MSK LAB 23A – The Ungulate Foot – based on equine model

Learning Objectives

- Recognise what is defined as the equine ‘foot’

- Identify the anatomy of the epidermal structure of the foot (hoof capsule)

- Identify the anatomy of the dermal structures of the foot

- Understand how the dermal and epidermal components bond together.

- Have an appreciation for foot conditions that occur when the hoof wall/dermal bond becomes diseased or fails (e.g. laminitis).

Lab instructions:

Dissection of the foot is not required. Use the wet and dry prosections and plastinated specimens to come to grips with the foot anatomy. Have the specimens laid out in front of you so you can refer to all structures and match parts to parts. Start with the hoof (the epidermal part of the foot) and then move on to the dermal structures of the foot attached to the digit. Identify the bolded structures as you study this section. External (epidermal) foot structures may also be studied on the dissected limbs from LAB 21A.

The equine ‘foot’

[The following is a summarized description of the detail provided in Dr. Smallwood’s ‘Guide’. If you can take the time and wish to explore this anatomy in greater depth, start by reading Smallwood’s ‘Guide’ pp 365-376 – there are copies in the lab and the library.]

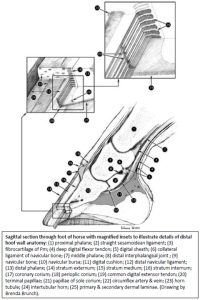

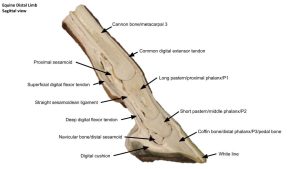

The term “equine foot,” is used to describe the epidermal hoof (aka hoof capsule) and all structures contained therein (e.g., bones, tendons, ligaments, vessels). The horse not only supports its entire weight, but also can withstand the tremendous forces generated by locomotion, while hanging from the inside of what amounts to two fingernails and two toenails.

Hoof

The hoof is composed of a modified epidermis known as horn or hard keratin, as opposed to the soft keratin of skin. The junction of hoof and skin is termed the coronet, the line where hair meets epidermal horn. Around this junction are specialized transitional cells that produce a soft, flaky horn known as periople. The periople is homologous to the cuticle of your fingernail and, as such, extends visibly a variable distance down the hoof wall (typically about 1 cm), and widens over the bulbs of the heel. As the major part of the hoof wall grows distally, under the periople, a thin waxy coat is pulled off the deep surface of the periople. This thin outermost layer of the hoof wall, also known as the stratum externum, accounts for the natural sheen or glossy appearance of the hoof wall. It is the natural hoof dressing and functions as an important moisture barrier. Stratum externum is synonymous with periople.

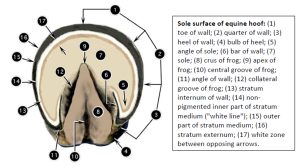

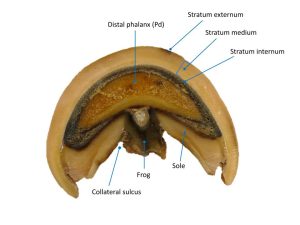

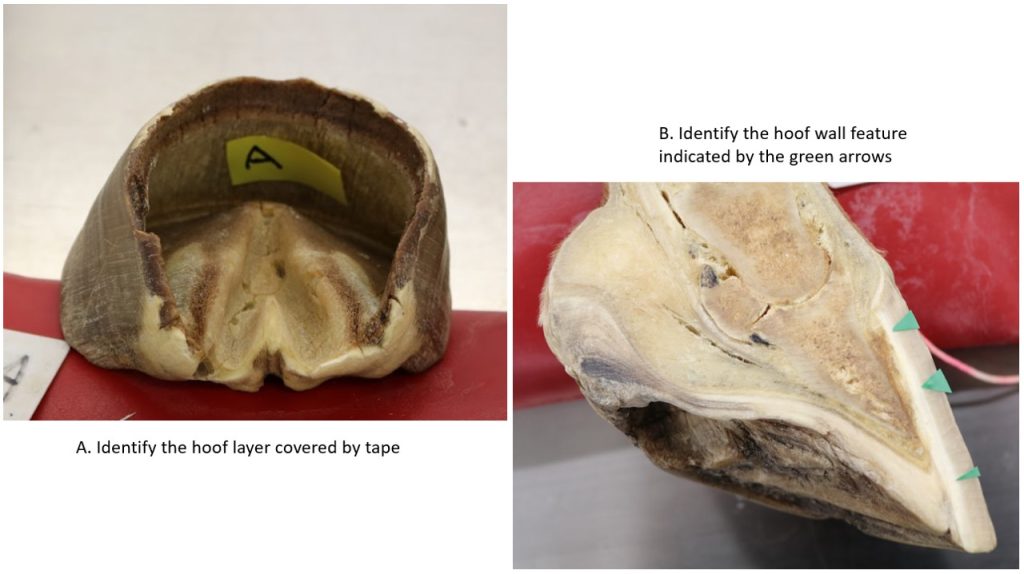

The hoof wall is divided into the following regions: (1) the toe (most dorsal 60° or so); (2) the quarters (next 30° or so medially and laterally); and (3) the heels (most palmar part of the wall). Now, turn the hoof over so that the sole surface can be seen. Here you can observe the distal (ground) surface of the wall, which is reflected at the angles of the wall as the bars. Thus, the bars are part of the hoof wall. Axial to the bars are deep grooves, the paracuneal or collateral grooves of the frog.

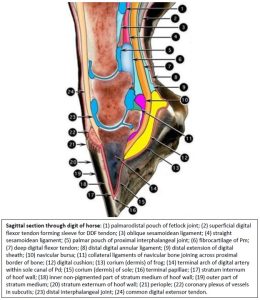

- Sagittal section through digit of horse. 2

- Sole surface of horse hoof. 2

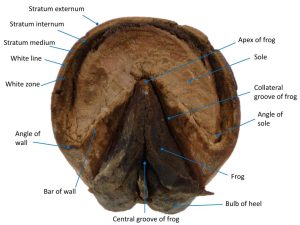

- Horse hoof

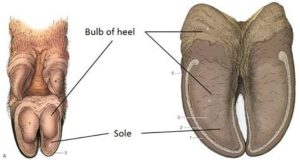

The heel bulbs are continued as the two crura of the frog, which narrow and converge dorsally to the apex of the frog. A central groove (sulcus) of the frog separates the two crura. Most of the ground surface of the hoof forms the sole. The sole is normally concave, and for the most part it is non-weight-bearing. The horn of the sole is softer than that of the wall, and that of the frog is even softer than that of the sole. Although the frog becomes hardened on dried specimens, the frog of the living animal is resilient to compression.

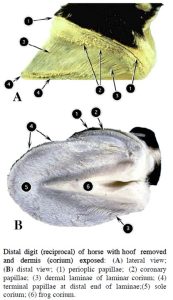

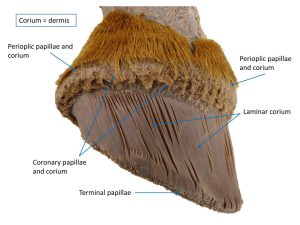

Observe: As you examine the inner surface of the hoof wall, ideally have its “reciprocal” next to it- that is, a specimen of the deeper tissues of the distal equine limb from which the hoof has been removed. This way you can correlate the anatomy of the hoof (epidermis) with that of the distal limb (covered by dermis). The two go together like hand in glove, and you can appreciate their interlocking relationship best by studying the two specimens together.

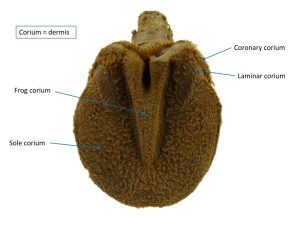

NOTE: corium is just another name for the dermis of the foot, and adjectives (e.g., perioplic, coronary, sole) are merely regional designations of this continuous layer of the integument.

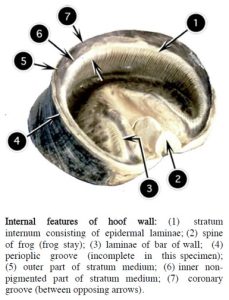

Observe: When you examine the inner surface of the hoof capsule, starting at the top edge, you should first locate a very, almost indiscernible, narrow groove just inside the proximal border of the hoof wall. This perioplic groove accommodates the perioplic corium (dermis) that nourishes the perioplic epithelium, which is the tissue that actually produces the periople.

Next, you should note the large groove that indents the proximal part of the wall. This is the coronary groove, which accommodates the coronary corium and a major vascular plexus, the coronary plexus.

- Internal features of hoof wall. 2

- Distal digit of horse with hoof removed and dermis exposed. 2

- Horse lamina

- Horse lamina

Over these papillae is the germinal epithelium that produces the tubular-shaped horn of the stratum medium and is responsible for most (>90%) of the hoof wall production. The stratum medium accounts for more than 80% of the hoof wall thickness.

Observe: Regardless of whether you have a dark or a relatively light hoof, you should note that the deeper part of the stratum medium is non-pigmented.

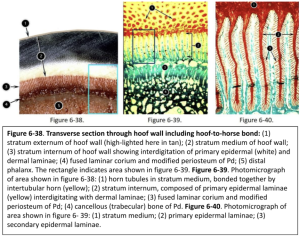

The deepest part of the hoof wall is characterized by many parallel laminae (lamellae), forming the stratum internum aka epidermal (insensitive) laminae.

This portion of the hoof wall is produced at the coronary region (like the stratum medium) by epithelium nourished by the coronary corium. These epidermal laminae interdigitate with the dermal (sensitive) laminae of the laminar corium. Note, the laminar corium is covered by and nourishes a germinal epithelium but this epithelium is not producing the epidermal laminae. There are about 600 primary laminae in each hoof of the horse. Approximately 100,000 microscopic secondary laminae arise from the sides of the 600 primary laminae creating a large surface area (~1 m2) that bonds the horse to the hoof.

Connective tissue fibers extend from the parietal-surface periosteum of the distal phalanx (Pd) through the secondary laminae to the basement membrane of the dermoepidermal junction, thus completing the bonding of the Pd to the hoof wall. It is the large surface area produced by the complex interdigitation of the laminae that allows the system to work; the horse depends on this bond to remain suspended from its hoof. This connection between bone and hoof wall is referred to as the suspensory apparatus of the distal phalanx. The horse is, in effect, hanging from the inside of its hoof wall, balanced across a total of four digits!

- Sagittal section through foot of horse with magnified insets to illustrate details of distal hoof wall anatomy.

- Sagittal section through digit of horse. 2

- Internal features of hoof wall. 2

- Distal digit of horse with hoof removed and dermis exposed. 2

Clinical relevance Q7:

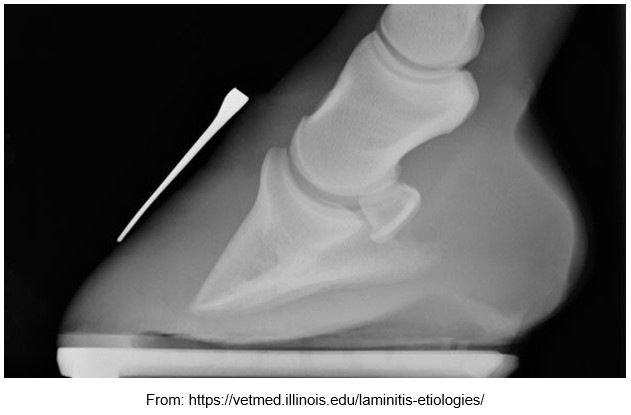

Laminitis (literally, inflammation of the sensitive laminae) can be considered the most devastating and serious of foot conditions in the horse. If the system completely breaks down, the inevitable occurs- that is, the horse ‘falls through’ the bottom of its hoof because it is no longer held suspended inside the hoof capsule.

Q7: Review the radiograph.

Normally the dorsal surface of the distal phalanx is parallel to the dorsal hoof wall.

What is evident in this radiograph?

Why has it occurred?

What is the metallic structure lying on the dorsal hoof wall?

Why was it positioned there before taking the radiograph?

Observe: Like that of the deeper part of the stratum medium, the horn of the stratum internum, which again note, is primarily produced in the coronary region, is non-pigmented, regardless of the outside pigmentation. On the inner surface of the hoof capsule, the sole has many openings, which receive the relatively short papillae of the sole corium.

The sole is produced by the germinal epithelium over the sole corium, and the horn of the sole contains about 33% water.

- Internal features of hoof wall. 2

- Distal digit of horse with hoof removed and dermis exposed. 2

- Sagittal section through foot of horse with magnified insets to illustrate details of distal hoof wall anatomy.

- Horse lamina

- Horse lamina

- Horse lamina

Observe: On the inner surface of the hoof capsule, the crura of the frog are obvious as depressions, and the central groove is represented by a prominent internal ridge- the spine, or frog stay.

The soft horn over the frog is produced by the germinal epithelium over the frog corium and is the softest horn of the hoof, containing about 50% water.

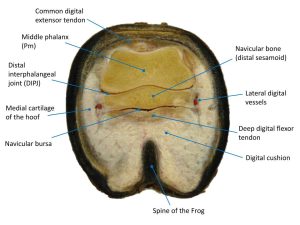

When you examine the reciprocal, you can see the bulges of the crura and the central groove that is occupied by the spine of the frog. The part of the foot that lies above the crura of the frog is occupied by a fibrofatty mass of tissue known as the digital cushion.

From this examination, we have learned that most of the hoof wall (i.e. stratum medium and stratum internum) is produced by the germinal epithelium that covers the coronary corium. From this region the horn of the hoof wall is produced at the rate of about 8 mm (~1/3 inch) per month. Thus, for the horn of the toe region to move from the coronet to the ground surface, where in the unshod state it is worn away at about the same rate, takes about 8 to 9 months. This is the approximate rate of hoof wall production in a mature horse; it appears to be greater in the young foal (~3 mm per week or 12 mm per month).

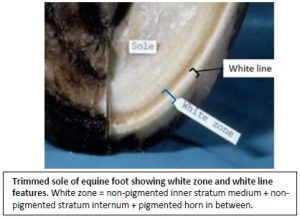

Now, what happens when the epidermal (insensitive) laminae of the wall are pushed downward to the level of the sole? What fills in between the epidermal laminae as they move beyond the dermal (sensitive) laminae? We can’t just leave gaps between them, because infection could enter the sensitive tissues of the foot. Solution: the distal ends of the dermal laminae form papillae, the terminal papillae. Like little “caulking guns,” the germinal epithelium over these terminal papillae produces a pigmented horn that fills in the gaps between the distally moving epidermal laminae. Thus, the total horn composite that moves distally from this region is an alternating pattern of pigmented horn (from the terminal papillae) and non-pigmented horn (continuation of epidermal laminae). It takes a lot of horn production to keep up with the downward migration of the epidermal laminae, which explains why the area of the terminal papillae also requires a rich blood supply.

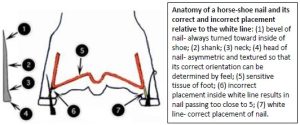

The anatomic term, white zone, is applied to the area on the bottom of the horse’s hoof where the wall meets the sole. This zone actually appears yellow or tan and can be appreciated best on a freshly trimmed hoof wall. Recall that the deeper part of the stratum medium and the stratum internum are non-pigmented, but the horn produced over the terminal papillae that fills in between the epidermal laminae is consistently pigmented. This alternating pattern of pigmented and non-pigmented horn results in the yellow/tan tissue. By anatomic definition, the white zone consists of the non-pigmented deeper part of the stratum medium (this layer is not always included in definition), the non-pigmented stratum intermum (epidermal laminae) and the pigmented horn produced by the terminal papillae lying between the epidermal laminae. The white zone extends from the sole border of the Pd to the ground surface. Farriers use the expression “white line”. When they trim and level the hoof wall for the shoe, the inner non-pigmented area of the stratum medium is obvious. They may use this “white line” as an additional guide for driving shoe nails into the hoof. If the nail is started inside the white line, it will likely pass too close to or even penetrate the sensitive tissue of the foot (referred to as “quicking” the horse).

- Sagittal section through foot of horse with magnified insets to illustrate details of distal hoof wall anatomy.

- Trimmed sole of equine foot showing white zone and white line features.

- Anatomy of a horse-shoe nail and its correct and incorrect placement relative to the white line.

- Horse hoof

- Horse hoof

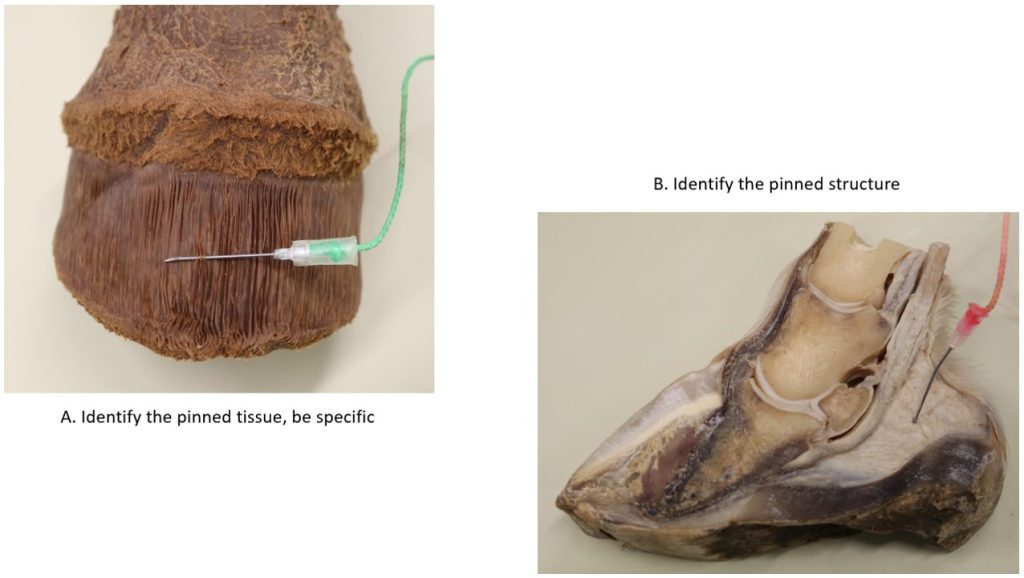

Holes and papillae: Note that wherever there are holes in the hoof capsule, there are corresponding papillae on the reciprocal dermal tissue. Papillae fit into holes. In those regions of the dermis where there are papillae (periople, coronary, frog, and sole), horn is not produced as a uniform, homogeneous substance. Rather, it is produced as tubules of horn, bonded together by intertubular horn. This configuration is known as tubular horn and it adds strength, resilience, and compressibility to the structure. The tubules essentially parallel the compressive forces (weight) on the structure. Like the flexor tendons, the hoof is not totally inelastic but is designed to “give” slightly under the compressive forces of weight-bearing (i.e., the hoof wall gives slightly and then rebounds after support). When you examine the outer surface of the hoof wall, you can appreciate this tubular structure. The horn resembles a bundle of hairs (tubules) stuck together with glue (intertubular horn). The tubules give the hoof its proximodistal, linear striations. In some hooves, lines of variable pigmentation accentuate the tubular pattern. Tubular horn is produced only where there are papillae; where there are laminae (stratum internum), only laminar horn is present.

Sagittal & Transverse Sections of Equine Digit

Observe: On the cut surface of a sagittal section, note the periople draping over the proximal border of the wall. Observe the narrow perioplic corium at the junction of hair and hoof. The coronary corium is much wider and conforms to the coronary groove of the hoof.

There is a rich venous plexus in the subcutis of this area, the coronary plexus, which extends around the coronary groove of the hoof.

- Sagittal section through digit of horse. 2

- Transverse section through distal right digit of horse, proximal view. 2

Observe: The inner, non-pigmented part of the stratum medium should be obvious and, just deep to it, the stratum internum, ie the epidermal laminae, that interdigitate with the dermal laminae. Note that the dorsal part of the parietal surface of Pd is parallel to the hoof wall. The periosteum of this part of the bone is modified to fuse with the laminar corium, which contains a rich plexus of veins, the dorsal plexus.

At the junction of wall and sole, the sole corium continues to the apex of the frog, where it is continued as the frog corium. Remember, corium is just another name for the dermis of the foot, and adjectives (e.g., perioplic, coronary, sole) are merely regional designations of this continuous layer of the integument. The corium of the frog is continued as the dermis of the skin between the bulbs of the heel.

Observe: Identify the wedge of tissue between the frog corium and the DDF tendon – it is the digital cushion.

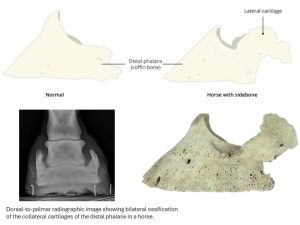

The digital cushion, a mass of fibrofatty connective tissue, represents a modification of the subcutis (i.e. the layer of skin deep to the dermis) and is important in the natural “pump action” of the equine foot, which functions to move blood out of the venous plexuses of the foot. The digital cushion, lying deep to the frog corium, saddles the spine of the frog. The latter acts not only as a stabilizer but also as a wedge to spread the compressed digital cushion abaxially. Between the sole corium and sole surface of Pd, and continuing between the frog corium and the digital cushion, is another rich venous plexus known as the palmar plexus. The palmar plexus extends proximoabaxially between the digital cushion and the cartilages of the hoof. The collateral cartilages of the foot are wing-like medial and lateral cartilage extensions attached by various ligaments to the bones of the digit. Ossification of the collateral cartilages of the foot can occur with age and imbalance in the foot – they are then referred to as “sidebones”, readily diagnosed on radiographs and sometimes by palpation.

Not only are the venous plexuses compressed during weight bearing, providing a sort of “fluid suspension,” but also the hoof itself is expanded at the heels by this force, which provides additional shock absorption. If you examine the upper surface of a used horseshoe immediately after its removal, you should observe that it has been polished at the heels by the alternate expansion and contraction of the hoof wall. This expansion is necessary for the normal function of the hoof and explains why the shoe is not normally nailed at the heels.

- (A) Lateral view of the bones and collateral cartilage of the equine foot. (B) Sagittal view of the soft tissues and synovial structures of the equine distal limb. 9

- Sagittal section through digit of horse. 2

- Sidebone in a horse (ossification of collateral cartilages).

- Horse pastern

- Horse distal limb

Foot of Ox

Observe: Examine specimens of the ox foot.

The hoof wall is divided into axial and abaxial parts that meet dorsally at the toe. The toe of each bovine hoof is directed somewhat axially (toward the interdigital space) as a result of the curvature of the abaxial part of the wall. In the newborn calf, an extension of soft, yellow horn is present on the sole surface of the hoof. This eponychium dries quickly and, as the calf walks, is usually worn away within a few hours.

The coronary groove is wider but shallower than that of the horse. The primary epidermal laminae are shorter than those of the horse. No secondary laminae are present in the ox, but the primary laminae are more numerous. The periople spreads out and merges with the horn of the bulb. The bulb of the hoof is large and, with the digital cushion, forms the digital pad, which corresponds to the bulbs and frog of the equine hoof. The bulb covers much of the supporting surface of the hoof and bears a larger share of the weight than the bulbs of the equine hoof. There are no bars or frog in the bovine hoof. The sole is a relatively small area surrounding the apex of the bulb and extending to the white zone.

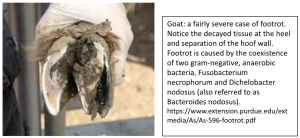

Clinical relevance:

Foot problems are one of the primary causes of lameness in cattle.

Foot of Pig and Small Ruminants

The hooves of the pig and small ruminants are similar and resemble those of the ox. Most foot problems in pigs involve the lateral digit and the lateral hoof is larger than the medial one. The bulb of the porcine hoof is large and bulges beyond the supporting surface. The sole of the pig hoof is relatively larger than that of small ruminants. In the small ruminant, the bulb covers almost the entire supporting surface. As in the ox, there are no secondary laminae in the pig and in the small ruminants. Similarly, the wall bears a much smaller percentage of the body weight than in the horse.

Review Videos

Horse foot – 22 minutes

Terms

| Foot anatomy – horse unless otherwise noted |

|

| Epidermal features | |

| Coronet/”coronary band” | junction of haired skin and hoof wall |

| Hoof capsule | the epidermal structure of the foot, consists of wall, sole, frog. |

| Toe, quarters, heels | Hoof wall subdivisions as viewed externally |

| Bars (of foot) | feature of hoof wall on ground surface |

| Sole (of foot) | |

| Frog: crura, apex, central groove, spine of frog | |

| Paracuneal/collateral grooves of frog | between bars and frog |

| Heel bulbs | |

| Perioplic groove | on inner surface of hoof wall, very narrow |

| Coronary groove | on inner surface of hoof wall, relatively wide |

| 3 layers of hoof wall = | |

| stratum externum | = periople |

| stratum medium | |

| stratum internum | = insensitive lamina or epidermal lamina |

| Tubular and intertubular horn | understand where it is found |

| ‘White line’ | unpigmented deepest part of stratum medium |

| Dermal features | |

| Perioplic corium | |

| Coronary corium | |

| Laminar corium and terminal papillae | |

| Sole corium | |

| Frog corium | |

| Additional features | |

| Digital cushion | modified hypodermis (subcutaneous tissue) |

| Collateral cartilages of foot | Horse |

| Vascular anatomy of foot | Horse |

| Coronary plexus | Concept only, not identified |

| Dorsal plexus | Concept only, not identified |

| Palmar plexus | Concept only, not identified |

| Foot anatomy – artiodactyls |

|

| hoof wall | |

| sole | |

| heel bulb | |

| digital pad | combination of heel bulb and underlying digital cushion |