2.3 Alkyl Groups

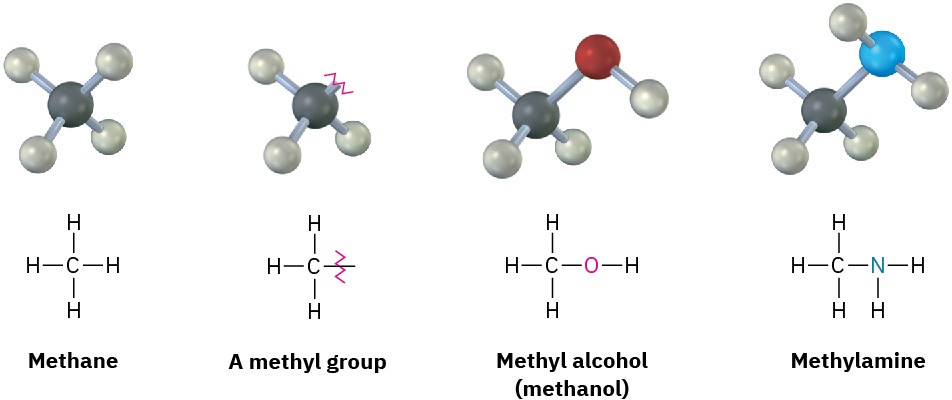

If you imagine removing a hydrogen atom from an alkane, the partial structure that remains is called an alkyl group. Alkyl groups are not stable compounds themselves, they are simply parts of larger compounds and are named by replacing the –ane ending of the parent alkane with an –yl ending. For example, removal of a hydrogen from methane, CH4, generates a methyl group, –CH3, and removal of a hydrogen from ethane, CH3CH3, generates an ethyl group, –CH2CH3. Similarly, removal of a hydrogen atom from the end carbon of any straight-chain alkane gives the series of straight-chain alkyl groups shown in Table 2.4. Combining an alkyl group with any of the functional groups listed earlier makes it possible to generate and name many thousands of compounds. For example:

Table 2.4 Some Straight-Chain Alkyl Groups

|

Alkane |

Name |

Alkyl group |

Name (abbreviation) |

|

CH4 |

Methane |

–CH3 |

Methyl (Me) |

|

CH3CH3 |

Ethane |

–CH2CH3 |

Ethyl (Et) |

|

CH3CH2CH3 |

Propane |

–CH2CH2CH3 |

Propyl (Pr) |

|

CH3CH2CH2CH3 |

Butane |

–CH2CH2CH2CH3 |

Butyl (Bu) |

|

CH3CH2CH2CH2CH3 |

Pentane |

–CH2CH2CH2CH2CH3 |

Pentyl |

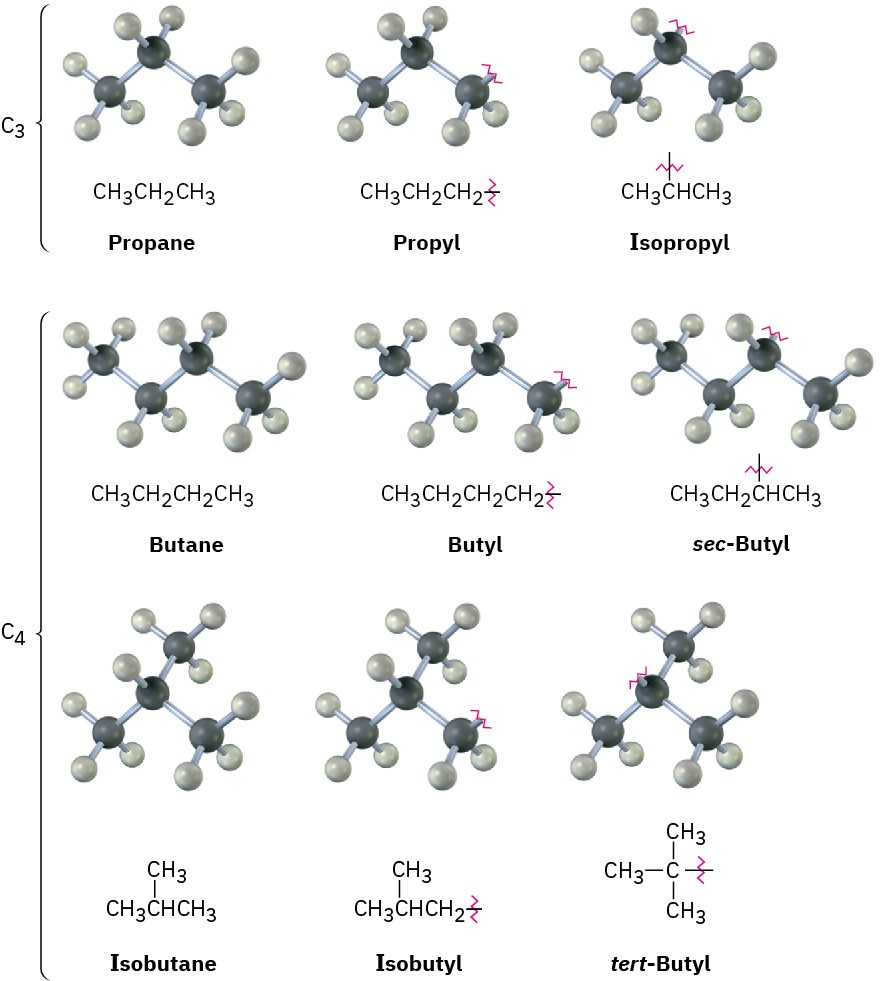

Just as straight-chain alkyl groups are generated by removing a hydrogen from an end carbon, branched alkyl groups are generated by removing a hydrogen atom from an internal carbon. Two 3-carbon alkyl groups and four 4-carbon alkyl groups are possible (Figure 2.5). Figure 2.5 Alkyl groups generated from straight-chain alkanes.

Figure 2.5 Alkyl groups generated from straight-chain alkanes.

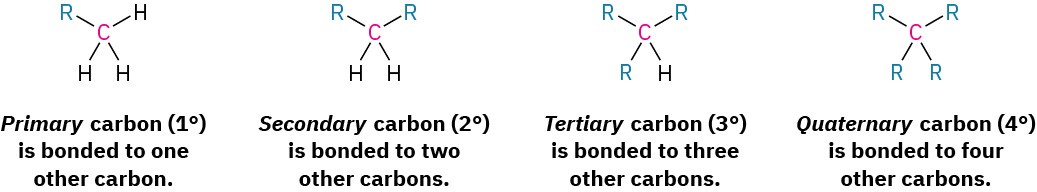

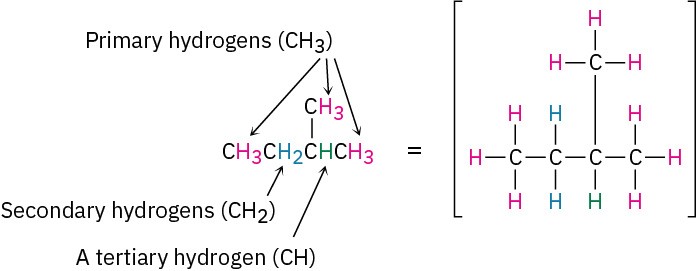

One further comment about naming alkyl groups: the prefixes sec– (for secondary) and tert– (for tertiary) used for the C4 alkyl groups in Figure 2.5 refer to the number of other carbon atoms attached to the branching carbon atom. There are four possibilities: primary (1°), secondary (2°), tertiary (3°), and quaternary (4°).

The symbol R is used here and throughout organic chemistry to represent a generalized organic group. The R group can be methyl, ethyl, propyl, or any of a multitude of others. You might think of R as representing the Rest of the molecule, which isn’t specified.

The symbol R is used here and throughout organic chemistry to represent a generalized organic group. The R group can be methyl, ethyl, propyl, or any of a multitude of others. You might think of R as representing the Rest of the molecule, which isn’t specified.

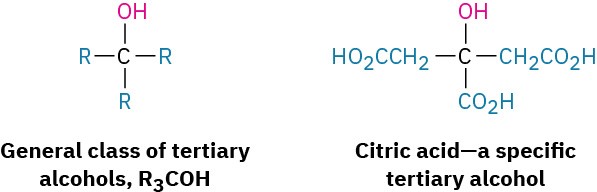

The terms primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary are routinely used in organic chemistry, and their meanings need to become second nature. For example, if we were to say, “Citric acid is a tertiary alcohol,” we would mean that it has an alcohol functional group (–OH) bonded to a carbon atom that is itself bonded to three other carbons.

In addition to speaking of carbon atoms as being primary, secondary, or tertiary, we speak of hydrogens in the same way. Primary hydrogen atoms are attached to primary carbons (RCH3), secondary hydrogens are attached to secondary carbons (R2CH2), and tertiary hydrogens are attached to tertiary carbons (R3CH). There is, however, no such thing as a quaternary hydrogen. (Why not?)

Problem 2.7

Problem 2.7

Draw the eight 5-carbon alkyl groups (pentyl isomers).

Problem 2.8

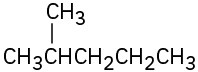

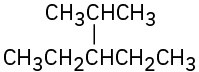

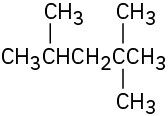

Identify the carbon atoms in the following molecules as primary, secondary, tertiary, or quaternary:

(a)

(b)

(c)

Problem 2.9

Identify the hydrogen atoms on the compounds shown in Problem 2.8 as primary, secondary, or tertiary.

Problem 2.10

Draw structures of alkanes that meet the following descriptions:

(a) An alkane with two tertiary carbons

(b) An alkane that contains an isopropyl group

(c) An alkane that has one quaternary and one secondary carbon