Lab 3A & 4A: Dentistry and Upper ALT Diagnostic Imaging Anatomy

Learning Objectives

- Identify parts of the tooth and identify the different types of teeth.

- Identify the different surfaces of the tooth.

- Recall the innervation of the teeth and identify the nerves that provide this innervation.

- Age horses based on dental eruption and wear.

PPT supplement to lab guide (also linked in moodle) – VET924 Aging horse by teeth sp2025

Lab Instructions

Ingesting food is one of the fundamental ways in which a species interacts with its environment. Chewing is also the first step in digestion. Teeth then must be able to effectively meet these two demands; ingestion and chewing. Unsurprisingly, the functional demands on the teeth of one diet (say, meat-eating in the carnivores) can be radically different than those of a different diet (herbivory, for instance). Thus, diet and the shape of the teeth and even how they come together when the mouth is closed are intimately related. Therefore, while all teeth have some fundamental anatomical features that make them similar, nevertheless we will need to discuss the teeth of our carnivores separately from those of the ungulates.

Basic Anatomy of a Tooth

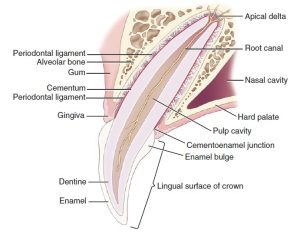

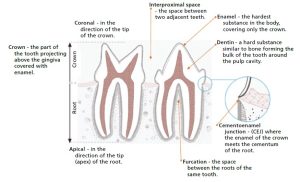

Each tooth possesses a crown and a root (or roots), which is/are embedded in the alveolar bone of the jaw. The junction of the root and crown is the neck of the tooth.

Covering the crown is a thin layer of mostly inorganic mineral called enamel (enamel is the hardest substance found in the body!). Deep to the enamel is the dentin, which comprises the majority of the mass of the tooth. Dentin is more similar in its composition to that of the other bones of the skeleton. As the crown naturally wears down with age, the dentin may be exposed to varying degrees.

The dentin of the neck and root is covered by another tissue known as cementum. Cementum creates a rough surface on the neck and root to which the periodontal ligaments attach and anchor the root into the jaw.

Observe: Identify the parts of the tooth, as well as enamel, dentin, and cementum, in any of the skulls located around the lab.

Inside of the root is a hollow cavity known as the pulp cavity. The pulp cavity is full of blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves, known collectively as the pulp. The space between roots is known as the furcation. While usually filled by alveolar bone, an exposed furcation indicates periodontal disease.

- Section through a superior canine of an adult dog. 1

- Tooth anatomy and direction nomenclature. 35

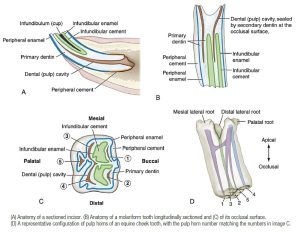

- Anatomy of a horse tooth. 9

Observe: Refer to one of the plastic tooth models to identify the pulp cavity.

The teeth are arranged in superior (upper) and inferior (lower) arches that face each other. In all of the species we study here, the inferior arch is narrower than the superior (a condition known as anisognathism).

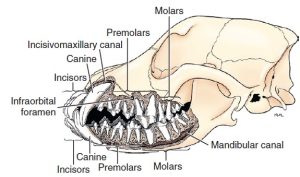

The upper teeth are contained in the incisive and maxillary bones. Those whose roots are embedded in the incisive bone are known as the incisors. Caudal to these and separated from them by a space is the canine. Behind this are the cheek teeth, which are divided into premolars and molars. The inferior incisors, canines, and cheek teeth all have their roots set in the mandible. Some of the teeth usually meet the teeth of the opposite arch when the mouth is closed. However in the carnivore, the first three premolars fail to meet during normal closure, and the opening between the teeth is known as the “premolar carrying space”.

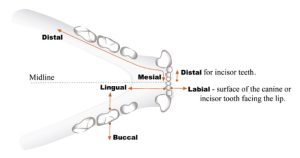

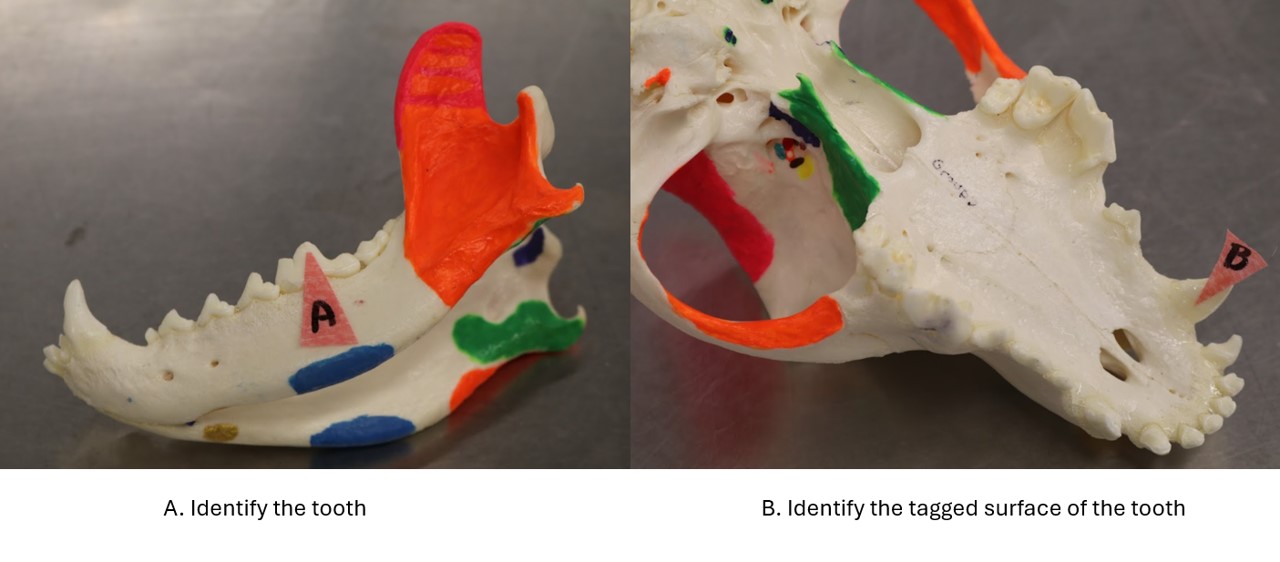

The outer surface of the teeth is the vestibular surface, which can be also be referred to as the labial surface if looking at incisors or canines, or as the buccal surface if looking at premolars or molars. The inner surface is the lingual surface for mandibular teeth or the palatine surface for maxillary teeth. The side of a tooth that lies in contact with or faces an adjacent tooth is referred to as the mesial surface if it faces/is in contact with the tooth rostral to it; or as the distal surface if it faces/is in contact with the tooth caudal to it. On the first incisor, the mesial surface is next to the median plane. Finally, the surface of the tooth that faces the opposite dental arch (either up or down) is known as the occlusal surface.

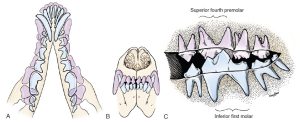

- Jaws and teeth of an adult dog. 1

-

A, Superimposition of superior (pink) and inferior (blue) dental arches. B, Bite of the incisor and canine teeth.

C, Medial view, right dentition. 1

- Directions in the oral cavity. 35

Observe: Identify the different types of teeth and their different surfaces in any of the skulls provided around the lab.

The Carnivore Dentition

Recall the dental formula describes one half of the mouth, with the number of Incisors: Canines: Premolars: Molars of the maxillary teeth presented over the numbers of those teeth in the mandible.

The dental formula for the permanent teeth of the dog is as follows:

3:1:4:2/3:1:4:3

The dental formula for the permanent teeth of the cat is as follows:

3:1:3:1/3:1:2:1

The dentitions of most carnivorans (that is, mammals in the Order Carnivora) are noted by the upper fourth premolar and lower first molar taking the shape of large blades, which when the jaw is closed, act like scissors capable of slicing through flesh. The upper fourth premolar and lower first molar are together known as the carnassial teeth, or simply “carnassials”.

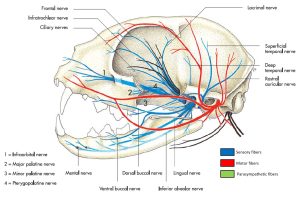

Innervation of the Teeth

When performing dental procedures, it is frequently necessary to block the nerves that innervate the teeth for pain management. Let’s revisit the nerves that innervate the upper and lower teeth and their anatomical pathways in order to review where we may apply the anesthetic.

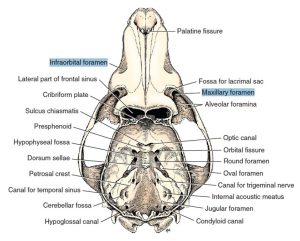

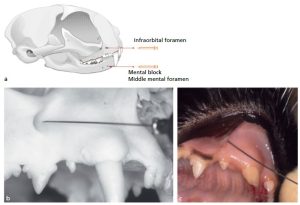

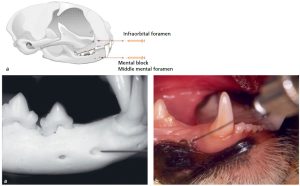

Observe: Using a skull of any species, identify the infraorbital canal. Recall that the caudal end of the infraorbital canal is represented by the maxillary foramen, and the rostral end by the infraorbital foramen.

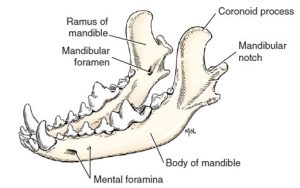

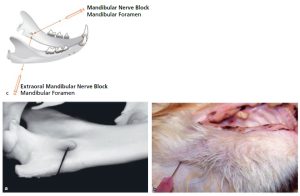

Now, with a mandible (or at least one half [left or right] of a mandible), identify the mandibular canal. Recall that the entry to the mandibular canal caudally is represented by the mandibular foramen. The canal terminates rostrally with the mental foramina (usually one or two per side).

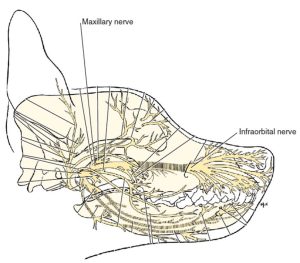

Time to review some nervous system anatomy! Passing through the maxillary foramen into the infraorbital canal is the maxillary nerve. In the infraorbital canal, the maxillary nerve splits into a series of nerves which provide cutaneous innervation to the rostral, dorsal, and lateral face. Specifically in the context of the innervation of the teeth, the infraorbital nerve splits from the maxillary nerve in the infraorbital canal. Small branches known as the superior alveolar branches then pass ventrally from the infraorbital nerve to enter the roots of each tooth. The infraorbital then passes rostrally through the infraorbital foramen and provides sensation to the upper lips and snout.

Observe: In the half of the head that was used for deep dissection, identify the maxillary nerve just caudal to the maxillary foramen. Identify the infraorbital nerve as it exits the infraorbital foramen. Appreciate that the infraorbital nerve innervates the maxillary teeth on the ipsilateral side.

Moving to the mandibular teeth, the inferior alveolar nerve arises from the mandibular nerve on the lateral aspect of the pterygoid muscles and passes through the mandibular foramen on its course through the mandibular canal. Whilst in the mandibular canal, the inferior alveolar nerve supplies branches which enter the roots of the mandibular (or lower) teeth on the ipsilateral side. Near the end of the mandibular canal, extensions of the inferior alveolar nerve exit the mental foramina as the mental nerves, which innervate the lower lip and chin.

Observe: Returning to the half of the head that was used for deep dissection, identify the inferior alveolar nerve as it enters the mandibular foramen. Appreciate that the inferior alveolar nerve innervates the mandibular teeth on the ipsilateral side.

- Dog skull with calvaria removed, dorsal aspect. 1

- Path of the maxillary nerve in the dog. 1

- Primary branches of the trigeminal nerve in the cat. 7

- Left and right mandibles of the dog, dorsal lateral aspect. 1

- Maxillary & inferior alveolar nn.

- Infraorbital nerve

Clinical application

This box will be used for information regarding proper placement of the needle for dental nerve blocks.

- Infraorbital nerve block of the cat. 35

- Mental nerve block of the cat. 35

- Mandibular nerve block of the cat. 35

The Ungulate Dentition

Hypsodont (long crowned) teeth have no clearly distinguishable neck. These teeth consist of a body (that has a clinical and reserve crown) and roots, and in the horse, hypsodont teeth grow to a certain length, then stop growing, but continue to erupt until the tooth (or horse!) expires. Brachydont teeth have short crowns and relatively long roots, and stop erupting once fully grown.

- Hypsodont (left) and brachyodont (centre, right) teeth. 7

Observe: Identify in the horse:

- Hypsodont teeth

- Tooth surfaces [occlusal, lingual, palatal, vestibular (buccal or labial), mesial (rostral), distal (caudal)],

- Apex (apices)

- Crown (clinical and reserve)

- Wolf teeth

- Interdental/interproximal space or Diastema (bars of mouth is the very wide diastema)

- Incisors, canines, premolars, molars

- Enamel, cementum, dentine

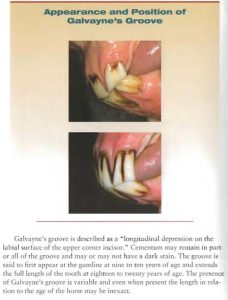

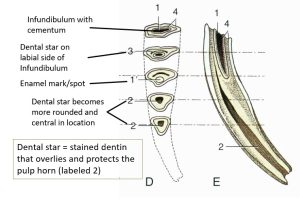

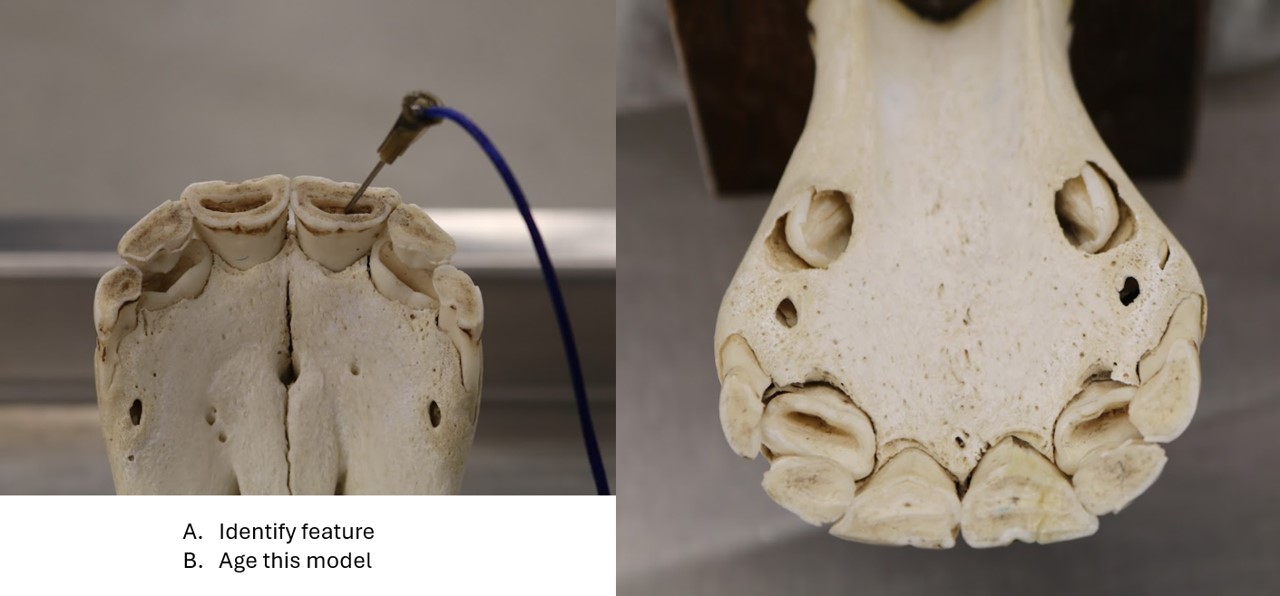

- Infundibulum, dental star, enamel spot, Galvayne’s groove.

Horse deciduous dental formula:

3:0:3:0/3:0:3:0

The permanent dentition of the horse varies depending on the sex of the horse (note that males can have canines while females do not) and the presence or lack thereof of the first premolar (i.e, the “wolf tooth”).

Horse permanent dental formula

3:0(1):3(4):3/3:0(1):3(4):3

Estimating the Age of a Horse with its Teeth

Being able to estimate age within a (relatively) narrow range can be of use to owners of unregistered horses or horses whose age is unknown for any reason. Managing the horse’s health and nutrition is often directly related to its age and dental wear, which means it’s important for the veterinarian to have a general understanding of how the horse’s mouth changes with age.

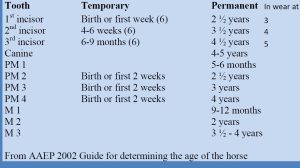

Estimating the age of a horse based on its teeth comes down primarily to two criteria: eruption time of the deciduous and permanent teeth, and the wearing down of those teeth after eruption. Of the two, eruption time is fairly reliable as it is mediated by gene expression and is related to growth patterns that are mostly consistent between individuals. Tooth wear is much less reliable, as its progression is mediated by external factors, such as diet and environment.

Since it is much easier to observe the horse’s incisors, we tend to focus our efforts on aging with the incisors. It is important to be able to distinguish the deciduous from the permanent incisors. Deciduous incisors have a notable neck, and are smaller, with numerous grooves (resulting in a “clam-shell” appearance). The permanent incisors on the other hand have no neck, are larger, and typically have only one central groove filled with a stained cementum. Knowing these differences will allow us then to observe the presence (and/or absence) of specific deciduous and permanent incisors and line up the known eruption times of these teeth with the approximate age of the horse. Let’s take a look at these eruption times in the chart below.

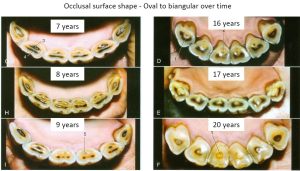

In addition to the eruption timing of these teeth, the wearing down of their occlusal surfaces is also informative as it takes time for these teeth to wear. Notice that as the teeth wear, a flat surface of dentin is more apparent relative to the newly erupted, unworn teeth. The occlusal surfaces of the incisors are noticeably in wear after approximately 6 months post eruption. *Important note: occlusal surface observations are made on mandibular incisors only!*

- Deciduous incisor eruptions

- Permanent incisor eruptions

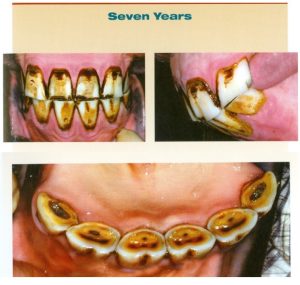

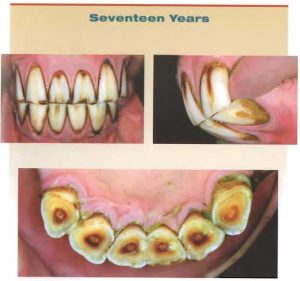

After all of the permanent incisors have erupted, our aging methods become solely based on wear, and thus are much less reliable. As a general rule, the infundibula for the first, second and third incisors are worn away around ages 6, 7, and 8, respectively, leaving a dental mark as its last remnant. After the dental mark disappears, a dental star appears; the dental star is a spot of stained dentin that overlies and protects the pulp cavity. Notice also that as the horse approaches age 10, the incisors begin to change shape (when viewed from the occlusal perspective) as they continue to wear down, going from oval to more biangular over time.

- Occlusal surface shape. 7

- Seven year old.

- Seventeen years old.

- Galvayne’s groove

- Horse tooth cross section

For a full “catalog” of ages, see the American Association of Equine Practitioners “Guide for Determining the Age of the Horse.”

Observe: Be able to age a horse by incisor eruption (+/-6months) up to 5 years; or classify as in the 5-10 years range, or 20 years and older.

Clinical Application

Equine dental health and disease represents a significant portion of equine wellness care in practice.

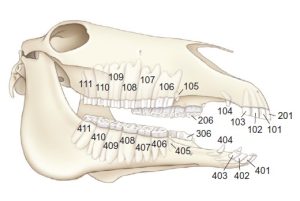

FYI – Modified Triadan numbering system for teeth

Teeth are efficiently identified and recorded using the modified Triadan numbering system across the species. This system is used routinely in veterinary dentistry. The diagram below indicates the assigned tooth number. Temporary (deciduous) teeth are numbered too, starting with 5, 6, 7, and 8 going around clockwise from the upper right side. For example, the 707 tooth is the temporary left third mandibular premolar, whereas the 502 is the temporary right maxillary second incisor. Recall in the horse there are no temporary canines, wolf teeth or molars.

-

An open-mouth view of the dog with teeth identified by the

anatomic and Modified Triadan System of nomenclature. 1

- The modified Triadan numbering of teeth of the horse. 9

Observe: Identify in the ruminant:

- Dental pad

- Incisors, canines, premolars, molars

Permanent dental formula of the ruminant:

0:0:3:3/4:0:3:3

NCSU Skills video – Aging ruminants

Observe: Identify in the pig:

- Tusks (canines)

- Needle teeth (deciduous canines and third incisors)

Permanent dental formula of the porcine:

3:1:4:3/3:1:4:3

Clinical relevance:

Tusks of boar continue to grow throughout life and may need to be trimmed; dental disease (e.g. tusk abscess) may be treated in companion pigs; ‘needle teeth’ may be cut off at birth to reduce trauma to sow.

Potbelly pig with ingrown tusk (LOUD!)

Review videos

Horse teeth – 43 min

Terms

| Terms | |

|---|---|

| Crown | |

| Root | |

| Furcation | |

| Neck | |

| Alveolar bone | |

| Enamel | |

| Dentin | |

| Cementum | |

| Periodontal ligament | |

| Pulp cavity | |

| Pulp | |

| Anisognathism | |

| Incisor | |

| Canine | |

| Premolar | |

| Molar | |

| Permanent dental formulae of all species | |

| Vestibular surface | |

| Labial surface | |

| Buccal surface | |

| Lingual surface | |

| Palatine surface | |

| Mesial surface | |

| Distal surface | |

| Occlusal surface | |

| Carnassials | (know which teeth comprise the carnassials) |

| Hypsodont | |

| Brachydont | |

| Wolf teeth | Horse |

| Diastema = Interdental or interproximal space | |

| “Bars of mouth” | Horse |

| Infundibulum | |

| Galvayne’s groove | Horse |

| Dental star | Horse |

| Enamel spot | Horse |

| Dental pad | Ruminant |

| Tusks | Pig |

| Needle teeth | Pig |