min

Goat epaxial muscles – 1 min

*At 13:45, Dr. G misspoke, saying that ruminants have an unpaired funicular nuchae. What she meant to say was that they have an unpaired LAMINAR nuchae.

Ox vertebrae and calf neck muscles from a dorsal view – watch until 5 min

Ignore the discussion of the dorsal atlantooccipital membrane – we will cover that in the nervous system unit.

Calf epaxial muscles – 3 min Horse neck muscles – 2 min, watch until 7 min

Horse nuchal ligament in motion – 15 sec

Horse epaxial muscles – 30 seconds

Terms

|

Muscles/structures |

||

| Epaxial mm. | Iliocostalis system | |

| Longissimus system | ||

| Transversospinalis system | ||

| Semispinalis capitis m. | Carnivore, horse, ruminant | |

| Splenius | all; has 2 parts in ungulates | |

| Hypaxial mm. | Longus capitis m. | |

| Longus colli m. | ||

| Nuchal ligament | Funiculus nuchae | Dog, horse, ruminant |

| Lamina nuchae (paired) | Horse, ruminant | |

| Lamina nuchae (un-paired) | Ruminant – identify in calf | |

| Bursa | Supraspinous bursa | Horse – often hard to specifically identify but let’s have a good crack at it. |

| Cranial (and caudal if present) nuchal bursa | Horse – don’t look for these but be aware of location | |

| Rectus capitis dorsalis mm. | Horse, ruminant | |

| Obliquus capitis caudalis m. | Horse, ruminant | |

|

Muscle attachments and actions |

||

| Muscle/structure | Attachments | Action |

| Iliocostalis system | Overlapping fascicles from ilium to rib 1 | Extension and lateral movement of vertebral column |

| Longissimus system | Overlapping fascicles from ilium to skull | Extension and lateral movement of vertebral column |

| Transversospinalis system | Overlapping fascicles from sacrum to skull | Extension and lateral movement of vertebral column |

| Semispinalis capitis | Thoracic vertebrae to skull | Extend head and neck, lateral flexion of neck |

| Splenius | Spinous processes T1‐3 and median raphe to skull | Extend and raise head and neck, lateral flexion of neck |

| Longus colli | Ventral vertebral bodies and transverse processes T6 to C1 | Flex neck |

| Longus capitis | Transverse processes cervical vertebrae to skull | Flex atlanto‐occipital joint and draw neck ventrally |