Lab 12A: Midgut and Hindgut of the Ungulates

Learning Objectives

- Identify the different parts of the duodenum in each of the ungulate species.

- Identify the jejunum in the ungulate species and the associated structures.

- Identify the ileum in the ungulate species and the structures associated with its junction with the large colon.

- Describe the anatomy of the cecum in the horse.

- Identify the different parts of the large colon in the different ungulate species, and note key differences between species.

- Describe the pathway of ingesta from oral to aboral in all ungulate species.

Lab Instructions

For this lab, you will be studying instructor prosections and wet and dry specimens around the lab. Please refer to these materials when reading this guide and be sure to use a diversity of materials in your studies. Because these materials are limited, please feel free to jump to different sections of this lab guide to make the most of your time in lab. This guide is organized by species, allowing you to quickly scroll from section to section rather than having to read through text regarding a species that you may not be standing at.

The Gastrointestinal Tract, a Review

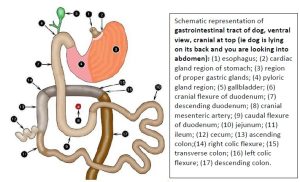

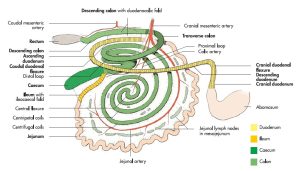

Observe: Refer to figure below and refresh your knowledge of the ‘simple’ canine gastrointestinal tract. In particular, note the relationship of the various parts of the GIT to the root of the mesentery (identified by the cranial mesenteric a. in image).

- Gastrointestinal tract of dog. 2

- Intestinal tract of the dog. 8

Recall the 4 basic rules of arrangement related to the root of the mesentery:

- Descending duodenum on the right

- Descending colon on the left

- Caudal duodenal flexure is caudal to root of mesentery

- Transverse colon passes right to left, cranial to the root of mesentery

Our large animal ungulate species have modified certain parts of the GIT to allow for fermentative digestion of their plant-based diet. The stomach (“plan A”) and large intestine (“plan B”) represent two modified locations where food passage slows down for this digestion to occur. Each species chooses plan A or plan B and sometimes a combination of both.

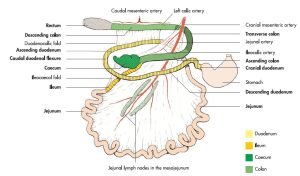

Although the ungulate GITs appear different, they all have a common basic plan, as represented by the digestive tract of the dog. The modifications at first appear complex, but they become less complex when approached from a comparative point of view. The image below is a good one to return to when comparing GI tracts.

The individual species modifications, followed by a guided tour of the GIT, are outlined in the following sections for each species. Review for horse, ruminant and pig, moving from one species to the next as you study the content.

- Comparative schematic of modifications of large intestine, right caudolateral view. 2

- Intestinal tract of the horse. 8

- Intestinal tract of the ox. 8

- Intestinal tract of the pig. 7

- Intestinal tract of the dog. 8

Watch: In this short series of videos, Dr. Hudson describes how each ungulate species modified the “dog plan” of their gastrointestinal tract (GIT) layout.

- Horse GIT modifications – 8 min

- Ruminant GIT Modifications – 6 min

- Pig GIT Modifications – 4 min

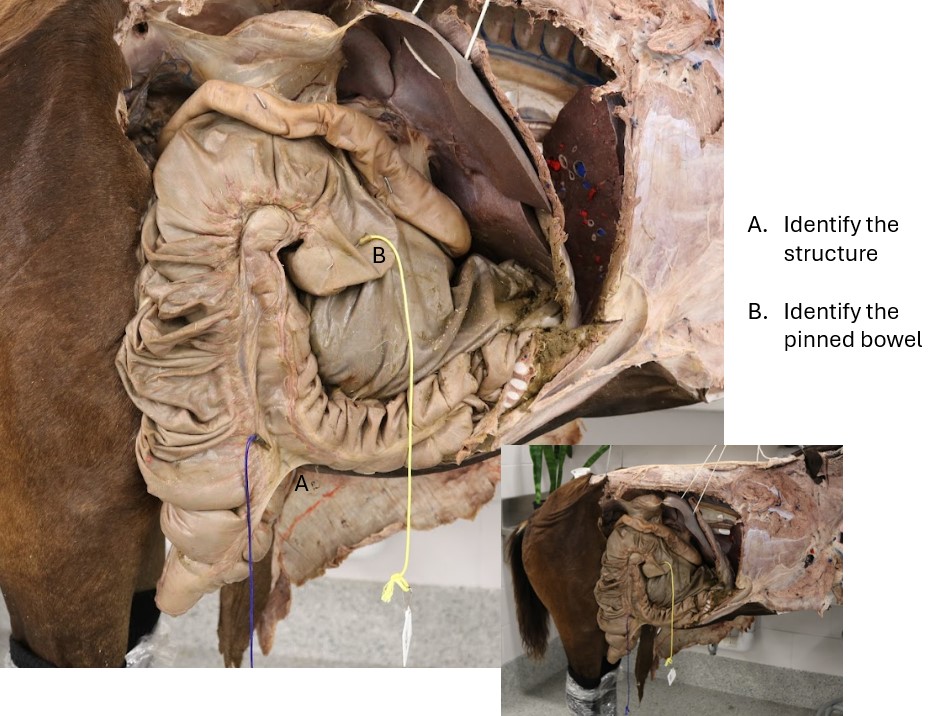

Horse GI Tract

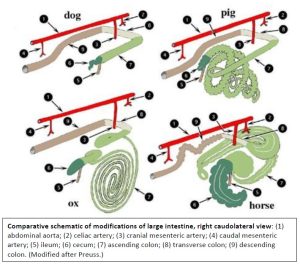

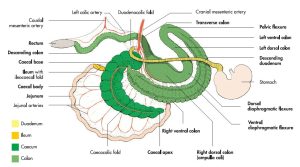

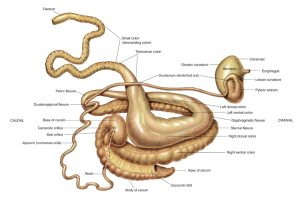

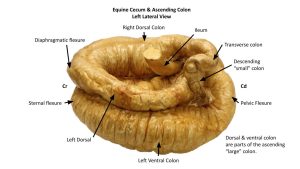

Modifications of the horse involve four segments: stomach, cecum, ascending colon, and descending colon. The fundus of the horse stomach has slightly expanded to form a dome-like saccus cecus (blind sac). Much more significant modifications occur in the large intestine (i.e. Plan B). The cecum is greatly enlarged and has haustra (sacculations) to promote mixing and kneading of ingesta. Four tenia (distinct bands of muscular tissue in the outer layer of the tunica muscularis) also aid in strong cecal contractions. The ascending colon (clinically referred to as the large colon) elongates into a large loop, with dorsal and ventral limbs. Haustra and tenia are present along certain parts of the ascending colon and the last part becomes greatly dilated. The descending colon (clinically referred to as the small colon) elongates and becomes distinctly haustrated and has two tenia.

Pretend that the cadaver has just ingested you and trace your course through the intestinal tract of the horse, the pig, and the ruminant. The State Fair has nothing on the rides you are about to take. In addition to the cadaver, refer to dry and plastinated specimens as well; the ride ticket covers all options and unlimited goes!

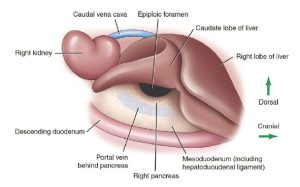

Starting on the right side of the cadaver, from the stomach, the duodenum turns cranially at the sigmoid flexure and then immediately caudally at the cranial flexure to become the descending duodenum. It passes over and around the base of the cecum (ie caudal to the root of the mesentery) as the caudal duodenal flexure and then continues as the ascending duodenum on the left. While still on the right side, let’s check out an important peritoneal structure:

Observe: On one of the horse cadavers, and from the right side, slide your hand under the right lobe of the liver to locate the caudate process (lobe) and then slowly slide your hand into the space between the caudate process and the descending duodenum, with fingers aiming towards the dorsal midline of the body. You should locate a slit-like, natural opening at the dorsal border of the lesser omentum, large enough to accommodate one or more fingers. Congratulations, you have just found the epiploic foramen, and you now have your finger(s) in the omental bursa.

The peritoneal cavity proper communicates with the omental bursa through this opening. The epiploic foramen is principally bounded by the caudate process (lobe) dorsally, by the portal vein cranially and the hepatoduodenal ligament (or gastropancreatic fold!) ventrally.

- Location of the epiploic foramen in the horse. 9

Observe: Before moving on, make sure you’ve identified in Horse: epiploic foramen and describe its boundaries.

Clinical Application

-

Transverse view of the equine abdomen illustrating the boundaries of the epiploic foramen (A) and an entrapped loop of jejunum (B).

9

Observe: Move around to the left side, pick up the ascending duodenum and trace it cranially to its transition at the duodenojejunal flexure to the jejunum. Identify the duodenocolic fold just oral to this flexure, a thin connecting peritoneum between the duodenum and the proximal (oral) end of the descending colon that prevents further exteriorization of the small intestine during an exploratory surgery. Pull out a loop of jejunum, which is easily distinguished from the descending colon by its smooth wall appearance.

Note the long mesojejunum that gives the bowel a great deal of mobility and allows the jejunum to get into every little nook and cranny that becomes available, including the epiploic foramen. Such a long mesentery also predisposes the jejunum to becoming twisted on its mesentery, like a swing on its chains. Twisting of the mesentery, and vessels contained therein, can greatly compromise venous and lymphatic return, and the arterial supply to the affected bowel segment. This type of twist is termed a volvulus, and is one form of potentially fatal colic in the horse.

- Schematic representation of gastrointestinal tract of horse, ventral view. 2

- Intestinal tract of the horse. 8

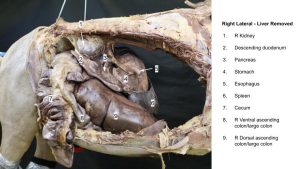

- Right topography – liver removed

- Duodenocolic fold

- Duodenocolic fold

Observe: If you pull out on the jejunum, you can see that it is attached at the root of the mesentery, which surrounds the cranial mesenteric artery.

Examine the vascular pattern in a segment of mesojejunum.

Neighboring jejunal arteries are joined by arcuate branches, which in turn give rise to a secondary set of smaller, branching arteries that supply the gut wall. Thus, there are arterial anastomoses which may protect the gut from infarction in case of arterial blockage.

The jejunum (about 60-70 feet in length) is continued distally by the ileum, which will be seen later.

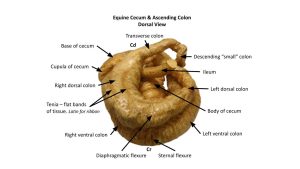

Observe: Move back to the right side and locate the base of the cecum.

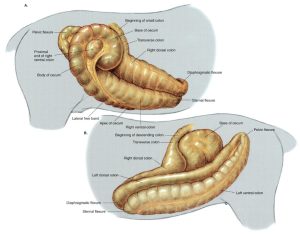

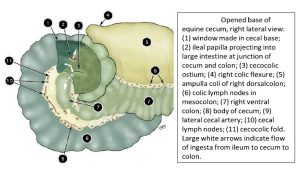

What appears to be the most cranioventral part of the cecal base is actually the initial part of the ascending colon (by embryological definition), that is sharply curved like a hook.. That being said, clinically, that initial part of the ascending colon is considered to be functionally part of the cecum and is referred to clinically and in the veterinary literature as the cupula of the cecum. Impactions of the cecal cupula have been reported. The body of the cecum continues in a comma-shaped curve to the apex, which is located near the xiphoid cartilage. Note the haustra and tenia of the cecum. The cecum has four tenia.

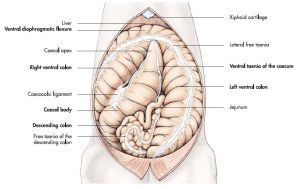

- Equine cecum, large (ascending) colon, and transverse colon in situ. 30

- Caecum and colon of the horse in situ. 7

- Opened base of the equine cecum. 2

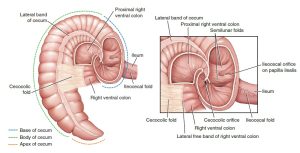

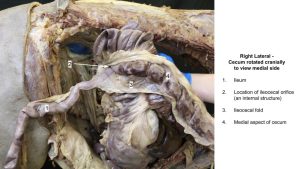

Observe: Reach around the caudal part of the cecal base and locate the ileum entering the cecum at its dorsomedial aspect. The ileum is attached to the cecum by the ileocecal fold, which continues as the dorsal tenial band on the cecum. The transition from jejunum to ileum is defined by the proximal edge (i.e. oral end) of the ileocecal fold. There is typically no antimesenteric ileal artery in the horse. Grasp the ileum and palpate its thick-walled structure, as compared with that of the jejunum.

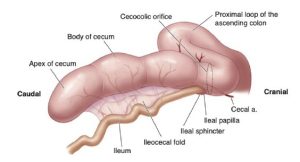

The ileum becomes more muscular as it approaches the cecum, and ileal impaction is a frequent cause of non-strangulating obstruction in the small intestine of the adult horse. The ileum discharges into the cecum at the ileocecal orifice. The cecum empties into the ascending (large) colon at the cecocolic orifice.

- The equine cecum showing the base, apex, and body, as well as ileocecal and cecocolic orifice. 9

- Cecum

- Ileocecal fold

Observe: Before moving on make sure you’ve identified the following in the horse: descending duodenum, caudal duodenal flexure, ascending duodenum, duodenojejunal flexure, duodenocolic fold, jejunum, mesojejunum, root of mesentery, ileum, ileocecal fold, ileocecal orifice, cecum (base, body, apex, cupula), haustra, tenia, cecocolic orifice (ostium).

Clinical Application

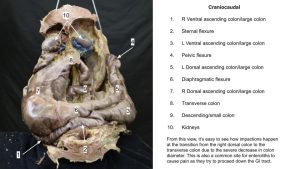

Observe: Trace the lateral tenial band of the cecum onto the beginning of the ascending (large) colon.

This peritoneal connection is the cecocolic fold, a critical landmark in surgery. From the cecum, the right ventral colon continues cranially to the sternal flexure near the xiphoid and is continued along the left side as the left ventral colon. The entire ventral colon is haustrated, with four tenia. The diameter of the colon becomes reduced as it approaches the pelvic flexure, and the haustrations play out. Here, the left ventral colon turns back on itself to become the left dorsal colon.

-

The ascending colon as examined at necropsy. The right ventral colon with its sacculations (A). The medial free teniae of the left ventral colon (B ). The pelvic flexure (C ). The narrow left dorsal colon (D ). The wide right dorsal colon (E ). Note the apex of the cecum at the bottom left corner

of the photo. 9

- Isolated stomach and intestines of the horse. 30

- Equine cecum, large (ascending) colon, and transverse colon in situ. 30

Observe: Draw the pelvic flexure out of the abdomen, and find the single palpable tenia in its mesenteric border. Trace the left dorsal colon cranially to the diaphragmatic flexure.

Here, the colon turns caudodorsally as the right dorsal colon, which has the greatest diameter of any part of the colon, forming a sac-like expansion known as the ampulla coli. Locate the right colic flexure, which is the junction of the right dorsal and transverse colon. Here the diameter is reduced so drastically that the area is a common site for impaction.

In contrast with the haustrated ventral colon, the entire dorsal colon is smooth; however, tenia are present. Beginning with the single one, present in the mesocolon of the left dorsal part, two more appear over the diaphragmatic flexure and continue onto the right dorsal colon, which therefore has three tenia.

Note the mesocolon between the left dorsal and ventral parts of the colon. The pelvic flexure is the apex of that long, free loop of ascending colon. Thus, the large colon is free to twist around on its mesentery, producing a volvulus of the large colon. It may also simply be displaced from its normal position. If that weren’t enough, there is a reduction in bowel diameter in the pelvic flexure-left dorsal colon segment, so this area is also a natural place for bowel impaction.

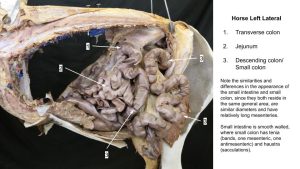

The transverse colon, passing right to left is continued by the descending (small) colon, which may be distinguished from small intestine via palpation per rectum by its antimesenteric tenia (there is also a mesenteric tenia). The descending colon usually lies mixed with loops of jejunum in the left dorsal part of the abdominal cavity.

Distinguishing parts of the intestine during palpation per rectum may rely on detecting teniae. In summary, the number of tenia per part is: small intestine 0, cecum 4 (the ventral cecal band most commonly palpable), right ventral colon 4, left ventral colon 4, pelvic flexure and left dorsal colon 1, right dorsal colon 3, transverse colon 2, and descending colon 2 (how about dialing 444 1322?!). During palpation per rectum of a normal horse the caudal loops of jejunum, pelvic flexure area, descending colon and perhaps the cecal base and ventral cecal band can be distinguished, plus a few other abdominal/urogenital tract organs.

- The blood supply to the equine small colon. 9

- Transverse colon

- Descending colon

Observe: Before moving on make sure you’ve dentified the following in the Horse: cecocolic fold; ascending (large) colon: right ventral colon, sternal flexure, left ventral colon, pelvic flexure, left dorsal colon, diaphragmatic flexure, right dorsal colon; transverse colon; descending (small) colon; mesocolon; haustra; tenia.

Clinical Application

Horse ascending colon practice question

Ruminant GI Tract

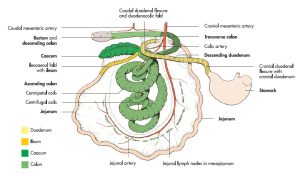

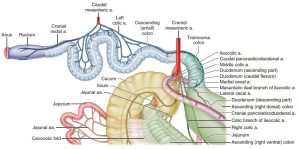

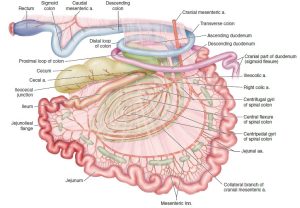

Modifications of the ruminant involve three segments: stomach, cecum, and ascending colon. Both the stomach and large intestine are significantly modified in the ruminant (ie Plan A and Plan B). The more proximal (oral) part of the embryonic stomach primordium becomes greatly enlarged and subdivides into three compartments, all lined with a nonglandular, stratified squamous epithelium. The distal part of the stomach primordium develops into the glandular compartment. Note: ruminants do not have four stomachs; they have one stomach subdivided into 4 compartments (previously studied). The cecum enlarges somewhat, but without haustrations or tenia, and the ascending colon, like that of the pig, forms a long spiral loop. Unlike the pig, however, the ruminant cecum is on the right side, so a proximal loop is necessary to get the colon over on the left side of the mesojejunum. A distal loop is also needed to bring it back to the right so the ascending colon can join the transverse colon at the right colic flexure.

Pretend that your cadaver has just ingested you and trace your course through the intestinal tract of the horse, the pig, and the ruminant. The State Fair has nothing on the rides you are about to take. In addition to the cadaver, refer to dry and plastinated specimens as well; the ride ticket covers all options and unlimited goes!

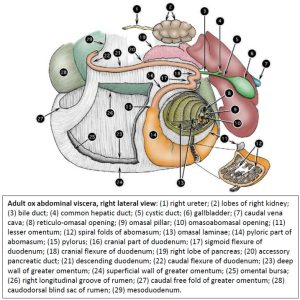

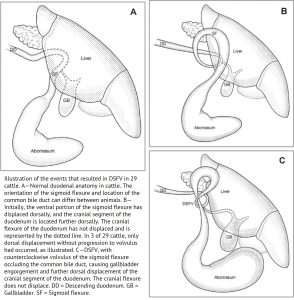

Beginning at the pylorus, the duodenum courses cranially as the cranial part, during which it makes a sigmoid flexure near the liver, then turns caudally at the cranial flexure to become the descending duodenum. At the caudal duodenal flexure, the duodenum turns cranially as the ascending duodenum to the duodenojejunal flexure. Here, the peritoneal attachment lengthens to support the very long jejunum, which is arranged in many tight, crowded loops in the free edge of the mesentery. Adjacent to the jejunal loops, a series of prominent jejunal lymph nodes should be noted. The mid-distal jejunum and proximal ileum is suspended by a relatively longer portion of mesentery and this is the jejunoileal flange (prone to volvulus, and readily exteriorized during surgery).

The junction of jejunum and ileum is defined by the proximal edge (oral end) of the ileocecal fold, and the ileum can be traced to the ileocecocolic junction.

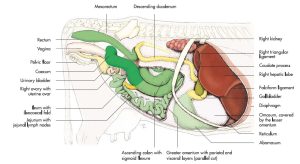

- Adult ox abdominal viscera, right lateral view. 2

- Bovine intestinal tract, right lateral view. 2

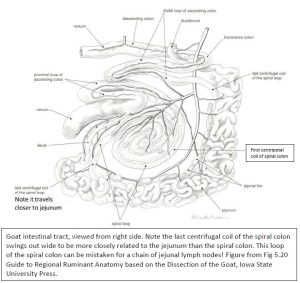

- Goat intestinal tract, viewed from right side.

- Topography of the abdominal and pelvic organs of the cow. 7

- Right view of the bovine gastrointestinal tract and its blood supply. 9

- Anatomy of the bovine cecum and proximal loop of the ascending colon. 9

Observe: Before moving on make sure you’ve identified the following in the Ruminant: duodenum, sigmoid flexure, descending duodenum, caudal duodenal flexure, ascending duodenum, duodenojejunal flexure, jejunum, mesoduodenum, mesojejunum, jejunal lnn., jejunoileal flange, ileum, ileocecal fold, ileocecocolic junction.

Clinical Application

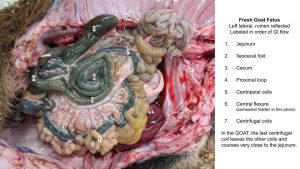

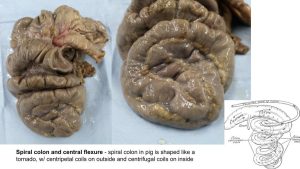

At the ileocecocolic junction, the cecum is directed caudally, and the proximal loop of the ascending colon, which is typically about the same diameter as the cecum, courses cranially, then bends back on itself and turns around the caudal edge of the mesentery to become continuous with the spiral loop. The spiral loop of the ascending colon in the ruminant is actually more coiled (like a garden hose on the ground) than spiraled and becomes adhered embryologically to the left side of the mesojejunum.

The proximal half of the spiral loop is coiling toward the center of the loop and those turns are designated centripetal coils. At the central flexure (homologous to pelvic flexure of horse), the bowel continues spiraling from the center, and the more distal turns are designated centrifugal coils. Note that the last centrifugal coil in the sheep and goat leaves the other coils and courses very close to the jejunum. This longer loop allows more time for water resorption, and the material contained in this coil is typically beginning to be formed into the pellet-type feces, characteristic of the small ruminants (hence the “pearl necklace”). Sheep and goats are better water conservers than cattle, and are thus better adapted for arid conditions.

- Anatomy of the bovine cecum and proximal loop of the ascending colon. 9

- Bovine intestinal tract, right lateral view. 2

- Goat intestinal tract, viewed from right side.

- Goat centrifugal coil

Observe: Because of the accumulation of mesenteric fat, the spiral colon of the adult ruminant is difficult to follow without removal and dissection; thus, it can best be observed (and understood) in the newborn calf.

The distal loop of the ascending colon passes caudally around the mesenteric root and returns the colon to the right side. It lies dorsal to the proximal loop and is typically smaller in diameter. The ascending colon joins the very short transverse colon at the right colic flexure; the transverse colon joins the descending colon at the left colic flexure, and the latter courses caudally to the pelvic cavity. No part of the ruminant colon is haustrated, and no tenia are present.

- Right view of the bovine gastrointestinal tract and its blood supply. 9

- Bovine intestinal tract, right lateral view. 2

- Intestinal tract of the ox. 8

Observe: Identify in Ruminant: cecum, proximal loop of ascending colon, spiral colon, centripetal coils, central flexure, centrifugal coils, distal loop of ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon.

Clinical relevance:

Atresia coli (congenital defect, most often affecting spiral loop of ascending colon); cecal impaction.

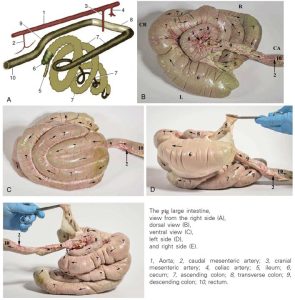

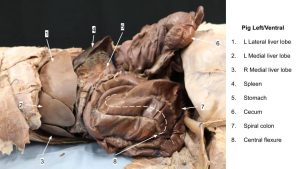

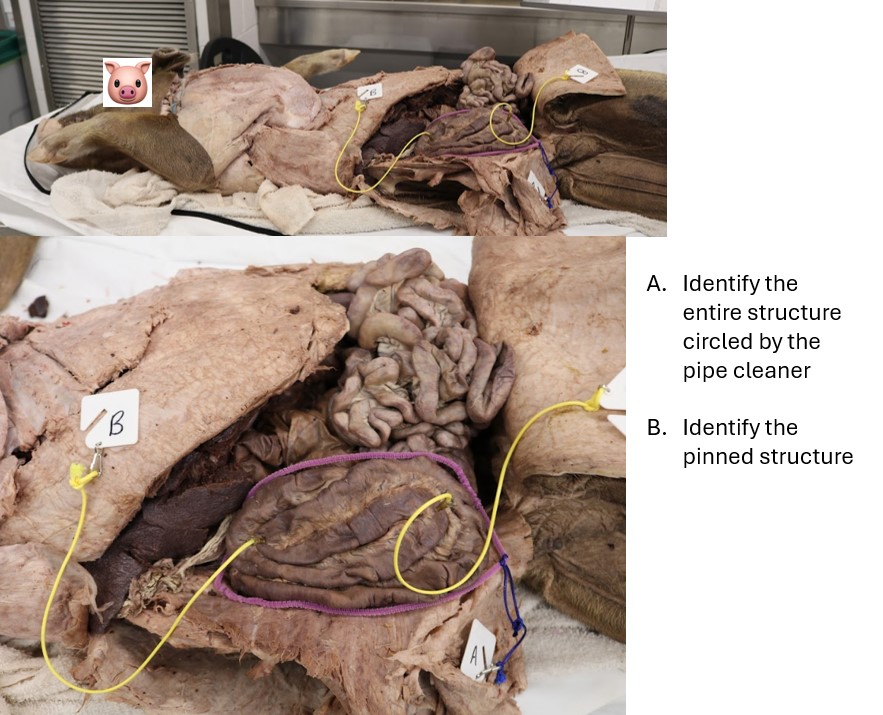

Pig GI Tract

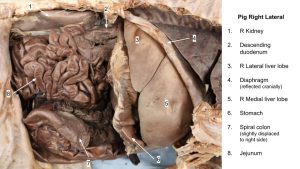

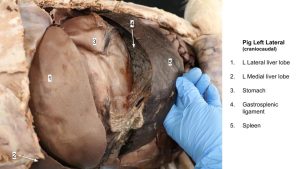

Modifications of the pig involve three segments: stomach, cecum, and ascending colon. Like the horse, the pig’s stomach is only slightly modified in the development of a peculiar out-pocket at the fundus, the gastric diverticulum. The cecum enlarges somewhat and the ascending colon elongates to form a spiral loop (so mostly Plan B for the pig). One unique feature of the pig is that the cecum shifts to the left side, unlike that of other domestic mammals, so that the ascending colon immediately enters the spiral loop on the left side of the mesojejunum. Both the cecum and the first half (centripetal coils) of the ascending colon become haustrated with tenia. The centrifugal coils, however, are smooth, and a distal loop is necessary for the ascending colon to return to the right side for union with the transverse colon.

Pretend that your cadaver has just ingested you and trace your course through the intestinal tract of the horse, the pig, and the ruminant. The State Fair has nothing on the rides you are about to take. After the cadaver, refer to dry and plastinated specimens as well; the ride ticket covers all options and unlimited goes!

Pick up the duodenum and follow it aborally…..The duodenum of the pig follows the typical pathway, and the jejunum is very long, consisting of many small loops supported by a fan-shaped mesentery. Because the cecum and spiral colon usually dominate the left side, the jejunal mass is somewhat crowded into the right half of the abdominal cavity. The ileum, defined by the ileocecal fold, joins the large bowel at the ileocecocolic junction.

- Intestinal tract of the pig. 7

- Pig right lateral

- Gastrosplenic ligament

The branching pattern of the jejunal arteries is rather unique in the pig. Primary jejunal arteries leave the cranial mesenteric and form a series of anastomotic arches that give rise to hundreds (if not thousands) of small secondary branches to form a “brush-like” arterial supply to the bowel wall. As previously noted, the cecum of the pig is on the left. Thus, a proximal loop of the ascending colon is unnecessary, and the spiral loop begins immediately from the cecum.

The cecum and centripetal coils are haustrated with tenia, whereas the smooth centrifugal coils of the ascending colon are concealed within the cone of centripetal coils. However, you can identify the distal loop of the ascending colon as it emerges from the cone and carries the colon caudally around the mesenteric root to the right side to unite with the transverse colon at the right colic flexure. The transverse and descending colon of the pig are not remarkable.

- The pig large intestine. 8

- Spiral colon

- Pig spiral colon

Observe: Make sure you’ve identified the following in the Pig: duodenum, descending duodenum, caudal duodenal flexure, ascending duodenum, duodenojejunal flexure, jejunum, mesoduodenum, mesojejunum, ileum, ileocecal fold, ileocecocolic junction, cecum (haustra, tenia), spiral colon, centripetal coils (haustra, tenia), central flexure, centrifugal coils, distal loop of ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon.

Clinical Application

Review Videos

In this short series of videos, Dr. Hudson describes how each ungulate species modified the “dog plan” of their gastrointestinal tract (GIT) layout.

- Horse GIT modifications – 8 min

- Ruminant GIT Modifications – 6 min

- Pig GIT Modifications – 4 min

Large intestine models:

- Horse large intestine – 17 min

- Ruminant and pig large intestine – 7 min

- Cow spiral colon cadaver and model – 4 min

Key Terms

| Term | Species/Notes |

| Duodenum | All |

| Cranial duodenum | Ruminant |

| Sigmoid flexure of duodenum | Ruminant |

| Mesoduodenum | All; mesentery of the duodenum |

| Descending duodenum | All |

| Caudal duodenal flexure | All |

| Ascending duodenum | All |

| Duodenojejunal flexure | All |

| Duodenocolic fold | Horse |

| Jejunum | All |

| Mesojejunum | All; mesentery of the jejunum |

| Jejunoileal flange | Ruminant |

| Jejunal lymph nodes | Ruminant |

| Root of mesentery | Surrounds the cranial mesenteric a. |

| Ileum | All |

| Ileocecal fold | All |

| Ileocecal orifice | Horse |

| Ileocecocolic junction/orifice | Ruminant, pig |

| Cecum | All |

| Base of cecum | Horse |

| Body of cecum | Horse |

| Apex of cecum | Horse |

| Cupula | Horse |

| Cecocolic orifice | Horse |

| Haustra | All |

| Tenia | All |

| Cecocolic fold | Horse |

| Ascending colon | |

| Right ventral colon | Horse |

| Sternal flexure | Horse |

| Left ventral colon | Horse |

| Pelvic flexure | Horse |

| Left dorsal colon | Horse |

| Diaphragmatic flexure | Horse |

| Right dorsal colon | Horse |

| Transverse colon | All |

| Mesocolon | All; mesentery of the colon |

| Proximal loop | Ruminant |

| Spiral colon | Ruminant, pig |

| Centripetal coils | Ruminant, pig |

| Central flexure | Ruminant, pig |

| Centrifugal coils | Ruminant, pig |

| Distal loop | Ruminant, pig |

| Descending colon | All |

Example Practical Exam Questions