Creativity and design thinking are essential tools for entrepreneurs navigating uncertainty and solving real problems. By focusing on empathy, experimentation, and iteration, design thinking helps transform ideas into practical, user-centered solutions. Creativity isn’t just inspiration—it’s a skill that can be developed. When applied intentionally, these approaches help entrepreneurs build innovative, adaptable, and impactful ventures.

Chapter 5 – Creativity & Design Thinking

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between creativity, innovation, and invention

- Define the steps in the Creative Process

- Describe the three types of problem solvers

- Identify the 5 stages of Design Thinking

Creativity, Innovation, and Invention

One of the key requirements for entrepreneurial success is your ability to develop and offer something unique to the marketplace. Over time, entrepreneurship has become associated with creativity, the ability to develop something original, particularly an idea or a representation of an idea. Innovation requires creativity, but innovation is more specifically the application of creativity. Innovation is the manifestation of creativity into a usable product or service. How is an invention different from an innovation? All inventions contain innovations, but not every innovation rises to the level of a unique invention. For our purposes, an invention is a truly novel product, service, or process. It is such a leap that it is not considered an addition to or a variant of an existing product but something unique. The table below highlights the differences between these three concepts.

| Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| Creativity | ability to develop something original, particularly an idea or a representation of an idea |

| Innovation | change that adds value to an existing product or service |

| Invention | truly novel product, service, or process that, though based on ideas and products that have come before, represents a leap, a creation truly novel and different |

Creativity, innovation, inventiveness, and entrepreneurship can be tightly linked. It is possible for one person to model all these traits to some degree. Additionally, you can develop your creativity skills, sense of innovation, and inventiveness in a variety of ways. In this section, we’ll discuss each of the key terms and how they relate to the entrepreneurial spirit.

Creativity

Entrepreneurial creativity and artistic creativity are not so different. You can find inspiration in your favorite books, songs, and paintings, and you also can take inspiration from existing products and services. You can find creative inspiration in nature, in conversations with other creative minds, and through formal ideation exercises, for example, brainstorming. Ideation is the purposeful process of opening up your mind to new trains of thought that branch out in all directions from a stated purpose or problem. Brainstorming, the generation of ideas in an environment free of judgment or dissension with the goal of creating solutions, is just one of dozens of methods for coming up with new ideas.

You can benefit from setting aside time for ideation. Reserving time to let your mind roam freely as you think about an issue or problem from multiple directions is a necessary component of the process. Ideation takes time and a deliberate effort to move beyond your habitual thought patterns. If you consciously set aside time for creativity, you will broaden your mental horizons and allow yourself to change and grow.

Entrepreneurs work with two types of thinking. Linear thinking—sometimes called vertical thinking—involves a logical, step-by-step process. In contrast, creative thinking is more often lateral thinking, free and open thinking in which established patterns of logical thought are purposefully ignored or even challenged. If you can ignore logic; anything becomes possible. Linear thinking is crucial in turning your idea into a business. Lateral thinking will allow you to use your creativity to solve problems that arise.

It is certainly possible for you to be an entrepreneur and focus on linear thinking. Many viable business ventures flow logically and directly from existing products and services. However, for various reasons, creativity and lateral thinking are emphasized in many contemporary contexts in the study of entrepreneurship. Some reasons for this are increased global competition, the speed of technological change, and the complexity of trade and communication systems. These factors help explain not just why creativity is emphasized in entrepreneurial circles but also why creativity should be emphasized. Product developers of the twenty-first century are expected to do more than simply push products and innovations a step further down a planned path. Newer generations of entrepreneurs are expected to be path breakers in new products, services, and processes.

Examples of creativity are all around us. They come in the forms of fine art and writing, or in graffiti and viral videos, or in new products, services, ideas, and processes. In practice, creativity is incredibly broad. It is all around us whenever or wherever people strive to solve a problem, large or small, practical or impractical.

Innovation

We previously defined innovation as a change that adds value to an existing product or service. According to the management thinker and author Peter Drucker, the key point about innovation is that it is a response to both changes within markets and changes from outside markets. For Drucker, classical entrepreneurship psychology highlights the purposeful nature of innovation. Business firms and other organizations can plan to innovate by applying either lateral or linear thinking methods, or both. In other words, not all innovation is purely creative. If a firm wishes to innovate a current product, what will likely matter more to that firm is the success of the innovation rather than the level of creativity involved.

One innovation that demonstrates innovative thinking is the use of cashier kiosks in fast-food restaurants. McDonald’s was one of the first to launch these self-serve kiosks. Historically, the company has focused on operational efficiencies (doing more/better with less). In response to changes in the market, changes in demographics, and process need, McDonald’s incorporated self-serve cashier stations into their stores. These kiosks address the need of younger generations to interact more with technology and gives customers faster service in most cases.

Disruptive innovation is a process that significantly affects the market by making a product or service more affordable and/or accessible, so that it will be available to a much larger audience. Clay Christensen of Harvard University coined this term in the 1990s to emphasize the process nature of innovation. For Christensen, the innovative component is not the actual product or service, but the process that makes that product more available to a larger population of users. He has since published a good deal on the topic of disruptive innovation, focusing on small players in a market. Christensen theorizes that a disruptive innovation from a smaller company can threaten an existing larger business by offering the market new and improved solutions. The smaller company causes the disruption when it captures some of the market share from the larger organization. One example of a disruptive innovation is Uber and its impact on the taxicab industry. Uber’s innovative service, which targets customers who might otherwise take a cab, has shaped the industry as whole by offering an alternative that some deem superior to the typical cab ride.

One key to innovation within a given market space is to look for pain points, particularly in existing products that fail to work as well as users expect them to. A pain point is a problem that people have with a product or service that might be addressed by creating a modified version that solves the problem more efficiently. For example, you might be interested in whether a local retail store carries a specific item without actually going there to check. Most retailers now have a feature on their websites that allows you to determine whether the product (and often how many units) is available at a specific store. This eliminates the need to go to the location only to find that they are out of your favorite product. Once a pain point is identified in a firm’s own product or in a competitor’s product, the firm can bring creativity to bear in finding and testing solutions that sidestep or eliminate the pain, making the innovation marketable. This is one example of an incremental innovation, an innovation that modifies an existing product or service.

Invention

An invention is a leap in capability beyond innovation. Some inventions combine several innovations into something new. Invention certainly requires creativity, but it goes beyond coming up with new ideas, combinations of thought, or variations on a theme. Inventors build. Developing something users and customers view as an invention could be important to some entrepreneurs, because when a new product or service is viewed as unique, it can create new markets. True inventiveness is often recognized in the marketplace, and it can help build a valuable reputation and help establish market position if the company can build a future-oriented corporate narrative around the invention.

Besides establishing a new market position, a true invention can have a social and cultural impact. At the social level, a new invention can influence the ways institutions work. For example, the invention of desktop computing put accounting and word processing into the hands of nearly every office worker. The ripple effects spread to the school systems that educate and train the corporate workforce. Not long after the spread of desktop computing, workers were expected to draft reports, run financial projections, and make appealing presentations. Specializations or aspects of specialized jobs—such as typist, bookkeeper, corporate copywriter—became necessary for almost everyone headed for corporate work. Colleges and eventually high schools saw software training as essential for students of almost all skill levels. These additional capabilities added profitability and efficiencies, but they also have increased job requirements for the average professional.

The Creative Process: The Five Stages of Creativity

The previous section defined creativity, innovation, and invention, and provided examples. You might think of creativity as raw ideas; innovation as transforming creativity into a functional purpose, often meant to eradicate a pain point or to fulfill a need; and invention as a creation that leaves a lasting impact. In this section, you will learn about processes designed to help you apply knowledge from the previous section.

Raw creativity and an affinity for lateral thinking may be innate, but creative people must refine these skills in order to become masters in their respective fields. They practice in order to apply their skills readily and consistently, and to integrate them with other thought processes and emotions. Anyone can improve in creative efforts with practice. For our purposes, the creative process is a model for applied creativity that is derived from an entrepreneurial approach. It requires:

- Preparation

- Incubation

- Insight

- Evaluation

- Elaboration

Preparation

Preparation involves investigating a chosen field of interest, opening your mind, and becoming immersed in materials, mindset, and meaning. If you have ever tried to produce something creative without first absorbing relevant information and observing skilled practitioners at work, then you understand how difficult it is. This base of knowledge and experience mixed with an ability to integrate new thoughts and practices can help you sift through the ideas quicker. However, relying too heavily on prior knowledge can restrict the creative process. When you immerse yourself in a creative practice, you make use of the products or the materials of others’ creativity. For example, a video-game designer plays different types of video games on different consoles, computers, and online in networks. They may play alone, with friends in collaboration, or in competition. Consuming the products in a field gives you a sense of what is possible and indicates boundaries that you may attempt to push with your own creative work. Preparation broadens your mind and lets you study the products, practice, and culture in a field. It is also a time for goal setting. Whether your chosen field is directly related to art and design, such as publishing, or involves human-centric design, which includes all sorts of software and product design efforts, you need a period of open-minded reception to ideas. Repetitive practice is also part of the preparation stage, so that you can understand the current field of production and become aware of best practices, whether or not you are currently capable of matching them. During the preparation stage, you can begin to see how other creative people put meaning into their products, and you can establish benchmarks against which to measure your own creative work.

Incubation

Incubation refers to giving yourself, and your subconscious mind in particular, time to incorporate what you learned and practiced in the preparation stage. Incubation involves the absence of practice. It may look to an outsider as though you are at rest, but your mind is at work. A change of environment is key to incubating ideas. A new environment allows you to receive stimuli other than those directly associated with the creative problem you are working on. It could be as simple as taking a walk or going to a new coffee shop to allow your mind to wander and take in the information you gathered in the previous stage. Mozart stated, “When I am, as it were, completely myself, entirely alone, and of good cheer—say, traveling in a carriage, or walking after a good meal, or during the night when I cannot sleep; it is on such occasions that my ideas flow best and most abundantly.” Incubation allows your mind to integrate your creative problem with your stored memories and with other thoughts or emotions you might have. This simply is not possible to do when you are consciously fixated on the creative problem and related tasks and practice.

Incubation can take a short or a long time, and you can perform other activities while allowing this process to take place. One theory about incubation is that it takes language out of the thought process. If you are not working to apply words to your creative problems and interests, you can free your mind to make associations that go deeper, so to speak, than language. Patiently waiting for incubation to work is quite difficult. Many creative and innovative people develop hobbies involving physical activity to keep their minds busy while they allow ideas to incubate.

Insight

Insight or “illumination” is a term for the “aha!” moment—when the solution to a creative problem suddenly becomes readily accessible to your conscious mind. The “aha!” moment has been observed in literature, in history, and in cognitive studies of creativity. Insights may come all at once or in increments. They are not easily understood because, by their very nature, they are difficult to isolate in research and experimental settings. For the creative entrepreneur, however, insights are a delight. An insight is the fleeting time when your preparation, practice, and period of incubation coalesce into a stroke of genius. Whether the illumination is the solution to a seemingly impossible problem or the creation of a particularly clever melody or turn of phrase, creative people often consider it a highlight in their lives. For an entrepreneur, an insight holds the promise of success and the potential to help massive numbers of people overcome a pain point or problem. Not every insight will have a global impact, but coming up with a solution that your subconscious mind has been working on for some time is a real joy.

Evaluation

Evaluation is the purposeful examination of ideas. You will want to compare your insights with the products and ideas you encountered during preparation. You also will want to compare your ideas and product prototypes to the goals you set out for yourself during the preparation phase. Creative professionals will often invite others to critique their work at this stage. Because evaluation is specific to the expectations, best practices, and existing product leaders in each field, evaluation can take on many forms. You are looking for assurance that your standards for evaluation are appropriate. Judge yourself fairly, even as you apply strict criteria and the well-developed sense of taste you acquired during the preparation phase. For example, you might choose to interview a few customers in your target demographics for your product or service. The primary objective is to understand the customer perspective and the extent to which your idea aligns with their position.

Elaboration

The last stage in the creative process is elaboration, that is, actual production. Elaboration can involve the release of a minimum viable product (MVP). This version of your invention may not be polished or complete, but it should function well enough that you can begin to market it while still elaborating on it in an iterative development process. Elaboration also can involve the development and launch of a prototype, the release of a software beta, or the production of some piece of artistic work for sale. Many consumer-product companies, such as Johnson & Johnson or Procter & Gamble, will establish a small test market to garner feedback and evaluations of new products from actual customers. These insights can give the company valuable information that can help make the product or service as successful as possible.

At this stage what matters most in the entrepreneurial creative process is that the work becomes available to the public so that they have a chance to adopt it.

Creative Problem Solving

Innovative entrepreneurs are essentially problem solvers, but this level of innovation—identifying a pain point and working to overcome it—is only one in a series of innovative steps. In the influential business publication Forbes, the entrepreneur Larry Myler notes that problem solving is inherently reactive. That is, you have to wait for a problem to happen in order to recognize the need to solve the problem. Solving problems is an important part of the practice of innovation, but to elevate the practice and the field, innovators should anticipate problems and strive to prevent them. In many cases, they create systems for continuous improvement, which Myler notes may involve “breaking” previous systems that seem to function perfectly well. Striving for continuous improvement helps innovators stay ahead of market changes. Thus, they have products ready for emerging markets, rather than developing projects that chase change, which can occur constantly in some tech-driven fields. One issue with building a system for constant improvement is that you are in essence creating problems in order to solve them, which goes against established culture in many firms. Innovators look for organizations that can handle purposeful innovation, or they attempt to start them. Some innovators even have the goal of innovating far ahead into the future, beyond current capacities. In order to do this, Myler suggests bringing people of disparate experiential backgrounds with different expertise together. These relationships are not guarantees of successful innovation, but such groups can generate ideas independent of institutional inertia. Thus, innovators are problem solvers but also can work with forms of problem creation and problem imagination. They tackle problems that have yet to exist in order to solve them ahead of time.

Types of Problem Solvers

Entrepreneurs have an insatiable appetite for problem solving. This drive motivates them to find a resolution when a gap in a product or service occurs. They recognize opportunities and take advantage of them. There are several types of entrepreneurial problem solvers, including self-regulators, theorists, and petitioners.

Self-Regulating Problem Solvers

Self-regulating problem solvers are autonomous and work on their own without external influence. They have the ability to see a problem, visualize a possible solution to the problem, and seek to devise a solution, as the figure below illustrates. The solution may be a risk, but a self-regulating problem solver will recognize, evaluate, and mitigate the risk. For example, an entrepreneur has programmed a computerized process for a client, but in testing it, finds the program continually falls into a loop, meaning it gets stuck in a cycle and doesn’t progress. Rather than wait for the client to find the problem, the entrepreneur searches the code for the error causing the loop, immediately edits it, and delivers the corrected program to the customer. There is immediate analysis, immediate correction, and immediate implementation. The self-regulating problem solvers’ biggest competitive advantage is the speed with which they recognize and provide solutions to problems.

Theorist Problem Solvers

Theorist problem solvers see a problem and begin to consider a path toward solving the problem using a theory. Theorist problem solvers are process oriented and systematic. While managers may start with a problem and focus on an outcome with little consideration of a means to an end, entrepreneurs may see a problem and begin to build a path with what is known, a theory, toward an outcome. That is, the entrepreneur proceeds through the steps to solve the problem and then builds on the successes, rejects the failures, and works toward the outcome by experimenting and building on known results. At this point, the problem solver may not know the outcome, but a solution will arise as experiments toward a solution occur. The figure below shows this process.

For example, if we consider Marie Curie as an entrepreneur, Curie worked toward the isolation of an element. As different approaches to isolating the element failed, Curie recorded the failures and attempted other possible solutions. Curie’s failed theories eventually revealed the outcome for the isolation of radium. Like Curie, theorists use considered analysis, considered corrective action, and a considered implementation process. When time is of the essence, entrepreneurs should understand continual experimentation slows the problem-solving process.

Petitioner Problem Solvers

Petitioner problem solvers (see figure below) see a problem and ask others for solution ideas. This entrepreneur likes to consult a person who has “been there and done that.” The petitioner might also prefer to solve the problem in a team environment. Petitioning the entrepreneurial team for input ensures that the entrepreneur is on a consensus-driven path. This type of problem solving takes the longest to complete because the entrepreneur must engage in a democratic process that allows all members on the team to have input. The process involves exploration of alternatives for the ultimate solution. In organizational decision-making, for example, comprehensiveness is a measure of the extent a firm attempts to be inclusive or exhaustive in its decision-making. Comprehensiveness can be gauged by the number of scheduled meetings, the process by which information is sought, the process by which input is obtained from external sources, the number of employees involved, the use of specialized consultants and the functional expertise of the people involved, the years of historical data review, and the assignment of primary responsibility, among other factors. Comprehensive decision-making would be an example of a petitioner problem-solving style, as it seeks input from a vast number of team members.

In summary, there is no right or wrong style of problem solving; each problem solver must rely on the instincts that best drive innovation. Further, they must remember that not all problem-solving methods work in every situation. They must be willing to adapt their own preference to the situation to maximize efficiency and ensure they find an effective solution. Attempting to force a problem-solving style may prevent an organization from finding the best solution. While general entrepreneurial problem-solving skills such as critical thinking, decisiveness, communication, and the ability to analyze data will likely be used on a regular basis in your life and entrepreneurial journey, other problem-solving skills and the approach you take will depend on the problem as it arises.

Design Thinking

David Kelley, founder of Stanford University’s Design School and cofounder of design company IDEO, is credited as the originator of design thinking, at least within business and entrepreneurial contexts. IDEO grew from a merger of the creator of Apple’s first mouse and the first laptop computer designer, David Kelley Design and ID Two, respectively. Almost a decade after the 1982 Apple creations, the 1991-merged company primarily focused on the traditional design of products, ranging from toothbrushes to chairs. Yet another decade later, the company found itself designing consumer experiences more so than consumer products. Kelley began using the word “thinking” to describe the design process involved in creating customer experiences rather than creating physical products. The term design thinking was born. Design thinking is a method to focus the design and development decisions of a product on the needs of the customer, typically involving an empathy-driven process to define complex problems and create solutions that address those problems.

A common core of design thinking is its application beyond the design studio, as the methods and tools have been articulated for use by those outside of the field, particularly business managers. Design practice is now being applied beyond product and graphic areas to the design of digital interactions, services, business strategy, and social policy.

Human-Centered Design Thinking

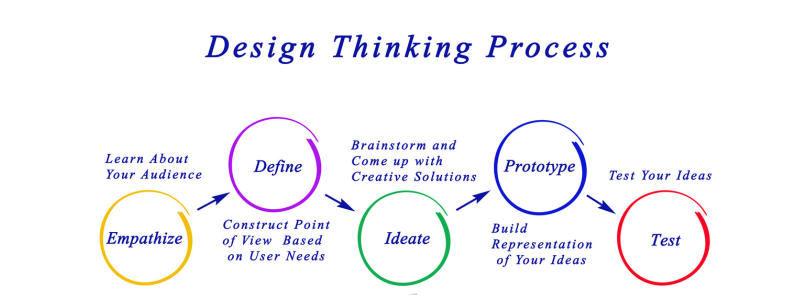

One design thinking approach that is taught at places like Stanford’s Design School and organizations like the LUMA Institute (a global company that teaches people how to be innovative) is human-centered design (HCD). HCD, as the name suggests, focuses on people during design and development. Inspiration for ideas comes from exploration of actual people, their needs and problems. HCD emphasizes the following spaces of the design thinking process:

- Empathizing: As illustrated by the human-centered approach, it is important to have empathy for the problem you are attempting to solve.

- Defining: This aspect involves describing the core problem(s) that you and your team have identified. Asking “how might we?” questions helps narrow the focus, as the ultimate aim here is to identify a problem statement that illustrates the problem you want to tackle.

- Ideating: This is where you begin to come up with ideas that address the problem “space” you have defined.

- Prototyping: In this space, the entrepreneur creates and tests inexpensive, scaled-down versions of a product with features or benefits that serve as solutions for previously identified problems. This could be tested internally among employees or externally with potential customers. This is an experimental phase.

- Testing: Designers apply rigorous tests of the complete product using the best solutions identified in the prototyping space.

Link to Learning: Ideation Technique

Ideation is the process of generating ideas and solutions through various techniques such as brainstorming and sketching sessions. There are hundreds of ideation techniques available. Design thinking incorporates experience-based insights, judgments, and intuition from the end users’ perspectives, while in a rational analytic approach, the solution process often becomes formalized into a set of rules.

If your group is interested in IDEO U’s Mash-Up Activity, you can learn more here.

Project Focus

What ideation exercises have you done in the past that have been successful? How can you use ideation in your project?

Attribution

This work builds upon materials originally developed by OpenStax in their publication “Entrepreneurship,” which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

definition

the process of generating ideas and solutions through various techniques such as brainstorming and sketching sessions