Learning Objectives

- List and identify the osseous boundaries of the pelvic inlet and outlet in the domestic species.

- Describe the pelvic canal and its boundaries.

- Define and identify the superficial and deep inguinal rings and the inguinal canal in the domestic species.

- Name and identify the structures which pass through the inguinal canal in the male and female domestic animals.

- Explain why pigs are predisposed to inguinal hernias.

- Define cryptorchidism and explain what it means when an animal possesses an inguinal cryptorchid testicle.

- Open the pelvic cavity of carnivore cadavers.

Boundaries of the Pelvic Cavity

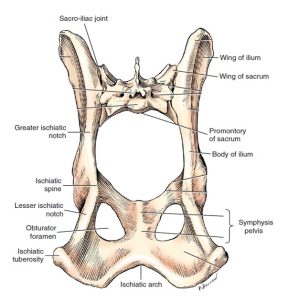

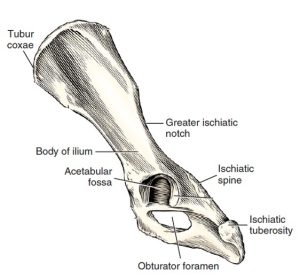

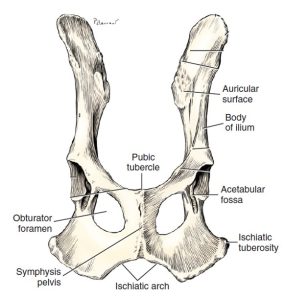

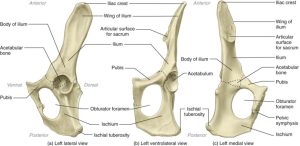

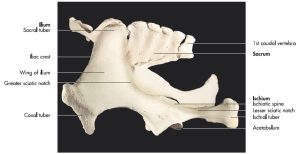

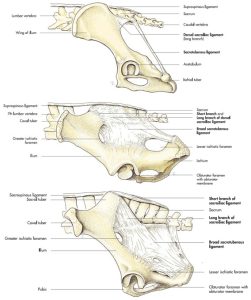

The pelvic girdle, or pelvis, of the dog consists of two hip bones, which are united at the pelvic symphysis ventrally and join the sacrum dorsally. Each hip bone, or os coxae, is formed by the fusion of three primary bones and the addition of a fourth in early life. The largest and most cranial of these is the ilium, which articulates with the sacrum. The ischium is the most caudal, whereas the pubis is located ventromedial to the ilium and cranial to the large obturator foramen. The acetabulum, a socket, is formed where the three bones meet. It receives the head of the femur in the formation of the hip joint (coxofemoral joint). The small acetabular bone, which helps form the acetabulum, is incorporated with the ilium, ischium, and pubis when they fuse (about the third month).

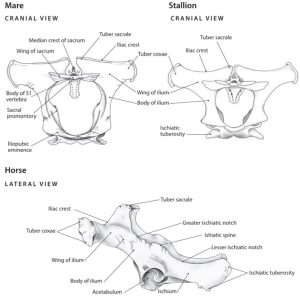

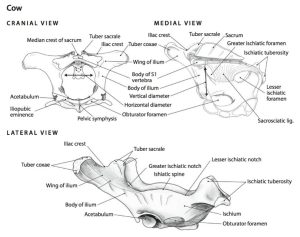

- Pelvis and sacrum, caudodorsal view. 1

- Left os coxae, lateral aspect. 1

- Ventral aspect of ossa coxae. 1

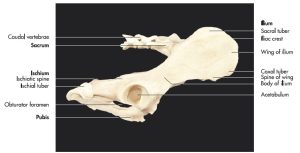

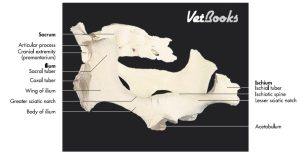

- Cat os coxae 5

- Horse pelvis 6

- Cow pelvis 6

- Hip bones, sacrum and caudal vertebrae of a dog (right lateral aspect). 7

- Hip bones and sacrum of an ox (oblique left lateral aspect). 7

- Hip bones and sacrum of a horse (oblique left lateral aspect). 7

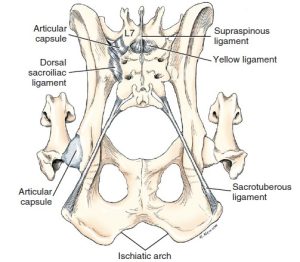

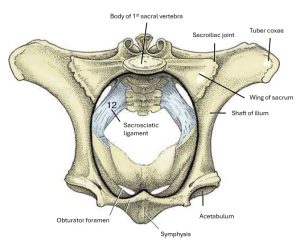

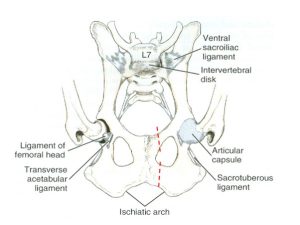

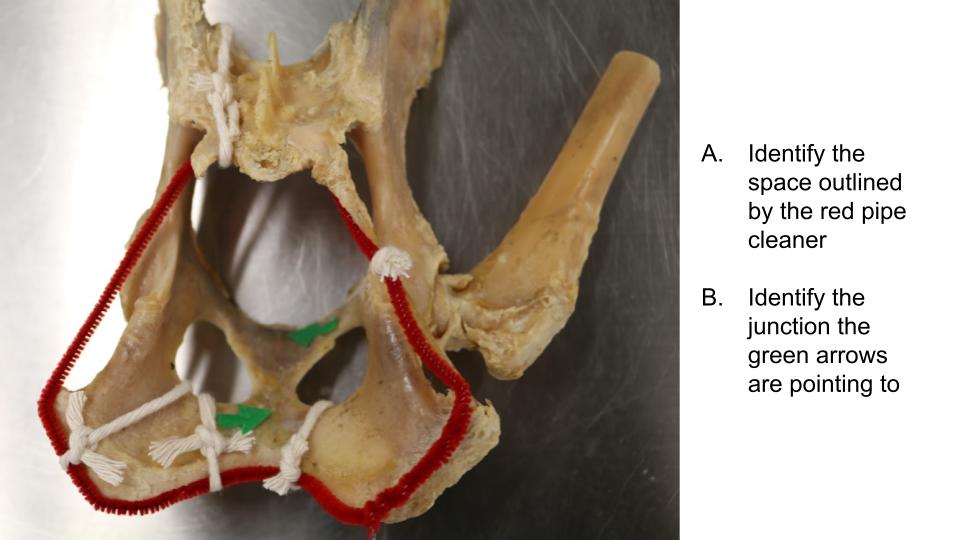

The pelvic canal is short ventrally but long dorsally. Its lateral wall is composed of the ilium, ischium, and pubis. Dorsolateral to the skeletal part of the wall, the pelvic canal is bounded by soft tissues. The pelvic inlet is defined by the cranial aspect of the pelvic girdle. It is bounded laterally and ventrolaterally by the body of the ilium (and even more specifically, the arcuate line). Its dorsal boundary is the promontory and wings of the sacrum. The ventral-most boundary is the brim of the pubis. The pelvic outlet is bounded ventrally by the ischiatic arch (the ischiatic arch is formed by the concave caudal border of the two ischii); mid-dorsally by the first two caudal vertebrae; and laterally by the ischiatic tuberosities and the sacrotuberous ligaments (in the dog; recall that the cat lacks sacrotuberous ligaments). The sacrotuberous ligaments are fibrous bands that runs from the sacrum to the lateral angle of the ischiatic tuberosity (tuber ischii) in the dog.

- Ligaments of pelvis of the dog, dorsal aspect. 1

- Cranial view of the bony pelvis of a cow. The terminal line (black) is indicated. 8

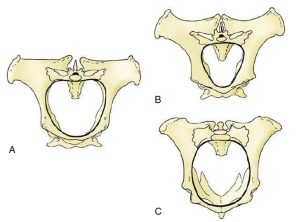

- The differences in the shape of the pelvic inlet of the mare, stallion and cow. 7

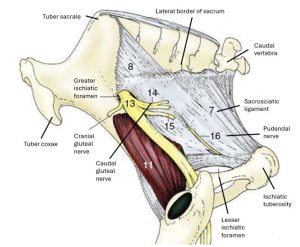

The pelvic cavity is bound by both osseous and soft tissue structures. The soft tissue structures defining the pelvic cavity are the sacrotuberous ligaments in the dog, the sacrosciatic ligaments in the ungulate species, and the pelvic diaphragm mm. – levator ani and coccygeus (will be dissected later). The sacrosciatic ligament also called the broad sacrotuberous ligament, is a broad sheet that extends from the lateral aspect of the sacrum to the dorsal border of the ilium and ischium in the ungulate species. It’s free caudal edge is analogous to the sacrotuberous ligament in the dog. In animals possessing sacrosciatic ligaments, the greater ischiatic (sciatic) foramen is formed by the sacrosciatic ligament bridging the greater ischiatic (sciatic) notch of the ilium. The lesser ischiatic (sciatic) foramen is formed by the sacrosciatic ligament bridging the lesser ischiatic (sciatic) notch of the ischium. The lumbosacral trunk, which gives rise to the sciatic nerve, cranial and caudal gluteal nerves, and the caudal cutaneous femoral nerve, emerges through the greater ischiatic foramen.

FYI – Note in horse: caudal gluteal a/v penetrate through the sacrosciatic lig. dorsally, and no structures pass through lesser ischiatic foramen (except the tendon of the internal obturator m.) The pudendal n. may be seen in the lateral wall of the sacrosciatic lig. in the horse.

- Cranial view of the bony pelvis of a cow. The terminal line (black) is indicated. 8

- Dog sacrotuberous ligament and cow sacrosciatic ligament. 8

- Lateral view of the sacrosciatic ligament of the horse. 8

Between the lateral aspect of the pelvic diaphragm mm. and the medial aspect of the ischiatic tuberosity is a pyramidal-shaped depression, the ischiorectal fossa. The ischiorectal fossa is evident in the ox, goat, sheep, dog and cat, amongst others, because the caudal thigh mm. of these species originate exclusively from the ischiatic tuberosity. The caudal thigh mm. of the horse and pig originate from the sacrum as well as the ischiatic tuberosity, effectively covering the ischiorectal fossa.

- Outline of the ischiorectal fossa, and a normal (taut) sacrosciatic ligament.

- Relaxation of the sacrosciatic ligament (arrow) is an indication of impending parturition. 8

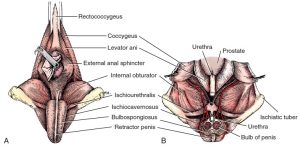

- Male perineum. A, Superficial muscles, caudal aspect. B, Dorsal section through pelvic cavity. The bilobed bulb of the penis is transected, and the proximal portion removed. 1

Observe: Observe full skeletons and pelvic girdles of the domestic species and identify the bones and bony landmarks that define the pelvic cavity. Observe and name the boundaries of the pelvic inlet and outlet. Observe the sacrotuberous ligaments on dog cadavers (if already dissected) and/or plastinated models. Identify the sacrosciatic ligament (broad sacrotuberous ligament) in the horse and ruminants. Identify the greater and lesser ischiatic foramina, and the respective notches of the ilium and ischium.

The Inguinal Canal

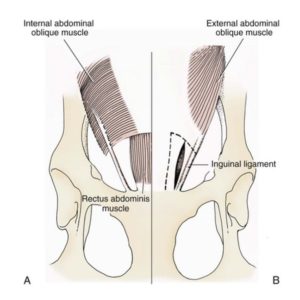

Superficial Inguinal Ring

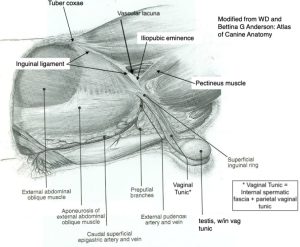

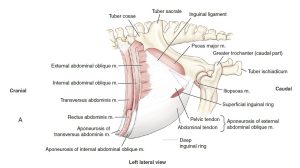

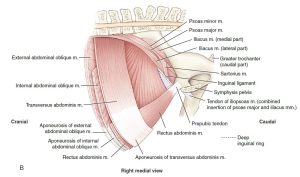

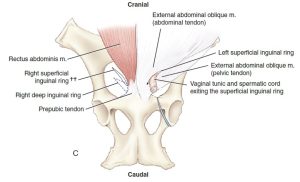

Caudoventrally, just cranial to the iliopubic eminence and lateral to the midline, the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique (EAO) separates into two parts (creating a slit), which then come together again to form the superficial inguinal ring. This is the external opening of a very short natural passageway through the abdominal wall, the inguinal canal. The superficial inguinal ring is a slit in the EAO m. aponeurosis, with a cranial and caudal angle.

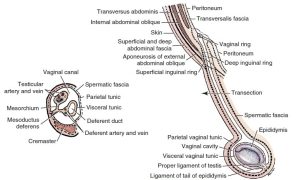

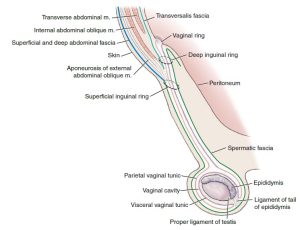

A blind extension of peritoneum protrudes through the inguinal canal to a subcutaneous position outside the body wall. This is the vaginal tunic in the male (a combination of tissue layers which contains the spermatic cord and other structures to be dissected later) and the vaginal process in the bitch (the queen does not have a vaginal process). FYI: Male animals possess a vaginal process from the time that the testicle descends through the inguinal canal until it finally reaches the scrotum. The vaginal tunic/process is covered by the external and internal spermatic fascia, continuations of the subcutaneous tissue of the abdomen and transversalis fascia, respectively. The external and internal spermatic fascia will be further described and identified during the section covering the testicle.

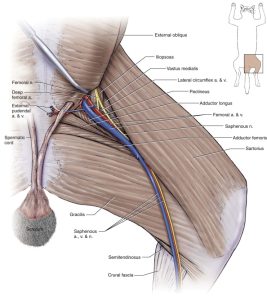

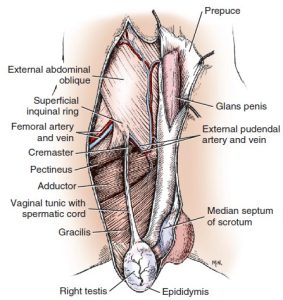

- Abdominal muscles and inguinal region of the male, superficial dissection, left side. 1

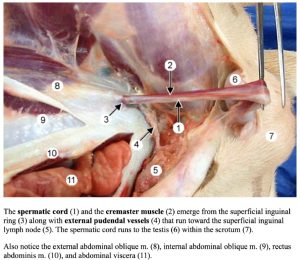

- Inguinal structures of the male dog.

- Diagram of transected vaginal process in male and female. 1

- Dog superficial inguinal ring

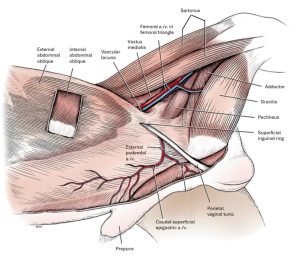

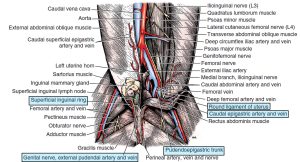

The inguinal ligament is the caudal border of the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique. It terminates on the iliopubic eminence and prepubic tendon (see below for definition). The ventral portion of the ligament is interposed between the superficial inguinal ring and the vascular lacuna. Recall that the vascular lacuna is the base of the femoral triangle, the space that contains the femoral vessels that run to and from the hindlimb. The inguinal ligament thus forms the cranial border of the vascular lacuna and the caudal border of the inguinal canal.

Note: In both sexes of the dog and cat, the external pudendal artery and vein and the genitofemoral nerve also pass through the inguinal canal.

-

Diagrams of the abdominal muscles and inguinal region of

the male, superficial dissection, left side.

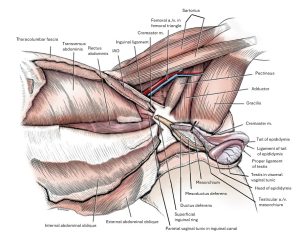

- Abdominal muscles and inguinal region of the male, deep dissection, left side. 1

- Schema of the vaginal tunic in the male with an inset of a transection.1

- Cat medial thigh 5

Dissect: If not completed during the abdominal wall dissection, clear the caudal/inguinal surface of the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique of subcutaneous tissue/external spermatic fascia. Identify the underlying superficial inguinal ring and the spermatic cord. Identify the genitofemoral nerve and external pudendal a/v as they exit the superficial inguinal ring. In the provided figures and on the cadaver, take special note of the distinction between the vascular lacuna (an immediately more prominent structure) versus the superficial inguinal ring.

Observe: On the ungulate species, to identify the superficial inguinal ring, starting at the cranial cut edge of the abdominal wall muscles, pass your hand caudally between the external and internal abdominal oblique mm. towards the inguinal canal. The EAO will be noted to separate into two layers (specifically a pelvic and abdominal crus) forming a slit between them, which is the superficial inguinal ring (as seen from its inner side)!

Deep Inguinal Ring and the Inguinal Canal

The abdominal cavity is lined internally by a double-layer of tissue. Recall that the internal layer is the parietal peritoneum. The oute layer is the transversalis fascia. The transversalis fascia is the thicker, fibrous tissue lining the abdominal cavity whereas the peritoneum is a serous membrane, which under normal circumstances is very thin, transparent and shiny. The deep inguinal rings are covered in parietal peritoneum and transversalis fascia internally, i.e. they are retroperitoneal.

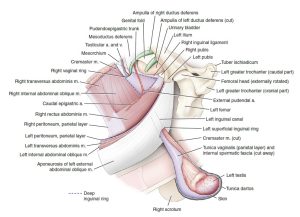

The deep inguinal ring is the internal opening in the abdominal wall, through which the genitofemoral nerve, the external pudendal vessels, lymphatics, and the structures of the spermatic cord (in males), leave/enter the abdominal cavity.

The deep inguinal ring boundaries are:

-

- Cranially – the caudal edge of the internal abdominal oblique m.

- Caudolaterally – the inguinal ligament i.e. the thickened caudal edge of the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique m.

- Medially – the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis m., just cranial to the prepubic tendon. The prepubic tendon is a complex of tendon attachments to the cranial rim of the pubis, and includes the tendon of insertion of the rectus abdominis m.

The inguinal canal is not shaped as a canal per say. The inguinal canal is a short fissure filled with connective tissue between the internal and external abdominal oblique muscles. It extends from the deep to the superficial inguinal ring. As discussed, the superficial inguinal ring is located in the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique and is hardly shaped like a ‘ring’; really it is a slit in the aponeurosis.

- Schematic diagram of inguinal ring anatomy in a dog. A, Deep inguinal ring. B, Superficial inguinal ring. Broken line illustrates close superimposition of the inguinal rings. 1

- Deep and superficial equine inguinal rings, vaginal ring, blood vessels, and associated tissues. 9

-

Sagittal view of the scrotum and the caudal abdomen. The image illustrates the relationship between the abdominal muscles and

testicular sheaths. Cranial is to the left in this image. 9

-

Equine inguinal canal and rings, illustrating the muscles forming the borders of these structures. (A) Lateral view of the left superficial

inguinal ring. The triangular outline of the left deep inguinal ring shows the relative relationship of the superficial and deep rings. The inguinal canal is the fissure-like pathway between the superficial and deep inguinal rings. 9

- Equine inguinal canal and rings, illustrating the muscles forming the borders of these structures. (B) Medial view of the triangular-shaped right deep inguinal ring. 9

-

Ventral view of the abdominal wall and relative locations of the superficial and deep inguinal rings and intervening

inguinal canal. 9

- Borders of the Deep Inguinal Ring

The round ligament of the uterus is a peritoneal fold from the lateral layer of the broad ligament (connecting peritoneum of the ovary, ovarian tube and uterus) – these will be studied in the second part of this unit. The spermatic cord is surrounded in vaginal tunics as it passes through the deep inguinal ring into the inguinal canal. In both sexes the external pudendal vessels and genitofemoral nerve traverse the canal. Unlike in the bitch, the vaginal process is absent in the queen.

The vaginal ring is the opening formed by the parietal peritoneum as it leaves the abdomen, turning sharply to enter the inguinal canal to form the vaginal process or tunic. It marks the position of the deep inguinal ring, but it is a separate structure! A deposit of fat is usually present in the transversalis fascia around the vaginal ring. Note that in the pig, the vaginal ring and deep inguinal ring are relatively large due to the more cranial location of the IAO m. boundary. Thus, the superficial inguinal ring can be seen from the abdominal cavity in the pig. This anatomy also accounts for the predisposition of pigs to inguinal hernias.

The vaginal ring (seen below in a horse cadaver) is NOT the same as the deep inguinal ring. Take care to make the distinction.

- Dissection showing course of the genitofemoral nerve in the female dog, ventral aspect. 1

- Female dog reproductive tract dorsal and lateral views. 9

- Vaginal ring

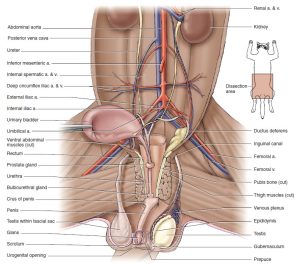

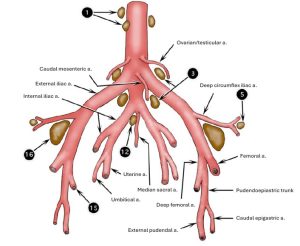

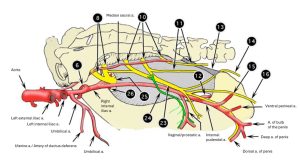

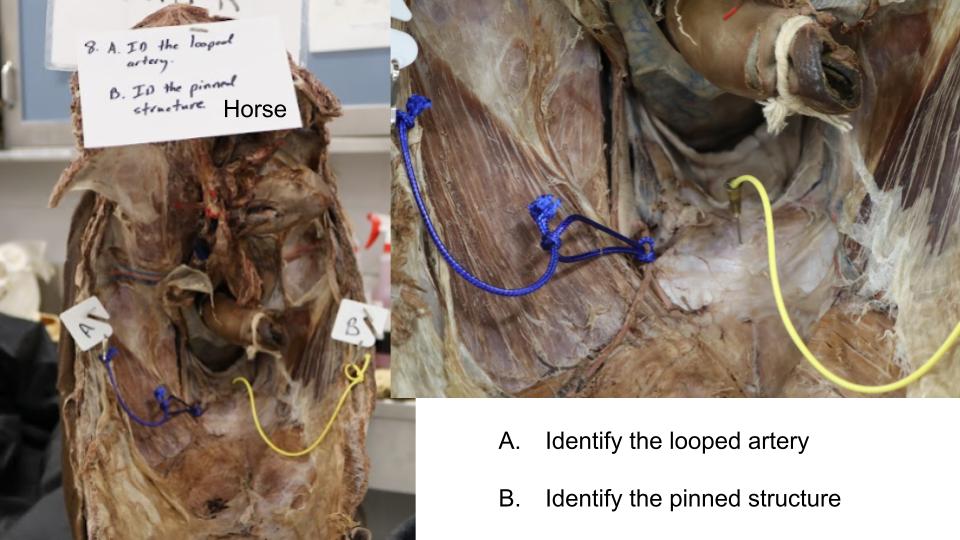

The genitofemoral nerve and external pudendal vessels are retroperitoneal; thus they pass through the inguinal canal and out the superficial inguinal ring adjacent to but external to the internal spermatic fascia (in the male) and external to the vaginal process in the female dog. In other females, the external pudendal aa/vv and genitofemoral nerve pass through the inguinal canal on their own. Recall that the trifurcation, or the termination of the abdominal aorta, includes the right and left external iliac arteries, the left and right internal iliac arteries, and the solitary median sacral artery. Recall from the cardiovascular unit that the external iliac artery gives rise to the deep femoral artery. Once the deep femoral artery branches from the external iliac artery, the latter exits the abdominal cavity via the vascular lacuna and having done so changes name to the femoral artery. It represents the main channel blood supply to the pelvic limb. The deep femoral artery usually gives rise to the pudendoepigastric trunk (PE trunk) in the carnivore and ungulate, from which the caudal epigastric artery branches cranially to run along the internal surface of the rectus abdominus muscle. Also from the PE trunk, the external pudendal artery branches ventrally and exits the abdominal cavity via the inguinal canal. The branching pattern is similar in the cat except that it generally lacks a PE trunk. Instead the caudal epigastric and external pudendal arteries arise separately from the deep femoral artery.

- Male genitalia, ventral view. 1

-

Pelvic cavity of the male cat with urinary bladder

reflected to the right to show vessels and urogenital structures, ventral view. 5

- Termination of bovine aorta with associated lymph nodes, ventral view. 2

- Dissection showing course of the genitofemoral nerve in the female dog, ventral aspect. 1

- Branches of right internal iliac artery of the ox, medial view. 2

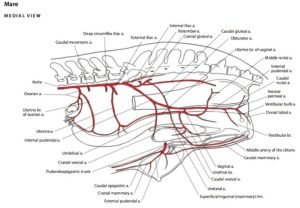

- Arteries of the reproductive tract of the mare. 6

Dissect: First, find the vaginal rings on both sides of the cadaver. Do so by following the spermatic cord to the deep inguinal ring. Clean and identify either the left or right deep inguinal ring by removing the parietal peritoneum and transversalis fascia covering it, and hence the vaginal ring, leaving the other side intact.

Observe:

In the carnivore, locate the caudal epigastric artery running along the rectus abdominus muscle. Recall that the caudal epigastric artery is a branch of the pudendoepigastric trunk in the dog, along with the external pudendal artery. The cat usually lacks a PE trunk and therefore the caudal epigastric and external pudendal arteries are direct branches from the deep femoral artery. These arteries were dissected when the pelvic limb arteries were studied, because they are more accessible from that perspective, but keep in mind that these vessels actually branch within the abdominal cavity. Make an attempt to locate them now, but don’t worry about it if the anatomy is too corrupted. You’ll be able to visualize them readily in the ungulate.

In the ungulate, locate the caudal epigastric artery running along the rectus abdominus muscle. Follow it back to the pudendoepigastric trunk. The external pudendal artery should be readily visualized at this point entering the deep inguinal ring next to the genitofemoral nerve. Now, follow the PE trunk back to the deep femoral artery and ultimately to the external iliac artery.

Trace the genitofemoral nerve and external pudendal artery into the deep inguinal ring and note them again external to the superficial inguinal ring. Again note the boundaries of the deep inguinal ring, and list the structures which pass through it in the male and female animal.

Clinical Application: Inguinal hernias in the pig

In young, male pigs, the large deep inguinal ring and vaginal ring is thought to be an anatomical reason for the relatively high occurrence of inguinal hernias, in which a loop of intestine descends into the vaginal cavity.

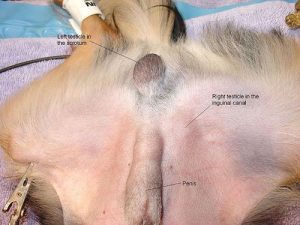

Clinical Application: Inguinal Cryptorchid testicles

Testicles develop embryologically in the abdomen and then descend into the scrotum. Failure to descend all the way into the scrotum is called cryptorchidism. The testicle may remain entirely in the abdominal cavity, become stuck in the inguinal canal (called a high flanker in horses) or stop just external to the superficial inguinal ring, in the subcutaneous tissue of the inguinal region, where it must be differentiated from the superficial inguinal lymph node. Castration and cryptorchid surgeries, particularly in the stallion, require an excellent understanding of inguinal canal and vaginal tunic and spermatic cord anatomy. The retained testicle is often in the inguinal canal or located abdominally and palpation of the superficial inguinal ring (when the horse is anesthetized and in dorsal recumbency) provides the landmark for the skin incision for the inguinal approach to finding the testicle.

- Dog with inguinal testicle. VetHQ

- Cryptorchid horse. Green ovals provide the landmark for the skin incision for the inguinal approach to finding the testicle. RVETS.org

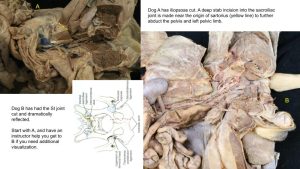

Dissect: Opening the Pelvic Cavity

To cut open the pelvis, we must first remove some musculature. On the left pelvic limb, transect the adductor m. and pectineus m. away from the pelvic symphysis and iliopubic eminence, respectively. You may wish to remove a section of the belly of the adductor for optimum viewing. Next, cut through the external obturator m. near midline and reflect it toward the limb – this helps define the margins of the obturator foramen using firm palpation. Note, the external obturator is often partly cut when the adductor is transected, because it lies directly deep to the adductor. Use a scalpel to cut through any remaining soft tissues on the ventral ischium and pubis at the sites shown on the image below, ie to the left of the midline pelvic symphysis and extending into the obturator foramen (which is filled with internal obturator m.). Create a tissue tunnel with a scissor or hemostat dorsal to the ischium and pubis at the cut locations so it is easier to insert the cutting tool. Then position the bone cutters, slightly off midline at the designated sites, and cut through the pubis and ischium.

We now need to release tension on the internal vasculature by transecting the femoral artery and vein. Do this approximately two inches down the limb so you will be able to identify the stump of the femoral artery later.

With the ventral pelvic bones cut, we will now spread the pelvis open by transecting the ventral aspect of the sacroiliac joint. To visualize this joint, begin by palpating deeply between the body wall and craniomedial aspect of the pelvic limb (typically near sartorius). The round muscle you will be feeling will be iliopsoas and psoas minor – transect these muscles transversely. Start to apply abduction pressure to the limb and at this point, you should be able to palpate the ventral aspect of the sacroiliac joint by passing a finger down the medial side of the ilium. Use a scalpel to cut down into this joint.

Take advantage of leverage by placing your dog (unnecessary for cats) on the edge of the table with the left limb splayed over the side. Apply even and constant lateral and downward pressure to the ventral pelvis at the level of the cuts you made in the left os coxae to open the pelvic cavity. Avoid applying excessive pressure by abducting the limb at its hip joint because this may luxate the femoral head from the acetabulum. If this does occur, however, simply refocus your force on the pelvis alone and apply pressure again. If you have successfully cut through the SI joint, you will hear it crack and break under pressure.

This will open the pelvic cavity. If necessary, remove more of the pubis and ischium on the cut surfaces to further expose the pelvic cavity. Reflect the external genitalia to the right and, for males, cut the attachment of the penis to the left ischiatic tuberosity. Leave the limb attached. All structures more easily traced from the left should be dissected from this side. To expose the pelvic wall muscles, we may need to transect the internal obturator m. from its midline attachments. This will expose the thin levator ani m. underneath. Eventually, we will sacrifice the left body wall and inguinal canal region to follow structures from the abdomen into the pelvic cavity.

Opening the pelvic cavity – 4 min

Review videos

Pelvis osteology – 4 min

Inguinal rings (dog) – 3 min, watch until 24:30

Deep inguinal ring (horse) – watch until 7 min

Inguinal rings model – 7 min

Terms

| Boundaries of the Pelvic Cavity | ||

| Osteology | Features | Species differences/comments |

| Pelvic girdle/pelvis | ||

| Pelvic symphysis | ||

| Os coxae | ||

| Ilium | Wing of the Ilium | |

| Tuber coxae | ||

| Body of the Ilium | ||

| Ischium | Ischiatic tuberosity | |

| Ischiatic arch | ||

| Obturator foramen | ||

| Greater ischiatic notch | ||

| Lesser ischiatic notch | ||

| Pubis | Body of the Pubis | |

| Sacrum | Wings of the sacrum | |

| Promontory | ||

| Pelvic girdle (pelvis) | Pelvic inlet (and define boundaries) | |

| Pelvic outlet (and define boundaries) | ||

| Pelvic symphysis | ||

| Sacroiliac joint | ||

| Sacrotuberous ligament | Dog only | |

| Sacrosciatic ligament | aka broad sacrotuberous ligament | Ungulates |

| Greater ischiatic (sciatic) foramen | ||

| Lesser ischiatic (sciatic) foramen | ||

| Sciatic nerve | ||

| Pelvic canal | ||

| Pelvic inlet | ||

| Pelvic outlet | ||

| Pelvic diaphragm mm. | Levator ani and coccygeus mm. | Will be identified later this unit |

| Ischiorectal fossa | Depression between lateral aspect of pelvic diaphragm mm. and medial aspect of ischiatic tuberosity | |

| Inguinal Canal and Peritoneum | ||

| Term | Features | Species differences/comments |

| Inguinal canal | Short fissure between superficial inguinal ring and deep inguinal ring | |

| Superficial inguinal ring | Slit in external abdominal oblique (EAO) | |

| Deep inguinal ring | Caudal edge of Internal abdominal oblique m. | Cranial boundary |

| Inguinal ligament (caudal edge of EAO) | Caudolateral boundary | |

| Lateral edge of the rectus abdominus muscle | Medial boundary | |

| Parietal peritoneum | Internal lining of abdominal cavity (very thin and shiny) | |

| Transversalis fascia | External lining of abdominal cavity (thicker white, fibrous layer) | |

| Vaginal tunic | Combination of tissue layers which contains the spermatic cord | |

| The Terminal Aorta and its Branches | |

| Term | Features |

| External iliac arteries | Deep femoral artery |

| Pudendoepigastric trunk (PE trunk) | |

| Caudal epigastric artery | |

| External pudendal artery | |

| Femoral artery | |

| Vascular lacuna | Space that contains the femoral vessels |

| Internal iliac arteries | |

| Median sacral artery | |

| Genitofemoral nerve | |