2 Why This Chapter?

Figure 2.1 The bristlecone pine is the oldest living organism on Earth. The waxy coating on its needles contains a mixture of organic compounds called alkanes, the subject of this chapter. (credit: modification of work “Gnarly Bristlecone Pine” by Rick Goldwaser/Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

The group of organic compounds called alkanes are simple and relatively unreactive, but they nevertheless provide a useful vehicle for introducing some important general ideas. In this chapter, we’ll use alkanes to introduce the basic approach to naming organic compounds and to take an initial look at some of the three-dimensional aspects of molecules, a topic of particular importance in understanding biological organic chemistry.

According to Chemical Abstracts, the publication that abstracts and indexes the chemical literature, there are more than 195 million known organic compounds. Each of these compounds has its own physical properties, such as melting point and boiling point, and each has its own chemical reactivity.

Chemists have learned through years of experience that organic compounds can be classified into families according to their structural features and that the members of a given family have similar chemical behavior. Instead of 195 million compounds with random reactivity, there are a few dozen families of organic compounds whose chemistry is reasonably predictable. We’ll study the chemistry of specific families throughout much of this book, beginning in this chapter with a look at the simplest family, the alkanes.

Figure 2.2 The musk gland of the male Himalayan musk deer secretes a substance once used in perfumery that contains cycloalkanes of 14 to 18 carbons. (credit: modification of work “Siberian musk deer in the tiaga” by ErikAdamsson/Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0)

We’ll see numerous instances in future chapters where the chemistry of a given functional group is affected by being in a ring rather than an open chain. Because cyclic molecules are encountered in most pharmaceuticals and in all classes of biomolecules, including proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids, it’s important to understand the behavior of cyclic structures.

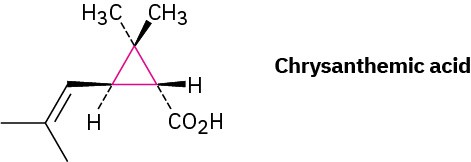

Although we’ve only discussed open-chain compounds up to now, most organic compounds contain rings of carbon atoms. Chrysanthemic acid, for instance, whose esters occur naturally as the active insecticidal constituents of chrysanthemum flowers, contains a three-membered (cyclopropane) ring.

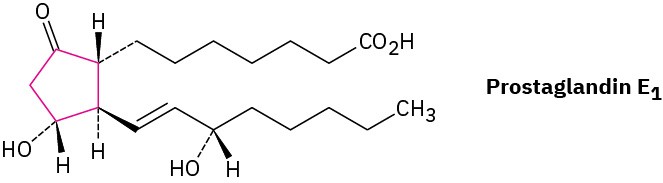

Prostaglandins, potent hormones that control an extraordinary variety of physiological functions in humans, contain a five-membered (cyclopentane) ring.

Prostaglandins, potent hormones that control an extraordinary variety of physiological functions in humans, contain a five-membered (cyclopentane) ring.

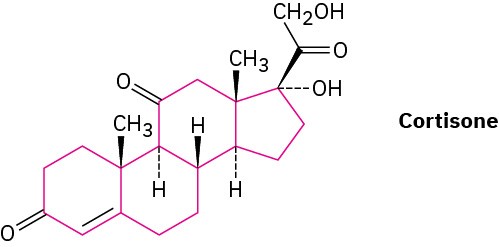

Steroids, such as cortisone, contain four rings joined together—three six-membered (cyclohexane) and one five-membered.

Steroids, such as cortisone, contain four rings joined together—three six-membered (cyclohexane) and one five-membered.