Lab 7A: Lower Respiratory Tract 2 – Lungs, trachea, bronchi

Learning Objectives

- Describe and identify the lungs of carnivores and ungulates, comparing and contrasting features.

- Describe and identify the trachea and bronchi of carnivores and ungulates, comparing and contrasting features.

- Associate normal anatomy with clinical diseases and procedures.

Lab Instructions:

The limited dissection required is performed by teams on carnivore cadavers. Otherwise much of the content is also learned on available lab prosections and models, wet and dry. Once the carnivore material has been considered, move to the ungulate specimens to learn comparative features and to complete the learning goals.

Lungs

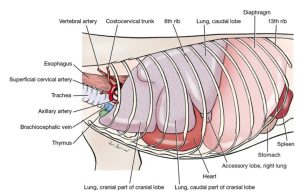

Observe: At this time, the carnivore cadaver has one lung removed (performed during the Cardiovascular unit) and one lung remains in situ. Study both lungs to identify structures as described and bolded.

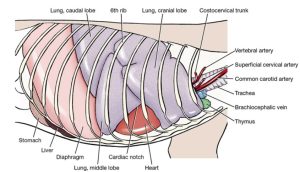

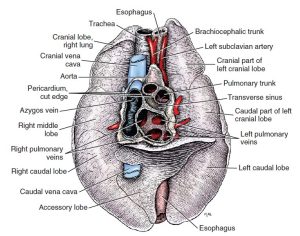

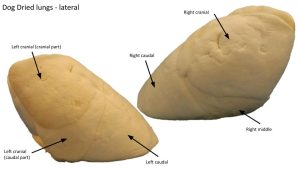

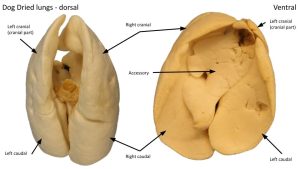

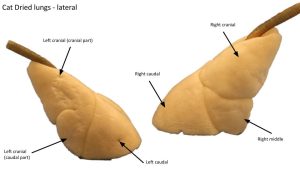

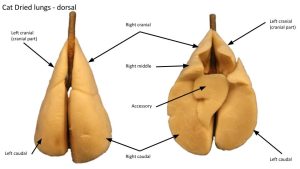

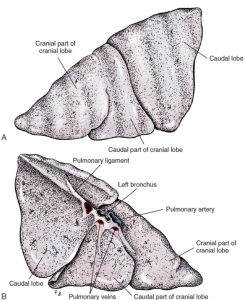

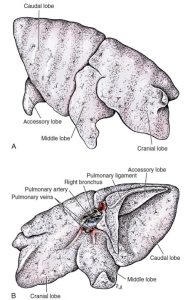

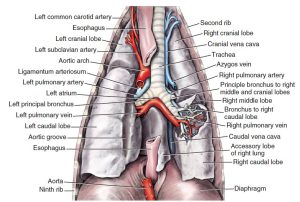

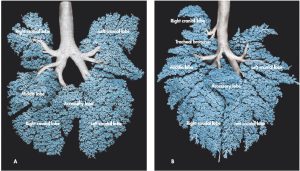

The right and left lungs are semi-pyramidal shaped organs possessing a rounded cranial end, called the apex, and a slightly concave, and much broader, caudal end, called the base. Each lung is divided into lobes based on the branching pattern of its principal bronchus into lobar bronchi (bronchi will be described in a later section). The left lung is divided into cranial and caudal lobes by deep fissures. The left cranial lobe is further divided into cranial and caudal parts. The right lung is divided into cranial, middle, caudal, and accessory lobes. The accessory lobe is tucked ventromedially into a deep space called the mediastinal recess, bounded by the plica vena cava and caudal vena cava laterally, and the mediastinum medially. Therefore, the accessory lobe can be viewed from the left pleural cavity by looking through the relatively thin, translucent caudal mediastinum.

Observe: If the cadaver has the right lung still in situ it can be difficult to identify the accessory lung lobe, hidden away in the mediastinal recess, and the embalmed lung is less flexible to move lobes around. Give it a go by carefully retracting the right caudal lung lobe. And, see if you can view the accessory lobe through the caudal mediastinum from the left side, or check out a removed right lung.

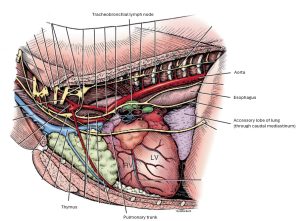

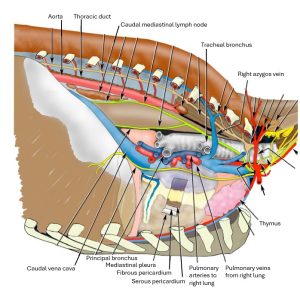

- Thoracic viscera, left lateral view. 1

- Thoracic viscera within the rib cage, right lateral view. 1

- Dorsal wall of the pericardial sac, with adjacent structures, ventral aspect. 1

- Right lung lobes

- Left lung lobes

- Left and right dog lungs

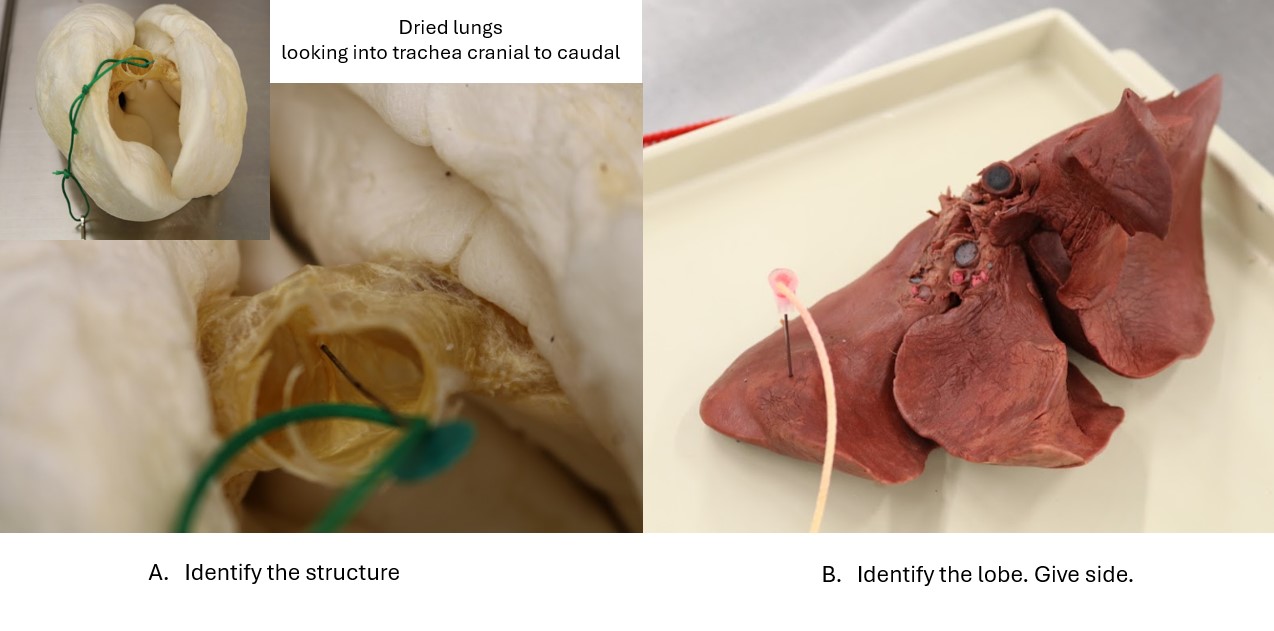

- Dried dog lungs

- Dried dog lungs

- Dried cat lungs

- Dried cat lungs

Clinical application: lung auscultation

With an understanding of the lung lobe distribution and location, auscultation of the lung sounds can be carefully refined to include what lobe or region may be involved in pathology. On each side, multiple (some suggest 4-6) sites over the area of the pleural cavities should be listened to.

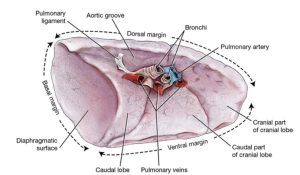

Each lung has a root and a hilus. The root of the lung (radix pulmonis) refers to the structures that enter and leave the lung, i.e. vessels, bronchi, lymphatics. Recall, these structures are covered by pleura as it continues from the mediastinal (parietal) pleura onto the lung surface to become pulmonary (visceral) pleura. The root of the lung attaches the lung to the mediastinum. The hilus of the lung (hilux pulmonis) is the area on the lung where the structures of the root enter and leave.

- Left lung of the dog, medial view. 1

- Left lung. A, Lateral aspect. B, Medial aspect. 1

- Right lung. A, Lateral aspect. B, Medial aspect. 1

Observe: On the removed lung the root and hilus are readily viewed. In latexed cadavers, red and blue sectioned vessels typically represent pulmonary veins and arteries, respectively. This seems counterintuitive but makes sense by mapping the flow of latex, when red latex is injected into the common carotid a. and blue latex is injected into the external jugular vein. Can you track the latex path to the pulmonary vessels? There is usually a pulmonary vein exiting each lung lobe and draining directly to the left atrium of the heart (considered in the CVS unit).

Observe: On the attached lung, it is possible to pass fingers around the root of the lung but it is a tight space. Recall and view the presence of the pulmonary ligament related to the caudal lung lobe.

The cardiac notch (already studied in the Cardiovascular System) is a lung border feature (i.e. it is not a heart feature, despite its name), and it is prominent on the right lung in carnivores. It is identified as the wide, ‘triangular indentation’ in the lung border as it passes from the cranial to the middle lung lobes. The apex of the notch is continued by the interlobar fissure between the cranial and middle lobes. Because of the cardiac notch (and hence it being so named), a large area of the right aspect of the heart wall (the region of the right ventricle) is visible, and in direct proximity to the thoracic wall (see clinical relevance box).

- Thoracic viscera within the rib cage, right lateral view. 1

Observe: On an in situ or removed right lung, trace the ventral border of the cranial lung lobe in a caudal direction, starting at the lung apex. When the border makes a sudden turn dorsally, you are now on the border of the cardiac notch feature. At the ‘top’ of the notch, note the interlobar fissure continuing between the cranial and middle lung lobes. Then head back ‘down’ ventrally to complete the contour of the cardiac notch where the middle lobe ventral border makes a sharp turn at is ventral tip (to then continue as the basal border of the lung).

Clinical relevance – cardiac notch

As also considered in the CVS: The cardiac notch offers a convenient window to the heart, from an external approach, without lung tissue intervening. The right ventricle of the heart is accessible for cardiac puncture (cardiocentesis) at this location. The cardiac notch is aligned mostly with the 4th and 5th intercostal spaces and external palpation of these spaces provides a landmark for determining where to insert a device. Ultrasonography is entirely helpful too! The cardiac notch is also a good ‘lungmark’ to know cranial from middle lung lobes on the right.

All right, a decision has been made…..do not remove the remaining attached lung. Leave it in situ and continue on, considering the following applied anatomy on the side with the lung still attached.

Trachea and bronchi (singular, bronchus)

Observe: Read the descriptions and then identify the following bolded features, using the cadaver and models. Latexed models of the trachea and bronchial tree are particularly useful to recognize the pattern of airways.

Tracheal anatomy was also considered in Lab 2A.

The trachea (the ‘windpipe’) consists of a series of connected tracheal cartilages – C-shaped cartilaginous structures, positioned with their opening dorsally. This dorsal space is filled with transversely aligned tracheal muscle, joining the two ends of the cartilage. In carnivores the tracheal muscle is on the outside of the cartilages, in other species it is located on the inside of the cartilages. Annular ligaments bind one tracheal cartilage to the next, and a mucous membrane and submucosa line the lumen. The trachea is subdivided into a cervical part and a thoracic part.

Observe: On the cadaver, identify again, the trachea and its tracheal cartilages, in the neck and thorax.

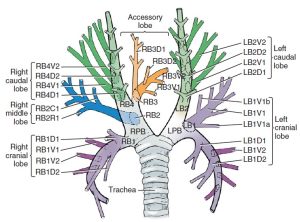

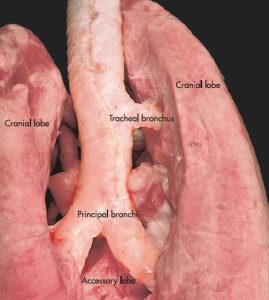

At the tracheal bifurcation the left and right principal bronchus (bronchus principalis) arise. The carina is the luminal vertical partition or crest, between the principle bronchi at their origin from the trachea. The carina is viewed during bronchoscopy. Each principal bronchus divides into lobar bronchi (bronchi lobares), providing the conduit for air to enter and leave individual lung lobes. There is one lobar bronchus per lobe of lung, therefore in the carnivore, there are four lobar bronchi on the right, and two on the left. On the left the cranial lobar bronchus quickly divides into cranial and caudal parts to supply the same named parts of that lung lobe. Cartilaginous bronchial rings extend into the lobar bronchi. Within each lung lobe, segmental bronchi (bronchi segmentales) branch off the lobar bronchus dorsally and ventrally except for the right middle lobe, where they are positioned cranial and caudal.

- Schematic bronchial tree of the dog in dorsal view. 1

- Bronchial tree and associated structures, dorsal aspect. 1

- Carina and right and left principal bronchi (RPB, LPB) of the cat. R. Caccamo

Observe: At the sectioned root of the removed lung, lobar bronchi are likely present (versus a single principle bronchus) and can be distinguished from vessels by the presence of cartilage in their walls (and ideally the lack of latex in their lumens).

Recall from the Cardiovascular System, that the pulmonary trunk supplies each lung with a pulmonary artery. At the root of the lung, the left pulmonary artery usually lies cranial to the left principal bronchus. The right pulmonary artery is ventral to the right principal bronchus. The artery and bronchus are at a more dorsal level than the veins (recall this detail when considering radiographs of the thorax – ‘veins are ventral and central’ is a catchy way to remember pulmonary veins are ventral to the bronchus and pulmonary artery on lateral radiographs and medial to those same structures on dorsoventral and ventrodorsal radiographs).

Observe: Once again, take a second to identify the tracheobronchial lymph nodes located at the bifurcation of the trachea and also farther out on the bronchi. These can be especially challenging to find in the feline.

- Dissection of the thoracic region, right side. 1

- Tracheobronchial lymph node

Comparative ungulate anatomy

Observe: Move on to the prosected ungulate cadavers and the various wet and dry models in the lab to study the comparative ungulate anatomy. For the ungulates, lungs have been removed from both sides and should be available, along with other lung specimens. Read the descriptions below and Identify structures as listed in the terms table.

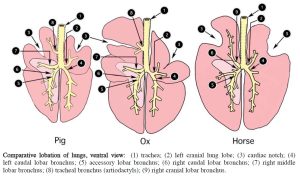

We know now that the typical lung lobation pattern is 2 lobes on the left and 4 on the right. And important to remember, lung lobation is based on the branching pattern of the bronchial tree, and not on the presence or absence of obvious fissures between regions of the lung.

As for carnivores, the C-shaped tracheal cartilages are positioned with their opening dorsally. Distinct from carnivores, the trachealis m. is attached on the inside/deep surface of the tracheal cartilages in ungulates. Annular ligaments bind one tracheal cartilage to the next, and a mucous membrane and submucosa line the lumen. The trachea is subdivided into a cervical part and a thoracic part. The cross-sectional shape of the trachea varies between species.

Horse notes

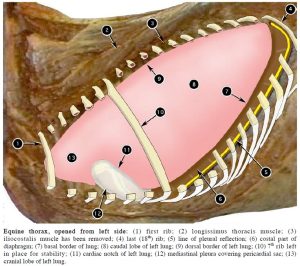

With the exception of the accessory lobe, the lungs of the horse are not divided into distinct lobes by deep fissures and the horse has no right middle lung lobe. The cardiac notch is present, left and right, and partially separates each equine lung into relatively small cranial and very large caudal lobes.

The horse trachea is flattened dorsoventrally and consists of 48-60 cartilages. The tracheal bifurcation is clearly visible on endoscopic examination at the site of the carina.

- Equine thorax, opened from left side. 2

- Comparative lobation of lungs, ventral view. 2

- Horse lungs

Artiodactyl notes

The lungs of ruminants and the pig do have distinct lobes and, in ruminants, both cranial lobes are subdivided into cranial and caudal parts, whereas in the pig, only the left cranial lobe is so divided (similar to the dog and cat) A cardiac notch is present on the left and right sides. Intralobar lobulation of the lung is clearly evident in the ox, less conspicuous in the goat and the pig, and hardly detectable in the sheep.

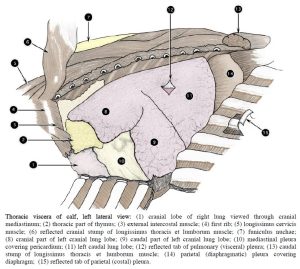

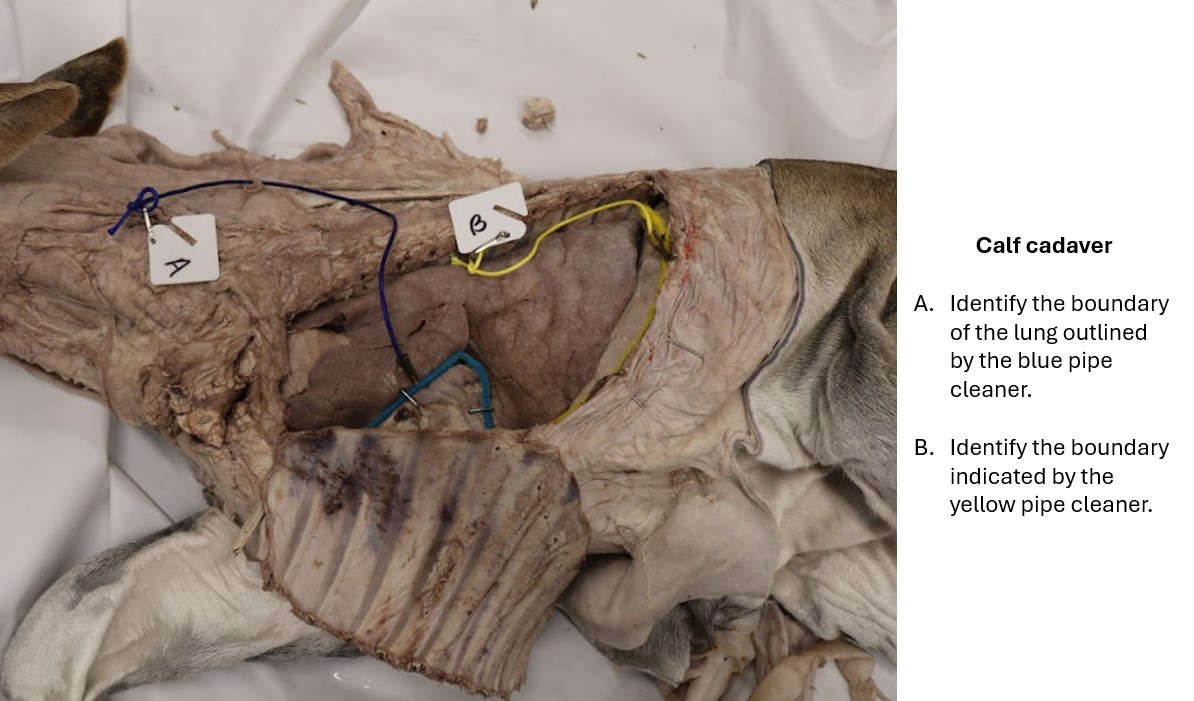

- Thoracic viscera of calf, left lateral view. 2

- Respiratory structures of the ox thorax. 2

- Comparative lobation of lungs, ventral view. 2

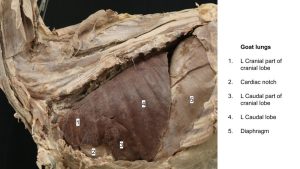

- Goat lungs

- Pig lungs

- Tracheal bronchus

The artiodactyl trachea has a distinct feature not seen in the carnivore or horse. The right cranial lung lobe receives a dedicated tracheal bronchus (bronchus trachealis). This bronchus exits the trachea a notable distance cranial to the tracheal bifurcation into the standard left and right principal bronchus. Awareness of the tracheal bronchus in our ruminant and pig patients is highly relevant, for example, when endotracheal intubation is performed.

- Trachea and bronchial tree corrosion cast of a dog (A) and a pig (B). 9

- Lungs of a pig, demonstrating the tracheal bronchus (dorsal aspect). 9

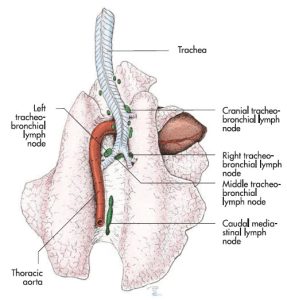

- Tracheobronchial lymph nodes of the lung of the ox. 9

The ruminant trachea consists of 48-60 cartilages. It is relatively oval in cross section on the live ox, whereas in the goat it is more U-shaped on cross section. The sheep has 3 regions of different cross sectional shape along the length of its trachea. As already stated, the tracheal bronchus specifically supplies the right cranial lung lobe (cranial and caudal parts).

The pig trachea is circular in cross section and has a range of 32-36 cartilages. The ends of the incomplete cartilaginous rings overlap each other. As already stated, the tracheal bronchus specifically supplies the right cranial lung lobe.

Clinical relevance: tracheal bronchus and intubation

A pig is induced for general anesthesia and will be maintained on gas anesthesia for its procedure. If the tracheal bronchus was inadvertently intubated when passing the endotracheal tube, what single lung lobe will be aerated (and therefore lead to significant complications with anesthesia)?

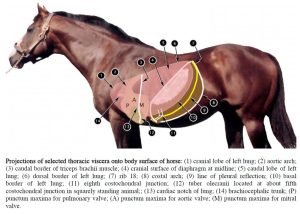

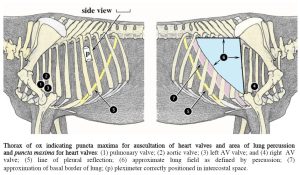

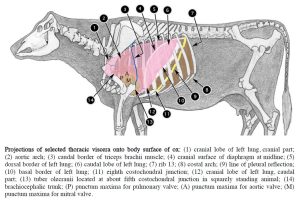

Lung auscultation – horse, ruminant, pig

In the squarely standing ox, horse and pig, the olecranon is at about the level of the fifth costochondral junction. This is a useful clinical landmark for underlying thoracic structures.

Recall, the basal border of the lung is the caudoventral margin of the lungs, primarily traced along the caudal edge of the caudal lung lobe. This basal border location can be approximated on the external thorax to provide a guide as to the caudoventral extent of the lung (keeping in mind the border moves with respiration). In the horse this border passes from the 6th costochondral junction in a sweeping curve through the middle of the 11th rib and ends at the vertebral end of the 16th rib (at the epaxial muscle margin). In the ruminant, this border is steeper, starting again at the 6th costochondral junction, passing through the middle of the 10th rib, and ending at the vertebral end of the 11th intercostal space (i.e. the space caudal to the 11th rib).

For each species then, the surface area for lung auscultation is defined as: 1) cranially, the caudal border of the long head of the triceps muscle, 2) dorsally, the lateral margin of the epaxial mm. and 3) caudoventrally, the basal border of the lung (clinically, this boundary may be approximated by a line drawn from the dorsal last rib to the point of the elbow i.e. the olecranon). It is worth having these boundaries in mind when listening to the chest of a horse or ruminant or pig, to be sure we cover the entire lung area!

- Projections of selected thoracic viscera onto body surface of horse. 2

-

Thorax of ox indicating puncta maxima for auscultation of heart valves and area of lung percussion

and puncta maxima for heart valves. 2

- Projections of selected thoracic viscera onto body surface of ox. 2

Observe: On a cadaver or articulated skeleton, trace the size of the lung area available for auscultation (and percussion) in the ungulates. Be able to define the clinical boundaries for lung auscultation.

Clinical relevance – lung auscultation boundaries

Review videos

CVM Equine lung auscultation video – watch 5:08-6:18

Carnivore lungs – 5 min, watch until 7 min

Ungulate lung comparison – 11 min

Terms

| Carnivore |

|

| Features | Comments |

| Apex of lung | the cranial end |

| Base of lung | the caudal end |

| Left lung | |

| Cranial lobe of left lung | with cranial and caudal parts |

| Caudal lobe of left lung | |

| Right lung | |

| Cranial lobe of right lung | |

| Middle lobe of right lung | |

| Caudal lobe of right lung | |

| Accessory lobe of right lung | |

| Root of lung | |

| Hilus of lung | |

| Cardiac notch | A feature of the right lung |

| Trachea | |

| Tracheal cartilage | |

| Carina | Viewed luminally |

| Principal bronchus | Left and right |

| Lobar bronchus (pl. bronchi) | Left and right, to each lung lobe |

| Ungulate |

|

| Features | Comments |

| Apex of lung | the cranial end |

| Base of lung | the caudal end |

| Left lung | |

| Cranial lobe of left lung | |

| Caudal lobe of left lung | |

| Right lung | |

| Cranial lobe of right lung | |

| Middle lobe of right lung | ruminant and pig, not present in horse |

| Caudal lobe of right lung | |

| Accessory lobe of right lung | |

| Root of lung | |

| Hilus of lung | |

| Cardiac notch | present left and right lungs |

| Trachea | |

| Tracheal cartilage | |

| Tracheal bronchus | ruminant and pig, not present in horse |

| Carina | Viewed luminally |

| Principal bronchus | Left and right |

| Lobar bronchus (pl. bronchi) | Left and right, to each lung lobe |

| Basal border of lung | |

| Lung auscultation boundaries | |