Lab 13A: Accessory GI Organs of the Ungulate and Abdominal Topography

Learning Objectives

- Review the comparative anatomy of the accessory organs of the ungulate gastrointestinal tracts; including the liver, pancreas, and spleen.

- Describe the topography of the abdominal viscera as viewed from left and right sides and correlate this to physical examination findings when percussing and auscultating.

Lab Instructions

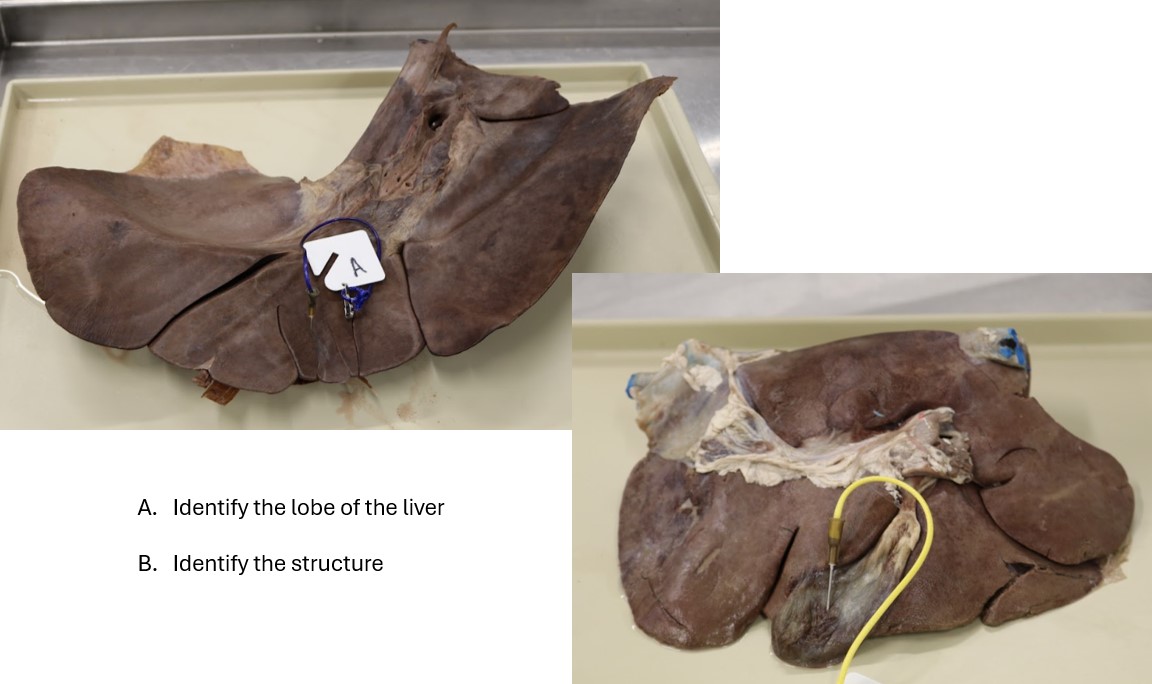

The Liver, epi table (all species)

Please review wet liver specimens for study and comparison between species.

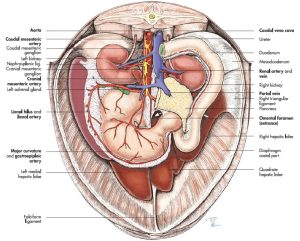

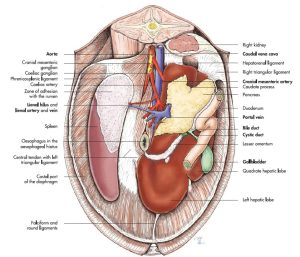

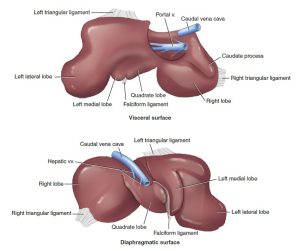

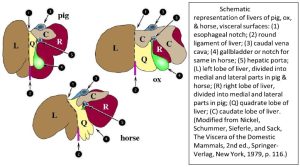

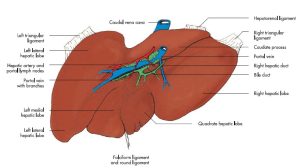

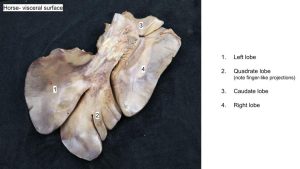

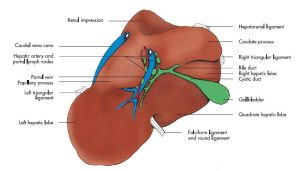

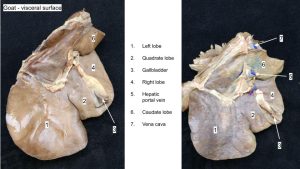

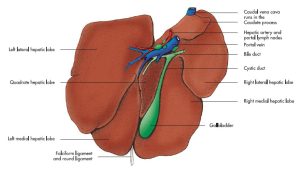

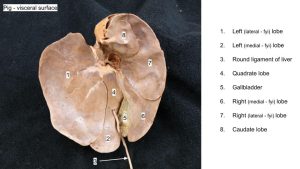

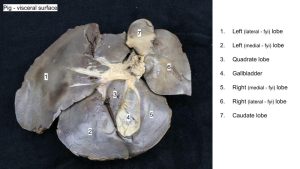

Observe: Place livers of the different species on the table and compare them. Turn them, visceral side up, with the rounded border facing away from you. Locate: (1) the notch for the round ligament; (2) the point where the caudal vena cava crosses the rounded border of the liver; (3) the gallbladder (in the horse, the distinct notch where the gallbladder would have been); and (4) the hepatic porta (where the portal vein and hepatic artery enter the liver). Observe that the caudate process is excavated (renal impression) to “caress” the cranial extremity of the right kidney.

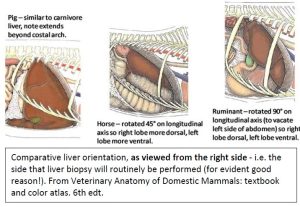

The liver of the pig, unlike that of other domestic mammals, does not contact the right kidney, so there is no distinct renal impression.

The lobe projecting caudally toward you, that is dorsal to the porta, is the caudate lobe, which in the ruminant has two parts, a caudate process and a papillary process. The caudate process is especially large in the ox. The horse and the pig do not have a papillary process.

The round ligament enters the liver between the left lobe and the quadrate lobe. The left lobe, in the pig and the horse is divided into medial and lateral parts. The gall bladder tucks in between the right lobe, (divided into medial and lateral parts in the pig), and the quadrate lobe. As you recall, the portal vein receives blood from the stomach, spleen, pancreas, and intestines that is laden with absorbed nutrients (except triglycerides), and may also contain infectious organisms and/or toxic material. The liver can metabolically convert these nutrients and store and release over time in the appropriate form to the general circulation. Similarly, the liver, functioning as a filter, can capture infectious organisms and help detoxify certain toxins. As a result, the liver is affected directly by many toxins, and abscesses of the liver are not uncommon, especially in feedlot cattle. The hepatic artery delivers the liver’s nutritional blood supply.

- Intrathoracic abdominal organs of the horse. 7

- Intrathoracic abdominal organs of the ox. 7

- Lobes of the horse liver. 9

- Comparative liver orientation, as viewed from the right side. 7

- Livers of the pig, ox, and horse. 2

Blood that enters the liver through the portal vein and hepatic artery returns to the general circulation through the hepatic veins to the caudal vena cava. The parenchyma of the pig liver is supported by a pronounced fibrous stroma, which is evidenced on the surface by the more obvious lobulated appearance of the pig liver. Depending on the lifestyle and husbandry of the animal, the livers of domestic ungulates frequently bear the scars of parasitic larval migrations.

Observe: Identify in all species: gall bladder (NOT present in horse), liver lobes – left, right, quadrate, caudate, caudal vena cava, portal vein.

Horse liver

- Liver of the horse. 7

- Horse liver

- Horse liver

Ruminant liver

- Liver of the ox. 7

- Goat liver

- Calf liver

Pig liver

- Liver of the pig. 7

- Pig liver

- Pig liver

Clinical Application

Pancreas, all species

Locate the pancreas near the portal vein, in the mesoduodenum. FYI – In the horse and pig, the pancreas completely surrounds the portal vein, forming the annulus pancreatic. Like the liver, the exocrine part of the pancreas develops as an outgrowth of the embryonic gut (duodenum); however, in the case of the pancreas, there are two primordial buds, dorsal and ventral. The dorsal bud grows into the mesoduodenum (becoming the right lobe), while the ventral bud is closely associated with the developing liver in the ventral mesogastrium (becoming the left lobe). By definition, the dorsal bud (right lobe) forms the accessory pancreatic duct and the ventral bud (left lobe) forms the pancreatic duct. The two buds grow together near the cranial flexure of the duodenum to form the body of the pancreas, and their individual duct systems anastomose with one another. Because only one excretory duct is really needed, some animals choose to do away with the other one. If one day you need to know exactly which ducts remain and what papillae they empty at in the duodenum, please feel capable of looking that information up :). Note that a major duodenal papilla is expected in all species studied, for discharge of bile from the bile duct.

Spleen – all species

Observe: Locate the spleen against the left abdominal wall, usually protected by ribs.

Although its shape differs considerably in our domestic mammals, its position is similar. Having developed in the dorsal mesogastrium, the spleen is closely associated with the greater curvature of the stomach (well I guess that makes sense and once again knowing a little developmental anatomy goes a long way).

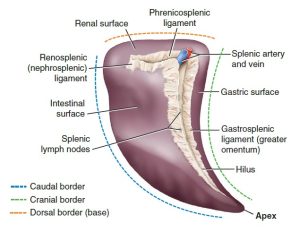

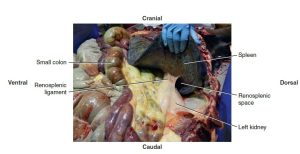

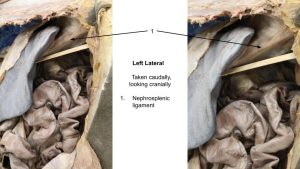

In the horse, note/palpate the fibrous connection between the spleen and the left kidney. This is the nephrosplenic ligament, a site of entrapment of the ascending colon (i.e. the large colon). Also note the attachment of the spleen to the stomach – this is the gastrosplenic ligament, which can entrap and strangulate small intestine when it passes through a rent in this structure.

- Equine spleen (visceral surface) and associated ligaments. 9

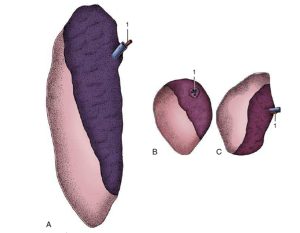

- The spleens of (A) cattle, (B) sheep, and (C) goats. 8

- Normal equine nephrosplenic (renosplenic) ligament identified during routine necropsy.

- Gastrosplenic ligament

- Nephrosplenic ligament

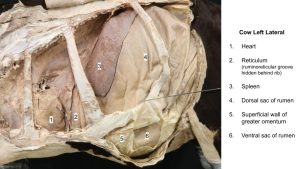

- Left cow topography

Observe: Identify the following in the horse cadaver: nephrosplenic ligament, gastrosplenic ligament

Clinical Application

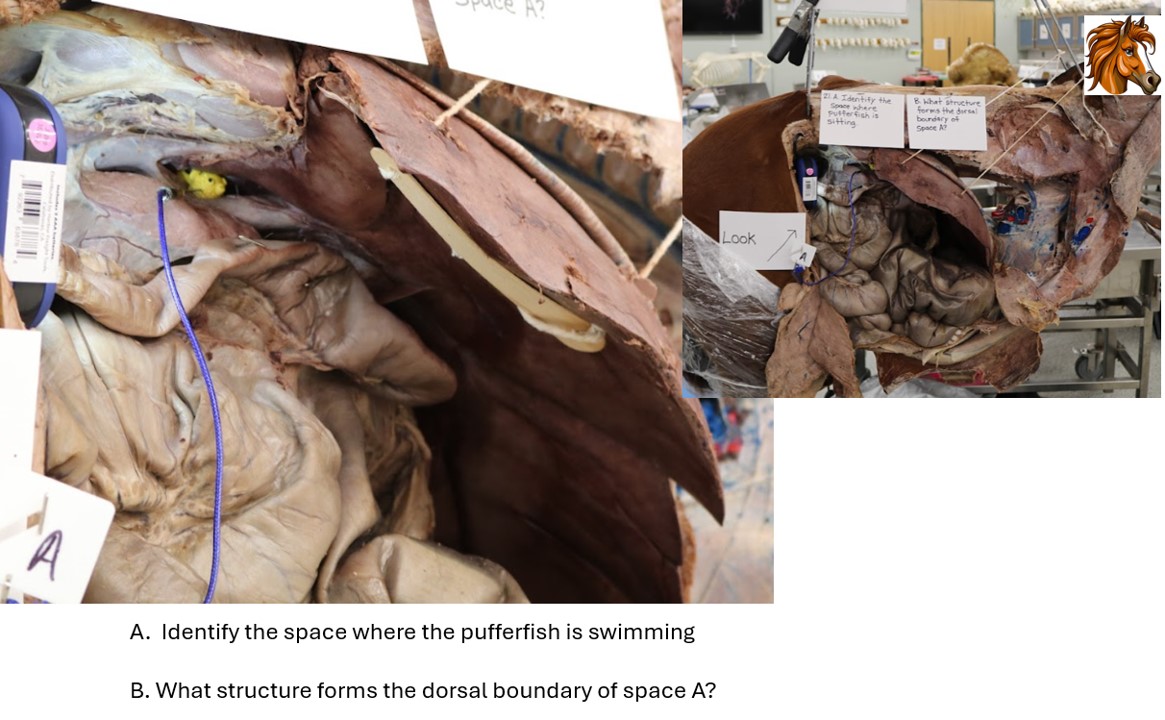

Abdominal Topography

Now that we have an understanding of the abdominal cavity and its viscera, the last step is to picture it all together and visualize its relative location in the abdomen. Before any procedures of the abdomen are performed, or imaging is interpreted, the veterinarian must know what is expected where.

Recall that the normal peritoneal cavity is a potential space, containing only a thin layer of peritoneal fluid, spread out around the organs. (How much fluid? Just enough.)

Observe: For each species, read the topography description, study the figures, and visualize the viscera in their correct location in the cadavers. You may have to move a few parts of the intestine back into its spot after it has been jostled around for tracing.

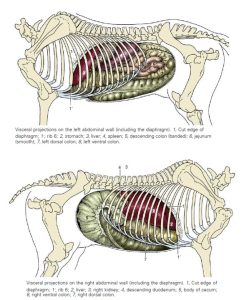

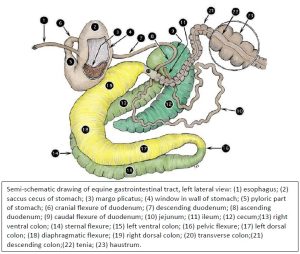

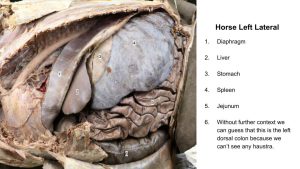

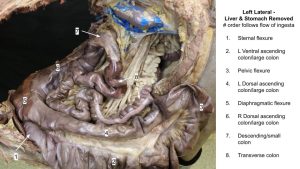

Left Side of the Horse

Most of the dorsal flank area is occupied by a mixture of jejunum (smooth wall) and descending colon (haustrated) resting on the ascending colon. The pelvic flexure of the colon may be noted near the pelvic inlet in the left flank. Part of the spleen may be seen projecting from under the last rib. With the diaphragm reflected, in the cranial aspect of the abdomen you should be able to see the spleen, the greater curvature of the stomach, and part of the left lobe of the liver.

- Horse abdominal topography. 8

- Ventral and dorsal view of the horse abdomen. 8

- Semi-schematic drawing of equine gastrointestinal tract, left lateral view. 2

- Left topography

- Left topography, organs removed

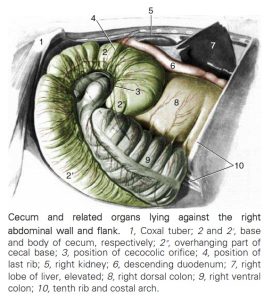

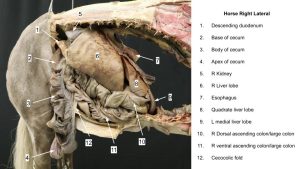

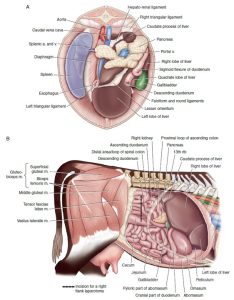

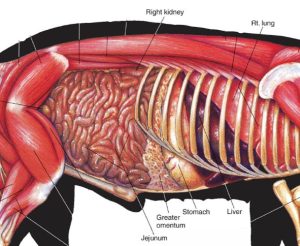

Right Side of the Horse

The upper right flank area is occupied by the base of the cecum, which more ventrally is continuous with the body of the cecum. Part of the right ventral colon may also be noted in the concavity of the cecum, which inclines medially. With the diaphragm reflected, you should be able to see the descending duodenum, the right kidney, the right lobe of the liver, and more of the ascending colon.

- Cecum and related organs lying against the right abdominal wall and flank. 8

- Right topography

- Right topography – liver removed

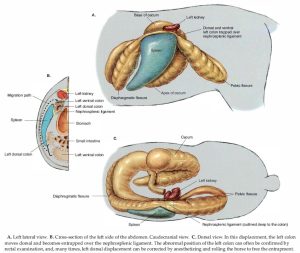

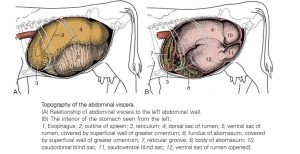

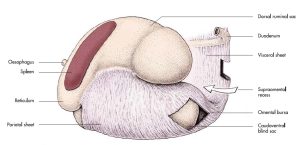

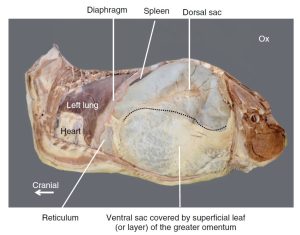

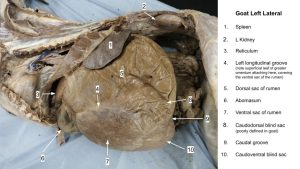

Left Side of the Ruminant

In the adult, almost the entire left side of the abdominal cavity (and more) is occupied by the rumen, with the dorsal sac located in the paralumbar fossa. The ventral sac is covered by the superficial wall of the greater omentum. With the diaphragm reflected, you should be able to see the spleen, the cranial sac of the rumen, and the reticulum.

In the newborn calf, the rumen is small and deflated. Most of the left flank is occupied by small intestine that may be partly covered by the greater omentum, which attaches ventrally to the abomasum. Depending on the amount of sublumbar, retroperitoneal fat, you may also be able to identify the left kidney. With the diaphragm reflected, you should be able to see the spleen and the reticulum.

- Topography of the abdomen of the cow, left side. 8

- Greater omentum of a ruminant, left lateral. 7

- Bovine thoracic and abdominal cavities, left lateral view. 16

- Left cow topography

- Goat rumen

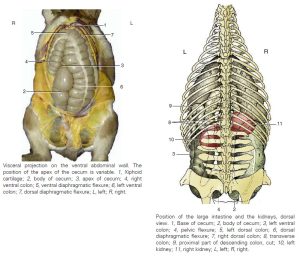

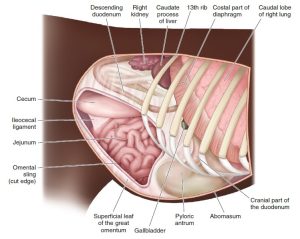

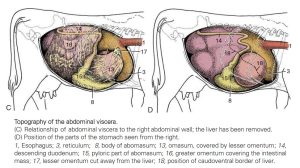

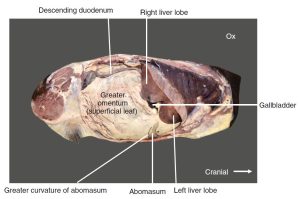

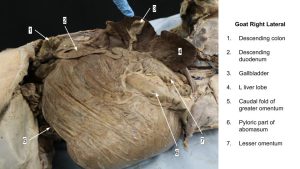

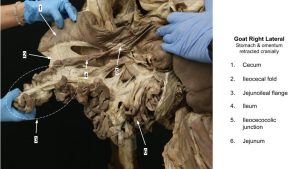

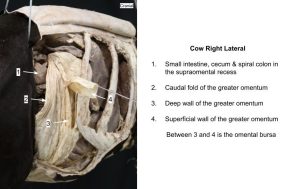

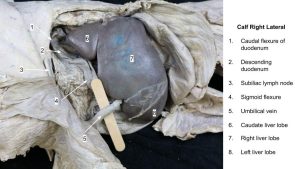

Right Side of the Ruminant

Typically, the only organ identifiable on initial reflection of the parietal peritoneum is the descending duodenum. Dorsal to the duodenum is the mesoduodenum, which contains fat and the right lobe of the pancreas; ventral to the duodenum is the superficial wall of the greater omentum, which typically contains a great deal of fat. The caudal free fold of the greater omentum may also be identified. With the diaphragm reflected, you should be able to see the liver and gallbladder, part of the abomasum, and the omasum, which is covered by the lesser omentum.

- The location in situ (A) and anatomy (B) of the liver. 9

- Topographical anatomy of the right abdomen of a standing adult cow. 9

- Topography of the abdominal viscera, right side. 8

- Bovine thoracic and abdominal cavities, right lateral view. 16

- Goat epiploic foramen

- Goat omentum, right side

- Goat right lateral

- Right omentum

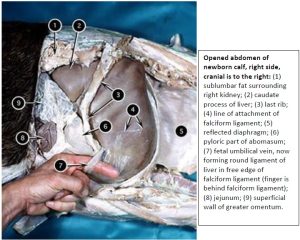

In the newborn calf, most of the right flank area is occupied by the intestines, but the large liver of the newborn projects caudal to the last rib. Ventral to the costal arch, you can see the abomasum, which is crossed by the large, flat round ligament of the liver contained in the free edge of the falciform ligament. In the fetus, this is the umbilical vein, which transports oxygenated blood into the fetus from the placenta. The notch for the entry of the round ligament (atrophied umbilical vein) into the liver marks the division between the quadrate and left lobes.

Observe: Identify in calf: round ligament of liver/umbilical vein

- Opened abdomen of newborn calf. 2

- Calf right lateral

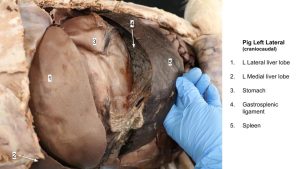

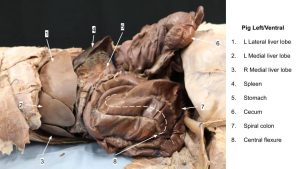

Left Side of the Pig

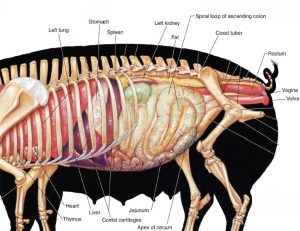

Unlike that of other adult domestic ungulates, the cecum of the pig is typically located near the dorsal part of the left flank and closely associated with the cecum is the spiral part of the ascending colon. More ventrally, you can see many loops of the jejunum (smooth) and more haustrated coils of the spiral colon. With the diaphragm reflected, you should be able to see the left kidney, the spleen, the stomach, and the liver.

- Abdomen of the pig, left side. 30

- Gastrosplenic ligament

- Spiral colon

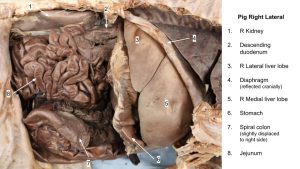

Right Side of the Pig

In the non-pregnant animal, most of the caudal part of the abdominal cavity is filled with intestines, primarily jejunum. Part of the liver and the gallbladder project beyond the costal arch. With the diaphragm reflected, you should be able to see the right kidney and more liver.

- Abdomen of the pig, right side. 30

- Pig right lateral

Review Videos

Right side fresh horse topography – 5 mins – Please note, this is a freshly euthanized animal at necropsy, and not all parts of the duodenum are visible to be discussed.

Right side fresh cow topography– 14 mins – Please note, this is a freshly euthanized animal at necropsy, and the sequence of intestine segments is not presented in its entirety. This video has some embedded quizzes. Please let Lindsey know how you like this feature.

These videos were produced in 2020:

- Equine GIT review Sp20, 21 mins

- Goat GIT review Sp20, 13 mins

- Pig GIT review Sp20, 9 mins

The below is a list of videos snipped from much longer combined species versions that were produced in 2017. Some terms mentioned we no longer focus on and use your current Abdomen Lab Guide terms list to direct your knowledge base.

- Abdomen.topog.Goat.Sp17 – 11 mins

- Abdomen.topog.Calf.Sp17 – 10 mins

- Abdomen.topog.Pig.Sp17 – 7 mins

- Abdomen.GITrace.Horse.Sp17 – 43 mins

- Abdomen.GITrace.Goat.Sp17 – 23 mins

- Abdomen.GITrace.Calf.Sp17 – 22 mins

- Abdomen.GITrace.Pig.Sp17 – 20 mins

- Livers.epitable.Sp17 – 19 mins, and note, no need to identify liver hilus structures (vessels, bile duct), which are covered in some detail in this video.

Key Terms

| Term | Species/Notes |

| Liver | All |

| Right lobe | All |

| Left lobe | All |

| Quadrate lobe | All |

| Caudate lobe | All |

| Papillary process | Ruminant |

| Caudate process | All |

| Round ligament | All |

| Gallbladder | Ruminant, pig |

| Caudal vena cava | All |

| Pancreas | All |

| Spleen | All |

| Nephrosplenic ligament | Horse |

| Gastrosplenic ligament | Horse |

| Abdominal topography | Be able to recognize what we should expect to find on the left and right sides of each species |

Example Practical Exam Questions