Lab 4: Neck Vasculature

Learning Outcomes

- Identify the carotid sheath and list the structures within it.

- Identify the common carotid artery, internal jugular vein, tracheal trunk, and the external jugular vein.

- Describe external jugular venipuncture in the carnivore and ungulate species.

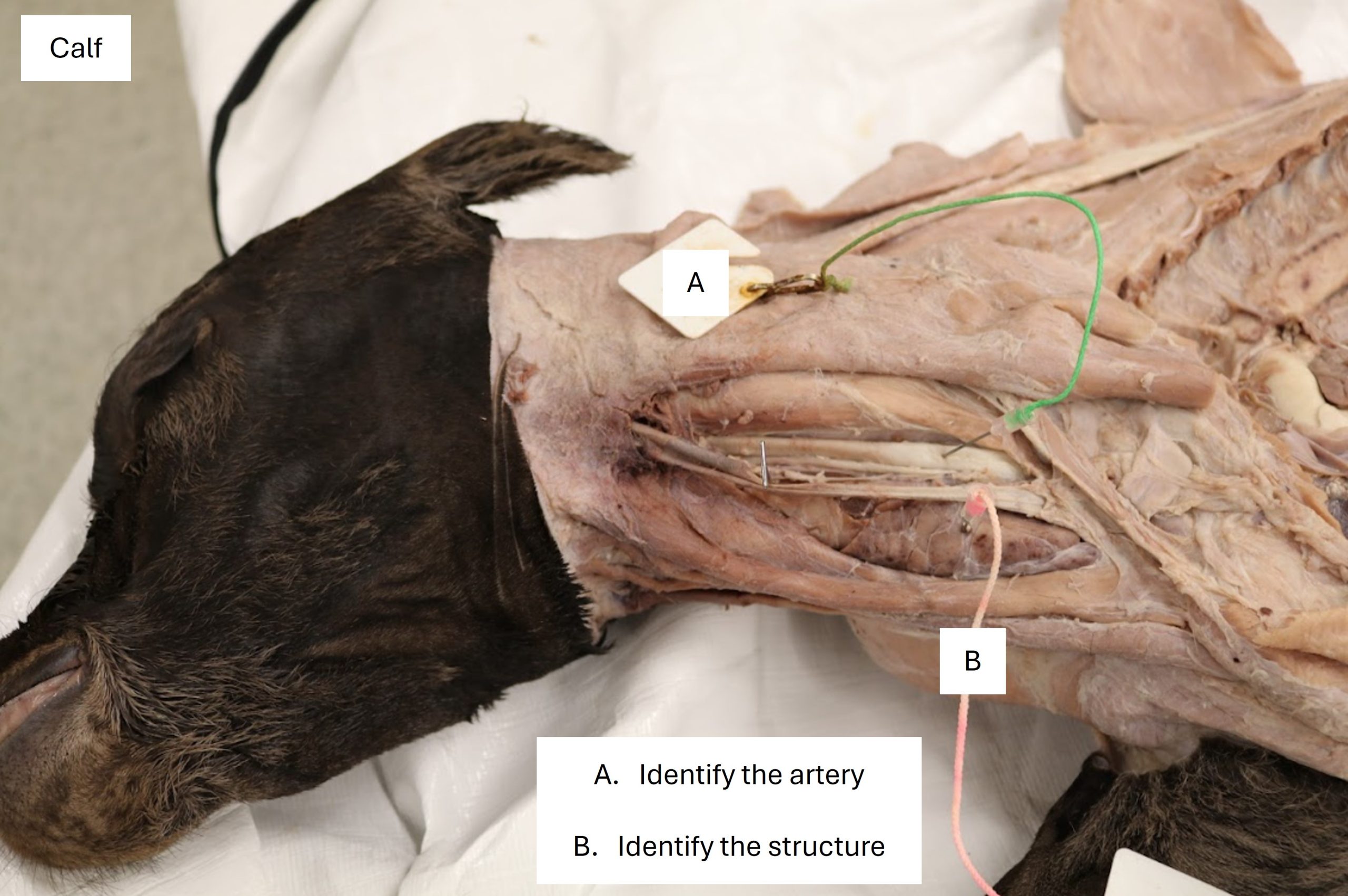

- Identify the cervical thymus in the calf.

Carnivore Neck Vasculature

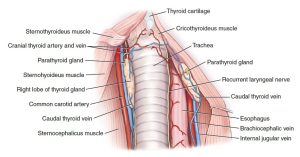

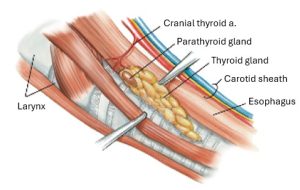

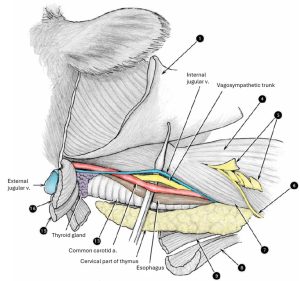

Recall that the deep fascia of the neck is a strong wrapping that extends under the sternocephalicus, omotransversarius, and the cleidocephalicus (remember this muscle is a segment of the brachiocephalicus m.). The fascia covers the sternohyoideus and sternothyroideus ventrally and surrounds the trachea, thyroid gland, larynx, and esophagus. The deep fascia that covers the common carotid artery, vagosympathetic trunk, internal jugular vein, and tracheal trunk is the carotid sheath.

Observe: On the same side of the body as the opened thorax, observe the fused sternohyoideus and sternothyroideus 2 cm from their origin and lift them to their insertions. Deep to these muscles, identify the trachea, esophagus, and carotid sheath and its contents. On the left side, the left common carotid artery, vagosympathetic nerve trunk, internal jugular vein, and tracheal trunk (duct) run in the angle between the esophagus and the longus capitis muscle. The corresponding structures on the right side are located lateral to the trachea.

Note that the larynx and thyroid glands, which will be observed during the head section for the carnivore, are also located in the neck but are located too cranially for us to identify at this time.

Recall that the tracheal trunk and internal jugular v. can often be difficult to visualize. See if you can find them, but do not spend too much searching. Be able to list all of the structures within the carotid sheath. (The tracheal trunks may be found in each carotid sheath or parallel to the sheath and its contents. For our purposes, we will list them as being located within the carotid sheaths.)

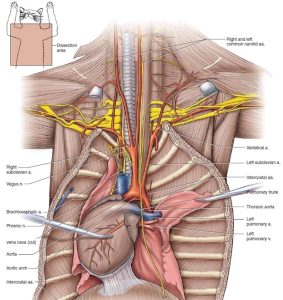

- Arterial, partial venous system and nerves anterior to the heart of the cat in ventral view. 5

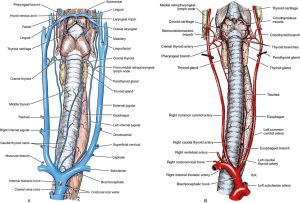

- Veins (A) and arteries (B) of the neck of the dog, ventral view. 1

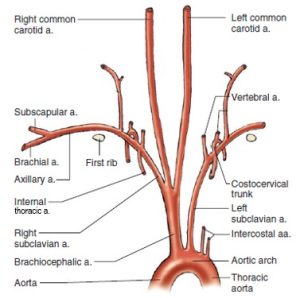

- Schematic illustration of the arteries cranial to the heart of the cat, ventral view. 5

- Neck of the dog, ventral view. 9

- Thyroid gland of the cat, lateral view. 4

- Carotid sheath

- Common carotid a.

- Vagosympathetic trunk

- Internal jugular

- Tracheal trunk

- Dog external jugular vein

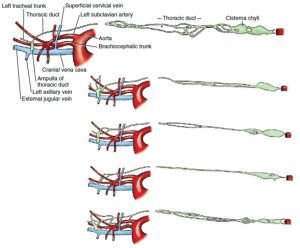

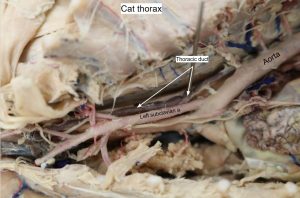

The thoracic duct is the chief channel for the return of lymph from lymphatic capillaries and ducts to the venous system and was identified in the thoracic vasculature lab. It begins in the sublumbar region between the crura of the diaphragm as a cranial continuation of the cisterna chyli. The latter is a dilated structure that receives the lymph drainage from abdominal and pelvic viscera and the pelvic limbs. The thoracic duct runs cranially on the right dorsal border of the thoracic descending aorta and the ventral border of the azygos vein to the level of the sixth thoracic vertebra (it may not be visible along this path). Here it crosses the ventral surface of the fifth thoracic vertebra and courses on the left side of the middle mediastinal pleura. It continues cranioventrally through the cranial mediastinum associated with the surface of the esophagus in this area, to reach the left brachiocephalic vein, where it usually terminates. The thoracic duct also receives the lymph drainage from the left thoracic limb and the left tracheal trunk (from the left side of the head and neck). The lymph drainage from the right thoracic limb and the right tracheal trunk (from the right side of the head and neck) form a right lymphatic duct that enters the venous system in the vicinity of the right brachiocephalic vein. There are often multiple terminations of a complicated nature, which may include swellings or anastomoses. Lymphatic channels are difficult to see unless they are congested with lymph or refluxed blood. They are frequently double.

Define the tracheal trunks and identify them in the carotid sheath, if possible. Describe the structures which are drained by the left and right tracheal trunks.

- variations of the thoracic duct of the dog and its entrance into the cranial vena cava. 1

- Dog left lateral thorax

- Cat thoracic duct

Observe: Identify the external jugular vein on the side of the neck.

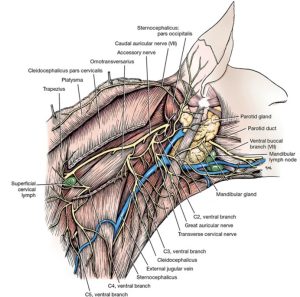

The external jugular vein is formed by the linguofacial and maxillary veins, which will be reviewed in the head lab. The ovoid body that lies in the fork formed by these veins is the mandibular salivary gland, which will be studied during the alimentary system unit. The mandibular lymph nodes lie on both sides of the linguofacial vein, ventral to the mandibular salivary gland and will also be studied in the head section of this unit. The mandibular lymph nodes and linguofacial and maxillary veins are all FYI until the head dissection but may be used now to help identify the external jugular vein at this time.

- Veins of the head and neck of the dog. 1

- Dog external jugular vein

Clinical Application: External Jugular Venipuncture in the Carnivore

The external jugular vein is a common location for venipuncture in the dog and cat. Watch the two Panopto videos at the below links, and be able to answer questions about them.

Feline External Jugular Venipuncture

Canine External Jugular Venipuncture

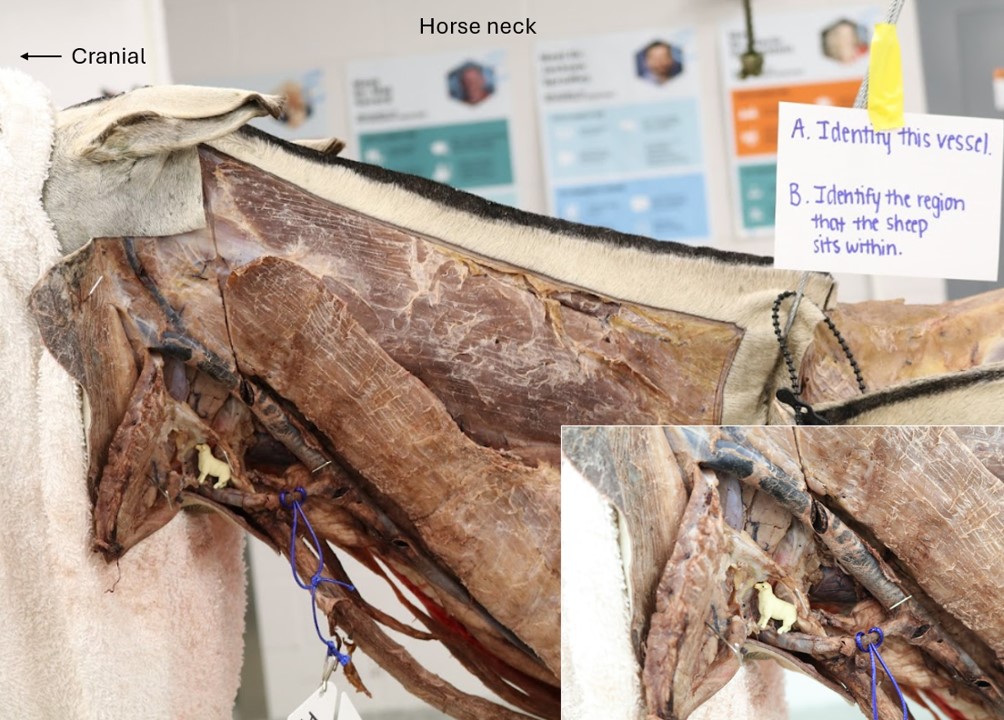

Review (no dissection necessary): The External Jugular Vein and Jugular Groove in the Ungulates

Equine and Ruminant

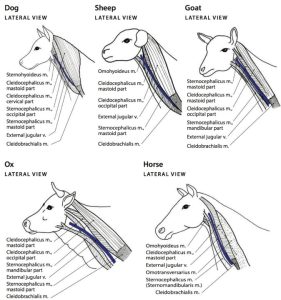

Review the brachiocephalicus m. subparts, which include the cleidobrachialis and the cleidocephalicus (mastoid part). FYI: Ruminants also have an occipital part to their cleidocephalicus m.

The sternocephalicus m. is one muscle in the horse. (FYI: often called the sternomandibularis) and two parts in the ox and goat (FYI: sternomandibularis and sternomastoideus). FYI: In the goat ‘sternozygomaticus’ is often used in place of sternomandibularis because the muscle inserts on the zygomatic arch in this species.

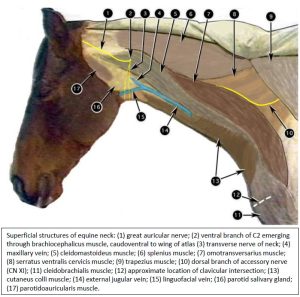

Observe: Review the superficial muscles of the ventral and lateral neck, and the cranial shoulder region, i.e. the omotransversarius m., brachiocephalicus m., sternocephalicus m. (aka, sternomandibularis in horse). Again note-the ventral border of the omotransversarius m. is fused to the brachicephalicus m. in the horse.

In the ungulates, the brachiocephalicus and sternocephalicus mm. form the dorsal and ventral boundaries of the jugular groove respectively. This groove accommodates the external jugular vein which is commonly used for venipuncture in the horse and ruminants.

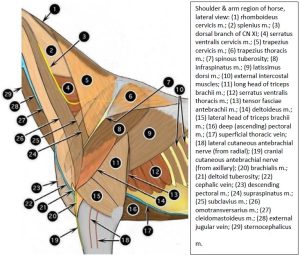

- Shoulder & arm region of horse, lateral view. 2

- Superficial structure of equine neck. 2

- Deeper structures of equine neck. 2

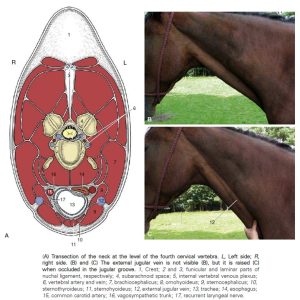

- Transection of the neck at the level of the fourth cervical vertebra. 8

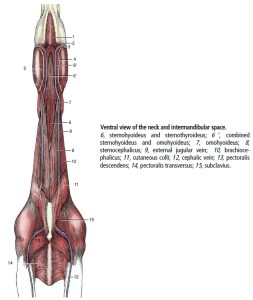

- Ventral view of the neck and intermandibular space of the horse. 8

- Comparative diagrams of the different major subdivisions of the brachiocephalicus and sternocephalicus muscles in common domestic animals, lateral views. 5

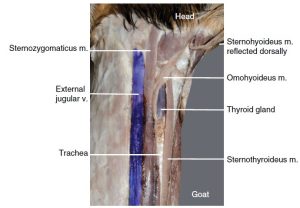

- Ventral neck of the goat. 12

- Calf external jugular v.

- Calf strap muscles

- Goat strap muscles

Review: There is also a medial boundary (‘backstop’) of the jugular groove in the cranial half of the neck.

Recall that in the horse, this backstop or medial boundary is the omohyoideus m. In the ruminant, the medial boundary is formed by the sternomastoideus (FYI), again, a part of the sternocephalicus.

Identify the external jugular v. List the muscles which form the dorsal, ventral, and medial boundaries of the jugular groove in the ruminant and equine.

FYI – the omohyoideus m. is also readily seen in the goat and is identifiable in the ox. In sheep, there is only one part to the sternocephalicus m., the mastoid part. Without a mandibular part of the sternocephalicus the ventral border of the jugular groove in sheep is less well defined and represented only by the mastoid part, which also forms the medial border cranially.

Clinical Application: External Jugular Venipuncture in the Ruminant and Equine

Review again:

The brachiocephalicus and sternocephalicus mm. form the dorsal and ventral boundaries of the jugular groove respectively, in both equines and ruminants. This groove accommodates the external jugular vein which is commonly used for venipuncture in these species.

There is also a medial boundary (‘backstop’) of the jugular groove in the cranial half of the neck. The omohyoideus m. forms this medial boundary in the equine, and in the ruminant, the medial boundary is formed by the sternocephalicus.

Review the lecture slides below and watch the linked Panopto video below, and be able to answer questions about the slides and video:

Equine External Jugular Venipuncture

Drugs given IA instead of IV can cause seizures. In this case, the owner accidentally gave Banamine (an NSAID frequently used for colicing horses) IA, but the horse managed to remain standing while having seizures. You can imagine how dangerous it would be for both the horse and human to have a horse fall during a tonic clonic (“grand mal”) seizure.

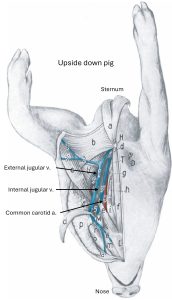

External Jugular Vein in the Pig

Observe: Observe the external jugular vein of the pig.

Clinical Application: External Jugular Venipuncture in the Pig

Note that the external jugular vein is not readily accessible for venipuncture in the same location as the horse and ruminant because there is no definable jugular groove and the vein is never in a subcutaneous position. Instead, the needle is inserted in the jugular fossa, on a line from the manubrium of the sternum to the base of the right ear. A right-sided approach is recommended as the phrenic n. lies near the external jugular v. on the left and is more vulnerable to injury.

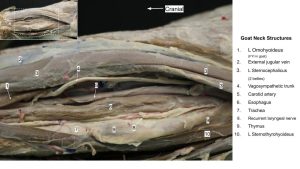

Structures of Carotid Sheath (Ungulates)

Observe: Reflect the sternocephalicus muscle(s) and omohyoideus m. as needed in the cranial third of the neck to further expose the trachea, esophagus and carotid sheath structures. Reflect the carotid sheath (i.e. the fascia surrounding the following structures) and identify the common carotid artery, vagosympathetic trunk, and when present, the internal jugular vein . The internal jugular vein is not typically present in the horse or small ruminants, but it is present in the pig, where it a relatively large structure compared to that in the carnivore. If possible, observe the tracheal trunk. Be able to list the structures within the carotid sheath in each species.

- Carotid sheath of the calf. 2

- External and internal jugular veins of the pig. 28

- Calf neck structures

- Goat Neck Structures

- Goat Neck Structures

Clinical Application: Injury to Structures of the Carotid Sheath

These structures are vulnerable to injury (trauma, irritation from injections made perivascular to the external jugular v.); the recurrent laryngeal n. develops a neuropathy that results in laryngeal hemiplegia in the horse (discussed in respiratory unit); inadvertent intracarotid injection is possible when attempting IV external jugular injections.

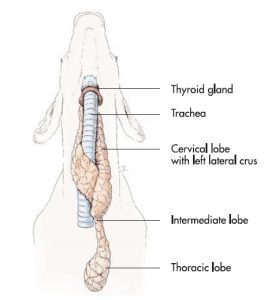

Thymus – cervical portion

The cervical part of the thymus typically atrophies within the first few months of life in the horse, and therefore, is not usually found except in the young foal. In contrast, the ruminant thymus is identifiable, even in the adult, as a pale, lobulated structure. The right and left cervical lobes are especially well developed in the calf and can extend along the length of the cervical trachea. The thymus of the pig is very well developed at the usual slaughter age of about 6 months. The thymus has a vital role in developing cell-mediated immunity through its production of T-cells.

Observe: Identify the cervical part of the thymus in the calf and pig. Portions of thymus may be viewed in the goat, too.

Clinical Application: Sweet Bread

The thymus of calves is saved at slaughter as the so-called “sweetbread”.

- Carotid sheath of the calf. 2

- Thymus of the calf. 7

- Calf neck structures

- Goat Neck Structures

This concludes the content for the neck cardiovasculature lab. Please continue on and begin the Thoracic Limb Vasculature lab today. You will need this time to complete the thoracic limb lab.

Review videos

Dog carotid sheath – 2 min

Dog carotid sheath, watch until 14:30 – 2 min

Horse jugular groove and Viborg’s triangle, watch until 4:30 – 2 min

Horse carotid sheath, watch until 10:00 – 1 min

Goat jugular groove and carotid sheath, watch until 7:45 – 4 min

Calf jugular groove and carotid sheath – 4 min

Pig carotid sheath – 3 min

Terms

| Neck |

|

| Features | Species |

| External jugular v | All |

| Jugular groove | Do not identify, but know the boundaries of the groove. |

| Brachiocephalicus m. – dorsal boundary of jugular groove | Ungulates |

| Sternocephalicus m. – ventral boundary of jugular groove | Ungulates |

| Omohyoideus m. – medial boundary of jugular groove

Sternocephalicus m. – medial boundary of jugular groove |

Equine

Ruminants |

| Carotid sheath | All |

| Common carotid a | All |

| Vagosympathetic trunk | Know it is included in carotid sheath |

| Internal jugular v. | Carnivore and pig |

| Tracheal trunk | All (know location and what they drain) |

| Thymus | Calf and pig |