Lab 6A, 8A, 9A: Inguinal Canal and Comparative Female Genitalia 1

Learning Objectives

- Review the pelvic canal and its boundaries. Define dystocia and differentiate between characteristics of the pelvic canal in the domestic species. Relate these differences to prevalence of dystocia in the cow and carnivore. Define a “downer cow,” and describe ways to treat this condition.

- Review inguinal canal anatomy in the female domestic species.

- Define the pelvic cavity pouches surrounding the pelvic viscera and specifically understand the anatomical importance of foaling injuries in the mare in relation to the peritoneal reflections in the pelvic cavity.

- Review the anatomy of the urinary bladder urethra and apply this knowledge to these structures in the female domestic species.

- Identify the major features of the female reproductive tract in the domestic species.

- Relate the genital anatomy of the female domestic species to clinical conditions.

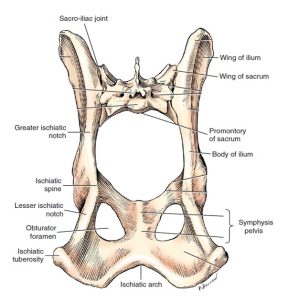

Boundaries of the Pelvic Cavity

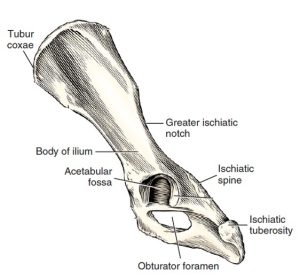

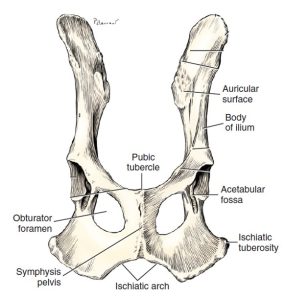

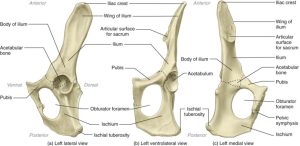

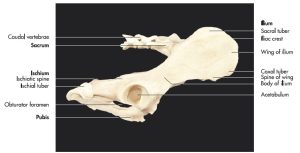

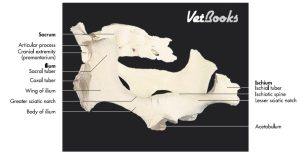

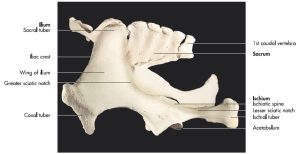

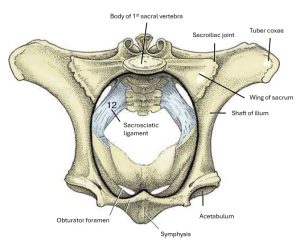

The pelvic girdle, or pelvis, of the dog consists of two hip bones, which are united at the pelvic symphysis ventrally and join the sacrum dorsally. Each hip bone, or os coxae, is formed by the fusion of three primary bones and the addition of a fourth in early life. The largest and most cranial of these is the ilium, which articulates with the sacrum. The ischium is the most caudal, whereas the pubis is located ventromedial to the ilium and cranial to the large obturator foramen. The acetabulum, a socket, is formed where the three bones meet. It receives the head of the femur in the formation of the hip joint (coxofemoral joint). The small acetabular bone, which helps form the acetabulum, is incorporated with the ilium, ischium, and pubis when they fuse (about the third month).

- Pelvis and sacrum, caudodorsal view. 1

- Left os coxae, lateral aspect. 1

- Ventral aspect of ossa coxae. 1

- Cat os coxae 5

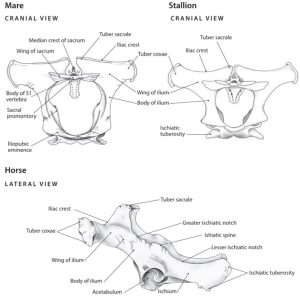

- Horse pelvis 6

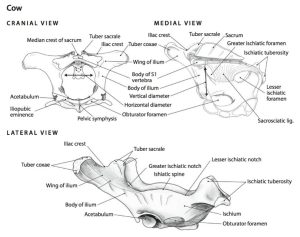

- Cow pelvis 6

- Hip bones, sacrum and caudal vertebrae of a dog (right lateral aspect). 7

- Hip bones and sacrum of an ox (oblique left lateral aspect). 7

- Hip bones and sacrum of a horse (oblique left lateral aspect). 7

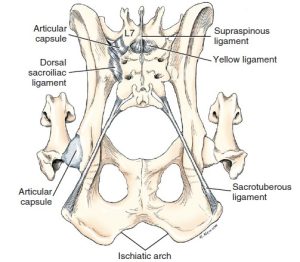

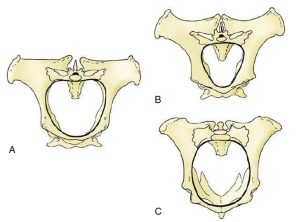

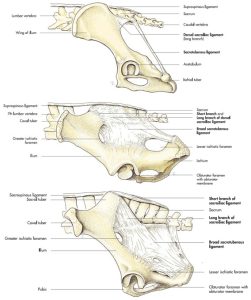

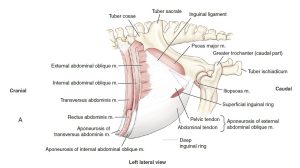

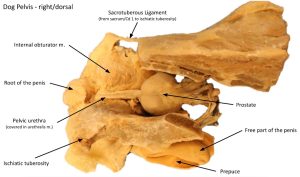

The pelvic canal is short ventrally but long dorsally. Its lateral wall is composed of the ilium, ischium, and pubis. Dorsolateral to the skeletal part of the wall, the pelvic canal is bounded by soft tissues. The pelvic inlet is defined by the cranial aspect of the pelvic girdle. It is bounded laterally and ventrolaterally by the body of the ilium (and even more specifically, the arcuate line). Its dorsal boundary is the promontory and wings of the sacrum. The ventral-most boundary is the brim of the pubis. The pelvic outlet is bounded ventrally by the ischiatic arch (the ischiatic arch is formed by the concave caudal border of the two ischii); mid-dorsally by the first two caudal vertebrae; and laterally by the ischiatic tuberosities and the sacrotuberous ligaments (in the dog; recall that the cat lacks sacrotuberous ligaments). The sacrotuberous ligaments are fibrous bands that runs from the sacrum to the lateral angle of the ischiatic tuberosity (tuber ischii) in the dog.

- Ligaments of pelvis of the dog, dorsal aspect. 1

- Cranial view of the bony pelvis of a cow. The terminal line (black) is indicated. 8

- The differences in the shape of the pelvic inlet of the mare, stallion and cow. 7

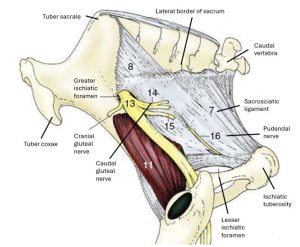

The pelvic cavity is bound by both osseous and soft tissue structures. The soft tissue structures defining the pelvic cavity are the sacrotuberous ligaments in the dog, the sacrosciatic ligaments in the ungulate species, and the pelvic diaphragm mm. – levator ani and coccygeus (will be dissected later). The sacrosciatic ligament also called the broad sacrotuberous ligament, is a broad sheet that extends from the lateral aspect of the sacrum to the dorsal border of the ilium and ischium in the ungulate species. It’s free caudal edge is analogous to the sacrotuberous ligament in the dog. In animals possessing sacrosciatic ligaments, the greater ischiatic (sciatic) foramen is formed by the sacrosciatic ligament bridging the greater ischiatic (sciatic) notch of the ilium. The lesser ischiatic (sciatic) foramen is formed by the sacrosciatic ligament bridging the lesser ischiatic (sciatic) notch of the ischium. The lumbosacral trunk, which gives rise to the sciatic nerve, cranial and caudal gluteal nerves, and the caudal cutaneous femoral nerve, emerges through the greater ischiatic foramen.

FYI – Note in horse: caudal gluteal a/v penetrate through the sacrosciatic lig. dorsally, and no structures pass through lesser ischiatic foramen (except the tendon of the internal obturator m.) The pudendal n. may be seen in the lateral wall of the sacrosciatic lig. in the horse.

- Cranial view of the bony pelvis of a cow. The terminal line (black) is indicated. 8

- Dog sacrotuberous ligament and cow sacrosciatic ligament. 8

- Lateral view of the sacrosciatic ligament of the horse. 8

Between the lateral aspect of the pelvic diaphragm mm. and the medial aspect of the ischiatic tuberosity is a pyramidal-shaped depression, the ischiorectal fossa. The ischiorectal fossa is evident in the ox, goat, sheep, dog and cat, amongst others, because the caudal thigh mm. of these species originate exclusively from the ischiatic tuberosity. The caudal thigh mm. of the horse and pig originate from the sacrum as well as the ischiatic tuberosity, effectively covering the ischiorectal fossa.

- Outline of the ischiorectal fossa, and a normal (taut) sacrosciatic ligament.

- Relaxation of the sacrosciatic ligament (arrow) is an indication of impending parturition. 8

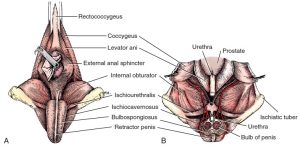

- Male perineum. A, Superficial muscles, caudal aspect. B, Dorsal section through pelvic cavity. The bilobed bulb of the penis is transected, and the proximal portion removed. 1

Observe: Observe full skeletons and pelvic girdles of the domestic species and identify the bones and bony landmarks that define the pelvic cavity. Observe and name the boundaries of the pelvic inlet and outlet. Observe the sacrotuberous ligaments on dog cadavers (if already dissected) and/or plastinated models. Identify the sacrosciatic ligament (broad sacrotuberous ligament) in the horse and ruminants. Identify the greater and lesser ischiatic foramina, and the respective notches of the ilium and ischium.

Clinical Application: Dystocia in the Cow

Dystocia: The term dystocia refers to difficult birth, typically caused by a too large and/or awkwardly positioned fetus, by smallness of the maternal pelvis, or by failure of the uterus and cervix to contract and expand normally.

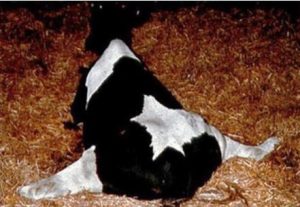

Dystocia in the cow is associated with the cow’s small pelvic outlet and steep slope of the pelvic floor. Pressure from the calf in the pelvic canal can damage the obturator n. where it courses along the medial aspect of the shaft of the ilium. Subsequent paralysis of the obturator n. prevents adduction of the pelvic limbs and the cow is unable to stand. This clinical condition can be one cause of the “downer cow syndrome.” In the case of a down cow, the sciatic nerve can also be damaged and present as sciatic, and/or tibial, and/or common fibular (peroneal) nerve dysfunction. Common fibular n. dysfunction may be the most common due to the superficial nature of the nerve. It may get compressed while the cow is lying on her side delivering the calf.

- Downer cow with splayed (abducted) limbs.

- Cow being lifted

- Cow being floated

Thanks to the buoyancy of the gas in the rumen, cows can be floated in water to help them stand and recover. See a cow being floated here.

Clinical Application: Dystocia in the Carnivore

Note that in the carnivore, the pelvic inlet has a smaller circumference than does the pelvic outlet. Therefore, the most common place for a fetus to be stuck in the pelvic canal due to maternal/fetal size mismatch or a malpresented fetus is at the pelvic inlet. In these cases, a Cesearean section is necessary to remove the fetus. A Cesarean section, or C-section, is a surgical procedure by which a fetus is delivered through incisions made in the mother’s abdomen and uterus.

- Exteriorized pregnant dog uterus.

Read More: Cesarean Section in the Dog

The Inguinal Canal

Superficial Inguinal Ring

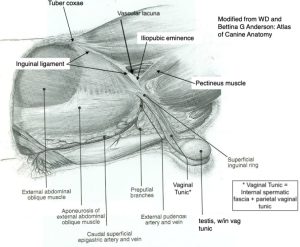

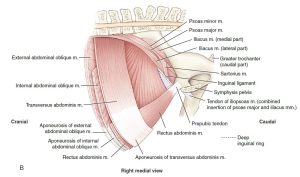

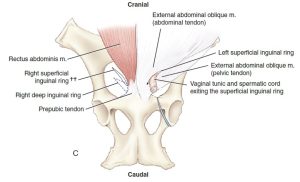

Caudoventrally, just cranial to the iliopubic eminence and lateral to the midline, the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique (EAO) separates into two parts (creating a slit), which then come together again to form the superficial inguinal ring. This is the external opening of a very short natural passageway through the abdominal wall, the inguinal canal. The superficial inguinal ring is a slit in the EAO m. aponeurosis, with a cranial and caudal angle.

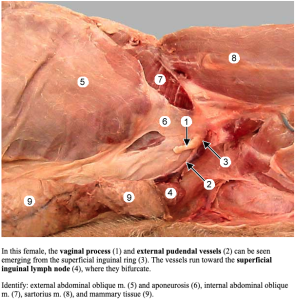

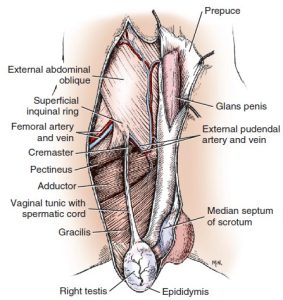

A blind extension of peritoneum protrudes through the inguinal canal to a subcutaneous position outside the body wall. This is the vaginal tunic in the male (a combination of tissue layers which contains the spermatic cord and other structures to be dissected later) and the vaginal process in the bitch (the queen does not have a vaginal process). FYI: Male animals possess a vaginal process from the time that the testicle descends through the inguinal canal until it finally reaches the scrotum. The vaginal process is covered by the external and internal spermatic fascia, continuations of the subcutaneous tissue of the abdomen and transversalis fascia, respectively.

- Abdominal muscles and inguinal region of the male, superficial dissection, left side. 1

- Diagram of transected vaginal process in male and female. 1

- Vaginal process and related structures in the female dog.

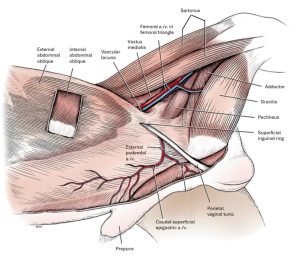

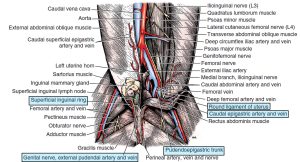

The inguinal ligament is the caudal border of the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique. It terminates on the iliopubic eminence and prepubic tendon (see below for definition). The ventral portion of the ligament is interposed between the superficial inguinal ring and the vascular lacuna. Recall that the vascular lacuna is the base of the femoral triangle, the space that contains the femoral vessels that run to and from the hindlimb. The inguinal ligament thus forms the cranial border of the vascular lacuna and the caudal border of the inguinal canal.

Note: In both sexes of the dog and cat, the external pudendal artery and vein and the genitofemoral nerve also pass through the inguinal canal.

-

Diagrams of the abdominal muscles and inguinal region of

the male, superficial dissection, left side.

Dissect: If not completed during the abdominal wall dissection, clear the caudal/inguinal surface of the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique of subcutaneous tissue/external spermatic fascia. Identify the underlying superficial inguinal ring. Identify the genitofemoral nerve and external pudendal a/v as they exit the superficial inguinal ring. In the provided figures and on the cadaver, take special note of the distinction between the vascular lacuna (an immediately more prominent structure) versus the superficial inguinal ring.

Observe: On the ungulate species, identify the superficial inguinal ring, starting at the cranial cut edge of the abdominal wall muscles, pass your hand caudally between the external and internal abdominal oblique mm. towards the inguinal canal. The EAO will be noted to separate into two layers (specifically a pelvic and abdominal crus) forming a slit between them, which is the superficial inguinal ring (as seen from its inner side)!

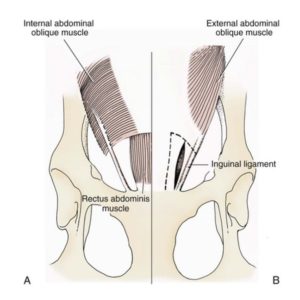

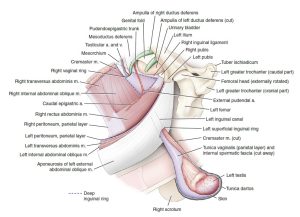

Deep Inguinal Ring and the Inguinal Canal

The abdominal cavity is lined internally by a double-layer of tissue. Recall that the internal layer is the parietal peritoneum. The oute layer is the transversalis fascia. The transversalis fascia is the thicker, fibrous tissue lining the abdominal cavity whereas the peritoneum is a serous membrane, which under normal circumstances is very thin, transparent and shiny. The deep inguinal rings are covered in parietal peritoneum and transversalis fascia internally, i.e. they are retroperitoneal.

The deep inguinal ring is the internal opening in the abdominal wall, through which the genitofemoral nerve, the external pudendal vessels, lymphatics, and the structures of the spermatic cord (in males), leave/enter the abdominal cavity.

The deep inguinal ring boundaries are:

-

- Cranially – the caudal edge of the internal abdominal oblique m.

- Caudolaterally – the inguinal ligament i.e. the thickened caudal edge of the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique m.

- Medially – the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis m., just cranial to the prepubic tendon. The prepubic tendon is a complex of tendon attachments to the cranial rim of the pubis, and includes the tendon of insertion of the rectus abdominis m.

The inguinal canal is not shaped as a canal per say. The inguinal canal is a short fissure filled with connective tissue between the internal and external abdominal oblique muscles. It extends from the deep to the superficial inguinal ring. As discussed, the superficial inguinal ring is located in the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique and is hardly shaped like a ‘ring’; really it is a slit in the aponeurosis.

- Schematic diagram of inguinal ring anatomy in a dog. A, Deep inguinal ring. B, Superficial inguinal ring. Broken line illustrates close superimposition of the inguinal rings. 1

- Deep and superficial equine inguinal rings, vaginal ring, blood vessels, and associated tissues. 9

-

Equine inguinal canal and rings, illustrating the muscles forming the borders of these structures. (A) Lateral view of the left superficial

inguinal ring. The triangular outline of the left deep inguinal ring shows the relative relationship of the superficial and deep rings. The inguinal canal is the fissure-like pathway between the superficial and deep inguinal rings. 9

- Equine inguinal canal and rings, illustrating the muscles forming the borders of these structures. (B) Medial view of the triangular-shaped right deep inguinal ring. 9

-

Ventral view of the abdominal wall and relative locations of the superficial and deep inguinal rings and intervening

inguinal canal. 9

- Borders of the Deep Inguinal Ring

In the female domestic species, the round ligament of the uterus is a peritoneal fold from the lateral layer of the broad ligament (connecting peritoneum of the ovary, ovarian tube and uterus). In both sexes the external pudendal vessels and genitofemoral nerve traverse the canal.

The vaginal ring is the opening formed by the parietal peritoneum as it leaves the abdomen, turning sharply to enter the inguinal canal to form the vaginal process or tunic. It marks the position of the deep inguinal ring, but it is a separate structure! A deposit of fat is usually present in the transversalis fascia around the vaginal ring. Note that in the pig, the vaginal ring and deep inguinal ring are relatively large due to the more cranial location of the IAO m. boundary. Thus, the superficial inguinal ring can be seen from the abdominal cavity in the pig. This anatomy also accounts for the predisposition of pigs to inguinal hernias.

The vaginal ring (seen below in a horse cadaver) is NOT the same as the deep inguinal ring. Take care to make the distinction.

- Dissection showing course of the genitofemoral nerve in the female dog, ventral aspect. 1

- Female dog reproductive tract dorsal and lateral views. 9

- Vaginal ring

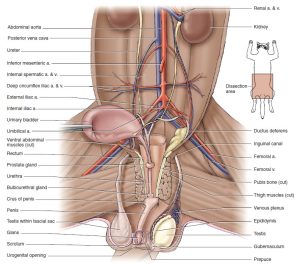

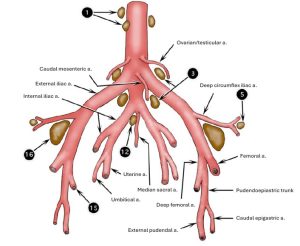

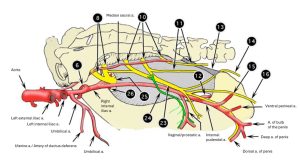

The genitofemoral nerve and external pudendal vessels are retroperitoneal; thus they pass through the inguinal canal and out the superficial inguinal ring adjacent to but external to the internal spermatic fascia (in the male) and external to the vaginal process in the female dog. In other females, the external pudendal aa/vv and genitofemoral nerve pass through the inguinal canal on their own. Recall that the trifurcation, or the termination of the abdominal aorta, includes the right and left external iliac arteries, the left and right internal iliac arteries, and the solitary median sacral artery. Recall from the cardiovascular unit that the external iliac artery gives rise to the deep femoral artery. Once the deep femoral artery branches from the external iliac artery, the latter exits the abdominal cavity via the vascular lacuna and having done so changes name to the femoral artery. It represents the main channel blood supply to the pelvic limb. The deep femoral artery usually gives rise to the pudendoepigastric trunk (PE trunk) in the carnivore and ungulate, from which the caudal epigastric artery branches cranially to run along the internal surface of the rectus abdominus muscle. Also from the PE trunk, the external pudendal artery branches ventrally and exits the abdominal cavity via the inguinal canal. The branching pattern is similar in the cat except that it generally lacks a PE trunk. Instead the caudal epigastric and external pudendal arteries arise separately from the deep femoral artery.

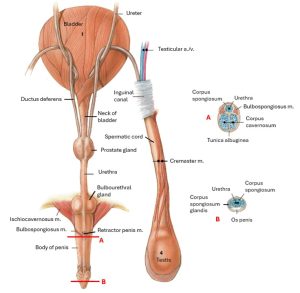

- Male genitalia, ventral view. 1

-

Pelvic cavity of the male cat with urinary bladder

reflected to the right to show vessels and urogenital structures, ventral view. 5

- Termination of bovine aorta with associated lymph nodes, ventral view. 2

- Dissection showing course of the genitofemoral nerve in the female dog, ventral aspect. 1

- Branches of right internal iliac artery of the ox, medial view. 2

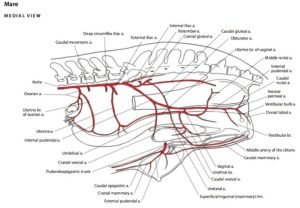

- Arteries of the reproductive tract of the mare. 6

Dissect: In the female carnivore cadavers, find the round ligament of the uterus running toward the inguinal canal. Observe the vaginal ring. Review the arteries described above on the limb dissected for the cardiovasuclar unit. Find the superficial inguinal ring and review the external pudendal artery and genitofemoral nerve exiting the inguinal canal. In the bitch, observe the vaginal process.

The Urinary Bladder and Pelvic Urethra

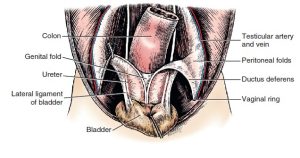

The urinary bladder is a muscular, expandable sac in the lower abdomen that serves as a temporary storage space for urine produced by the kidneys. The urinary bladder has an apex, a body, and a neck. Three connecting peritoneal folds (ligaments) are reflected from the bladder on the pelvic and abdominal walls. The median ligament of the bladder leaves the ventral surface of the bladder and attaches to the abdominal wall as far cranial as the umbilicus. In the fetus it contains the urachus and umbilical arteries. These degenerate and leave no ligamentous remnant in the adult. The lateral ligaments of the bladder pass from the left and right sides of the bladder to the pelvic wall and often contain an accumulation of fat along with the ureter and umbilical arteries (in the fetus, or if still patent in the adult). The round ligaments of the bladder, along the cranial free edges of the lateral ligaments of the bladder, are the adult remnants of the fetal umbilical arteries once they are no longer patent. All of the structures of fetal circulation will be covered in the lab over placentas.

-

Urogenital ligaments of the male, ventral

aspect. 1

- Female goat pelvic viscera at pelvic inlet. 22

- Pelvic peritoneal pouches in a female (above) and male (below) animal. 7

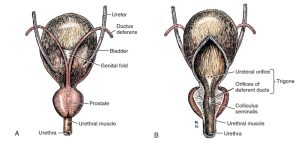

Bundles of smooth muscle on the surface of the bladder pass obliquely across the neck of the bladder and the origin of the urethra. These bundles, collectively called the detrusor m., are innervated by the pelvic nerve (sacral parasympathetic neurons).

Recall that the ureters lie opposite each other near the neck of the urinary bladder. The trigone of the bladder is the dorsal triangular area located within the line drawn between the two ureteral openings and the lines connecting each ureteral opening with the urethral exit from the bladder.

No gross anatomical sphincter is present in the neck of the bladder, but a physiological sphincter of smooth muscle is innervated by the hypogastric nerves, which supply sympathetic visceral efferent innervation. This smooth muscle is called the internal urethral sphincter and is continuous with the detrusor muscle. It’s responsible for the involuntary control of urine flow from the bladder through the internal urethral orifice, which is the opening between the urinary bladder and pelvic urethra.

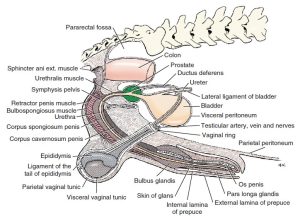

Recall that the male urethra is composed of a pelvic part (pelvic urethra) within the pelvis and a penile part within the penis (penile urethra). Females, lacking both a penis and prostate gland, possess only a pelvic urethra.

- Bladder and prostate. A, Dorsal aspect. B, Ventral aspect, partially opened on midline. 1

- Diagram of peritoneal reflections and the male genitalia. 1

- Male genital system of the cat with some muscles and prepuce removed, dorsal view. 4

- Male dog pelvic wall mm.

- Prostate gland of the dog

- Lateral contrast radiograph of the bladder and urethra in the male dog.

The urethral muscle (urethralis m) is striated and is confined to the pelvis, where it surrounds (in the male) the pelvic urethra and serves as a voluntary sphincter to retain the urine. In the female, the urethralis m. originates from the sides of the vagina and forms a sling ventral to the urethra and also serves as a voluntary sphincter. The pelvic urethra is continuous with the penile urethra in the male, which begins caudally at the level of the ischiatic crest, where the root of the penis is located. It DOES NOT extend around the penile urethra in the male. The urethralis muscle may also be called the external urethral sphincter. The urethralis m./external urethral sphincter is innervated by the pudendal nerve (sacral somatic efferent neurons).

Urine exits the urethra through the external urethral orifice. Remember that in the male, the external urethral orifice is located at the distal end of the penile urethra. The female animal, quite obviously, does not possess a penile urethra. In the female domestic species, the pelvic urethra empties into the vestibule through the external urethral orifice, which will be studied in relation to the female genitalia later in this unit.

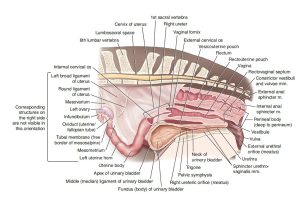

- Female pelvic viscera, median section, left lateral view. 1

Observe the pattern of the bundles of smooth muscle on the surface of the bladder (detrusor m). Identify the prostate gland in the male cadavers, a relatively large gland located just caudal to the neck of the bladder. Identify the pelvic urethra surrounded by (males), or supported by (females), the urethralis m.

Dissect: Make a ventral incision in the bladder wall (a cystotomy!) just to the left side of the medial ligament of the bladder, so as to keep the ligament intact. Extend the incision caudally towards the neck of the bladder, reaching the start of the urethra. In males, where possible, extend this incision through the prostatic urethra (a subpart of the pelvic urethra which runs through the prostate gland) and into the pelvic urethra. Come back to this last step later in the dissection if need be. Examine the mucosae of the bladder and urethra. If needed to better visualize these structures, you may transect the remaining abdominal wall. In doing so, avoid disrupting the superficial inguinal ring.

If the bladder is contracted, its mucosa will be thrown into numerous folds, or rugae, as a result of its inelasticity.

Observe the entrance of the ureters into the bladder and point to where the internal urethral sphincter (not a gross structure) is located – at the neck of the bladder, cranial to the prostate in the male and in an analogous position in the female. Identify the trigone of the bladder.

Observe: Review wet specimens with opened urinary bladder and incised pelvic urethra to study the urinary bladder and pelvic urethral anatomy of the ungulate species. Come back to this anatomy as you review the internal and external genitalia of the ungulate species.

Female Reproductive Tracts

Observe: Use wet prosections of female reproductive tracts and female cadavers to identify the structures in this section.

Carnivores

Ovaries and associated structures

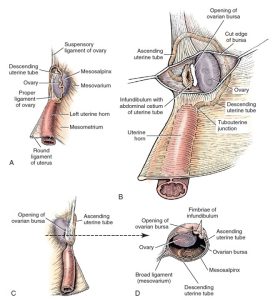

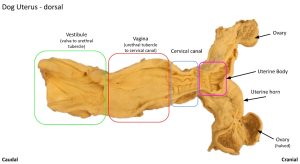

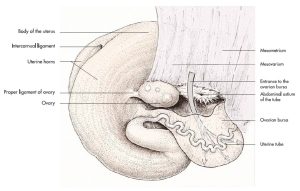

The ovaries are located near the caudal pole of the kidneys. The right ovary lies cranial to the left ovary and is dorsal to the descending duodenum. The left ovary is between the descending colon and the abdominal wall. Each ovary is enclosed in a thin-walled peritoneal sac, the ovarian bursa, formed by the mesovarium and mesosalpinx. The ovarian bursa is open to the peritoneal cavity by means of a slit-like orifice on the medial surface.

The uterine tube courses cranially and then caudally through the lateral wall of the bursa on its way to the uterine horn.

The infundibulum is the dilated ovarian end of the uterine tube. It has a fimbriated margin and functions to engulf the oocyte after ovulation. Note that several of the fimbriae protrude into the peritoneal cavity from the opening of the ovarian bursa. In life, these fimbriae function to close the opening into the peritoneal cavity at the time of ovulation and thus prevent transperitoneal migration of oocytes. The entrance of the infundibulum into the uterine tube is often described as the abdominal ostium, and it is in this region that fertilization takes place. The uterine tube is short and slender. It opens into the much wider uterine horn at the tubouterine junction. This region is of physiological importance because it is here that sperm and ova are regulated in their transit.

-

Relations of left ovary and ovarian bursa. A, Lateral aspect. B, Lateral aspect, ovarian bursa opened.

C, Medial aspect. D, Section through ovary and ovarian bursa. 1

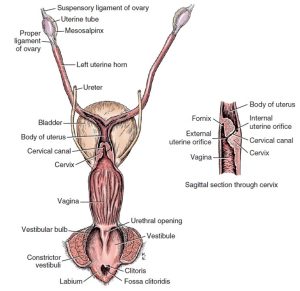

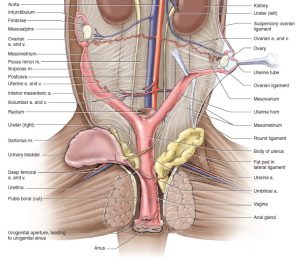

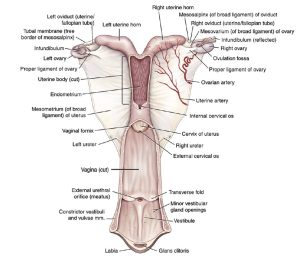

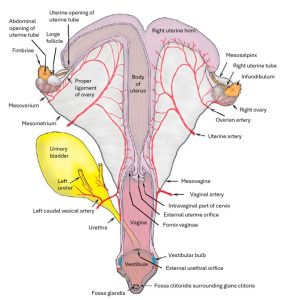

- Dorsal view of female genitalia, partially opened on midline. Smaller view shows a lateral view of a sagittal section through cervix; the fornix is ventral. 1

- Female dog reproductive tract dorsal and lateral views. 9

- Dog ovarian bursa

Observe: Examine the lateral surface of the ovarian bursa and observe the small cord-like thickening within its wall. This is the uterine tube. In female cadavers, open the ovarian bursa and examine the ovary and the infundibulum.

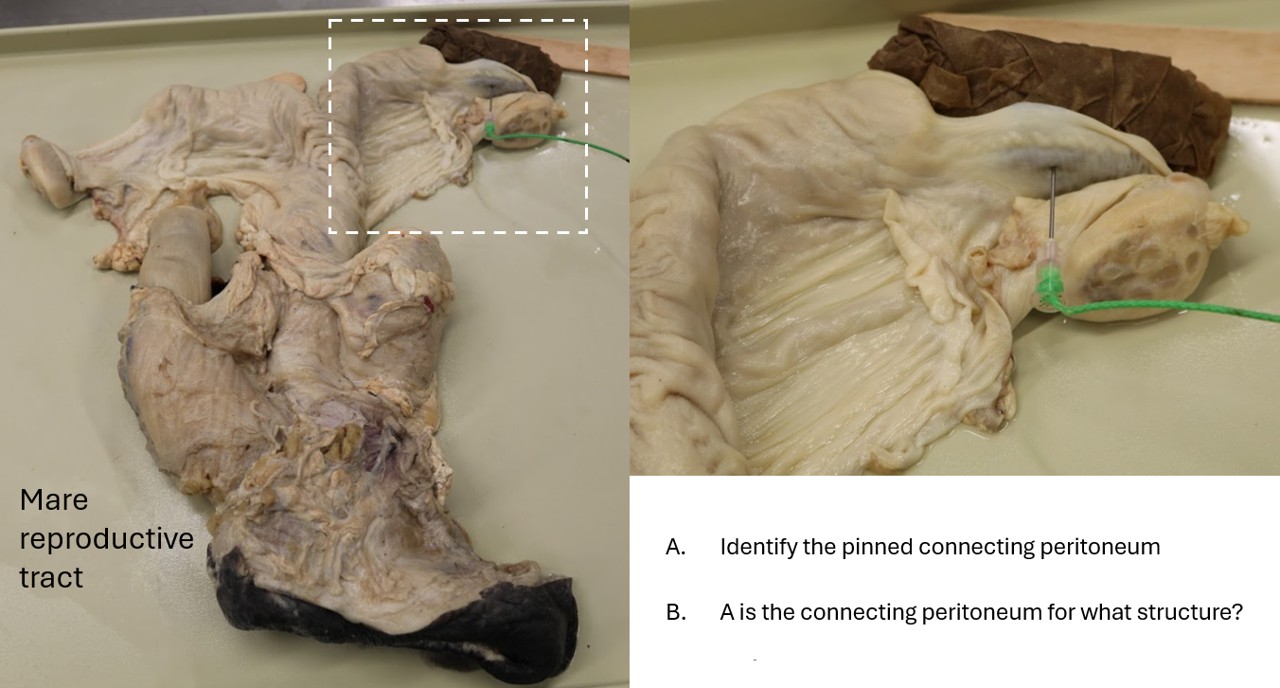

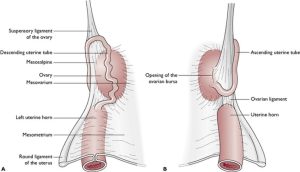

Connecting Peritoneal Structures of the Female Reproductive tract

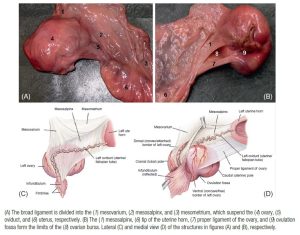

The broad ligaments of the uterus are the connecting peritoneum folds on each side that attach to the lateral sublumbar region. They suspend all the internal genitalia except the caudal part of the vagina, which is not covered by peritoneum.

Each ligament is divided into three parts: The mesometrium arises from the lateral wall of the pelvis and the lateral part of the sublumbar region and attaches to the lateral part of the cranial end of the vagina, uterine cervix, and uterine body, and the corresponding uterine horn. The mesovarium, a continuation of the mesometrium, is the cranial part of the broad ligament. It begins at a transverse plane through the cranial end of the uterine horn and attaches the ovary and the ligaments associated with the ovary to the lateral part of the sublumbar region. The mesosalpinx is the peritoneum that attaches the uterine tube to the mesovarium and forms with the mesovarium the wall of the ovarian bursa.

The suspensory ligament of the ovary joins the transversalis fascia medial to the dorsal end of the last rib. It is the thickened, fibrous, cranial margin of the broad ligament (specifically, the mesovarium). It functions to hold the ovary in a relatively fixed position. During an ovariohysterectomy (spay) this ligament is disrupted (torn, stretched, or sharply cut) at approximately its midpoint, to release the tight restraint on the ovary and thereby facilitate exteriorization of the ovary for its removal.

The proper ligament of the ovary is short and attaches the ovary to the cranial end of the uterine horn. From this point caudolaterally to the deep inguinal ring and inguinal canal, there is a peritoneal fold from the lateral layer of the mesometrium (subpart of the broad ligament connection the uterus to the body wall) that contains the round ligament of the uterus in its free border. The round ligament of the uterus, a homologue of the embryonic gubernaculum, has no function in the adult. It passes through the inguinal canal and is wrapped by the vaginal process and adipose tissue in the canine. In the queen, the vaginal process is absent and the round ligament does not extend further than the deep inguinal ring.

- Anatomy of the ovarian region of the bitch. A Lateral view. B Medial view.

-

Relations of left ovary and ovarian bursa. A, Lateral aspect. B, Lateral aspect, ovarian bursa opened.

C, Medial aspect. D, Section through ovary and ovarian bursa. 1

- Diagram of peritoneal reflections and the female genitalia.1

Observe: Identify the connecting peritoneal structures of the female reproductive tract bolded above.

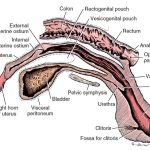

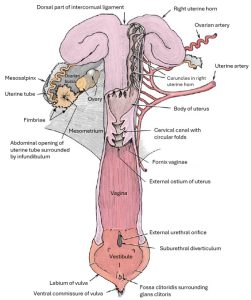

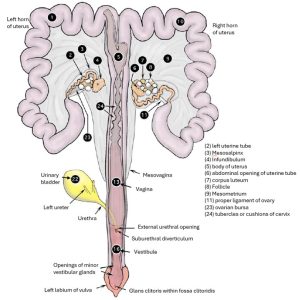

Intrapelvic female reproductive tract

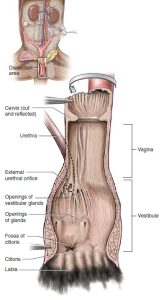

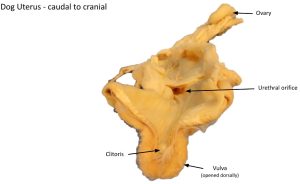

The cervix is the constricted caudal portion of the uterus. It forms a small palpable enlargement just caudal to the short body of the uterus. The cervical canal is in a nearly vertical position, with the uterine opening (internal uterine ostium) dorsal and the vaginal opening (external uterine ostium) ventral in position.

The vagina is located between the uterine cervix and the vestibule. The most cranial part of the vagina is the fornix, which extends cranial to the cervix along its ventral margin. The mucosal lining of the remaining part of the vagina is thrown into longitudinal folds that have small transverse folds. These are evidence of its ability to enlarge in both diameter and length. The longitudinal folds end dorsally at the level of the external urethral orifice, where the vagina joins the vestibule. A prominent dorsal longitudinal fold in the cranial vagina nearly obscures the external urethral ostium and makes urinary bladder catheterization difficult.

The vestibule is the cavity that extends from the vagina to the vulva. The urethral tubercle projects from the floor of the cranial part of the vestibule. The urethra opens on this tubercle. This tubercle is at the level of the ischial arch. Note its relationship to the more ventrally placed vulva.

In the floor and ventrolateral wall of the vestibule, deep to the mucosa, are two elongated masses of erectile tissue, the vestibular bulbs. They are homologous to the bulbs of the penis of the male and lie in close proximity to the body of the clitoris. They are difficult to distinguish unless your incision passed through them. See if you can find the vestibular bulbs in the prosections, but do not worry if you cannot locate them. Make sure to know these structures conceptually.

The clitoris is the female homologue of the penis. It is a small structure located in the floor of the vestibule near the vulva. It is composed of paired crura, a short body, and a glans clitoridis, which are difficult to distinguish. The glans clitoridis is a very small erectile structure that lies in the fossa clitoridis. The fossa is a diverticulum or recess as much as 2-3 cm deep in the floor of the bitch’s vestibule and should not be mistaken as the urethral opening. This anatomy is important when passing a urethral catheter in the female patient. The dorsal wall of the fossa partly covers the glans clitoridis and is homologous to the male prepuce. Note that in the queen, the vulva of the cat is small and inconspicuous in the non-estrus, non-pregnant state. The clitoris of the queen is poorly developed. The fossa clitoridis is represented by a small depression just inside the vulva. The fossa clitoridis should not be mistaken for the external urethral orifice.

FYI: The retractor clitoridis muscle, a homologue of the retractor penis in the male, originates on the first two caudal vertebrae, joins the external anal sphincter, blends with the constrictor vulvae, and continues onto the ventral surface of the clitoris.

Observe the course of the female urethra. It extends from the bladder caudodorsally over the cranial edge of the pelvic symphysis to the genital tract caudal to the vaginovestibular junction. It ends at the external urethral orifice on the urethral tubercle, which is dorsal to the rima pudendi at the level of the ischial arch.

- Female pelvic viscera, median section, left lateral view. 1

- Pelvic cavity of the female cat, in ventral view. 5

- Distal portion of female urogenital tract of the cat in ventral view. 5

- Dog uterus

- Dog clitoris

Observe: Use wet prosections of female carnivore reproductive tracts to identify the structures bolded above.

Clinical Application: Urinary Catheterization in the Female Carnivore

While passing a urinary catheter in a male carnivore is a much more commonly performed procedure, usually due to urethral obstruction, it is at times necessary to pass a urinary catheter in a female animal. Doing so is more challenging due to the location of the external urethral orifice at the boundary between the vestibule and vagina. To facilitate placement, place a finger over the catheter and keep it on the ventral wall of the vestibule as it is advanced cranially. Doing so will help to ensure the catheter enters the pelvic urethra rather than the vagina, which is located dorsal to the urethra. Advance the catheter until urine begins to flow through it.

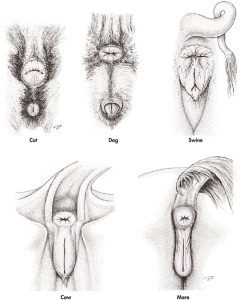

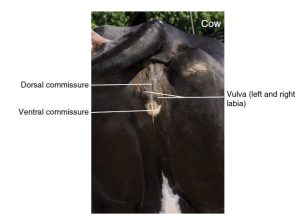

External Genitalia

The vulva includes the two labia and the external urogenital orifice that they bound, the rima pudendi. The labia fuse above and below the rima pudendi to form dorsal and ventral commissures. The dorsal commissure is ventral to a dorsal plane through the pelvic symphysis. The ventral commissure is directed caudoventrally.

- Anus and external female genital organs. 7

Observe: Identify the vulva and its dorsal and ventral commissures.

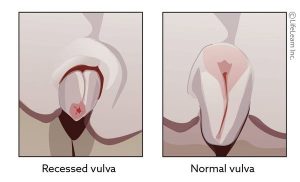

Clinical Relavance: Hooded/Recessed Vulva

A hooded vulva describes a condition where excess perineal skin folds and/or fat cover the vulva, predisposing the patient to urinary tract infections and urine scalding. To correct this condition, a surgical procedure called a vulvoplasty or episioplasty may be performed.

- Hooded (recessed) vulva

- Hooded vulva

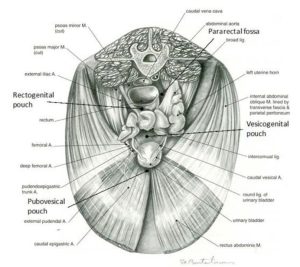

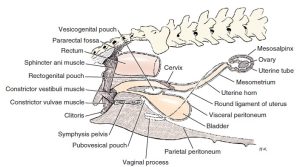

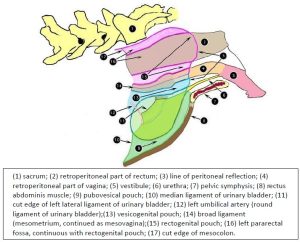

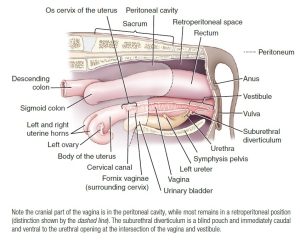

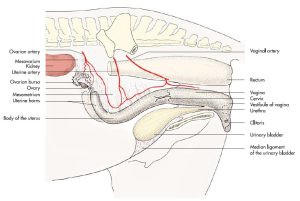

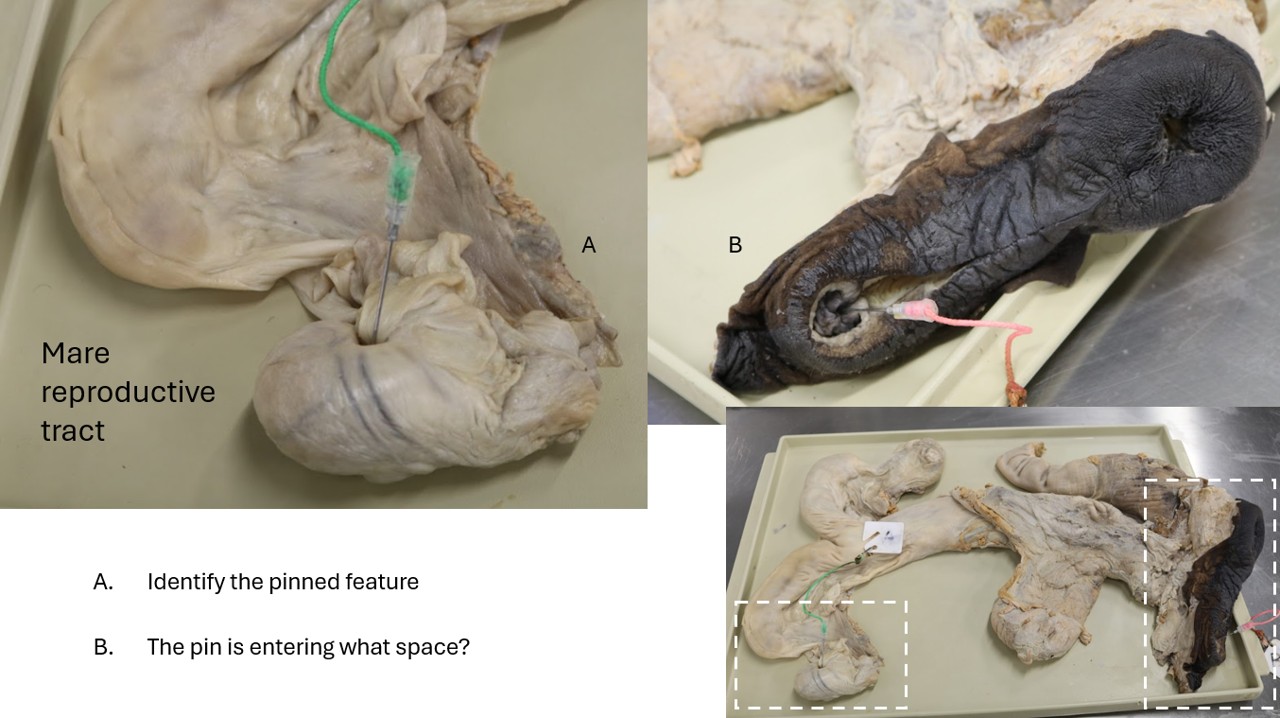

Peritoneal Pouches

From dorsal to ventral, the viscera of the pelvic cavity are the rectum, reproductive tract [vagina (females) or genital fold (males)], and the urinary bladder.

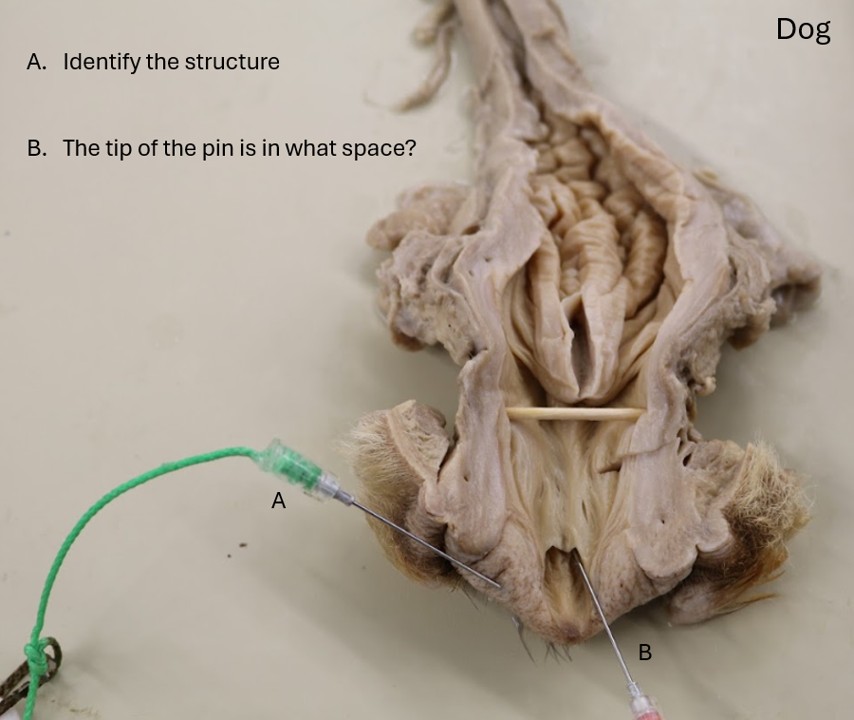

The parietal peritoneum of the abdominal cavity extends part way into the pelvic cavity and reflects back on itself, forming blind-ended pouches around and between the viscera of the pelvic cavity. This line of peritoneal reflection marks the caudal extent of the peritoneal cavity. Examine the pelvic cavity of the cadaver and identify the organs present (transected rectum, reproductive organs, urinary bladder). Then identify the peritoneal pouches by boldly passing your hand caudally around the pelvic cavity viscera and between the connecting peritoneums. The rectogenital pouch is between the rectum and genital tract (uterus in female, genital fold containing ductus deferens in male); on either side of the rectum and mesorectum (connecting peritoneum of the rectum) continuing dorsally from the rectogenital pouch is the pararectal fossa; between the genital tract and the urinary bladder is the vesicogenital pouch; and between the pubis and the urinary bladder (ventral to the lateral ligaments of the bladder) is the pubovesical pouch.

- Diagram of peritoneal reflections and the female genitalia.1

- Extensions of peritoneum into pelvic cavity of bitch, left lateral view. 2

- Female goat pelvic viscera at pelvic inlet. 22

- Pelvic peritoneal pouches in a female (above) and male (below) animal. 7

- Pelvic cavity and peritoneal structures of the cow and mare. 6

- Cow peritoneum. 9

Observe: Examine the pelvic cavity of all cadavers and identify the organs present (transected rectum, reproductive organs, urinary bladder). Then identify the peritoneal pouches by boldly passing your hand caudally around the pelvic cavity viscera and between the connecting peritonea.

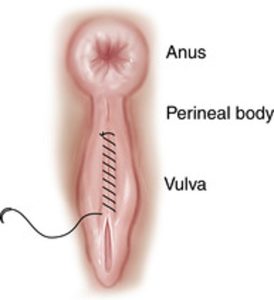

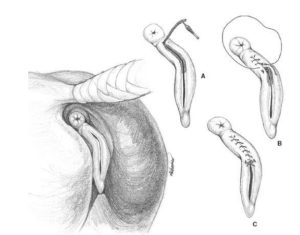

Clinical Application: Rectovaginal Fistulas/Rectal Tears

Pay particular attention to the caudal extent of the rectogenital pouch (it is caudal to the cervix). The prognosis for tears to the rectum (iatrogenic during palpation per rectum, or from breeding and parturition accidents) and tears to the vagina (breeding or more commonly parturition injuries) is in large part dependent on whether the tear is cranial to the caudal extent of the pouch and thus communicating with the peritoneal cavity. This is especially important in the mare where foaling injuries from a misdirected foot can cause tears through the dorsal vaginal wall and on into the rectum. If the perforation occurs cranial to the line of peritoneal reflection and involves the rectum, then the peritoneal cavity will become contaminated with fecal materal, an emergency condition that may be fatal for the horse due to the severe sepsis that likely ensues. A tear caudal to the peritoneal reflection will be considered retroperitoneal and therefore much less life-threatening but it still typically requires significant attention. If the foot is subsequently retracted back into the vagina before parturition progresses a rectovaginal fistula will result; if the foot stays in the rectum, a 3rd degree perineal laceration occurs as the foal is born, tearing the vaginal roof, the intervening perineal tissues (the perineal body), and the rectal floor all the way out through the anal sphincter and skin surface. Perineal lacerations are graded on their severity and 1st and 2nd degree lacerations do not enter the rectum and are more readily managed.

Examining a foaling injury about 3 months post foaling in a mare.

Q: What is your diagnosis?

Ungulate Female Genital Tracts

Observe: Identify the bolded structures on cadavers where visible, and otherwise make liberal use of the wet reproductive tract specimens to understand this anatomy on all of the female ungulate species.

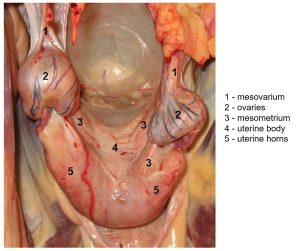

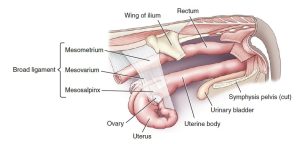

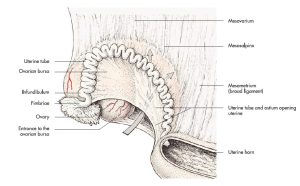

Broad ligament review

The broad ligaments are the two connecting peritoneums that attach the female reproductive tract to the body wall. Each ligament is divided into several parts, named according to the specific part of the internal genitalia supported by the ligament: the mesovarium directly supports the ovary and its cranial, thickened border is the suspensory ligament of the ovary; the mesosalpinx (a fold detached from the mesovarium) which contains the uterine tube and forms the lateral wall of the ovarian bursa; the mesometrium, which supports the uterus. The round ligament of the uterus generally passes from the tip of the uterine horn to the deep inguinal ring in a lateral fold of the broad ligament (mesometrium part).

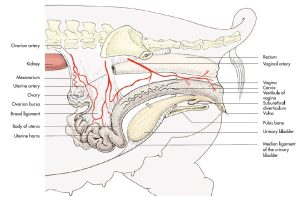

- Dorsoventral view of the equine female reproductive tract. 9

- Lateral view of the mare reproductive tract. 9

- The broad ligament suspends the genital tract from the abdominal and pelvic wall. 9

- Broad ligament of the cow. The broad ligament is formed from the confluence of the mesometrium, the mesovarium, and the mesosalpinx. 9

Observe: Examine dissected cadavers to identify this anatomy: broad ligament- mesovarium, mesosalpinx, mesometrium, round ligament of the uterus (mare, maybe doe,), suspensory ligament of the ovary.

Ovaries and Associated structures

Note that the ovaries of the mare are relatively large structures and, in the adult, are characterized by their unusual kidney shape. This unique shape is produced by the presence of a distinct depression, the ovulation fossa, which develops as the ovary matures. As the name implies, rupture of the follicle (ovulation) typically occurs at or near the ovulation

fossa.

The ovaries are tightly connected to the uterine horns via a band of fibrous tissue and smooth muscle, the proper ligament of the ovary. In the cow, both the mature follicle and corpus luteum project prominently from the surface of

the ovary, and can be palpated rectally.

The ovarian bursa is a cavity that surrounds the ovary, enclosed by the mesovarium, mesosalpinx and ovary. Unlike that of the dog, the ovarian bursa of domestic ungulates is rather open. That is, the mesosalpinx, which contains the uterine tube, only loosely envelops the ovary and can be easily reflected to expose the ovary. The uterine tube, with its funnel-shaped beginning (the infundibulum with finger-like fimbriae around its margin) passes from adjacent to the ovary to its opening into the tip of the uterine horn. In the center of the infundibulum is the abdominal opening of the uterine tube, through which ova pass.

- Ovary, uterine tube and ovarian bursa of an cow. 7

- Ovary, uterine tube and ovarian bursa of an mare. 7

- Cow and mare reproductive organs. 6

- Horse ovary and broad ligament. 9

- Cow ovarian bursa. 38

- Bovine ovary (cow). Ovarian bursa opened. 12

Observe: Identify the following structures as described above, in all of the ungulate species: ovary, ovarian bursa, ovulation fossa (mare), uterine tube, infundibulum (with fimbriae), abdominal opening of the uterine tube, ovarian a., ovarian v., proper ligament of ovary.

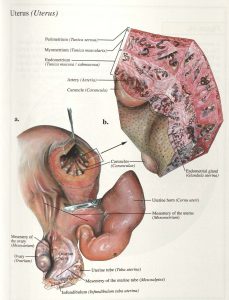

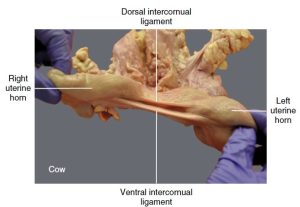

Uterus

The proximal halves of the uterine horns lie close together and are connected by the intercornual ligament(s) in ruminants. In the cow, distinct dorsal and ventral intercornual ligaments are present. During rectal palpation, the dorsal intercornual ligament can be used as a finger hold to bring the non-gravid uterus into the hand for examination. In the doe and ewe a singular intercornual ligament is present.

The uterine body is of variable length between the species.

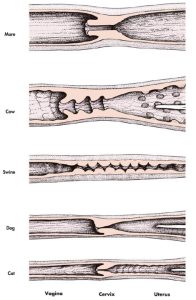

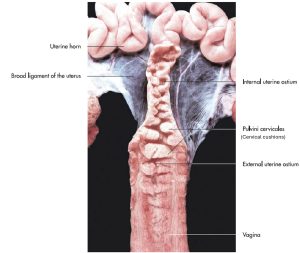

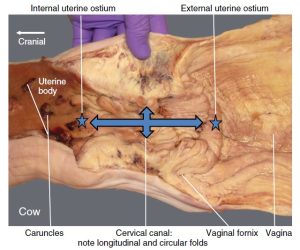

Cow: The cervix of the cow is firm and thick-walled, which allows it to be easily identified during rectal palpation of the genital tract. Note that it has three or four prominent circular folds that project into the lumen of the cervical canal. When the cervix is closed, these folds interdigitate with one another and make passage of an insemination pipette virtually impossible. During pregnancy, the canal is completely sealed with a tight-fitting mucous plug.

Goat: The cervical canal of the small ruminants has more circular folds than that of the cow.

- Genitalia of cow, partially dissected, dorsal view. 2

- Cow reproductive tract. 38

- Cow uterus and ovary. 38

- In situ overview of the bovine (cow) reproductive tract. 12

-

Bovine (cow)

dorsal and ventral intercornual ligaments: cranial view. Small ruminants have a single intercornual ligament. 12

Sow: The cervix of the sow is especially long, and the canal is closed by the interdigitation of a series of prominences (cushions), from the cervical wall into the lumen.

- Genitalia of sow, partially dissected, dorsal view. 2

- Female genital organs of the sow. 7

- Uterus of a sow after injection of the arteries (on the left, in red) and lymph vessels (on the right, in dark blue). 7

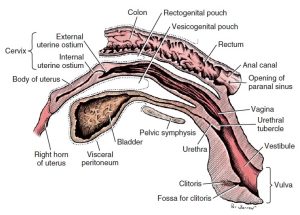

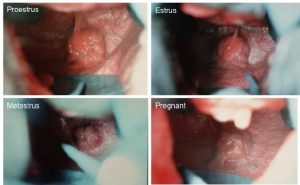

Mare: In the mare, the appearance of the cervix varies considerably and, when viewed through a vaginal speculum, is used to evaluate the stage of the reproductive cycle. The cervix opens into the uterine body at the internal uterine (or cervical) ostium and to the vagina at the external uterine (or cervical) ostium.

- Genitalia of mare, partially dissected, dorsal view. 2

- Dorsoventral view of the equine female reproductive tract. 9

- Female genital organs of the mare. 7

Observe: In the cow, identify the intercornual ligament, and identify the uterine body (short in ruminants, long in mare), cervix, and internal and external uterine openings (ostium) in all of the ungulates. Identify the cervical cushions (sow).

Vagina

The vagina has circular and longitudinal mucosal folds, allowing for distension during parturition. Note the projection of the cervix into the vagina (referred to as the cervix portio vaginalis). Identify the recess around the projecting cervix – it is known as the vaginal fornix. The vaginal fornix must be avoided when attempting to insert an insemination pipette into the external ostium of the uterus. In the small ruminants, the intravaginal part of the cervix lies in a ventral depression so that the external uterine ostium is more on a level with the ventral floor of the vagina. The sow has no intravaginal portion of the cervix, and therefore no fornix vaginae, the sow vagina is relatively long and is characterized by prominent longitudinal folds

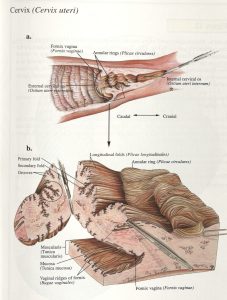

- Uterine cervix of different domestic animals. 7

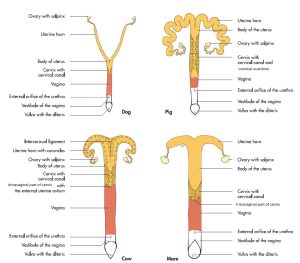

- Female genital organs of the domestic mammals. 7

- Endoscopic view of mare cervix at different phases of reproductive cycle. onlineveterinaryanatomy.net

- Cow vagina. 38

- Cow cervix. 38

- Vagina and uterine cervix of a sow (partially opened in midline). 7

-

Bovine (cow) cervix opened dorsally to demonstrate the cervical canal, and the internal

(towards the uterine body) and external (toward the vagina) uterine orifices. 12

Observe: Identify the vagina in all species and the vaginal fornix (mare, cow, doe).

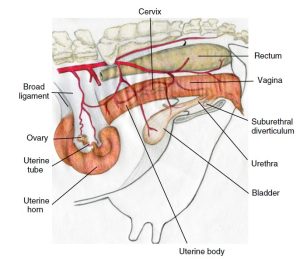

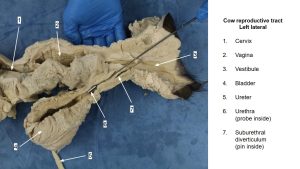

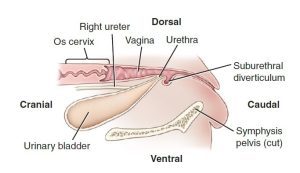

Vestibule and urethra

The vestibule extends from the vagina to the vulva. Locate the cranial extent which is identified by the external urethral orifice of the urethra, covered partially by a transverse fold which is continued either side as a remnant of the hymen in the mare. The vestibule of the pig is long (have you picked up by now that basically the sow reproductive tract is looooonnngg? Except for the short uterine body!), so the external urethral orifice is located relatively far cranially. In the ruminant and sow, a blind recess is present ventral to the external opening of the urethra, the suburethral diverticulum. Like almost everything else in the female urogenital tract of the pig, the urethra is long, so that only the neck of the urinary bladder is located within the pelvic cavity. The urethra of the mare is especially short and wide (enough so that a relatively small, well lubricated hand can be gently passed through and into the bladder to retrieve a cystic calculus! Such calculi are uncommonly identified in mares, one reason being that any developing stones are readily passed out in the urine).

FYI – In the mare, there is erectile tissue in the lateral walls of the vestibule that is consolidated to form the right and left vestibular bulbs. Although erectile tissue is present in the other domestic ungulates, it is more diffuse. In the dorsal, lateral and ventral walls of the vestibule, depending on the species, small openings indicate the presence of vestibular glands (major and minor vestibular glands are described). Major vestibular glands represent the female homologues of the bulbourethral glands of the male.

- Cow reproductive tract

Observe: Identify the vestibule, urethra, external urethral orifice in all the ungulates and the suburethral diverticulum in the ruminant and sow.

Clinical relevance: suburethral diverticulum in passing a urinary catheter or artificial insemination pipette

The suburethral diverticulum must be taken into account during catheterization of the urinary bladder of the ruminant or sow. How would you avoid it?

- The suburethral diverticulum is ventral to the urethra in bovids and must be avoided when catheterizing the bladder. 9

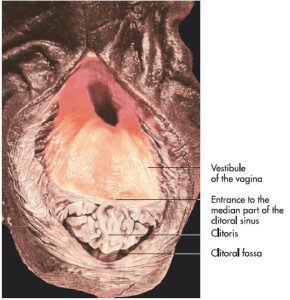

Vulva and clitoris

The labia of the equine vulva are rounded, and the vulvar cleft is unique in that the ventral commissure is rounded and the dorsal commissure pointed, just the opposite of the other domestic mammals.

In the cow, the small glans clitoridis is located just inside the ventral commissure. The glans clitoridis of the sow, is also rather poorly developed and is concealed in its small fossa, just inside the ventral commissure of the vulva.

The clitoris of the mare is large and contains a considerable quantity of erectile tissue. Like its male homologue (glans penis), the glans clitoridis of the horse is better developed than that of other species. The glans clitoridis is located within the fossa clitoridis. The glans clitoridis has a median sinus clitoridis (maybe referred to as the fossa glandis) and two inconstant lateral clitoral sinuses present within its structure (in the gelding/stallion, the fossa glandis is located in the glans penis and surrounds the urethral process at the end of the urethra).

- Vulva of a mare. 7

- External genitalia of the cow. 12

- Anus and external female genital organs. 7

Observe: Identify the vulva, vulvar cleft, labia, clitoris, glans clitoridis, fossa clitoridis (mare) and sinus clitoridis (mare).

Clinical relevance: Contagious equine metritis and “Winking”

The clitoral sinuses have been shown to harbor the infectious organism responsible for contagious equine metritis (Taylorella equigenitalis).

During estrus or following urination, mares can voluntarily contract their ischiocavernosus muscles and expose the glans clitoridis, a phenomenon that, for lack of a more appropriate term, is known as “winking.”

Clinical Relevance: Caslick’s vulvoplasty

In the mare, the relationship of the vulva and vestibule to the ischial arch and anus is important. Poor perineal conformation, loss of body condition, and increasing age can result in the vulva and anus drawing cranially or ‘sinking’, as if they were falling into the pelvic cavity. This predisposes to fecal contamination of the vulva and a loss of normal vulva sealing such that air and contaminates can enter the vestibule and vagina. To compound matters, the vulva tends to fall in and out of the pelvic outlet as the mare walks. This to-and-fro motion tends to pump air into the vestibule and vagina (‘windsucking’), causing a pneumovagina.

To manage this condition, many brood mares undergo a procedure known as a Caslick’s vulvoplasty (simply, a ‘Caslick’s’). The vulvar cleft is sutured closed, except for an opening at the ventral commissure, to allow for urination. The vulva is reopened before parturition to avoid excessive foaling trauma!

- Caslick’s surgery on a mare.

- Caslick’s episioplasty or vulvoplasty to manage ‘windsucking’ secondary to poor perineal conformation. veteriankey.com

Clinical Relevance: Urovagina

In older mares, poor perineal conformation and poor body condition can also result in urine pooling in the vagina (urovagina), resulting in vaginitis and possibly metritis. ‘Urethral extension’ surgery can help and involves using the transverse fold at the external urethral orifice as a flap of tissue that can be sutured caudally to additional flaps of tissue to create a tunnel leading from the urethral orifice. This tunnel directs the urine more caudally and limits retrograde flow and pooling of urine back into the vagina.

- Mare urovagina.

Review videos

Female dog reproductive tract, cadaver and wet specimen – 16 min

Female dog repro, wet specimen – 5 min

Dr. Gallenstein explains the anatomy of a dog spay – 8 min

Mare Pelvic Cavity – 15 minutes

Mare repro tract – 7 minutes

Cow repro tract – 8 minutes

Sow repro tract – 7 minutes

Udder, placenta – 6 minutes

Placentation review – 10 minutes

Terms

| Boundaries of the Pelvic Cavity | ||

| Osteology | Features | Species differences/comments |

| Pelvic girdle/pelvis | ||

| Pelvic symphysis | ||

| Os coxae | ||

| Ilium | Wing of the Ilium | |

| Tuber coxae | ||

| Body of the Ilium | ||

| Ischium | Ischiatic tuberosity | |

| Ischiatic arch | ||

| Obturator foramen | ||

| Greater ischiatic notch | ||

| Lesser ischiatic notch | ||

| Pubis | Body of the Pubis | |

| Sacrum | Wings of the sacrum | |

| Promontory | ||

| Pelvic girdle (pelvis) | Pelvic inlet (and define boundaries) | |

| Pelvic outlet (and define boundaries) | ||

| Pelvic symphysis | ||

| Sacroiliac joint | ||

| Sacrotuberous ligament | Dog only | |

| Sacrosciatic ligament | aka broad sacrotuberous ligament | Ungulates only |

| Greater ischiatic (sciatic) foramen | ||

| Lesser ischiatic (sciatic) foramen | ||

| Sciatic nerve | ||

| Pelvic canal | ||

| Pelvic inlet | ||

| Pelvic outlet | ||

| Pelvic diaphragm mm. | Levator ani and coccygeus mm. | |

| Ischiorectal fossa | Depression between lateral aspect of pelvic diaphragm mm. and medial aspect of ischiatic tuberosity | |

| Inguinal Canal and Peritoneum | ||

| Term | Features | Species differences/comments |

| Inguinal canal | Short fissure between superficial inguinal ring and deep inguinal ring | |

| Superficial inguinal ring | Slit in external abdominal oblique (EAO) | |

| Deep inguinal ring | Caudal edge of Internal abdominal oblique m. | Cranial boundary |

| Inguinal ligament (caudal edge of EAO) | Caudolateral boundary | |

| Lateral edge of the rectus abdominus muscle | Medial boundary | |

| Parietal peritoneum | Internal lining of abdominal cavity (very thin and shiny) | |

| Transversalis fascia | External lining of abdominal cavity (thicker white, fibrous layer) | |

| Ovaries, Uterus, and Associated Structures | ||

| Term | Features | Species differences/comments |

| Ovaries | ||

| Ovarian bursa | ||

| Ovulation fossa | ID in mare only | |

| Mesovarium | ||

| Mesosalpinx | ||

| Infundibulum | Present in all. ID in ungulates. | |

| Uterus | ||

| Uterine horns | ||

| Intercornual ligaments | Present in many species; there may be one or two. Clinically significant in bovine for rectal palpation during pregnancy checks. | ID in bovine only. |

| Uterine tube | ||

| Abdominal opening of the uterine tube | ||

| Uterine body | ||

| Cervix | ||

| Internal uterine ostium | ||

| External uterine ostium | ||

| Intrapelvic Female Reproductive Tract | ||

| Term | Features | Species differences/comments |

| Vagina | ||

| Vaginal Fornix | Not in the sow | |

| Vestibule | ||

| Vestibular bulbs | Do not ID. Know what and where they are | |

| Urethra | ||

| Suburethral diverticulum | Ruminant and Sow only | |

| External urethral orifice | ||

| Urethral tubercle | ||

| Vulva | ||

| Labia | ||

| Vulvar cleft | ||

| Ventral commissure | ||

| Dorsal commissure | ||

| Clitoris/Glans clitoridis | ||

| Fossa clitoridis | ||

| Sinus clitoridis | ID in mare only | |

| Connecting Peritoneal Structures of the Female Reproductive Tract | ||

| Term | Features | Species differences/comments |

| Broad ligament | ||

| Mesometrium | ||

| Mesovarium | ||

| Mesosalpinx | ||

| Suspensory ligament | ||

| Proper ligament of the ovary | ||

| Round ligament of the uterus | ||

| Vaginal Process | dog only | |

| Peritoneal Pouches | ||

| Term | Features | Species differences/comments |

| Rectum | ||

| Line of peritoneal reflection | ID in mare only | |

| Urinary bladder | ||

| Rectogenital pouch | ID in mare only | |

| Mesorectum | ||

| Pararectal fossa | ID in mare only | |

| Vesicogenital pouch | ID in mare only | |

| Pubovesical pouch | ID in mare only | |