Lab 3A: Nerves of the Abdominal Cavity

Learning Objectives

- Name and identify the nerves supplying the abdominal wall mm.

- Identify the autonomic nerves, ganglia, and plexuses of the abdominal cavity.

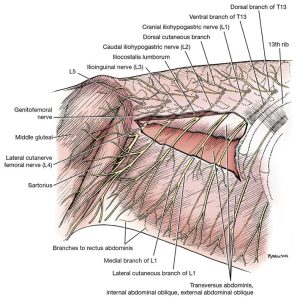

The cutaneous nerves of the abdomen differ somewhat from those of the thorax. The lateral cutaneous branches from the last five thoracic nerves do not follow the convexity of the costal arch but run in a caudoventral direction and supply the ventral and ventrolateral parts of the abdominal wall. The cutaneous branches of the first three lumbar nerves (L1-L3) perforate the lateral part of the abdominal wall and, as small nerves, run caudoventrally. They supply the skin of the caudolateral and caudoventral abdominal wall and the thigh in the region of the stifle.

Dissect: Do NOT dissect these cutaneous nerves.

Cranial to the cranioventral iliac spine, the lateral cutaneous femoral nerve (L4) and the deep circumflex iliac artery and vein (we’ll come back to these vessels in the next unit) perforate the internal abdominal oblique m. and appear superficially. The nerve arises from the fourth lumbar spinal nerve (L4) and is cutaneous to the cranial and lateral surfaces of the thigh.

Dissect: On the lateral surface of external abdominal oblique m., identity and isolate the cut stumps of the lateral cutaneous femoral nerve (L4) where they perforate the abdominal wall muscles just cranial to the cranioventral iliac spine. This nerve travels with the deep circumflex iliac artery and vein, so it may be easier initially to look for the latex from the vessels.

- Lateral view of the first four lumbar nerves.1

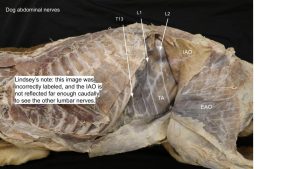

The ventral branches of the first four lumbar nerves form the cranial iliohypogastric, caudal iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, and lateral cutaneous femoral nerves, respectively. Do not be concerned with remembering these names. Rather, learn them as L1, L2, L3, and lateral cutaneous femoral nerves (for L4). The L1, L2, L3 ventral spinal nerves pass through the aponeurosis of origin of the transversus abdominis. Each has a medial branch that descends between the transversus abdominis and the internal abdominal oblique to the rectus abdominis. These medial branches supply these muscles and the underlying peritoneum. It is these medial branches that are identified running in parallel on the external surface of the transversus abdominis m. and they provide one way to recognize this muscle layer. It may be difficult to differentiate between the ventral branches of T13 and L1 without tracing them to the intervertebral foramina, which is not necessary. Usually the ventral branch of T13 courses along the caudal aspect of the thirteenth rib.

Observe: Review the previously separated muscle layers of the abdominal wall and confirm the parallel nerves coursing over the external surface of the transversus abdominis m.

- Lateral view of the first four lumbar nerves.1

The lateral branches of these ventral spinal nerves perforate the internal abdominal oblique and descend between the oblique muscles. They may be seen on the deep surface of the external abdominal oblique (there is no need to look). Each lateral branch supplies these muscles, perforates the external abdominal oblique, and terminates subcutaneously as the lateral cutaneous branch to the abdominal wall in that region. These cutaneous branches supply the skin of the caudolateral and caudoventral abdominal wall and the thigh in the region of the stifle. The craniolateral and cranioventral abdominal skin is supplied by the lateral cutaneous branches from the last five thoracic nerves.

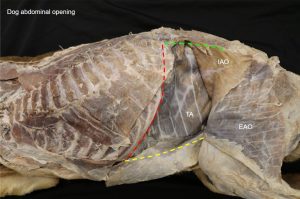

Nervous Structures of the Abdominal Cavity

Dissect: In a prior dissection, external abdominal oblique m. and internal abdominal oblique m. were reflected caudally. Depending on where these incisions were made, you made only need to cut through transversus abdominus m. to enter the abdomen, or make full thickness incisions (i.e., through all muscular layers). Make an incision just caudal to the costal arch, following its curve. Starting just caudal to the costal arch, make a full thickness longitudinal incision, parallel and ~1cm dorsal to the aponeurosis of insertion of the external abdominal oblique m. Extend the incision caudally past the umbilicus, stopping a few centimeters cranial to the inguinal canal anatomy. Dorsally, make an incision right under the epaxial muscles that extends to the pelvic limb.

Reflecting all of the muscular layers caudally, you are now observing the abdominal viscera. We will be discussing these organs in a later unit.

Dissect: Transect the dorsal half of the diaphragm from its attachment to the costal arch. This will allow for greater visibility into the dorsal wall of the abdominal cavity. Gently push the abdominal viscera to the right side of the abdominal cavity (as much as you can, try not to tear the organs) until you can see the dorsal body wall.

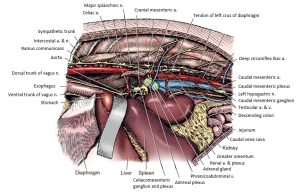

Recall that the vagal trunks pass through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm and course along the lesser curvature of the stomach. The dorsal vagal trunk gives off a celiac branch that passes caudodorsally and contributes to the formation of the celiac and cranial mesenteric plexuses. These abdominal aortic plexuses are nerve networks lying on and around (and indeed passing along) abdominal vessels for which they are named. Parasympathetic preganglionic axons in these plexuses follow the terminal branching of the respective blood vessels to the intestines at least as far caudally as the left colic flexure of the colon. The dorsal vagal trunk continues along the lesser curvature of the stomach to supply the visceral surface of the stomach, including the pylorus. All of these parasympathetic preganglionic axons will synapse with a second neuron within the wall of the organ where they terminate. They include the celiac, cranial mesenteric, caudal mesenteric, adrenal, and aorticorenal plexuses. The first three will be dissected.

In addition to the parasympathetic preganglionic axons described earlier, these plexuses contain sympathetic visceral efferent processes and numerous visceral afferent processes. Associated with many of these plexuses are abdominal sympathetic ganglia that contain cell bodies of sympathetic postganglionic axons. Within these ganglia are synapses with preganglionic sympathetic neurons that are destined to innervate the abdominal viscera.

Observe: Follow the sympathetic trunk from the thoracic cavity to the level of the kidney on the left side. It need not be dissected further caudally.

If your view of the sympathetic trunk is still obstructed by the ribs, you may cut the remaining costal arch at the dorsal aspect and reflect it ventrally.

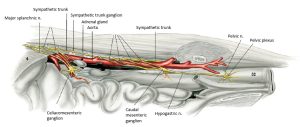

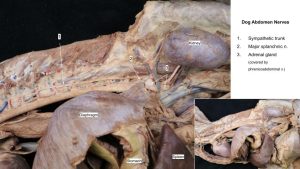

- Exposure of abdominal autonomic nervous system on left side. 1

- ANS of the abdomen and pelvis of the cat, left abdominal wall and os coxae removed and intestines retracted, lateral view. 4

Because most of the preganglionic axons in the sympathetic trunk at levels T10 to T13 pass into the major splanchnic nerve (see below) rather than into the lumbar region of the trunk, there is a distinct narrowing of the trunk caudal to the major splanchnic nerve. The trunk widens again as lumbar rami communicantes (communicating branches) and splanchnic components enter it.

The splanchnic nerves contain sympathetic axons that run between the sympathetic trunk and the abdominal autonomic ganglia as well as axons of visceral afferents coursing to the spinal cord.

The major splanchnic nerve leaves the sympathetic trunk at the level of the twelfth or thirteenth thoracic sympathetic ganglion. It passes dorsal to the crus of the diaphragm, enters the abdominal cavity, and courses to the adrenal and celiacomesenteric ganglia and plexuses (see next section).

Observe: Observe the origin of the major splanchnic nerve in the caudal thoracic cavity and trace it medio-caudally to the ganglia lying on the abdominal aorta.

- Exposure of abdominal autonomic nervous system on left side. 1

- ANS of the abdomen and pelvis of the cat, left abdominal wall and os coxae removed and intestines retracted, lateral view. 4

As noted previously, branches of the vagus and splanchnic sympathetic nerves intermingle around the major abdominal arteries to form nerve plexuses in the abdomen. The plexuses supply the musculature of the artery and arterioles, and the viscera supplied by the branches of that artery.

Several sympathetic ganglia are located in the abdomen in close association with the plexuses. These ganglia are collections of cell bodies of postganglionic axons. Preganglionic axons of sympathetic splanchnic nerves must synapse in one of these ganglia. Parasympathetic preganglionic axons (arising from the vagus nerve) do not synapse here but pass through the ganglia and plexuses to the wall of the organ innervated, where they synapse on a cell body of a postganglionic axon.

The celiac ganglia lie on the right and left surfaces of the celiac artery close to its origin – i.e. there are two celiac ganglia. They are often interconnected, and numerous nerves from the ganglia follow the terminal branches of the celiac artery as a plexus.

The cranial mesenteric ganglion is located caudal to the celiac ganglion on the sides and caudal surface of the cranial mesenteric artery, which it partly encircles. Most of its nerves continue distally on the cranial mesenteric artery as the cranial mesenteric plexus. Because of the close relationship of the celiac and cranial mesenteric plexuses and ganglia, they are referred to as the celiacomesenteric ganglion and plexus.

Dissect: Bluntly dissect the celiacomesenteric ganglion and plexus.

- Exposure of abdominal autonomic nervous system on left side. 1

- ANS of the abdomen and pelvis of the cat, left abdominal wall and os coxae removed and intestines retracted, lateral view. 4

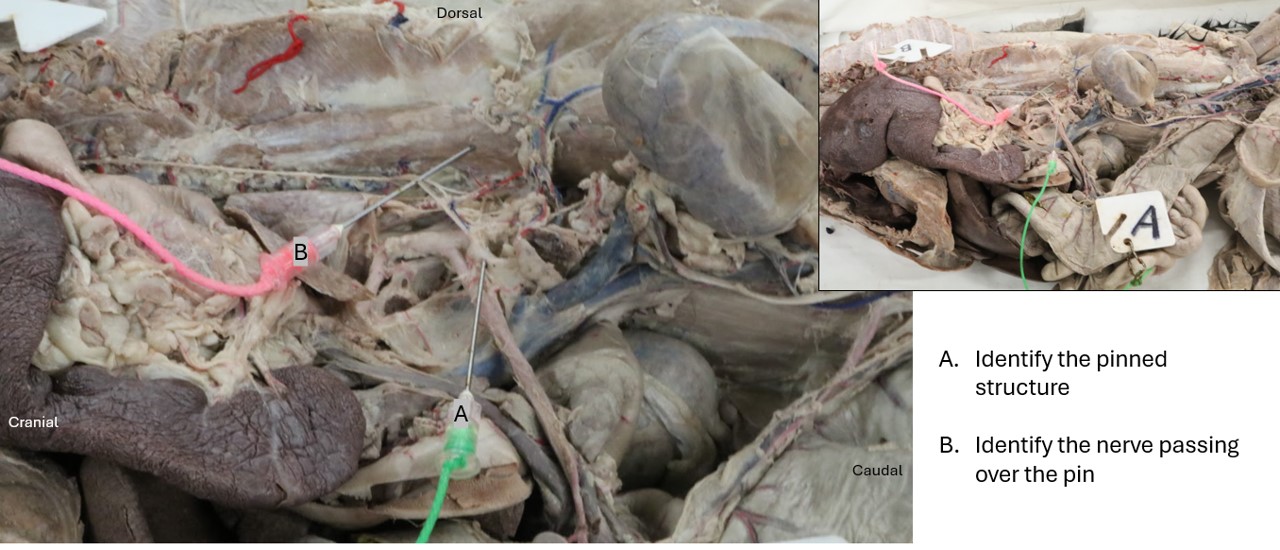

The caudal mesenteric ganglion and plexus is located ventral to the aorta around the caudal mesenteric artery, which is an unpaired branch of the aorta caudal to the kidneys that supplies a portion of the colon and rectum. Lumbar splanchnic nerves enter the ganglion on each side. Branches may also come from the aortic and celiacomesenteric plexuses. Some of the nerves leaving the ganglion continue along the artery as the caudal mesenteric plexus.

The right and left hypogastric nerves leave the caudal mesenteric ganglion and course caudally near the ureters. They run in the mesocolon, incline laterally, and enter the pelvic canal. Their connections with the pelvic plexuses will be described later. These nerves carry sympathetic fibers.

Dissect: Locate and bluntly dissect the caudal mesenteric ganglion and plexus and the left and right hypogastric nerves, both of which extend caudally from the caudal mesenteric ganglion and plexus. The hypogastric nerves are relatively small and easy to break, so take your time and carefully dissect them with a blunt probe. These structures are located very caudally within the abdomen, near the pelvic cavity.

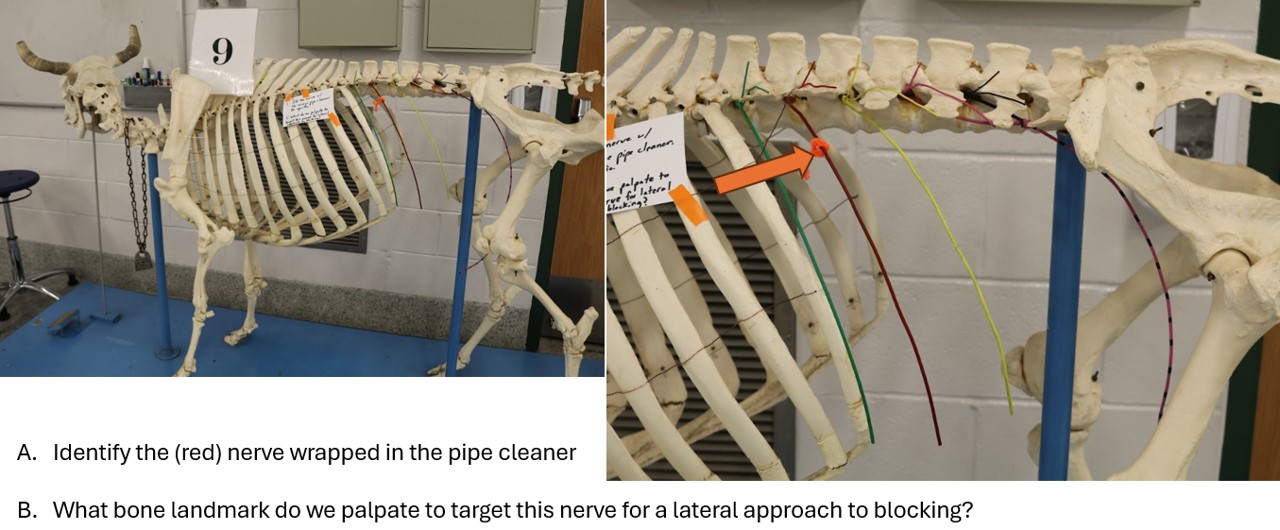

The Ungulate Perspective

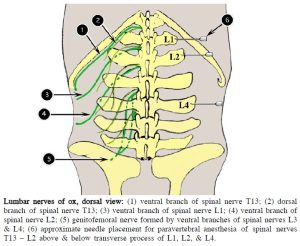

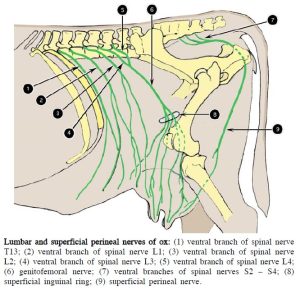

Regional anesthesia of the flank is important in ruminants to perform surgical procedures such as rumenotomy and cesarean section via laparotomy (flank incision). Of principal concern in anesthesia of the flank are the dorsal and ventral branches of spinal nerves T13, L1, and L2. It is important to understand the distribution of these nerves in the ruminant.

*We will not be opening the abdominal walls of the ungulates for this unit, so focus your attention of the identification of abdominal nervous structures in the carnivores.*

Observe: View the wires on the ox skeleton to visualize the spinal nerve branches of the ruminant. Pay particular attention to where we might perform nerve blocks of the spinal nerves T13, L1, and L2.

Clinical relevance:

Paravertebral anesthesia of spinal nerves T13, L1 and L2 is performed to facilitate laparotomy in ruminants.

Cow paravertebral nerve block – 1 min

- Lumbar nerves of ox, dorsal view. 2

- Lumbar and superficial perineal nerves of ox.2

We will not bother observing the autonomic nervous structures in the abdomens of the ungulates, as their anatomy is more or less equivalent (see image below: evolutionary conservation in action yet again!). As you move forward in the veterinary curriculum, be aware that large animals have the same large autonomic nervous structures that we observe in the carnivores.

- Schematic illustration of the sympathetic nerves and ganglia of the horse. 7

Review videos

Dog abdominal nerves – 3 min, watch until 4 min

Cat thorax and abdomen nerves – watch until 17 min

Dog abdominal nerves – watch until 7 min

Terms

| Nervous Structure | Species |

| External abdominal oblique m. | Carnivore |

| Internal abdominal oblique m. | Carnivore |

| Transversus abdominus m. | Carnivore |

| Nerves of the abdominal wall | See below |

| Cutaneous brr. of T13-L3 | All |

| Lateral cutaneous femoral n. | All |

| Dorsal vagal trunk | Carnivore; understand that it passes through the esophageal hiatus, don’t identify in abdomen |

| Ventral vagal trunk | Carnivore; understand that it passes through the esophageal hiatus, don’t identify in abdomen |

| Lumbar sympathetic trunk | Carnivore |

| Major splanchnic n. | Carnivore |

| Celiacomesenteric ganglion and plexus | Carnivore |

| Caudal mesenteric ganglion and plexus | Carnivore |

| Left and right hypogastric nn. | Carnivore |