Chemistry Matters — Photolithography

Fifty years ago, someone interested in owning a computer would have paid approximately

$150,000 for 16 megabytes of random-access memory that would have occupied a volume the size of a small desk. Today, anyone can buy 60 times as much computer memory for

$10 and fit the small chip into their shirt pocket. The difference between then and now is due to improvements in photolithography, the process by which integrated-circuit chips are made.

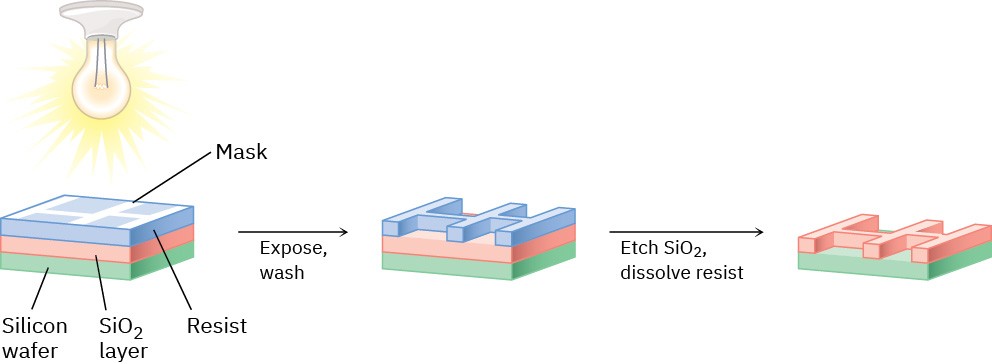

Photolithography begins by coating a layer of SiO2 onto a silicon wafer and further coating with a thin (0.5–1.0 μm) film of a light-sensitive organic polymer called a resist. A mask is then used to cover those parts of the chip that will become a circuit, and the wafer is irradiated with UV light. The nonmasked sections of the polymer undergo a chemical change when irradiated, which makes them more soluble than the masked, unirradiated sections. On washing the irradiated chip with solvent, solubilized polymer is selectively removed from the irradiated areas, exposing the SiO2 underneath. This SiO2 is then chemically etched away by reaction with hydrofluoric acid, leaving behind a pattern of polymer-coated SiO2. Further washing removes the remaining polymer, leaving a positive image of the mask in the form of exposed ridges of SiO2 (Figure 14.16). Additional cycles of coating, masking, and etching then produce the completed chips.

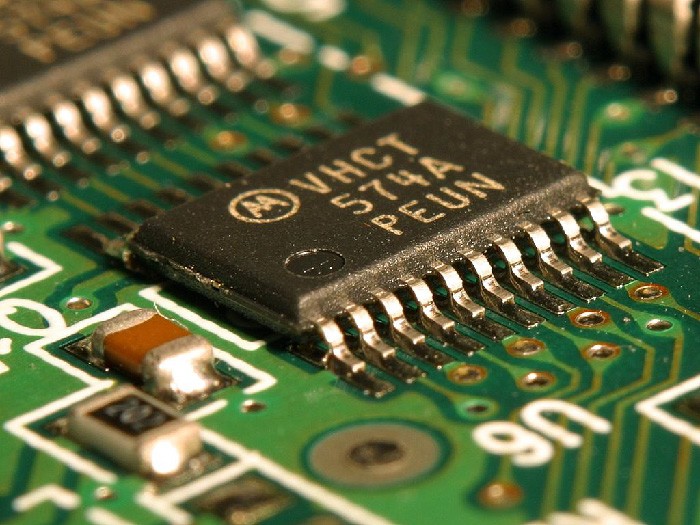

Figure 14.15 Manufacturing the ultrathin circuitry on this computer chip depends on the organic chemical reactions of special polymers. (credit: “Integrated circuit on microchip” by Jon Sullivan/Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Figure 14.16 Outline of the photolithography process for producing integrated circuit chips.

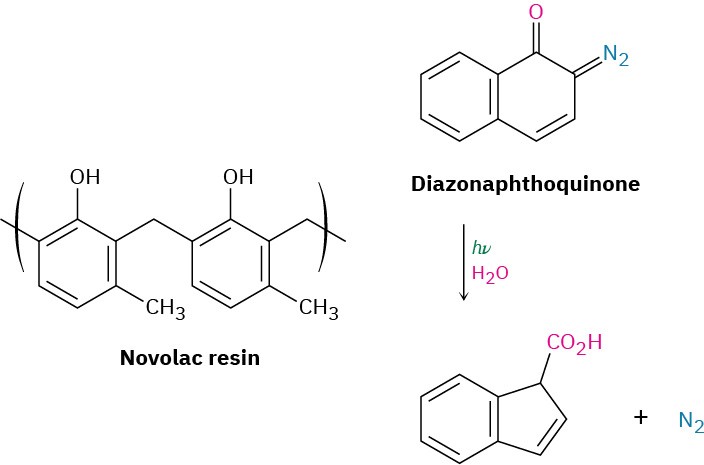

The polymer resist currently used in chip manufacturing is based on the two-component diazoquinone–novolac system. Novolac resin is a soft, relatively low-molecular-weight polymer made from methylphenol and formaldehyde, while the diazoquinone is a bicyclic (two-ring) molecule containing a diazo group =N=N) adjacent to a ketone carbonyl (C=O). The diazoquinone–novolac mix is relatively insoluble when fresh, but on exposure to ultraviolet light and water vapor, the diazoquinone component undergoes reaction to yield N2 and a carboxylic acid, which can be washed away with dilute base. Novolac– diazoquinone technology is capable of producing features as small as 0.5 μm (5 × 10–7 m), but further improvements in miniaturization are still being developed.